For years I tried to keep my body in shape with intermittent spurts of swimming a mile a day or with morning runs around a nearby junior high school track. My efforts at health consisted of crash diets and haphazard but short-lived efforts to cut all sugar, salt, coffee, and alcohol. After my daughter’s wedding, fatigued and fattened, I thought it would be wonderful, for a change, to do in an efficient way what usually took me a season’s struggle. Just once I longed to put my body into someone else’s willing hands.

The most willing and most expensive hands I could find wore at Texas’ famous health spa, The Greenhouse. Located halfway between Dallas and Fort Worth, at the back door of the Inn of Six Flags, The Greenhouse has the reputation of being a high-class fat farm where such notables as lady Bird Johnson, Princess Grace, and Sissy Farenthold as well as countless jet-setters, go to erase exhaustion and firm flesh at the steep tab of $1380 per week As Stanley Marcus explained in Minding the Store: “Our interest was in the operation of a facility so superior in luxury and results that thirty-five socialites from all over the nation would come to Dallas every week of the year and eventually become regular Neiman-Marcus customers.” To ensure such results, owner Great Southwest Corporation, in conjunction with cofounders Neiman’s and Charles of the Ritz, employs a staff of 108 to serve each week’s class of 35 guests.

This ratio of six hands to one body was what I was looking for as, besides losing pounds and inches, I hoped to lose the signs of middle-class, middle-age depreciation as well: I expected at last to get rid of fat ankles, puffy eyes, hangnails, split ends, callused joints, splotched skin, bumpy bottom, and sagging belly.

To this end on a summer Sunday afternoon I walked up the boxwood-bordered blue pavement through the trellised doorway of the luxurious pavilion. Entering the hermetically sealed coolness of its muted yellow, pink, and green interior, I was ready to be taken in hand.

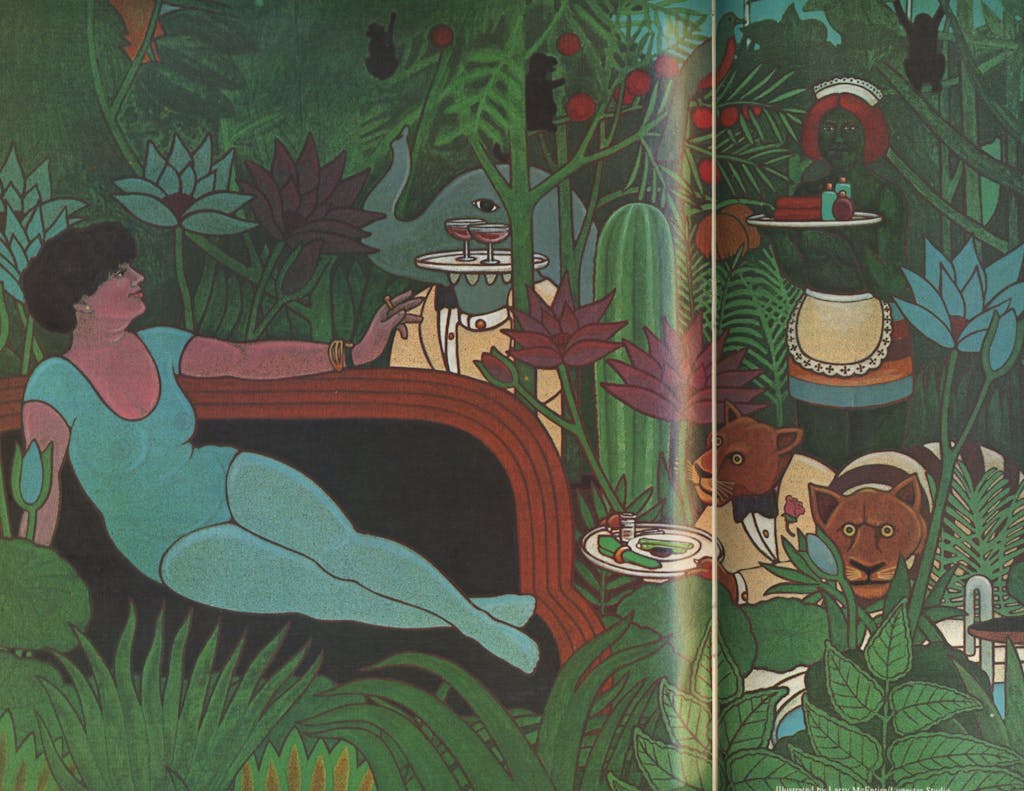

Which I was. While one young man in dark suit embellished with a pink rosebud whisked away my car keys, another—identically dressed—took my bags. These boys, and two housemaids in eyelet aprons and starched caps who hurried by on their way to turn back coverlets and lay out towels, provided my first glimpse of the staff. My bag carrier led us through a vaulted, glass-domed garden (hence, The Greenhouse). Around its heated pool a hundred pots of yellow mums nestled in beds of schefflera and trailing ivy; above it, sunlight filtered through the lush greenery of three dozen hanging baskets. My room was on the first floor, right off this atrium. Large and private, tinted in palest celery and lemon, my elegant quarters offered, for my leisure, a color TV set, a mammoth dressing area with star’s makeup mirror, a sunken marble bathtub, and, everywhere, pots of fresh green plants. On an antique writing table waited a welcoming letter from Neiman-Marcus: “To make your stay as effortless as possible and in the event you forgot to pack your charge plate, an extra plate is enclosed for you.” On the marble counter lay Charles of the Ritz’ pink-bowed favors: scented body lotion and talcum powder.

