This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In the back seat of my rental car, Farrah Fawcett began taking off her clothes. “You’re not going to look, are you?” she said, giggling like a teenager.

“Oh, no,” I replied from the driver’s seat.

“I bet you can see me through those little side mirrors,” she said, her words nearly muffled by the sound of zippers and the rustle of cotton.

“Oh, no,” I said, my fingers involuntarily clenching the steering wheel. “Oh, no, no, no.”

It was early evening in Los Angeles—the setting sun was spreading across the sky like a great cracked egg—and there I was, chauffeuring around the ultimate Texas bombshell and the foremost sex symbol of my youth. I had no idea where we were going; all she would say was that she wanted to take me on an adventure. “Get ready,” James Orr, who directed her in the 1995 comedy Man of the House, had warned me. “She is charming beyond comprehension. She’ll completely take control of you.” “I don’t know what it is about her,” added her best friend, Nacogdoches native Alana Stewart, the ex-wife of George Hamilton and Rod Stewart. “But she still has this ability to make all of you guys simply giddy.”

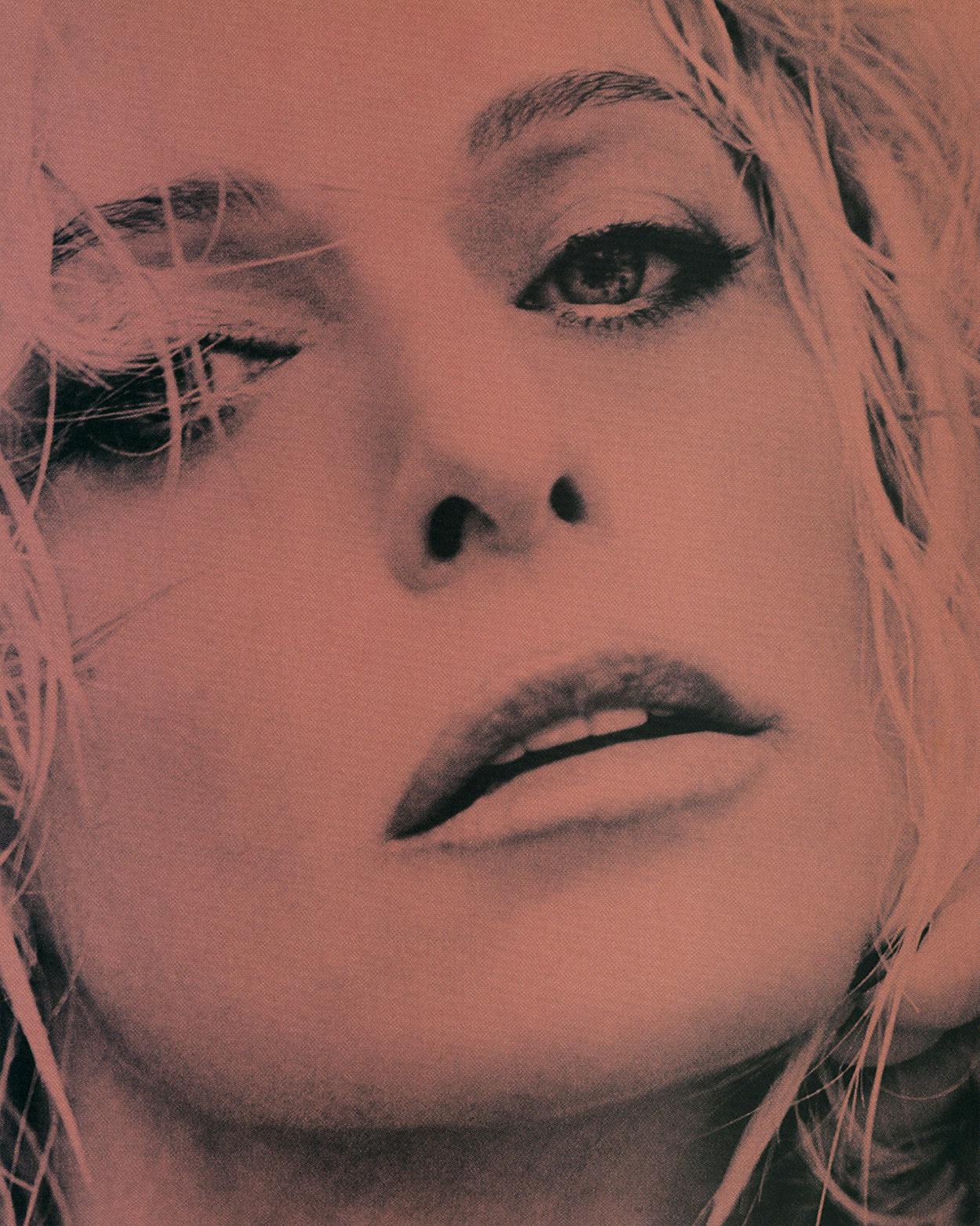

Of all the great beauties who’ve come out of Texas, Farrah Fawcett stands in a class of her own—even at fifty, a milestone she reaches the first week of February. She remains so much a fixture in the public imagination that all you have to do is mention her first name and everyone knows who you’re talking about. By all rights, she should be the kind of nostalgia-addled celebrity who is the answer to a trivia question: Other than a single season on the TV show Charlie’s Angels back in 1976, her claims to fame have been, more or less in order, a poster she posed for in a bathing suit; a smattering of made-for-TV movies; a disastrous sitcom, Good Sports, that also starred her longtime boyfriend, Ryan O’Neal; and a few, well, estimable feature films. Yet her mystique only seems to grow. The December 1995 Playboy, which featured recent topless photos of Farrah, was one of the magazine’s biggest selling issues ever. As recently as last November, the august New York Times declared that Farrah had the most famous hair of the seventies—and maybe of all time: “Her feathered, high-lighted, layered phenomenon was a work of art that looked as if it had just come out of the sea and had been tossed by the wind into a state of careless perfection. Farrah hair was emblematic of women in the first stage of liberation—strong, confident and joyous—before the reality of mortgage payments and single parenthood set in.”

