Just after sunset on November 14, 2014, Manuel Gilbert “Gibby” Tisnado headed to his Friday night shift. He piloted his green Toyota pickup down Texas Highway 225 in the Houston suburb of La Porte, driving east through an artificial twilight of flares, beacons, and safety lights adorning the towers and tanks of the industrial plants that stretch for miles along the south banks of the Houston Ship Channel. He took the last exit, looped under the highway, and followed Strang Road until it dead-ended at the DuPont employee parking lot. It was less than two weeks before Thanksgiving. Gibby had worked so many nights, weekends, and holidays trying to meet tough production quotas that time often blurred and co-workers felt like family. And some were family: his father and two younger brothers worked at the DuPont complex too, and they exchanged embraces—abrazos—at the south gate whenever their shifts overlapped. The weather was colder than normal for Houston, with temperatures dropping into the low 30s at night. Earlier that week, Gibby had run into his father leaving the plant without a jacket, and he immediately removed his own coat and handed it over. But on this Friday evening, Gibby wore just his fireproof navy-blue coveralls. He braced himself against the cold as he passed through the gates and strode toward a squat control room near the southern edge of the six-hundred-acre compound. He knew the evening chill could bring trouble. The pesticide production unit that Gibby helped monitor—loaded with thousands of pounds of poison—had a history of malfunctioning, and whenever temperatures plunged this low, the problems grew worse.

Around six p.m., he took his place beside three other board operators on the B shift, in a semicircle of office chairs before rows of glowing security monitors and banks of multicolored warning lights and gauges. Their mission was to oversee operations inside the nearby four-story tower where DuPont manufactured Lannate, a popular pesticide used on cotton and other crops that was a major moneymaker for the company, especially abroad. The control room, built in 1969, was decidedly old-school. It looked a bit like NASA Mission Control circa the Apollo landings. None of the monitors offered views inside the Lannate tower, and the system sometimes gave cryptic warnings about equipment failures and pressure buildups during pesticide production. Operators like Gibby used radios and landlines to relay these clues to hands-on operators, wranglers who made visual inspections and, if necessary, adjustments and repairs inside the unit. His youngest brother, Robert, was working as a wrangler on the B-shift crew, patrolling the tower.

The control room assignment fit Gibby, a technology whiz who had taken apart computers for fun as a kid. He had been born in California, where he and his three younger siblings spent their first years in the beach town of Escondido. Back then, his father, Gilbert, a practicing Seventh-Day Adventist, kept everyone home to observe the Sabbath and banned TV on weekends, which forced the four kids to spend their time playing board games, stargazing, and just hanging out. When Gibby was a teen, his father moved the entire family to Texas, partly to get Gibby’s younger brothers away from the Chicano gangs in Southern California that he feared might tempt them. But their father had never worried about his eldest, a Boy Scout who always put family first. When Gibby earned his first paycheck in Texas, on a construction job, he took his siblings to a shoe store and bought them all Vans—the cool shoes they’d craved. He’d spent his life watching over others: first his siblings and later his two sons. It was his father who eventually encouraged Gibby to give up construction work for a seemingly more stable and safer career in industrial plants.

Gibby had worked at DuPont for seven years. He’d considered his assignment safe, but the job had become increasingly stressful for everyone in the division. The dimly lit Lannate tower, partially sheathed in rusting metal, resembled a small-town grain elevator. Inside was a maze of interlocking vessels, tanks, and pipes that blended chemicals to continuously produce the insecticide. The unit’s pipes often clogged, increasing pressure in the system and forcing workers to make potentially risky repairs to avoid costly production delays. To clear clogs, operators had to physically open pipes and flush out foul-smelling liquids and solids. Even this routine line-clearing could expose workers to high levels of gas. There were no external emergency stairs, and the unit’s ventilation fans on the roof weren’t functioning, increasing the risk of harmful exposure. Whenever temperatures dropped into the 30s, an ingredient used in the manufacturing process called methyl mercaptan became slushy, compounding the chronic clogs. If the situation got bad enough, if the thousands of pounds of highly toxic and flammable chemicals weren’t kept under control, the unit could unleash a major gas leak, spark a fire, or cause an explosion capable of killing dozens of workers at the plant and poisoning the air in neighborhoods that were home to thousands of people.

