This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

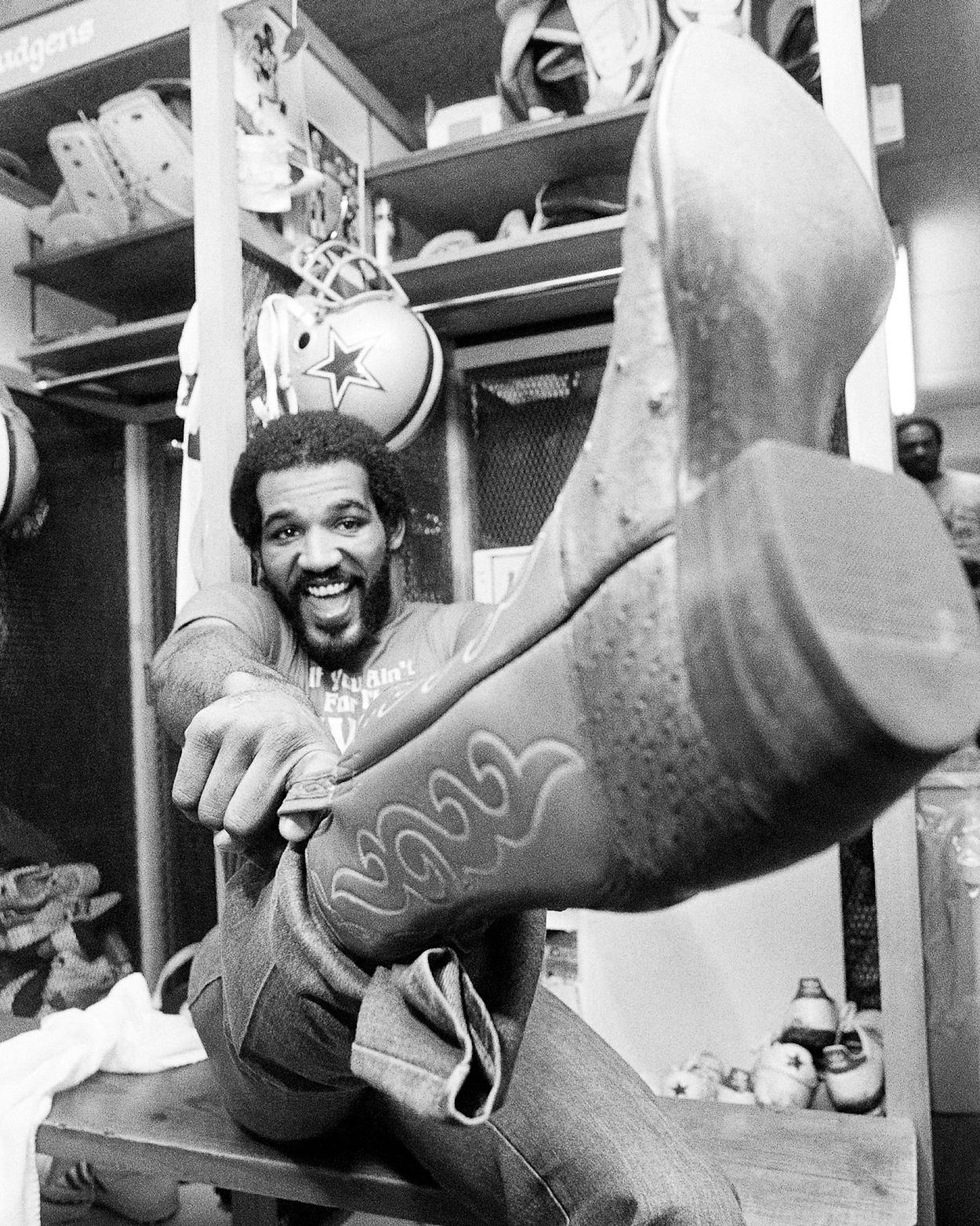

Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson played linebacker in three Super Bowls for the Dallas Cowboys in the late seventies. After cocaine addiction and a neck injury cut short his football career, Henderson was arrested in 1983 and charged with sexual battery. He served two years and three months in California prisons before his release in 1986. The following episodes are taken from his book, Out of Control, written with Peter Knobler and published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons this month.