What was that again? Careless perfection? First stage of liberation? What is it about Farrah that robs just about everyone of his senses? And why does she remain such a force in American pop culture? The haircut worn by Friends star Jennifer Aniston was all the rage for exactly one TV season, whereas in malls and small towns across America, you still find women with Farrah hair. And why do men continue to be haunted by her allure? Last fall, at a party at the Governor’s Mansion following a University of Texas football game, I started asking about Farrah. Within minutes, there were eight guys around me swapping stories. When I mentioned that I was going to see her, their mouths dropped open like choirboys hitting high notes.

Actually, when I flew to Los Angeles, I wasn’t sure that I would get the chance to spend more than a few minutes with her. Her publicists—efficient women all, with voices frosty enough to chill the air—had advised me that Farrah was quite busy but perhaps would have time to meet me for a drink. They instructed me to check into the romantic Hotel Bel-Air, where rooms start at $325 a night. If time permitted, I was told, she would descend from her mansion, which is hidden in the hills above Sunset Boulevard, and grant me an audience at the hotel’s bar. Farrah has given few interviews in the past decade, and even then she speaks in only the vaguest terms about her life, including her fifteen-year relationship with O’Neal and their son, Redmond, who is now eleven. Personally and professionally, she prefers to stay out of the spotlight. Although TV executives beg her to act in their networks’ movies—a few years ago, when NBC president Warren Littlefield read a script he thought Farrah would like, he drove to her house and hand delivered it—she sometimes takes off nearly two years at a time.

Hollywood, of course, doesn’t quite know how to regard such an enigma, and the tabloids constantly suggest that dark things are taking place in her life. They’ve printed unconfirmed rumors that O’Neal beats her. They’ve published photos purporting to show horrific cottage-cheeselike lumps on her legs. They’ve alleged that she is a demanding diva who once spent $3,700 a week on a movie set for hair conditioner. “What’s amazing to me is that, after all her years of being famous here, very few people know much about her,” said her agent, Todd Harris of the William Morris Agency. “It’s almost as if no one can ever get past that hair and that smile. If only people knew what she was really like.”