My white-capped downstairs maid arrived to plump the six assorted ruffled pillows on my canopied bed and to explain what was forthcoming. Breakfast would be served to me in bed at seven. My schedule for each day would be on my breakfast tray, along with a fresh rosebud. My room key was to be left in the door, for my convenience and hers. My things would be safe, but, if I liked, my good jewels could be placed in a lockbox in the office. The doctor would be by before supper to work out my diet program. I was to join the others in the parlor at six.

When she left, my first thought was to nap beneath the eyelet counterpane. It seemed in keeping with the atmosphere of this place where all my needs were being looked after. Somewhat anxious about my first plunge into The Greenhouse group, however, I did what I surmised the typical woman was doing upon her arrival: I hung up my clothes in a corner of the vast double closet. The sight of my selection of four pairs of cotton pants and six shirts made me uneasy. Our advance letter (on pale green paper embossed with the pink rose) had assured me that “dress for dinner and evening entertainment at The Greenhouse is informal, with the hostess gown being the most popular.” A phone call to the Aunt Doris of a friend of mine, a Greenhouse regular of many seasons, had confirmed what I suspected: that their view of what was informal was vastly different from mine.

Entering the parlor on the stroke of six—dressed in my best mauve cotton pants with matching embroidered top—I could see—confirming my suspicions—that everyone assembled wore a rich and rustling caftan, an exquisite import from Morocco, France, or Italy. If their best jewels had been locked away, their second-best adorned every throat and ear. A pigeon’s egg of jade or malachites in a rare setting matched the green of a sleeve or the border of a hem.

Our formidable red-haired director, Myriam Wood, guided us through the introductions. Formerly of Brazil and Bermuda, recently hired Wood had gone from a size 14 to a size 10 since taking the job, so could present herself as a living example of what The Greenhouse could do. Only eight of us were from Texas, the rest from sixteen states and both coasts. About half were newcomers and the other half old faithfuls, some of whom had come twice a year since the spa opened in 1965. We did not come in middle sizes, being either size 8 or size 16. We did come mostly in middle age—although the age ranged from as young as eighteen to nearly eighty.

Our group had six mother-daughter teams, as well as a trio of stunning Russian sisters. (For such groups The Greenhouse provided two-bedroom suites with adjoining living rooms.) I visited with a lovely Sophie Newcomb student named Mary Evelyn, who was unhappy that she had just cut her long, thick hair into a blow-dry wedge. She and her mother were part of the Florida Five who had decided, as a lark, that it would be fun to come together.

Even those without kin gathered together with old friends who migrated to the spa at the same time each year. Aunt Doris had said that these reunions were one of the best parts of her visits. A few—one such was a strikingly handsome, imperious Chinese woman, a former New Orleans restaurateur—used The Greenhouse as a base of operations to keep in touch with business acquaintances in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. It was no wonder that the pale green, rose-imprinted note had welcomed me to “our Greenhouse family.”

As we got acquainted, a young man in dinner jacket passed among us with champagne glasses of chilled, sweetened, watery fruit frappe. This was our evening “cocktail.” As the advance letter had made clear, “In keeping with the high ideals and standards of good health that we endeavor to maintain, alcoholic beverages are prohibited at The Greenhouse.” And that ban helps make it one of the most elegant drying-out places in the world.

After our allotted 25 calories and 30 minutes of socializing, Wood led us into the cozy dining room where—before a cluster of small round tables with fresh flowers—a buffet supper awaited us. Artfully arranged, the scant food was a feast to the eye, if not for the stomach. “You may have two of these,” the young man in dinner jacket murmured to each guest as she reached for the cauliflower florets. “You get one of these.” He indicated a cube of beef on an artichoke bottom. It was clear that, even at the table, our decisions would be made for us.

Monday morning we all suited out in the regulation blue leotards, blue tights, and yellow terry robes supplied fresh daily in our individual sizes. Pinned to our robes were our green-tinted, rose-adorned schedules. With our hair pulled up with ribbons or tied back with scarves, and our faces scrubbed clean of makeup, we looked quite different from the night before. I felt more at home; stripped of jewelry and cosmetics, the group was indistinguishable from the Trim & Swim whirlpool set at home.

A bedside brochure had spelled out what was in store for us: a half-hour Wake-up session, 40 minutes of Swing and Sway the Greenhouse Way, one 45-minute Water Class, and one Spot Reducing Class. In addition, we could opt for a 15-minute morning walk and a 30-minute Posture/Relaxation Class or a Dance Class in the late afternoon. We were asked to wear our tights to keep our leg muscles warm and to wear a bra except during Water Class.