For more than nine hours that Friday night and Saturday morning, Gibby, his brother Robert, and their B-shift co-workers fended off such a calamity. They used heat, nitrogen, water, and their wits to clear a series of plugs that kept blocking pipes and building up pressure, which set off alarms. By three a.m., everyone was spent, and shift supervisor Wade Baker, a well-liked veteran with four decades of experience, called for a break.

Gibby stepped away from the board to phone his wife, Michelle. Gibby had been married once before; he’d become a husband and father early, quit high school, and joined the U.S. Air Force to support his family. After his first marriage ended, he’d remained a strong presence in his sons’ lives. But Michelle was the woman with whom he intended to spend the rest of his life. Things had been really bad all night, he told her, sounding subdued. They exchanged I-love-yous and then he cut the call short. He’d be home soon, he promised.

Robert made his way from the tower to the control room to rest and spend a few minutes with his brother. Gibby tended to be more serious and less outgoing than Robert, a cutup whose gregarious nature had won him many friends at the plant. Robert had just removed his heavy steel-toed boots when yet another pressure alarm sounded.

Troubleshooting that alarm fell to a rookie operator named Crystle Wise, a 53-year-old, dog-loving, Harley-Davidson-riding grandmother with electric blue eyes. By chance, Wise had chosen to take her break in a spot dubbed the “smoke shack”—between the control room and the pesticide tower. Wise, one of the latest hires in the plant’s recent wave of turnover, was still finishing her nine-month training period with DuPont. She donned her safety helmet and goggles and grabbed an oversized wrench. Then she crossed a covered passageway to the Lannate tower and opened a heavy metal door that led to a stairwell. She headed for a complex set of valves on the third floor, to clear the clog and relieve the stress on the pipes—and on the rest of the crew. What Wise didn’t know was that she was walking into a disaster.

The pesticide tower at the plant.

The repeated clogs were frustrating to workers because DuPont had completed a major renovation of the Lannate unit as recently as 2011. The company had pitched the multimillion-dollar upgrade to environmental regulators as a pollution-control measure. The plans called for all waste gases to be routed to a scrubber outside the building that company officials promised would allow them to ramp up production without increasing dangerous emissions. But the design was flawed, and gases escaped into work areas. In videos later recorded by police, the tower doesn’t appear to be particularly upgraded. The chockablock rooms on the tower’s third floor resembled the bowels of an old ship. Some tanks were labeled “out of service”; pipes containing hazardous chemicals were hand-labeled in marker. On the rooftop, neither of the unit’s massive ventilation fans were working. One was partially dismantled. According to longtime plant procedures, access to the tower was supposed to be restricted whenever those fans were out of order. But they’d been broken for months, and workers weren’t being told to take extra precautions.

In the early-morning hours of November 15, when Crystle Wise climbed the stairs of the tower to clear the latest clog, there were other, hidden dangers. Unbeknownst to Wise and the rest of the B shift, a few days earlier a delivery of chemicals had been improperly loaded into a process tank, resulting in the wrong concentration, which, combined with the unit’s chronic flaws and malfunctions, poor monitoring system, and broken ventilation system—and the wintry weather on top of that—created a potential catastrophe. A massive amount of liquefied methyl mercaptan had been building up inside pipes that snaked through the tower, undetected by Wise and everyone else.

At three-thirty a.m., Wise radioed the control room for help. She had been exposed to something and was experiencing “a reaction.” She planned to go to the fourth floor, near the top of the tower, she said. Normally unflappable, Wise sounded disoriented and frantic. Then the transmission cut off.

A stain on the floor where 23,000 pounds of methyl mercaptan leaked.

A stain on the floor where 23,000 pounds of methyl mercaptan leaked.

Robert, who had trained as a member of the plant’s emergency response team, jumped up first. He didn’t pause to replace his steel-toed boots, instead racing out in track shoes. He’d been a running back in high school, and at 39, he was eighty pounds lighter than his big brother and still very fast. He sprinted the familiar route—through a breezeway and then up several sets of metal stairs—into the tower to find Wise. She had recently come to his aid, and he was eager to return the favor. Robert was used to working through headaches and nausea, but on a shift not that long before, he’d collapsed in front of her. Though a rookie at DuPont, Wise had worked for 22 years at a tire plant in Orange, and she had dashed over to help revive him.