As I sat in my hotel room, waiting for Farrah’s call, I doubted I would get to find out. She is always cautious around strangers, I had been told. She’ll never open up to a reporter. Then, at around four-thirty, the phone rang. “Oh, hi,” she cooed in a dovelike voice. She was in her car. “I’m headed that way.”

To understand the particularly singular nature of Farrah’s fame, consider her in context. She came of age in the mid-seventies, one of the silliest periods in American cultural history—it was the era of the Bee Gees, Saturday Night Fever, WIN (“Whip Inflation Now”) buttons, and in 1976, the year of our nation’s bicentennial, Charlie’s Angels, an hourlong ABC drama centered on three young female detectives in revealing outfits. Time magazine called the show “aesthetically ridiculous” but “commercially brilliant.” In an ABC survey two thirds of those polled rated it as their favorite TV show. The Angels—Farrah and Kate Jackson and Houston’s Jaclyn Smith—received 20,000 fan letters a week from both men and women.

Although Farrah had few previous acting credits and apparently fewer undergarments (her character, Jill Munroe, rarely wore a bra), she became an international sensation. Her poster—hair, smile, red one-piece bathing suit—sold 12 million copies, more than any poster in history. No other, not Marilyn Monroe’s, not even the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders’, has sold so well. Looking at photos of Farrah back then, however, you’d find it hard to fathom her popularity. She was certainly pretty, with flawless skin and an anatomically correct Barbie-doll body. But even Farrah herself has admitted that there were lovelier girls in Hollywood, including Alana Stewart, who was breaking in at the same time. Farrah looked more like a sexy cheerleader than she did a starlet. So why did she become the symbolic standard of blond beauty? And why, after she quit Charlie’s Angels in an almost comical snit after only 22 shows—in one interview, she said that the producers were preventing her from “growing” as an actress—didn’t she disappear like so many other “it” girls? Why were we so fascinated by her marriage to Lee Majors, the stunningly wooden star of The Six Million Dollar Man, and why were we equally fascinated when she dumped Majors for O’Neal, the movie star–pugilist?

To her credit, Farrah valiantly attempted to prove herself as an actress. In 1983 she moved to New York to appear in a small Off-Broadway production called Extremities and received laudatory reviews for her portrayal of a woman attacked in her home by a sadistic rapist. She practically invented the imperiled-woman-of-the-week TV movie with her role in 1984’s The Burning Bed, in which she set her abusive husband on fire as he slept. And while her big-screen career has so far been abysmal—the joke in Hollywood was that one of her feature films, Somebody Killed Her Husband should have been titled Somebody Killed Her Career—she manages to get the occasional interesting role. Last year, for instance, acclaimed actor Robert Duvall asked Farrah to co-star in an independent feature film he’s directing, The Apostle E.F., which is about a Texas Pentecostal preacher who escapes to Louisiana after accidentally killing his wife’s lover. Confounding his comrades in Hollywood, Duvall asked Farrah to play the sought-after role of his wife.

“Farrah Fawcett?” I asked Duvall when I reached him by phone. “Of all the actresses who would kill to be in a movie with you, why did you pick her?”

“Do you know what the hell you’re talking about?” Duvall snapped. “That woman’s work has been very underrated. I’m serious, now: You go look at some of Farrah’s work in those TV movies, like the one where she kills her children [Small Sacrifices]. That woman knows how to act. So I don’t have to apologize for a thing.” Before hanging up, Duvall told me that he had spent fifteen years trying to get The Apostle E.F. made. “And let me tell you, it’s a project very close to my heart. I didn’t just pick people out of thin air to be in this. What are you trying to do—mess with my mind?”

Unbelievable, I thought. Here was this serious figure in Hollywood and he’s just as bowled over by Farrah as I am. How can the woman have such staying power?

When Farrah was voted one of UT’s most beautiful women, her reputation spread throughout the state. Guys from other Texas colleges would take weekend trips to Austin on the chance they’d see her emerge from the Tri Delt house.