Over my breakfast tray I had quickly calculated that they were talking about three hours and ten minutes of perpetual motion. It began to dawn on me that the key to The Greenhouse was no more and no less than any program which called for three solid hours of exercise. I wondered just how many women actually got down to this hard core of effort hidden beneath the candy coating of The Greenhouse’s loving care. Most of us started out the day with good intentions; all were present for Wake-up. Not many, however, joined those of us who signed up for the after-breakfast walk. A young instructor led us at a fast clip past a golf course, over a rustic bridge, to a bubbling stream complete with a bevy of gliding swans.

If the women from the night before had seemed to be what I expected, on the morning walk I found them ready to make friends with me. Striding along beside me on the way to the pond was the advertising manager of a Tandy Corporation spin-off. “What do you do?” she asked, moving quickly over my admission that I write to tell me that she had come to The Greenhouse to quit smoking. Walking beside me on the way back was an island-tanned Eastern socialite who had brought along special jogging clothes for this early-morning walk. She came each year for two weeks to work off the pounds she put on each winter during eight weeks in the Caribbean. Finding that I was recently the mother-of-the-bride, she readily assumed that my “small family wedding” had been just like her daughter’s, and talked throughout our walk of her caterers and flown-in flowers.

Wake-up, the first regular class of the day, had even the fattest, most lethargic guest out by the pool at 8:15. For this class and the next we worked out on cotton mats placed in a circle around the water, with the instructor at the end by the record player. The inspiration for the full attendance at Wake-up as well as a certain jockeying for ringside spots was its leader, Toni Beck.

Beck, now 51 and a former New York dancer, heads choreography at Southern Methodist University. She had designed the exercise programs for The Greenhouse and had supervised and trained its other instructors since its start.

In dark brown leotards and no tights, with loose dark brown hair, she was as trim and limber as a ten-year-old swinging from a tree. Using a combination of yoga breathing, isometrics, aerobics, and flow—the theory that your motion should require all your attention, leaving you neither bored by being too easy nor discouraged by being too hard—she urged us to imitate the ease of her body for the improvement of ours. “OK, people, right leg up flex foot breath out leg down point toe now again breathe in left leg up flex foot breath out leg down point toe and again right leg up . . .”

“That’s good, people,” she would encourage us as we strived to firm our legs, tighten our stomachs, reduce our hips and thighs, loosen our shoulders, and extend our backs. “That’s good, there,” she would say approvingly to one of us who strained especially hard. Not having come with either kin or friend, I worked out between two other newcomers. One, a gum-chewing lawyer from Tennessee, had come to recover from foot surgery; the other, an art dealer from New York with Sassoon-cut hair, was eager to work off a wine belly pleasantly acquired in the south of France. Both, like me, meant to leave no leg unlifted to do it right.

“You, there,” Beck gestured to me between a breathe in and a breath out. “See me after class.” Afterwards she gave quick remedial help. “You are using your back instead of your stomach on the standing and bending exercises.” She took my middle and shifted its weight to demonstrate. “You may feel at first you are bending forward. Feel it here?” I did, and, at her instruction, let my stomach slide somewhere out of sight above the pelvic bone.

Disciples of Beck—half her age—instructed our other classes. The attitude of many of these bouncy, shapely women was vastly different. Their condescending air and sing-song recital of exercise instructions had a soft edge of contempt, as if they assumed all of us were pudgy bonbon-eating members of the idle rich.

We conjectured that as a girl in Alabama she must have had a stag line a mile long. With a toss of her head, she let us know she still did.

We moved through almost an hour of drills set to music, using aluminum poles to pull our legs close to our chests for back rolls, or to sway our torsos for waist tugs. In time our bodies anticipated the motions of each coyly named exercise as its familiar part of the song came along. This repetition allowed us to perform routines as our minds wandered—a definite loss as far as I was concerned. The essence of flow and yoga that Beck had supplied had been replaced by the fatigue which accompanies rote drill.

My next exercise class, after a late lunch, was 45 minutes of rolling, shoving, and clutching hard-rubber yellow balls around the pool. This is called Water Class. The 50-meter pool had a low tile ledge along one length and a waist-high bar along the other. Our energetic pony-tailed instructor drove us cheerfully through our paces as we tucked the balls under our knees and paddled around the pool; sat on the ledge with a ball between our knees and raised and lowered our thighs; held onto the metal bar with our hands and lifted the ball between our feet; or, with our feet hooked on the bar, pushed the balls up and down with our hands. We gyrated over and over with a yellow ball under each arm in a dandy rotation called the log roll. “Come on, ladies, let’s all line up with our feet apart and the balls in our hands,” she cajoled us. “You can practice these same routines at home in your own pools, ladies.”

The smaller, individual exercise classes, called Spot Reducing, were held in ground-floor studios (“everything from the neck down, on the first floor”) similar to ballet classrooms, with one wall of mirrors, two of barres. For these 30-minute sessions we were divided by size and shape for zooming in on special problems. In my class I had Mary Evelyn, her mother, and two other members of the Florida Five. We exerted peer pressure on each other to attend, as these were the classes most likely to be defaulted—they were so small that every eye was on you, and, worse, they were held late in the afternoon.