Another control room worker, Danny Francis, volunteered to search for Wise and followed Robert into the tower. Francis, who was 54, had known Wise since high school; both had grown up in the East Texas coastal industrial towns dubbed the “Golden Triangle.” Neither man had paused to locate respirators or oxygen tanks stored for emergencies. They didn’t know the air inside the tower was compromised. While there were alarms to alert the control room to pressure buildups in the system of pipes, critical areas of the tower lacked air monitors, which could warn workers of a gas leak.

In fact, the tower always reeked of methyl mercaptan, a gas workers called MeSH, which even in trace amounts smells like rotting onions or overripe cabbage. Over time, workers got so used to the odor that they could no longer smell it. DuPont’s standard training didn’t emphasize the danger of MeSH as much as other toxic ingredients in pesticide production. But MeSH can incapacitate people at levels of only 40 parts per million, and at 100 or 120 ppm—akin to a drop in a glass of water—it can kill. Around the time of Wise’s distress call, more than 23,000 pounds of MeSH had begun to spew into the third floor of the Lannate tower, an area with no toxic-gas detectors, as federal investigators would later find. So workers had no way to know that the air inside the tower was being displaced by poison.

Gibby watched his youngest brother disappear into the tower. Over the years, Gibby had seen Robert survive many scrapes. He had been kicked by a horse as a preschooler and hit by a car as an adult. One afternoon when they were growing up, Gibby, Robert, and their brother, sister, and cousins had all been playing army with toy guns in a field that bordered their grandmother’s house in California. They knew to be careful because the field ended in a precipice. Robert pretended to take a bullet, falling to the ground, but he began to roll and flew over the edge. Gibby ran to rescue him—only to find his brother scrambling back up with a big grin on his face. That was Bobby. He was a survivor.

A few minutes after entering the tower, Francis used an emergency phone in the fourth floor stairwell—there hadn’t been enough radios for everyone—to call the control room for help. He’d lost track of Robert and couldn’t find Wise. Another operator suggested Francis check the third floor. Francis agreed and hung up.

Soon none of the workers inside the tower were responding to radio hails. The board gauges and warning lights didn’t explain that silence, though Gibby figured there had to be a gas leak. MeSH tends to stupefy its victims before killing them through respiratory paralysis. Without any cameras inside the tower, he was operating blind. Whenever workers went down or were out of contact, one option for operators was to alert the plant’s emergency response team. DuPont had its own fire station, fire trucks, and ambulance. But Gibby knew from his own training that it could take twenty minutes to assemble a team of co-workers who’d have to be pulled from all over the complex. He knew that his brother and the others in the tower might have only minutes to live.