When I showed up at the Hotel Bel-Air bar fifteen minutes before Farrah was due to arrive, a grim waiter took one look at my denim shirt and handed me an oversized white blazer with a red wine stain over the heart. “Coats are required, sir,” he said.

I sat down at a table in the corner and waited . . . and waited.

An hour and a half later, she came through the door looking left and right. She had her sunglasses on even though the bar was dark enough to hide a herd of cattle. She was wearing black motorcycle boots, a black miniskirt that revealed aerobicized, lump-free thighs, and a black T-shirt that could have been painted on. Her famous tresses were going in about thirty directions. She seemed impossibly tiny—you could have counted all her ribs—and her skin was so translucent it was pale. Other patrons of the bar—rich and powerful people who you’d think were accustomed to seeing celebrities—made pathetic attempts to act uninterested in her. But every head twitched as she walked toward my table. Clearly, a Farrah Fawcett sighting was still buzzworthy in this town. “Hello, how are you?” she said, pulling off her sunglasses as she sat down next to me. I assumed she would be reserved, the kind of star who carefully chose her words. But before I could say hello back, she started rotating her head in a slow, circular motion until her neck made a popping noise. “There, now I’m comfortable,” she said, raising her eyebrows suggestively. And then, like a curtain pulling back in a theater to reveal a brilliantly lit stage, she opened her mouth and smiled.

We had known each other for less than two minutes, and the seduction was already beginning.

She had to have sensed early on—perhaps as far back as her childhood in Corpus Christi—that she was a golden girl. Her mother, Pauline Fawcett, once said that when she carried Farrah to the grocery store, women would stop their carts and say, “She looks like an a-n-g-e-l.” Other kids in the neighborhood came by the house just to look at her. “I always felt so self-conscious,” Farrah told me. “I wanted people not to look at me because so many people kept looking at me.”

Before long, Farrah Leni Fawcett—people are astonished to learn that her name was invented not by Hollywood but by her mother—was dating the most popular boys and winning her high school’s beauty contests. And from the day she set foot on the UT-Austin campus, she drove young men mad—and none madder than Greg Lott, a dark-eyed sophomore quarterback who had come to play for Darrell Royal when the Longhorns ruled the NCAA. The story of what happened to his life because of Farrah is almost as legendary as the story of what happened to Farrah. To UT alums from the mid-sixties, Lott is a mythic figure: He was the Texas boy who had nearly corralled the great Farrah only to destroy himself in the process.

When I called Lott, I fully expected him to say he had no desire to talk about his past. Now 51, he runs a small flooring-and-design company outside Austin and prefers to live a quiet life: He has never given an interview about his days with Farrah. But when I told him I was attempting to explain her allure, he chuckled and agreed to meet me for lunch.

“In the fall of 1965 we were in two-a-day practices,” he told me, “and the word started spreading through the huddles about this new freshman at the Tri Delt house. So me and a buddy who played linebacker threw on our clothes between practices and ran over to the house to get a look at her.” In those days the girls who pledged Delta Delta Delta were shown off at the start of the school year to the fraternity boys. The pledges stood in a straight line, and the fraternity boys asked the ones they liked to various parties. “We showed up right when all this was happening,” said Lott, “and there were about fifty to sixty pledges in the back yard. A few guys were standing in line to meet one girl, and a few guys were standing in line to meet another girl. And then—I swear to God—there was this line of guys going out the back yard and then around the block. All of them were waiting to meet Farrah.”

No one had ever seen such a sight. She had platinum-dyed hair shaped in the classic bouffant style, and she was wearing a sleeveless minidress—“The kind we had only seen on models like Twiggy in magazines,” said Lott. Utterly smitten, he walked straight up to her—“Football players at UT didn’t wait in line for anything,” he said—but when he finally got a chance to talk to her, she told him that she already had dates for the rest of the year. “It was true,” Farrah told me. “I had been asked out every weekend for the next four months. Dinners, lunches, breakfasts, brunches. Oh, I was so stupid. I thought I was supposed to go out with all of those guys.”