The last exercise class of the day was Dance. Every day I went in at 4:30 exhausted and came out at 5:00 energized. This instructor was a dance student of Beck, and, although younger and less experienced, moved with much the same looseness and joy. She thought we were there because we wanted to be, and her attitude made it true. Betty, a plump regular from Alabama, was the star. In the mirror we watched first the instructor, to get the steps to the hustle, and then watched Betty, to see how someone with natural rhythm did it. “Where did you learn to dance like that?” I asked her in envy. “Honey, in Mobile when I was growing up every girl learned to dance and paint china.” We conjectured that as a girl in Alabama she must have had a stag line a mile long. With a toss of her head, she let us know she still did.

For the finale, our leader folded down a wood floor, and we put on our shoes and followed her in a little shuffle-ball-change like real tap dancers. It was a marvelous ending note to move our bodies simply for the pleasure of moving them, a fine echo of Beck’s beginning.

Needless to say, not everyone followed the whole day’s strenuous exercise program. A few of the regulars who had appeared for Wake-up did not do much else but sunbathe by the small outside pool or catch up on their letter writing until suppertime. As Aunt Doris had said on the phone, intending to reassure me that it didn’t all have to be as much work as it sounded like: “They try to get you to do everything, but you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to. You can read in your room or take a nap if you’d rather.”

No one, however, missed the one real chance we had to put our bodies into someone else’s strong hands: the daily one-hour massage. My masseuse, Edith, a German physical therapist from Hamburg, had been hired by Mrs. Stanley Marcus when The Greenhouse opened. She found it a much more cheerful place to work than the hospitals she was used to; she was fond of “her” women, most of whom asked for her year after year.

After showering and warming my muscles in the sauna and whirlpool, I disrobed in a white antiseptic cubicle which had the air of a doctor’s examining room. As Edith covered me with warmed unscented Nivea oil, she worked each muscle through its knots, spasms, or cramps until I became as relaxed as a sleeping cat. Her hands toned my nerves, recirculated my blood, erased lines and tensions. She worked lumps from my neck and feet that had been there always. This was what I had paid my money for; I was not disappointed. Each day I left her room an anonymous contented mass.

After the refreshing equality of the exercise classes, where in our terry cloth robes we seemed beyond the usual female competition, they painted our faces back on for us. I entered the giant pink and green floral-papered Charles of the Ritz Salon (“everything above the neck is on the second floor”) with the highest hopes. Here I expected the greatest transformation for the least effort. Here, certainly, I would be the passive receiver of the artist’s skills. An acquaintance of mine in Austin had promised that this was the high point of The Greenhouse. “I love the makeup class best of all . . . I look forward to it all day long. Every time they try a new eye shadow or a new foundation I think I’m starting over. I’ve been to Elizabeth Arden; I’ve been to all of them. And I always think that this time they’ll turn me into a 110-pound beauty.”

The six of us in our before-lunch class—Mary Evelyn, her attractive olive-skinned mother, two old regulars, me, and an anxious woman who wore sunglasses throughout the session—were seated in a brightly lit classroom at individual vanities. Assorted blushers, eyeliners, brushes, foundations, cleansers, creams, and cover-ups had been selected and set before us. In the magnifying mirror before me I had no trouble identifying what needed correcting on my particular face: brown splotches from backpacking in the sun, dry skin, tired, turned-down eyes, permanent laugh and scowl lines, other crow’s-feet of aging. I expected a Glamour magazine make over where ordinary people were turned into cover girls by the re-arching of a brow, the relining of a lip, the hollowing of a cheek, or foreshortening of a nose.

Instead, we got almost a parody of a beauty school. The two glossy Chasritz girls set out to “paint us beautiful.” “Charles of the Ritz,” explained one, “knows that all women have pink undertones to their skins. He makes all his makeup just for you.” Mary Evelyn’s mother and I, with blue and yellow casts to ours, were in hard luck.

We were all instructed in the current facial fashion. Laboriously we copied from the blackboard onto our green-tinted makeup analysis charts the same seven steps for creating our eyes, the six steps to making up our face, the five steps to applying lip color.

All our faces, fat or thin, young or old, puffy or sagging, emerged identically drawn and colored. We each marked off an angle between mouth and eye for a diagonal streak of blusher. We each drew our brows to a specific point on a line extended from nostril and eye. A whitish cream concealer was applied under the eyes, so those women who started out with dark bulging bags ended up with white bulging bags even more visible than before.

In addition to this standardized approach, we were subjected to continual hard sell. I got by with a lipstick called Bronze, a lipbrush, a cocoa-colored fast-setting eye gel called Wood Sage, and an eye brush (total, $13.65), these being the least pink products I could find. Mary Evelyn’s mother bought about half. The hesitant woman in perpetual sunglasses got the whole works.