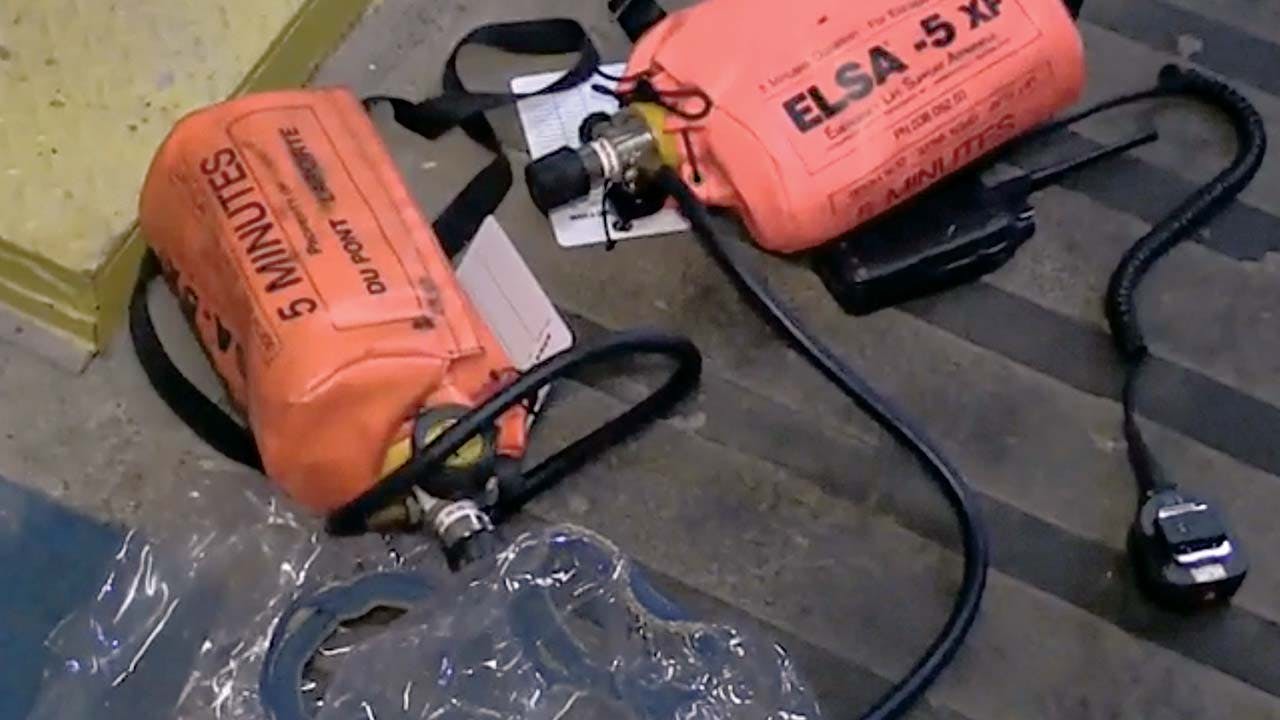

The escape packs, each affording only five minutes of air.

The escape packs, each affording only five minutes of air.

Gibby grabbed three escape air packs, small pouches with a breathing tube that would provide about five minutes of protection. With an armful of air, he ran from the control room toward the tower, moving as quickly as he could in coveralls and heavy boots. He figured a solo rescue was a long shot, but not impossible. He knew of workers who had been poisoned in the unit, been revived, and suffered little or no permanent damage. He had to try.

E. I. du Pont broke ground on his first mill in 1802 along the banks of the Brandywine River, in Delaware, to supply early America with gunpowder. Later the du Ponts also manufactured dynamite. But over the centuries, the corporation became world-renowned for its innovations, inventing everything from Teflon to nylon. In the aftermath of World War II, the growing company bought waterfront property outside Houston and erected processing units along the Upper San Jacinto Bay.

The site attracted the DuPont company for the same reasons that led so many other chemical manufacturers and refiners to colonize Houston’s outskirts, creating one of the world’s largest petrochemical complexes. The plethora of plants, the Port of Houston, and the far-reaching rail and road networks of the “Petro Metro” made it easy to obtain raw ingredients and to export products worldwide. Over six decades, DuPont developed diverse manufacturing units at La Porte, including polyvinyls, textiles, sulfuric and hydrofluoric acid, and “crops,” the corporate euphemism for pesticides and herbicides. The property has its own deepwater dock and is crisscrossed by rail tracks and pipe racks.

From its roots in gunpowder and dynamite, DuPont had by the seventies and eighties become known for its stellar safety record. The corporation is credited with pioneering protocols for handling highly hazardous chemicals years before the federal government strengthened its own standards, in 1990. DuPont’s engineers even won an international safety award for the Lannate unit, through a design that allowed the company to radically reduce shipments of a notoriously toxic ingredient called methyl isoncyonate, or MIC. It was MIC that escaped from the Bhopal pesticide plant in India in 1984 and formed a toxic cloud that killed more than 2,200 people, still the world’s worst industrial disaster. With the redesign, DuPont could make MIC on-site in small batches, storing only what was needed, instead of receiving large, volatile shipments. The Delaware-based corporation often claimed that its plants had been entirely accident-free for decades.

Wade Baker, the oldest son of a Houston homicide detective, grew up near the La Porte plant, and even as a teen, he considered the operation to be the best and safest around. After high school, Baker began to visit DuPont every week until he finally got hired, in 1974, a year after he married his high school sweetheart, Debbie. Then he helped his two brothers land jobs there too.

The sign welcoming visitors to the complex on Strang Road.

The sign welcoming visitors to the complex on Strang Road.

Baker started in the plant’s polyvinyls unit, which makes, among other products, safety glass for car windshields. A promotion later made him shift supervisor over the pesticide unit. In the decades before the attacks of September 11, 2001—after which plant security was tightened—Debbie and their two children had often visited the grounds for family cookouts, barbecues, and concerts. But by the time Baker’s son graduated from high school and sought a job at the plant, things had changed. Baker told him to apply elsewhere. DuPont no longer felt like a good place for family.