Here’s a philosophical question to ponder: If an eighteen-year-old Farrah showed up at UT today, would she be treated the same way? According to one school of thought, Farrah would be just another sexy blonde on a campus where chic fashions are everywhere and Playboy photographs naked coeds every couple of years. On the other hand, say Lott and others who knew her, Farrah was unique. She was like a frisky palomino, all legs and teeth and spirit. She danced barefoot at a Phi Gamma Delta fraternity party while other sorority girls watched in appalled fascination. She wore cutoffs to art class. And most important, she knew how to mix it up with the boys. “She was a guy’s gal,” said Lott, who finally got a date with her at the end of her freshman year. “She’d stand in the middle of a room at a fraternity party and talk to some guy, and even if she didn’t even know his name, he’d walk away believing that she really, really liked him.”

When Farrah was voted one of UT’s ten most beautiful women—an unheard-of honor for a freshman—her reputation spread throughout the state. Guys from other Texas colleges would take weekend trips to Austin on the chance they would see her emerge from the Tri Delt house. After a night of drinking, they would call the house, hoping to get her on the phone. A few years ago, actor Peter Weller, who in the mid-sixties was a thin, no-name drama student at North Texas State University in Denton, told Farrah that he was walking along the beach one spring break at Padre Island when he spotted several young men surrounding a blonde sitting on a convertible. Weller heard another person say, “That’s Farrah Fawcett over there”—and he headed for the car.

One enduring rumor about Farrah’s pre-Hollywood life was that the Tri Delts kicked her out after she was caught having sex in the shower at the sorority house. Farrah said such an incident never happened. She quit Tri Delt, she told me, because she was tired of jealous sorority leaders telling her what to do and who to go out with. Moreover, she said, compared with the other girls, she had different tastes in everything from shorter skirts to art. (Under the tutelage of Professor Charles Umlauf, she became a dedicated sculptor and painter, concentrating on female nudes.) “If you believe everything that was said about me during my college years, then I slept with lots of people I never even met,” she said. “It’s one of the things I really regret—being so famous at the University of Texas, having no control over the gossip, having no privacy.”

Whatever the case, it’s true that during her sophomore and junior years, Farrah dated only Lott. They were the most glamorous couple on campus: Lott with his infectious grin, Farrah with her blond hair. But in his junior year, Lott’s football career ended on a single play, when a University of Arkansas defender hit him from behind, tearing the ligaments in his knee. Then, in the summer of 1968, at the end of her junior year, Farrah moved to Los Angeles. Hollywood publicist David Mirisch had been trying to lure her there ever since she was named one of UT’s most beautiful girls, and she finally decided to give it a try. By the end of her second week in town, she had signed with an agent and had met another former college football star, Lee Majors.

Lott made a few futile trips to California to try to win Farrah back, yet her life was headed in a different direction. She began to get cast in commercials, the most famous of which, for Mercury Cougar, showed her rising up out of a dark sea. She also landed bit roles on TV shows; for her first, on The Flying Nun, she wore a sailor blouse and flirted with a casino owner. (“Soon, we’ll go out to sea,” the owner told her. “Out to see what?” Farrah asked with a giggle.) “You could just look at her and tell that she was a lot of fun,” says Alana Stewart, who competed with her for roles. “And she had this great knack for conveying that on screen.”

In 1973 she and Majors—“The Right Fluff,” one writer called them—were married in a ceremony at the Hotel Bel-Air. Meanwhile, Lott dropped out of sight. He was supposedly spotted a few times among the hippies who were beginning to populate Guadalupe Street adjacent to the UT campus. His former Longhorn teammates heard that he had grown his hair long and was peddling dope. Indeed, not long after Farrah made her name on Charlie’s Angels, Lott was arrested while driving a truckload of marijuana from Arizona to New York and served a year in federal prison.