1975: Making the Cut

I saw Tom Landry show real emotion one time only. It was the last week of training camp, 1975, time for the final cuts. Some guys were going to make this team and others weren’t, and the decision was Coach Landry’s. We still had about fifteen rookies in camp, and somebody had to go.

Ken Hutcherson was a hard-hitting, jovial, fun-loving middle linebacker. Everybody liked him. Hutcherson was a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, led the Cowboy player chapel services, and was always trying to convert people to Christianity. He was dark black, a good man, and Tom Landry loved him.

The coaches played Hutcherson in all the preseason games, gave him every opportunity in the world to come through and make the team. He had a hard time, looked pretty bad in the games. I felt sorry watching his performances. He seemed to be knocked up in the air a whole lot, stumbled several times, missed tackles. He just didn’t do all the things you needed to do to make the team.

The morning of the final cut Landry pulled a sheet of paper off his clipboard and said, “Here are the rookies who made the team: Randy White, Thomas Henderson, Burton Lawless, Randy Hughes, Rollie Woolsey, Scott Laidlaw, Percy Howard, Mitch Hoopes, Bob Breunig, Herb Scott, Pat Donovan, Kyle Davis.”

He looked up from his list. “This is the toughest part of this business,” he said slowly. “This is the only part of this business I don’t really like very much. Today I had to make a decision. I had to cut a fine young man, a good friend, a good Christian. I had to let Ken Hutcherson go.” And the man began to cry.

Everybody was going Whoa! Even Lee Roy Jordan, who had been around for more than a decade, hadn’t seen Coach Landry do that. I’d never heard him describe anyone as a decent human being let alone a good friend.

Randy White, Bob Breunig, and I were standing in the corridor that led out to the practice field that afternoon when the coach walked by. He looked at us and squinted. “I hope you all were worth it.”

1977: Making It

Ladies around the country find ways of getting to professional athletes, and I was easy to find, didn’t have to ask me twice.

One night I was in the Fairmont Hotel in downtown Dallas with one of the most beautiful women I’d ever met. Blond, leggy, smooth, the kind of girl that five years before I would have been killed for talking to. My room was like a palace: black marble Jacuzzi, gold handles on the fixtures, gold towel racks, three-inch-thick carpet. We’d had Dom Pérignon and caviar and a candle-lit room-service dinner and the mood was just right.

I was sitting there with her in the Jacuzzi, talking to her. We were doing cocaine, snorting lines from a neat little mirror through a gold straw, smoking some primo marijuana, and I was really getting into talking to her. She was so beautiful I didn’t want to just jump into the sack with her, I wanted to savor the moment, just kind of relax and let this bath last forever.

“You know, baby,” I said as the water gurgled around us, “I really want to please you. Whatever you want, I want you to have.” I was soothed just saying the words, my muscles untightening, my whole body unwinding. “Pleasing you, turning you on, is what turns me on. Just tell me what you want—whatever you want—and I’ll do my best to give it to you.”

This beautiful woman stretched out in the bath, and I was in long-leg heaven. She smiled as she turned to me.

“I want Tony Dorsett.”

1979: Snorting at the Super Bowl

By the third quarter I needed something. NFL uniforms have two little pockets where you can hide stuff, one right behind your knee pads and the other up around your waist. I had tucked my inhaler in the higher one; I didn’t need a little bottle digging into my knees when I hit the ground, and I sure as hell didn’t want anyone fishing in there if I got an injury.

Everybody knew I had sinus problems. I was carrying around a roll of toilet paper at team meetings and sniffling like I was living in the snow, so it wasn’t going to cause any talk if I pulled out my inhaler and gave myself some drops. I walked to the side while we were on offense and took a couple of deep belts of my liquid cocaine. My nose was getting raw from all the hits on the field, and the Miami humidity was making even simple things like breathing pretty hard, so I just wanted to anesthetize it once more, open things up. I took another couple of jolts. I wasn’t doing it to get high—I was on full alert as it was—I just needed to keep the pain off of me. My teammates would have known what I was doing if they’d been watching, but they had the Super Bowl to think about.

1979: Superstars

Next stop, the Superstars competition. That year it was held in Freeport, the Bahamas. I packed for the festivities and carried it on with me: a half-ounce of cocaine, an ounce of incredible Thai sticks, and about thirty Quaaludes, each different high in its own plastic bag.