The cultural changes came as DuPont executives faced pressure in the aughts to increase profits for shareholders and to sell off less-lucrative product lines. In 2003 DuPont spun off its textile division into a subsidiary called Invista, initially promising La Porte employees, most of whom belonged to the International Chemical Workers Union, that they’d remain part of the DuPont family. Then Koch Industries acquired Invista. One of Baker’s brothers found himself working for Koch that way. The Invista transaction turned contentious when Koch sued DuPont in a Manhattan federal court, accusing the company of artificially inflating textile profits by deferring maintenance and covering up pollution problems, including a major benzene release in East Texas. The alleged problems in the former DuPont division were such that Koch, whose owners are known as crusaders against government regulation, provided proof of DuPont’s past violations to the EPA and paid a huge voluntary penalty. The court fight with DuPont was settled in 2012.

DuPont experts continue to deliver lectures at global safety conferences and make millions peddling their safety programs to other companies, with results that they say have been proved. But the corporation’s pristine safety reputation suffered after toxic releases killed two workers at chemical complexes in New York and West Virginia. One longtime DuPont employee was fatally poisoned in 2010 after cheap plastic tubing burst inside a shed at DuPont’s plant in Belle, West Virginia, dousing him with phosgene, a gas that had been used as a chemical weapon in World War I. That same year, an explosion killed a contract welder and injured his co-worker in Buffalo, New York. They hadn’t been warned of a possible gas buildup inside the tank they were repairing. The U.S. Chemical Safety Board, a small federal agency that investigates the nation’s worst industrial chemical accidents, reviewed both cases and criticized DuPont. Company officials had failed to follow their own maintenance and safety rules, the board said. “In light of this, I would hope that DuPont officials are examining the safety culture company-wide,” the board’s former chairman John Bresland announced in July 2011.

DuPont’s CEO, Ellen Kullman, has faced continued pressure to restructure the chemical empire and boost its bottom line from Nelson Peltz, a billionaire hedge-fund investor whose firm is one of DuPont’s largest shareholders. In 2014 company officials cut new deals. In June its Japan-based competitor Kuraray acquired the polyvinyls units. Then DuPont announced plans to spin off its acid manufacturing plants into yet another separate subsidiary called Chemours. The dizzying series of shake-ups affected two of the La Porte plant’s largest divisions. But the pesticide unit remained, generating what workers estimated were about $250,000 a day in profits.

While the Lannate unit was profitable, it saw its share of turnover. Production details were top secret—and so complex they took about five years of hands-on experience to truly master, according to Gregg Hill, a former DuPont operator who spent seventeen years in the unit before retiring, in 2007. Most Lannate workers didn’t stick around that long: some suffered headaches; others hated how the fumes tended to linger on their clothes and in their mouths after shifts ended. In fact, the chemicals involved in the process, like MeSH and chlorine, are branded highly hazardous toxic chemicals by the EPA. And, as the unit’s training videos emphasized, the final product, methomyl, is a compound so toxic that a quarter of a teaspoon can kill.

The company shake-ups left Baker saddled with training a number of rookies after experienced hands retired or transferred out. At home, he downplayed the hazards. He didn’t want his wife to worry. But she and their children knew that he’d been poisoned twice inside the unit. The first time was years ago, when his daughter, Laura, and son, Brent, now in their thirties, were still small.

Baker got exposed again in 2012, when he was near pesticide that leaked into a drain. Plant personnel transported him to a hospital, where he was treated with atropine—administered as an antidote for methomyl poisonings—after an elevated level of the poison was detected in his blood, his son and daughter recall. When Baker returned home, his skin was “lime green,” his wife says. Baker told her, “Now I know what a roach feels like when you spray it. You twitch, you convulse, and you vomit. I hope I never get into that stuff again.”

In October 2014 Randy Clements, Baker’s boss and the longtime pesticide unit supervisor, became La Porte’s plant manager, the fourth change in the top job in only five years. Clements took over at the same time that some workers were worrying about job security and others chose to retire. All that turnover increased pressure on Baker, who fielded constant questions via cellphone on duty and off. Baker, too, wanted out. He’d turned sixty and had bought a brand-new RV. He and his wife had already taken the first of what they expected would be many trips: a long loop through the Hill Country. Even while they were gone, Baker’s phone rang constantly with calls from the plant.

On the night shift that began on November 14, Baker brought a battered plastic lunch box that was covered with plant safety stickers. Inside was a bowl of chili that his teenage grandson had fixed for his dinner break and a copy of his résumé. Baker had recently submitted an application to retire from DuPont and transfer to work temporarily for the newly formed Chemours, to take advantage of incentives DuPont was offering as it formed that spin-off company. He figured it would be a short-term job while he and his wife made arrangements for their future.