My dislikes and failures in other beauty areas were more my fault than the Salon’s. I disliked the hourly daily facial as much as I loved the massage. Most old regulars liked it better: it required less effort and you could keep your clothes on. When the Chasritz girl had cleansed and packed my face and left me on my back to “set,” I felt I was strapped in a dentist’s chair. Most of all I could not bear the cloying Chasritz perfumes. In the makeup class they had been fainter, but at Facial they were literally applied with a heavy hand. “This is fresh strawberries,” the attendant would assure me, coating my face in a thick salve which smelled like Pepto-Bismol. Manipulating my chin and cheeks she would promise, “This one today is a refreshing mint.” I was then left alone in a darkened room for 30 minutes, my nostrils packed with so much after-dinner candy.

In the daily half hour which alternated between Hands and Feet, I had my favorite Chasritz woman—but then I had nothing for her to work with. Showing slight freckles through her rosy foundation, talking of canning blackberries until one in the morning, she lifted my feet on Tuesday only to stare in dismay at their scars, calluses, ripped-off toenail. Sinking them into a tub of sudsy water, it was clear she longed to ask, “Bite your toenails?” Defensively, I explained that I was the mother-of-the- bride: “I stood on my feet a lot.” The next day, when it was time for hands, as she plunged my battered, split, dry ones into bowls of warm cream which she massaged into the parched skin, I could see she longed to ask, “Stand on your hands a lot?”

The one place at the Chasritz Salon where I had something to work with and they had an abundance of individual attention to give was my afternoon class called Hair Treatment. The first day I told Evi, the big operator with a blonde wedge cut in charge of me, that I did my own hair. I suspected, as she studied the brittle ends and faded home-dyeing, that this was not a revelation. “We can fix you up,” she promised firmly. And she set about to do so, telling me carefully each time what she was applying and what it was doing. My favorites were an emergency protein pack, correctly called Extreme (dried egg, wheat flour, molasses), and a lighter acid-balanced hair reconditioning treatment which looked and smelled like soy sauce (amino acids and molasses). Our pale green advance letter from The Greenhouse had warned that “you may want to bring a scarf or wig (your hair is in treatment most of the week).” I had assumed this meant we would all spend the week covered in goo; instead, I had fresh clean hair every afternoon, hair which daily grew shinier and more lively. I could see by Tuesday that, if nothing else, I would depart with hair that was twenty years younger.

Some of the other women were not as pleased as I was with this arrangement. They did not like appearing with their hair unset, just as they did not like coming to dinner with their nails unpolished. What was fine for exercise during the day made these women nervous at night. So they used their own heated curlers or wrapped their hair in caftan-matching turbans for the evening’s socializing.

By Wednesday, the fourth day, my most powerful emotion was hunger. The Greenhouse food, which seemed to satisfy everyone else, was for me far too low in protein, and what calories we got came much too late in the day. It was essentially a fat person’s diet: heavy on pseudo-dressings, sauces, and gravies; overgenerous on sweet-tasting desserts; long on pomp and appearance and short on substance.

On Sunday the house doctor—dressed in an aqua leisure suit—had called on us in our rooms to get a medical history—primarily to scout for possible trouble from high blood pressure—and to select our diets for us. There were three options: a 500-calorie plan, a 750- calorie plan, and a maintenance diet of about 2500 calories. I had requested the 500, thinking that if I was going to do this I was going to do it all the way, but found that it required a series of tests and a letter from your home physician. So I settled for the 750 calories. That was what I aimed for in my crash diets at home: I would give myself ten 75-calorie feedings a day of such goodies as shrimp, egg, water-packed tuna, skim milk. It wasn’t so hard.

The Greenhouse’s version, on the other hand, could not have been more excruciating. At seven we received—with our tray, the rosebud, and the Dallas Morning News—one medium poached egg, one paper-thin communion wafer of white toast (or lace doily of raisin toast), and four ounces of juice or fruit. At ten waitresses in eyelet aprons served us, from a poolside cart, a coffee mug of potassium broth, a house specialty designed to replace the minerals our bodies were losing. Potassium broth is made by simmering various root and leafy vegetables for three hours, throwing out the vegetables, and serving the hot water. Calorie count: 0.

Lunch was served at one beside the pool. The midday meal consisted of a mountain of parsley (a closet diuretic designed to leach out pounds of fluid), plus a heap of raw or steamed vegetables which had been diced, sliced, spliced, riced, or iced to make them look like much more than they were, then coated with a sweetish glaze. On the side was our protein: grandson of goldfish (a trout the size of a large sardine) or two-nut-sized lumps of crab. On our best day we had an artichoke stuffed with sliced, spliced baby shrimp. For our second course we had a choice of iced tea or coffee. Our third course, served with suitable delay, was dessert: an eye-catching array of paper-thin orange and lemon slices. “You may have two,” the waitress passing the tray whispered.

Midafternoon we had about three ounces of a variation of the watered fruit frappe, served in paper cups beside the water cooler outside the massage rooms. I saved my lunchtime orange slices to eat at five along with my afternoon glass of tea. It was clear, on this fare, that it was a short trip to becoming a caffeine junkie. I tried to limit myself to two cups of coffee and two glasses of tea. We had unlimited access to either—pick up a house phone in the hair salon or by the pool or in our rooms and either would appear on a tray within minutes. In order not to waterlog on the tea and coffee—which daily became more attractive as hunger became worse—I gobbled up every leafy twig of parsley and sprig of watercress and stayed off the fluid-retaining sugar and salt substitutes.