The legend of Lott grew even bigger in the late seventies when he cleaned himself up and briefly reconnected with Farrah while she and Majors were separated. Lott even went to see her in Acapulco while she was filming the 1979 movie Sunburn. But then Majors resurfaced and won her back. A defeated Lott returned to East Texas and took a job with an oil company. Eventually, his bad habits returned too. In 1982 he was busted on a federal cocaine charge and imprisoned for three years.

Today Lott says he has been sober for nearly a decade. After his release from federal prison, he worked as a drug counselor with inmates in a state penitentiary. Seven years ago, he married a woman he had met in a twelve-step program. He is still big and handsome, with his silver-streaked hair brushed back and a UT ring on his right hand. And he still has that protective tone in his voice that all men use when they talk about their first loves; he told me, for example, that Lee Majors was “one bad hombre.” He also told me that he had last seen Farrah in 1995, when she asked him and his wife to a charity benefit in Corpus Christi where she was being honored. In the crowded ballroom, Lott and Farrah, who had barely seen each other in seventeen years, spoke only for a few minutes. “Ryan O’Neal was there,” said Lott, “and let’s face it, he is not the most comfortable guy for an ex-boyfriend to be around.”

I delicately asked Lott if he felt his obsession with Farrah had led to his downfall. “Well, you could say my college life pretty much disintegrated,” he said. “But no—heck no. I think I was rebellious because my football career ended so quickly. I hadn’t prepared for a life after football, so I started drinking, I got involved with drugs, and I just dropped out.”

Lott flashed me a look. “But I’ll tell you, she could wrap you around her little finger and make you think about nothing else but her. I’m not saying she did it on purpose. She was the sweetest girl you could meet. She just had an aura. Listen, my wife’s niece is a Tri Delt pledge at UT, and she asked me the other day, ‘Is it true Farrah was caught having sex in the shower at the sorority house?’ I couldn’t believe it. Here we are, thirty years later, and girls who’ve never seen Charlie’s Angels are talking about her.”

It was clear from the moment I began my interview with Farrah that I was in the presence of a master. I started to ask a question, but she was staring at me. Finally, I realized what she was looking at: my jacket!

“They made me wear it,” I said.

She leaned over and fingered the material. “Actually, it’s not bad on you,” she said.

Usually the celebrity interview is one of life’s most superficial encounters. In the hour or so they spend together, the reporter tries to ask questions the celebrity hasn’t answered a thousand times already, and the celebrity tries to say something interesting so the public will continue to care. I had assumed my time with Farrah would be no different. But after thirty years of being hounded by the media—she once said that all she had to do to get on the cover of People was to “have a new boyfriend or even a new dog”—she knew exactly what to do. For the first 45 minutes of our interview, she sipped hot tea and mused on everything from her workout regimen (yoga, tennis, paddle tennis, squash, racquetball, and 175 sit-ups a day) to her “difference of opinion” with her neighbor, Wilt Chamberlain, over the shed behind her house that she uses as an art studio. “He says I built my art shack—that’s what I call it—without a permit,” Farrah said in a cute but indignant way. “I wanted to say, ‘You know, Wilt, during those years when all those girls were ringing my doorbell by mistake asking for you, did I complain?’ ” She then told me how certain movie producers were “nitwits” and launched into a description of her teacher from her Catholic elementary school, Sister Philomena, who had beautiful skin. “What is it about nuns and their flawless complexions?” she asked.

She was like a great first date: magnificently flirtatious and slightly unpredictable, an enthusiastic talker who told entertaining stories about herself even if they had no particular point. “What people don’t know about Farrah is that she’s very straightforward and very real,” says Alana Stewart. “She loves to tell you exactly what’s on her mind. We’ll spend an evening painting our toenails, leafing through fashion magazines, and gossiping, just like we’re girls again.” Indeed, Farrah seems to have hardly aged. Perhaps that’s why she did her much ballyhooed Playboy layout—not only because she “wanted to show the female body as an art form,” as she told me, but also because she wanted the world to see that even at fifty, she still looks as good as Jenny McCarthy and other Generation X Farrahs.