I’d been on the plane taking a toot here and there, so when I got to customs I was loose. When they asked for my shoulder bag I gave it to them without hesitation. Then I realized what I’d done. “Oh, my God,” I said to myself. “I’m busted. This is it, I’m going to jail, my life is over.”

This jet-black gentleman, obviously 150 percent Bahamian, was the customs agent, and he was pawing through the bag like a pro. He opened the sides and slid his fingers down where I would have been hiding stuff if I’d been hiding it. The baggies were sitting out in the middle of my satchel like letters from home. He looked at them. I saw him run his fingers over the packages. I looked him in the eyes.

“Hollywood,” he said in his British Bahamian lilt, “have a good time. I see you have brought everything you might need.”

I’m a star! They don’t bust stars! I was invulnerable.

1979: The Terrible Towel

The Redskins were up for us. I had called them turkeys the year before, and it was the first time I had seen them since. It was not a good game. I was overpowered, I got used by the tight end. I couldn’t make any moves, he was all over me. I don’t think I made a single tackle the entire game.

During the second half I picked a towel up and waved it in front of the lens and said, “Cowboys Number One!” No big deal. Up in the press box my coach Jerry Tubbs saw it. We were losing—we finally lost the game 34–20—and he objected.

In the locker room afterward Coach Tubbs approached me, and I had never seen him this mad. “What are you doing on the sidelines mugging for the camera when we’re losing the game?” Real fast and agitated. “You know what, Thomas? If I was the coach, I’d cut you today. I swear to God I would. I can’t believe you and how inconsiderate you are of this team!” He rushed on.

“Get the f— away from me!” I made a move like I was going to bust him over the head with the helmet that was in my hand.

On the flight home I got wasted. I took a Quaalude after the game, snorted a noseful of coke in the lavatory, and I started talking loud. “Trade me, I don’t give a f— about this.”

About seven-thirty in the morning the phone rang. It was Marge Kelly, Landry’s secretary. “Thomas,” she said, “Coach Landry wants to see you this morning.” I yawned. “Can I see him after practice?” “No,” she answered, “I think you better see him before practice.”

The whole Cowboys office was empty, all the doors were closed. There could have been sagebrush kicking down the corridors, like it was cleared for a gunfight. I walked straight into Landry’s office. The coach took his glasses off, got up, walked over, and closed the door.

“Thomas,” he began, “we had a deal this year. You did pretty good, up to a point. I don’t know what’s wrong with you. You have shown great disrespect to the staff, you’ve been a disruptive influence on my team, and your behavior in Washington last night is unforgivable.

“You can play football for somebody else. I just can’t handle you anymore. I’m putting you on waivers.”

“No, no, no,” I told him, arrogant and confident and rushing. “You ain’t going to put me on shit. You can’t fire me, ’cause you know what I’m going to do? I quit. I’m retiring as of this moment.”

1980: The Ultimate High

The Houston Oilers needed a linebacker. I called their head coach, Bum Phillips. Football was what I did, who I was. I wanted to play.

If first impressions are everlasting, when I walked into the Houston Oiler practice facility I felt like I’d joined a second-class organization. The lockers were wood and old chicken-coop wire, and they were dirty. There just didn’t seem to be the care and attention to detail the Cowboys had defined as professionalism.

It didn’t take long for me to run down my cocaine connections. Several Oilers were freebasing—they got busted a couple of years later—and I got introduced to this guy named Travis. He had a pipe going. “Give me a hit of that,” I said.

There comes a time in all addicts’ lives when they take the hit that pushes them over the line. This was mine. I took the pipe, and it took me. It changed my life.

First thing it did was go right through me. I went straight to the bathroom. When I got back out my ears were ringing, my breath was short, my heart was racing, my pulse was too much over too much. I was wired. And I wanted to hit it again. And I kept hitting it.

Some people search for enlightenment, some search for the truth. My search was for the ultimate high, and I had found it. It had a kind of hum to it, a harmony, like your whole body comes alive, or dies, I’m not sure which. You can take a hit and maintain that level for a long while, but when it fades you’ve got to get back there.

I wouldn’t have left if I hadn’t had to go to work. I was late to the 10 o’clock meeting. I got out of practice at 11:45 and ran right back over to Travis’.