Dinner, after the “cocktail,” was a seven-course meal, served with the élan and pace of a five-star restaurant. Each night we had a new bouquet of flowers on the table; each night we sat down to a different tinted pastel cloth, a different set of Ceralene or Rosenthal—a robin’s-egg blue cloth, might be laid with deeper blue morning-glory-bordered plates. First course was a clear consommé or other low-calorie soup such as gazpacho. Second course was a salad, usually watercress coated with a thin yogurt-based or gin (it’s their new secret ingredient) and lemon dressing. Third course was a variation of the diced, riced vegetables, again dressed with parsley and arranged in an artful manner so that two blanched asparagus stalks could fill the center of a china plate. Sometimes, for variations in texture and color we might have a mix of two vegetables—two slices of yellow squash and a tablespoon of toasted potato skins. Fourth course was the meat. Because we had fish only once (a lovely poached sole) and never a bird of any feather, the portions of meat were limited to three ounces. Three nights we had crouton of tenderloin; two nights, frail medallions of veal; one, elbow of lamb.

No one seemed to mind the sparseness of our food. Everyone knew, and was proud of the fact, that the beef was deveined and defatted expressly for us in Kansas City. It gave them the old cared-for feeling. Making leisurely conversation between courses, they compared The Greenhouse to other spas. “At Golden Door I think they put you two in a room.” “Oh, really? I’d hate that.” “At Maine Chance they don’t put any ice in the water. Something to do with digestion.” “That sounds awful.”

We talked about the celebrities who came to our spa. The socialite from the East Coast said that on her last visit Princess Grace had been there, too. “She was as nice as anyone could be.” Lady Bird, someone said, was due next week, which was of special interest to those staying on for a second term. A woman at my table had been there with Sissy Farenthold. “I went out of my way to be nice to her, but she took all her meals in her room. She was working on that college, you know, and only came out to exercise.” As they talked I could hear echoes of Aunt Doris’ pleasurable recounting to me of mealtimes: “I love the happy hour first, when we’re just as gay as if we’re having a martini. And then the dinners are wonderful. They don’t hurry you, and, best of all, you don’t have to plan them yourself.”

Fifth course was finger bowl, which took twenty minutes.

Sixth course was the peak of the day, for which the women had waited and sacrificed and anticipated: dessert. It was the day’s reward for work accomplished. (As I said, it was a fat person’s diet.) Airy mousses served with a sauce of pureed raspberries, elaborate molds garnished with leaves and delectable sweetened fruits. Combining sugar, artificial sweetener, egg whites, skim milk, gelatin, and fruit, the kitchen was able to pile each guest’s plate with a ten-ounce confection and still stay within the 750-calorie limit. Those on the maintenance diet got the real things (at lunch and dinner): huge wedges of pecan or cherry pie with whipped cream.

I don’t eat sugar. Besides, I didn’t want to add any more carbohydrate to what was already too much. So I asked for the portion of plain fruit which went to the 500-calorie dieters. I cradled it in my hands through dessert and the seventh-course demitasse until I could take it to my room for a bedtime injection. (One night the evening maid, coming in to turn back my bed, removed my five melon balls and slice of lime. Thereafter I left enormous instructions on the marble counter: DO NOT REMOVE THIS PLATE.

At first I thought if they would only let me get in that kitchen and bring on the cold chicken and skim milk we would all feel better. I could not have been more wrong. Wednesday afternoon when the exercise-exhausted crowd hurried to get the fruit frappe, they found instead three unwanted ounces: “This is milky.” “I hate milk.” “This tastes sour or something.” The same negative reaction met our one lunchtime serving of half a beautiful plumb Cornish game hen. My eyes glazed with recognition and appreciation at the sight of the fowl. The other four women at the wrought-iron table greeted it with dejection. “Ugh.” The Tandy exec poked at hers like a dog at an old rag. “It doesn’t even look cooked,” said another. “Yecch, its cold.” The pale young woman on my right did what any well-reared girl would do—she stuffed the half a chicken under her omnipresent pile of parsley so it would appear to have been eaten.

These guest-pleasing (I was definitely a minority) menus were planned by the legendary Helen Corbitt. The overweight gourmet graced us with her presence one morning for her famous mini-cooking class. Crowded eagerly about her in the kitchen, we watched her dice and slice and splice the vegetables, steam and peel the dessert peach and serve it in a Sweet ’n Low and red wine syrup. In amazement we heard her explain how to cut and fan three ounces of tenderloin, dress it with a gravy of margarine, pan drippings, and gin, add a few vegetables on the side, and serve it to “dumb hubby who’ll think you cooked him a sirloin steak and love you for it.” Before our eyes she cut three green beans on the diagonal, “with a sprinkle of Parmesan cheese for the fat flavor you like,” add parsley and three large broiled split and fanned shrimp, and turn it into an elegant ladies lunch plate.