At some point in our conversation, I finally got to ask Farrah about her appeal: What could have possibly caused an entire society to adore her, ridicule her, and mob her every place she went? To my surprise, she couldn’t explain it, either. “But it’s something I can’t escape,” she admitted. “I was in Houston recently visiting my parents, and we went to one of those chicken-fried-steak restaurants. Redmond and I had just been Rollerblading. I was wearing no makeup, and I hadn’t done anything to my hair, and this one-hundred-and-seventy-five-pound woman came up to me and shouted, ‘Farrah, how can you let yourself go like this? You are Farrah Fawcett!’ Then she asked me to sign an autograph because Charlie’s Angels had been her favorite show. I thought, ‘Sometimes it isn’t worth it. The fame is just not worth it.’ ”

Maybe it was that story that turned the switch. Or maybe it was because our conversation about UT had gotten her thinking again about her carefree coed days. Whatever the reason, after an hour of sitting in the bar, she decided to show the side of herself that had entranced Greg Lott, Lee Majors, Ryan O’Neal, and countless others. She leaned her head in, gave me a lingering stare, and then said with a little giggle, as her tongue darted between her teeth, “Would you like to go on an adventure?”

I felt my mouth go dry. “An adventure?”

“Well, um, yeah,” she said softly, and then she opened her mouth and hit me again with the smile, the one from the poster, the one that suggested that as innocent as she looked, she knew how to do a whole lot more. “Maybe we should have a shot of tequila before we go,” she said as she motioned for the waiter to come over.

She sipped the first half of her shot like a lady, downed the remainder in one quick gulp, and then took a lime and licked it—slowly. I felt exactly like one of those guys at the UT fraternity parties: The prettiest girl in the room was acting interested in me. Suddenly we were on our feet. I tossed my wine-stained jacket at the waiter, and as we exited the door, I think I said, “Hey, we’re out of here!”

The valets in the hotel parking lot flashed Farrah kiss-ass smiles, and one began heading for her car—a green two-door Jaguar with personalized license plates that say BOOM. But Farrah abruptly said, “Do you mind if we take your car?” While the suddenly curious valets pulled up my plain red rental car, she retrieved a large gym bag out of her Jaguar. When a valet opened the front passenger door for her, she said, “I’ll sit in the back.”

I shrugged at the valets, acting as if this sort of thing happened to me all the time. Maybe, I thought, Farrah was accustomed to being chauffeured around. Fine with me. It was only a couple of minutes later that she informed me that she was sitting in the back seat so she could change her clothes. “I need to look different for our adventure,” she said.

For a moment, I could not help but marvel that I had gotten myself into this position. My teenage dreams were coming true: Farrah Fawcett was half-naked in my back seat. But, God’s truth, I never looked. I was having enough trouble getting us to our destination. Reading from a sheet of directions that had been typed up for her, she said, just as I settled into the far left lane of the freeway, “Here, take the next exit.” I looked to the right, but I couldn’t find an opening. The sight of a blonde writhing around in my back seat had apparently caused other drivers to slow down beside me.

“Right here,” she said again, as if I hadn’t heard her the first time.

“I’m not going to make it,” I whined.

Farrah leaned forward. I could feel two soft streams of breath from her nostrils against the back of my neck. Then, using the kittenlike voice that has mesmerized men for decades, she whispered, “Go for it.”

I thought about something that director James Orr had told me: “Farrah has the quality of seduction. I’m not just talking about some cheesy physical seduction. Any woman can do that. But Farrah draws you in, a little at a time, until, in spite of yourself, you’ll do anything she wants.”

Sure enough, I slammed down on the gas pedal, swung the wheel to the right, cut across two lanes of traffic, and raced up the exit ramp like a bat out of hell.

“Oooh,” said Farrah, leaning back in her seat.

We drove east for a few miles until we hit a run-down neighborhood. Farrah consulted her directions. She still wouldn’t tell me where we were going. Hopelessly lost, we cruised the streets like two desperate junkies in search of a crack dealer.

Finally, she saw it. “There, that church,” she said.

A church? This would be our adventure?

“It’s for the Robert Duvall movie,” she explained. “As part of my research, I need to watch a church choir rehearsal.”