1980: Paranoia

I was an animal. The obsession with freebasing took me by storm. While the Houston Oilers were playing Tampa Bay and the Bengals, the Broncos, Patriots, Bears, Jets and Browns, I was madly stalking Houston full of freebase. I would barely make my physical therapy and ice-down sessions for my leg in the morning, then fall over by Travis’ and base out. I would go home after freebasing and not seeing my wife for five days, and I’d accuse her of cheating on me. I’d grab bags of garbage from the trash and pull them inside and throw them on the floor: “Who drank this? Who ate this? Who are you messing with?” Total paranoia. Finally I moved out on her and got a room at the Marriott. That was my home. That and Travis’.

I was completely gone. Whatever there was of Thomas Henderson had been destroyed, and in its place was this madman.

Late one hot, humid night I was standing by the window of my room at the Marriott smoking the shit, when I was sure that I saw policemen in the parking lot. They were after me. They were going to bust me. I packed up all my stuff—my cocaine, my pipe, my lighter—put on my full-length fur coat, don’t ask me why, and walked out of the hotel. I needed to go somewhere safe.

The Marriott was about fifteen blocks from the Astrodome. I would be safe at the Astrodome; it was the one place where I would probably get a break.

Clutching my freebase tools, the bag of coke rocks in my hand, I walked the fifteen blocks. The paranoia set in about the third block, and I was looking in all directions, storming forward but watching my peripherals to see that nobody rushed me and busted me and took my cocaine away.

I got there. Felt like I’d been walking through the desert. I walked to the very middle of the parking lot and just sat there. I could see all the streets from there, all of them except for one where 150 yards away some weeds hid the view.

There were cops walking through those weeds. I was sure of it. Cops on these streets kept passing. Every car that came by seemed like it doubled back. They were closing in.

“I know you cops are there!” I screamed. “I know you’re there. But let me tell you something. If you try to run out here and bust me, I’m gonna break the pipe and throw the coke all over the parking lot! You’ll never get me!”

I smoked until the pipe got so clogged it wouldn’t draw; I was putting rock after rock on, and the damn stuff finally just shut it down. Only then did I stand up.

“You see this?” I shouted to the phantom forces. “This is a pipe. I’m gonna break the pipe! I have no more coke!” I reared back and flung the bowl as far as I could throw it. With the lining of my coat drenched with sweat I staggered back to the Marriott.

1986: One More Hit

I got out of prison at 10 a.m. on October 15, 1986. My wife came to the prison gate and picked me up. I got in her car and did not look back. About a minute out of there I started to laugh. Not some amused chuckle, not a celebrity’s smirk or some clown’s giggle, this was loud hysterical guffaws coming up from somewhere deep in my chest. I laughed for ten minutes solid, it was that or break down completely.

There was a pizza place on the side of the road. “I want a pizza!” I shouted. There was a doughnut shop. “I want a doughnut!” There were golden arches. “I want a Big Mac! And fries!” I roared. I was like a kid on a spree, I wanted everything—and I went and got it. I was overjoyed to see my wife, to be on the outside, to be free.

Doctors tell me I am permanently disabled from having broken my neck. A doctor from the NFL told me I was a “cripple,” said I was lucky I wasn’t in a wheelchair.

I lost five or six years of my playing career, plus a whole range of post-football opportunities in the real world, due to an injury in a football uniform. I can never play football again. I’ll miss it. I loved to play, to hit, to feel that good adrenaline pumping inside me. And I loved all the things football brought me. I just wish I had been able to handle it better. Years ago I would have felt sorry for myself over a bunch of drinks or a bowl of cocaine. Not now. I have to let go of the past.

Even so, I would like to play one more game. I’d like to play middle linebacker against Tom Landry and the Dallas Cowboys in the Super Bowl. No, not the Super Bowl; I told Coach Landry that they wouldn’t go to the Super Bowl without me. Make it the NFC Championship, fourth and goal on the one-inch line, final seconds, everything hanging in the balance. If Coach Landry loses this game, he loses his job, he gets fired. They hike the ball and I come across the line, and it doesn’t matter who the running back is, I just nail him.

- More About:

- Sports

- Books

- TM Classics

- Dallas