The Tisnado siblings, Michael, Gibby, Lanette (Soto), and Robert.

At 48, Gibby was no longer a nimble high school soccer player. He weighed 230 pounds, though he remained strong and physically fit. With the air masks in hand, he retraced his brother’s path, covering the fifty yards that separated the control room from the door of the Lannate tower. Gibby clambered up two flights of stairs and ran into someone he hadn’t expected to find, another co-worker, who had separately entered the building in response to Wise’s distress call. The man had searched the second floor but had become disoriented after being exposed to leaking gas. He was nearly incoherent as Gibby handed over one of the three escape air packs, pausing to fit the breathing bag over the other man’s face.

Gibby then placed a second escape air pack over his own head, leaving only one unused. He handed the man his prized Houston Dynamo soccer cap—Gibby was a season ticket holder—and directed him toward the exit. The air packs bought Gibby at most ten minutes to search, probably less given the stairs he’d be climbing. So Gibby paused at a second-floor storage area to retrieve a heavier thirty-minute air tank and a more elaborate mask. Then he pulled a hand-activated alarm located in the stairwell. It sounded faint amid the cacophony of heavy machinery.

At least Gibby now had a better idea where to look for his brother. He knew that both the second and the fourth floors had been searched, so he headed for the third floor. Inside one of two cavernous rooms, Gibby found Robert sprawled on the concrete. He knelt down to place an air mask—the last escape pack—over his brother’s face. He carried Robert away from a dark pool of chemicals on the floor and into a smaller room protected from the spill area by a red fire door. Then Gibby collapsed. They were only ten feet from a short flight of stairs that led out to a parapet in the open air. The sign on that door read “No Exit.”

As the brothers’ air was running out, help was on its way—but slowly. Between three-thirty and four a.m., emergency response team members from across the complex began to assemble. Radios and yellow emergency phones came alive with chatter. Everyone was looking for Baker so he could take charge of the team. They expected him to be prepping for the dawn shift change inside his office, located in a building between the control room and the tower. But Baker wasn’t responding either. Soon it became clear that he too had gone into the tower. Perhaps, as co-workers would later speculate, he was responding to the pressure alarm or to Wise’s distress call, or maybe he went in because he realized a catastrophic leak was occurring and risked his life to stop it. Without Baker, the rescue effort was further delayed.

A few responders ran to the DuPont fire station to retrieve equipment. None of the company’s three trucks ever reached the tower, according to several witnesses present that morning. One had a dead battery. (Industrial firefighting facilities in Texas are exempt from fire marshal inspections. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has jurisdiction, but it had not inspected the DuPont plant since 2007.)

No one had a diagram of the Lannate tower. So the team waited as a worker drew one from memory. And no one knew just which chemical had poisoned the air or whether company firefighting equipment would protect them. Despite their uncertainty, small groups of would-be rescuers began to enter the tower. The searchers took several forays into the unit, since climbing the stairs and searching unfamiliar rooms took a lot of time and air. None of the rescue team members had formal medical training, DuPont would later disclose.

About thirty minutes after Wise’s distress call, a DuPont emergency response team member called 911. “We have a possible casualty, five [workers], my medics are telling me,” he told a dispatcher who worked for the City of La Porte. She immediately asked, “Can you tell me, is this any risk to the public?” “No ma’am, it is not,” he assured her.

La Porte, a city of 35,000, bears primary emergency response duties for a massive industrial zone that houses four dozen plants, including the entire DuPont complex. City officials issued an alert via Facebook and robocalled residents, most of whom were still asleep. Later it became clear that despite its assurances, DuPont had no fence-line air-quality monitors in place to determine whether dangerous levels of toxic gases had reached nearby neighborhoods. The truth was that no one knew early Saturday whether the air around the plant was safe.

As dawn broke on a cloudy, cold morning, dozens of day-shift workers arrived at the plant gates to the sound of sirens wailing the signal to “shelter in place.” Those sirens sounded three times. For hours, some night crew workers remained crammed into guard shacks, administrative buildings, control rooms, and other spots.