Even though everyone took copious notes on the low-cal way to cook, it was clear that they had no interest in these fictions and much preferred the creams, butters, sugars, and sauces these dishes were simulating. Corbitt spoke for everyone (and revealed the philosophy behind her menu planning) as she laboriously fluted the edges of a grapefruit for broiling: “It would taste a lot better with bourbon and brown sugar.”

As the week progressed, I got a case of diarrhea, bleeding gums, a sore throat, and screaming nightmares. Once, confronted with no remedy in sight except the jots of honey that the house nurse passed out to those who grew faint after exercise, I lost control and mutinied. It was “cocktail” time in the parlor, and we were making conversation about our day. The young man in dinner jacket brought in a huge crystal vat of the cold boiled shrimp which were our night’s hors d’oeuvres. “You may have two,” he murmured as we crowded around the table to see the elegant treat.

Knowing I was not going to eat my dessert, I calculated that I could have at least half a dozen shrimp and still stay within the allotted calories. Never in my life had anything looked more enticing than the straight shots of cold shelled protein. This was not a decision I intended to have made for me. “I am going to have five,” I told him, and, before the shocked ears and embarrassed eyes of the assembled, I took five shrimp and, sitting on the velvet couch, ate every one.

Wednesday was considered the midweek slump and supper was served on trays in our rooms. Thursday, to lift our spirits, The Greenhouse took us on an excursion into downtown Dallas to Neiman-Marcus. The store had already opened its campaign upon our charge cards with a finesse and style lacking in Chasritz. Tuesday night we had lined up our brocade chairs in two rows to make a runway in the large living room. Three Neiman’s models—a size 6, a size 8, and a size 10, affecting the matronly styles of flowing sleeves, face-covering hats, and loose waistlines of much larger sizes—showed us the best of the coming season. For looking and trying on after the show, a large additional rack held more clothes. Many of these better designer garments were on sale—a $1600 Galanos, say, reduced to $1100. Some of the old regulars purchased on the spot; many left instructions for flowing chiffons to be held for them for a Thursday fitting.

On Thursday afternoon we were checked out into our limousines at The Greenhouse door and checked in again inside the back door of Neiman’s downtown. (Rumor had it that this roll call was because one year a woman had failed to show up when it was time to catch the limo and was discovered a week later in Paris, where she had fled her husband.) Neiman-Marcus welcomed these Thursday afternoon onslaughts of Greenhouse women. All the saleswomen knew that our credit was good. We had but to say, “I’m at The Greenhouse,” and the largest order went through without a question. In the three hours in the store I bought ten high school graduation presents, a plum cotton T-shirt (Italian, $12), and a bottle-green linen skirt (French, $65). On the fifth floor, when I purchased a pair of art deco green earrings ($5), the saleswoman said, “You’re from The Greenhouse, aren’t you? I can always tell by the skin.” Obviously, it was not shoppers like me for whom the trip to town was arranged.

I rode back in the limo with the kind of woman Stanley Marcus had in mind when The Greenhouse was founded. It was the East Coast island hopper from my morning walks. A chunky, cruise-tanned woman with skillfully tinted auburn hair, she had picked up a few things “that I never have time to get at home”: an ivory necklace just perfect for winter lunches in the Caribbean; for a fall trip to Florence, a handful of Italian cottons which were to be fitted next week when she had lost her second term’s pounds. And, most delightful, a set of place mats which just matched the Rosenthal Polygon china in her Brighton Pavilion breakfast room.

“What did you find?” she asked me with interest, as the security guard readmitted us through The Greenhouse doors.

When we were not being exercised, beautified, semi-fed, or pressed to buy, we were being socialized. Every evening except Wednesday we had entertainment in the drawing room after supper. The staff made skillful use of these nighttime shows to capture the dominant moods of the group as the week progressed. For example, at the start of the week—when our mood was still one of the highest hope—they had brought Valere Willard, a mystic, to The Greenhouse parlor.

“I see a powerful aura there,” the mystic said. All our eyes followed her gaze, which was riveted on one of the Russians. “I see a powerful purple aura there. All of you have auras.” Some of us shifted nervously in our chairs. The Chinese woman remained immobile, staring back. She did not have to be reminded of her powers. “You can become more than you are,” Willard promised us. “You can learn to use your powers to expand your life.” She also read palms—for $25 a person, in specially scheduled sessions.

The art dealer and I talked later to a Virginia plantation owner named Kaye Ann who had forked over the money for a glimpse at her future. She was somewhat disappointed. “She’s amazing, honestly,” she insisted, talking loudly and nonstop, punctuating the air for emphasis, “She knew things about my son that nobody else knows. She told me things I never told anyone but my husband. But she didn’t tell me anything about me that I didn’t already know.” She paused to adjust an outsized checked-gingham hat. “She told me I had a lot of energy I was just starting to use. She said I had a lot of potential that I hadn’t tapped. But anybody can see that. Why last year I gave a little old surprise birthday party for my daddy. Three hundred people to a sit-down dinner. I smoked my own turkeys in our pits and roasted my own beef tenders and filled my six-foot walk-in cooler with bacon-wrapped chicken livers. I even lined the walls of the dining hall with blowups of daddy—he’s a bottling executive—at every stage in his life and with every grandchild. Why it took ten men twenty hours each just to smooth out the Dr Pepper cans we used for napkin rings.” She stared at her unrevealing palms. “Why anybody can see I have energy. But what am I going to do with it?”