I couldn’t wait to see what outfit Farrah had put on. She emerged from the back seat wearing blue jeans that rode down so low on her hips I could see the top of her underwear. She was wearing the same skintight shirt, but she had added a black baseball cap, worn backward, apparently in an attempt to hide her hair and make herself inconspicuous. And she had pulled a video camera out of her bag. “To record my research,” she said.

Then she started wobbling toward the church: The tequila, it seemed, was taking its toll on her petite body. After we entered through a side door, she touched my arm and said, “Um, will you make up something about why we’re here?”

“They don’t know we’re coming?”

“Well, I only had my office call and say a ‘Jane’ wanted to watch choir rehearsal.”

She giggled again as a large woman headed our way, and as I explained to her that “Jane” and I were documentary producers working on a PBS special about religion, Farrah wandered around the sanctuary, filming everything in sight in jerky, film noir movements. At one point, she planted herself by the organist, shooting his feet as they touched the pedals.

“What the heck are you doing?” I whispered.

“I have to play the organ in the movie. I need to know how I should look.” She started giggling again.

I was amazed that the members of the choir didn’t recognize her. As they belted out lyrics about something “washed in the blood,” Farrah did some close-ups and walked to the back of the church, bumping loudly against a pew in the process. When I caught up with her, she was already on her cell phone. “Ryan,” she squealed, “you’re not going to believe this.” She held the phone up so that O’Neal, back home in Beverly Hills, could hear the choir. Then she told him to hand the phone to Redmond so he could listen.

“Can I ask one thing?” I said, remembering the tabloid stories about O’Neal’s jealous temper. “It doesn’t bother him that you’re out with me tonight, does it?”

“Um, I don’t think so,” she said with yet another smile.

“He knows I’m with you, doesn’t he?” I said nervously.

“Um, I think he does.” And then she elbowed me in the arm and headed back toward the choir.

An hour later, when we pulled up to the Bel-Air, the valets rushed to greet Farrah, only to come to a dead stop when they realized she had changed clothes. Awestruck, they turned to look at me, and I could practically hear what they were thinking: What have you been doing with Farrah? I shrugged and handed them my keys. I knew I would never again feel such a sense of power over other men.

For thirty more minutes, we sat outside on a bench. She told me that as she neared fifty, she felt better than she ever had in her life. She said that despite the rumors that her relationship with O’Neal was (to use a Hollywood phrase) in turnaround, they were still happy together. “With me, he met his match,” she said. “Don’t you think so?” She told me she loved being a mother, and that if she never acted again, that would be fine, because there were so many other things to do. “I could spend the rest of my days painting and sculpting in my art shack,” she said. “I’d love for you to come see it sometime.” I knew, of course, that I never would.

As I walked her back to the parking lot, she quoted her favorite saying. “I think it’s from Shakespeare, maybe Antony and Cleopatra,” she said. “It goes, ‘Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety.’ Isn’t that beautiful? That’s what I want my life to be.” There was no question that Farrah knew exactly what she was doing. She has always been aware of the effect she has on men. Even today, at fifty, she has this great way of taking you back somewhere, of capturing all the themes of youth. She is the last link to a certain kind of past.

This time, the valets gave us a respectful distance. She pressed her cheek against mine, climbed into her Jaguar, and left. A slight breeze—just like a wind created in a movie by one of those wind machines—skittered leaves down the street, pushing them against my pant cuffs.

Ten minutes later, I was back in my hotel room and the phone rang. It was her. Her voice was breathy, mystical. “Skip,” she murmured, “I’ve been thinking about it. I’m going to turn the car around and come back to see you. What’s your room number?”

The silence must have lasted for fifteen seconds. Finally, I asked, “Are you serious?”

As her Jaguar climbed higher into the hills above Sunset Boulevard, static began to interfere with the transmission from her cell phone. Her voice was fading. Still, I was able to hear that unforgettable giggle.

“Just kidding,” Farrah trilled. “But tonight was a lot of fun, wasn’t it?”

And then the line went dead.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Farrah Fawcett

- Corpus Christi