Harris County sheriff’s deputies arrived to find chaos at the plant. One deputy scanned the skies for a poisonous cloud as he maneuvered his cruiser down Strang Road. About half of the B-shift crew was missing, and DuPont workers had taken longer than usual to set up a command post or contact Channel Industries Mutual Aide, a cooperative service of Houston plants that offers help during accidents. Deputies kept asking which employees were dead, who was missing, and who’d been transported to the hospital. No one seemed to know. One deputy was dispatched to Bayshore Medical Center to locate witnesses and survivors. Some believed Crystle Wise, the first to call for help, had gotten out and simply gone home.

Contract security guards were assigned to keep everyone away from the pesticide tower and escort emergency responders. A few security guards who patrolled the area without gas masks or air tanks later coughed so long and so hard that they spit up blood. Others developed infections and skin irritations. One ended up in the hospital overnight and received a blood transfusion.

When Barbara Acker, a former DuPont laboratory technician, heard about the accident, she felt a shiver of déjà vu. Seven months earlier, in April 2014, Acker had been asked to serve as an observer in an emergency response drill. That scenario involved a worker “down” during a gas leak at the pesticide plant. Then it called for another worker to respond without a respirator and get poisoned too. With two down, they’d see how fast emergency crews responded. Acker remembers how plant radios cut in and out as responders attempted to coordinate their actions. “We just sat in the ambulance for what I thought was forever,” she recalled. “It just seemed like a comedy of errors to me. The guys were in their fire gear and they were kind of standing around.” DuPont’s response to the real emergency seemed just as flawed, she thought. Why hadn’t DuPont learned from that drill?

Acker had been an outspoken safety advocate at DuPont. Over the years, she’d made a series of written and verbal complaints and documented what she considered improper storage of dangerous chemicals in a process lab. She’d photographed leaking bottles of acid, jumbled-up equipment, and outdated and unlabeled samples of poisonous and volatile chemicals. Her supervisors didn’t seem interested. Then, in September, two months before the accident, her job was eliminated as part of company downsizing.

Gibby’s oldest son, Chris, worked an overnight shift on November 14 at a nearby refinery. On his drive home before dawn, he smelled a “horrible skunk-like odor” along Interstate 45. At first he figured he’d spilled something foul on his uniform. So he opened the windows of his red Dodge Ram pickup, but the stench got worse. Then he forgot about it as he pulled into his driveway in a Houston subdivision. He undressed and rolled into bed next to his sleeping wife.

He remembered that stench a few hours later when the cellphone on his bedside table buzzed with an incoming call. It was his uncle Michael, who also worked at the DuPont plant. “Something may have happened. I think your dad’s missing.” Michael was off duty but had been woken early by panicked co-workers calling about a gas leak at DuPont.

Chris jumped out of bed. His wife was awake, tending to their small children, and had already seen vague reports about DuPont on television and Facebook. Toxic releases happen too often to make the news in Houston. But this time, it appeared that workers were missing, maybe three or four. Still, Chris did not worry. He kept thinking his father would simply hole up somewhere until the situation was under control.

Chris dressed and drove to his grandparents’ house in the neighboring city of Pasadena. Their brick house, sheltered by a huge tree, is a natural gathering place for the Tisnado clan. The sign on the front door reads “Mi Casa Es Su Casa.” The backyard brims with carefully tended flower beds, and the pergola over the patio is bedecked with jasmine vines. Children and grandchildren carry their own keys and come and go as they please. As that long morning passed, family and friends kept arriving, filling the house and spilling into the yard.

The other families had hunkered down too, waiting for news. Everyone had received the same generic early-morning message from plant officials: there was an emergency, workers were missing. Baker’s son drove to the plant gates. Everyone made calls. They all heard different stories from plant employees, but no one had any answers.

A rumor the Tisnados heard that morning gave them hope: Gibby had managed to save Robert, and he’d been transported to Bayshore Medical Center. Gilbert, the patriarch, reminded everyone that Robert had survived a lot of near-death experiences and had always been lucky. Almost everyone remembered the story of how Robert had fallen off that cliff—and then crawled back up smiling. “He’ll be fine,” Gilbert predicted. They called hospitals, hoping to find a Tisnado in a room somewhere, but no one had been admitted under that name.

Eventually they learned that Danny Francis, the control room operator who’d gone with Robert to try to rescue Wise, had been taken to Bayshore. Francis had blacked out, fallen down a stairwell, and landed in a pocket of clean air. Somehow, he’d woken up and managed to crawl out. Someone later found him lying on the ground outside and called an ambulance. Surely others had survived too. But two, three, then four hours passed without updates.