At the start of the week we had shrugged off such questions. Back then we were each reacting to the other as the stereotype of what we had expected to find at The Greenhouse. But by Friday we had relaxed enough to realize that inside the green and pink walls, like outside, no one is quite what she seems. Our major socializing became not the evening programs but our tea groups around the pool after classes.

Betty, the natural hostess of “our salon,” was able to say to Kaye Ann in her ever-changing pink-, green-, and orange-checked gingham engineer’s hats, “You don’t have to spend your life giving sit-down dinners for three hundred people.”

We found out that all of us who ordered iced tea together had paid our own way for the extravagant week; that none of us lived in “families”: the Tandy exec and the lawyer had never married; the art dealer was divorced; Betty was widowed; Kaye Ann and I had sent our last children off to school.

Earlier in the week, with our guard up, we had swapped the legends which abound in health spas. Betty told the story of one guest who had sneaked into the kitchen and devoured 99 dollars’ worth of caviar, another who had eaten the green leaves off the plants in her room. A tale made the rounds that a group of ranchers had come and partied all night, leaving whiskey bottles floating in the pool with messages which said, “Wish you were here.” Someone had heard that four prostitutes had stayed a week, in Bergdorf finery, at the expense of their gentlemen friends.

But by the end of the week, when the advertising manager had quit smoking and the lawyer’s feet had healed, we could share stories about ourselves. Betty talked to me about her daughter who was studying writing. “She wouldn’t be caught dead at The Greenhouse. She lives in an old farmhouse, right down to the chickens. I have to sweep the chicken shit off the porch every time I go see her.”

We made a few confessions. The Tandy exec admitted to me that on our early-morning walk, when I had said I wrote, she thought I had made it up. “You know, I thought you just wanted to have something different to say.”

We discovered that the shy woman perpetually in sunglasses had been in a train-car wreck, had lost the use of one eye, had gained 80 pounds after surgery, and then, painstakingly, with the help of Weight Watchers, had lost all 80 again. She had come to The Greenhouse to take her first step back into the world.

Although to me it seemed a cloister, to many of the women who came there, The Greenhouse was the outside world. Having grown up in a culture that was insular, this was the one place permissible to get away from husband, home, or family for a week or two.

Our last night of programmed socializing was bingo. It too captured the class mood after the final day of reckoning at Weigh and Measure. We stood in line on Saturday morning in our blue leotards and tights for the last time, queuing up to the scale and tape measure in the dance studio. While one instructor weighed and then measured us—delicately calling only the last numbers, so that, from top to bottom, she might say, “Seven,” “Six,” “Eight”—a second wrote down the translation of our successes and failures on our green, rose-embossed “diplomas.”

There was not much tension in the line; most of us had slipped into the room before breakfast to prepare ourselves for what had or had not happened. Those who knew they had lost nothing or the standard two pounds had expected as much. As Aunt Doris had assured me, the weight loss was not the main point. “I always come home mentally and spiritually refreshed.”

Many had not seriously tried. One woman confessed that she had eaten a cheese sandwich in the Neiman’s tearoom; had bought and consumed a pound of Godiva chocolates; and had polished off the medicinal martini she brought from home in a lotion bottle. Many used the loss of just two pounds to justify their longtime failure to be anything but fat. The reasoning went: “If that’s all I can lose on The Greenhouse’s stringent routine, how can I be expected to lose at home?” The alcohol-attached woman I had eaten with the first night had proved to herself that there was, after all, no benefit to drying out: “If that’s all I’m going to lose, hell, I might as well have had a drink at bedtime and got some sleep.”

The instructors made soothing promises to these women: “You’ll see, by Tuesday morning you’ll have dropped another two pounds.” Those of us who knew what it took to move even one inch or pound and had paid our dues in full, had fine success. The art dealer had lost her wine belly and five pounds from her small frame. The gum-chewing lawyer had lost five. I had lost not only four and a half, but an incredible eight inches (that’s $172.50 an inch), including two from my waist and two and a half from my abdomen. If they had measured me elsewhere, I would have lost even more, as my ankles were thinner (from all that parsley and watercress) than they had been since the days when their only function was to hold up ankle bracelets. I had to move my sandal straps over two notches so they wouldn’t fall off.

For dinner that night we were petted and pampered and coddled for the last time. Everyone wore her best caftan. The mood at bingo was the farewell mood: If not this hand then next time I’ll win a Helen Corbitt cookbook or a Toni Beck tape. Next time I’ll get a better card . . . Next year I’ll come back and lose more than I did this year. If not this time, then next time I’ll get lucky. It’s all in the cards; it’s not anything I have control over.

My feeling was that passivity had been a nice place to visit but I was ready to go home. When director Wood called out “B-6” and “G-44” and I went up to select my prize, it seemed a high price to pay for a free cookbook.