Around two in the afternoon, DuPont plant manager Randy Clements, a confident man with an out-of-season tan and a shock of white hair, pulled up at the Tisnados’ house with an entourage of executives in business suits. He knew all three Tisnado brothers and had sometimes taken pesticide crews out for steak dinners when they met production quotas. Yet Clements kept mixing up the brothers’ names as he spoke to the family. He assured them that DuPont would cooperate with all state, local, and federal investigations and would get to the bottom of what had gone wrong. And he delivered the bad news: Gibby and Robert had died in the accident.

Clements offered few details, though, and it would take a long time before family members could piece together what had really happened to the brothers. As the family would eventually learn, members of the plant emergency team had found both men early that morning on the third floor. Robert was lighter and fitter than his brother, and his co-workers hoped he might still be alive. They hauled him down all those stairs and into the plant locker room next door, where they made attempts to revive him. But he was declared dead when trained medics arrived.

It wasn’t until five o’clock that afternoon that the unit was deemed safe enough to recover bodies. Wade Baker had perished near a set of valves on the third floor that he or Wise may have opened to relieve pressure in the system, though it remains unclear precisely what actions Baker and Wise took. Baker collapsed near a pool of foul-smelling liquid with a bluish tinge.

Wise had managed to escape that room, then collapsed in a back stairwell between the third and fourth floors. None of her would-be rescuers had found her because they’d all entered another stairwell, on the opposite side of the building. She had fallen beside her radio and her wrench.

The Tisnado brothers died together, though by the end of that day, only Gibby’s body remained on the third floor. Beside him, two 5-minute escape packs were empty, but the spare 30-minute tank still registered full. He died trying to connect that air tank to his brother’s mask.

All four employees’ uniforms were so contaminated that DuPont officials removed and disposed of them as toxic waste. Each of their fireproof coveralls had been personalized: Crystle. Wade. Robert. Manuel. “There are no words to fully express the loss we feel or the concern and sympathy we extend to the families of the four employees who died,” the company said in a statement two days after the accident. DuPont officials halted Lannate production and launched an internal investigation into the accident, promising to correct any problems before restarting the unit. Investigators haven’t yet identified the exact sequence of events that caused the unprecedented release of twelve tons of MeSH.

At first, Gilbert Tisnado had faith in the company. For a few weeks after the double funeral, he went back to work at the La Porte complex for KBR, a maintenance and construction contractor for DuPont. He’d worked at chemical plants for decades and wanted to believe in DuPont’s safety reputation. He knew accidents happened, and he wanted to think the leak had resulted from a freak accident. His surviving middle son, Michael, still works at the plant. But Gilbert soon found he couldn’t continue to work there, after what he learned in preliminary briefings provided to the families by the Chemical Safety Board and from investigative reports published by the Houston Chronicle. He quit KBR and has joined his sons’ widows and the other families in suing DuPont for negligence in state court.

Certain facts particularly outrage Gilbert: Access to the unit should have been restricted because of its broken ventilation fans, yet workers were repeatedly sent inside without additional protections well before the disaster. Relatively inexpensive equipment—automated alarms, portable or stationary air-quality monitors, and better radios—could have spared his sons’ lives by alerting them to the dangers that lurked in the tower that night.

The federal government has taken belated action. In May OSHA proposed fining DuPont $99,000 for violations related to all four deaths. Then in July OSHA added another $273,000 in proposed penalties for problems uncovered elsewhere in the plant. A top official announced that DuPont would be added to the agency’s list of the nation’s most dangerous employers and targeted for additional corrective action through the Severe Violator Enforcement Program. In response to multiple government investigations, DuPont named a new plant manager in June. The company didn’t respond to specific questions for this story but, in a statement, promised to revamp equipment and procedures before restarting the unit.

The penalties and company assurances seem small to Gilbert and his family. He and his wife canceled the big fiftieth-wedding-anniversary party they’d planned with all four of their children. Their sons’ smiling faces appear in the family portraits that line their shelves and walls, but family gatherings are more somber now. Gibby’s widow comes alone; Robert’s wife is raising their young children without him. Gilbert has accepted that Robert died trying to rescue his co-worker. He takes some comfort knowing that Gibby helped save another man’s life and perished trying to save his brother. His sons died heroically, but, he says, their deaths could have been easily prevented if their employer, a multibillion-dollar corporation, had invested in upgrades and followed its own rules. “It wasn’t necessary for them to die.”