Mexico, ever the paradise of calamities. In antiquity, the peoples of that beautiful tierra endured earthquakes, floods, droughts, and other natural disasters. They witnessed the rise and fall of myriad civilizations, several of which created elaborate blood rituals aimed at forestalling still greater calamity, only to see mayhem loosed upon their world, after the arrival of emissaries from a distant land bearing a god their expansive mythologies had never imagined. These stories are obsessively told, over and over again, in the codices, lienzos, and mapas of ancient Mexico.

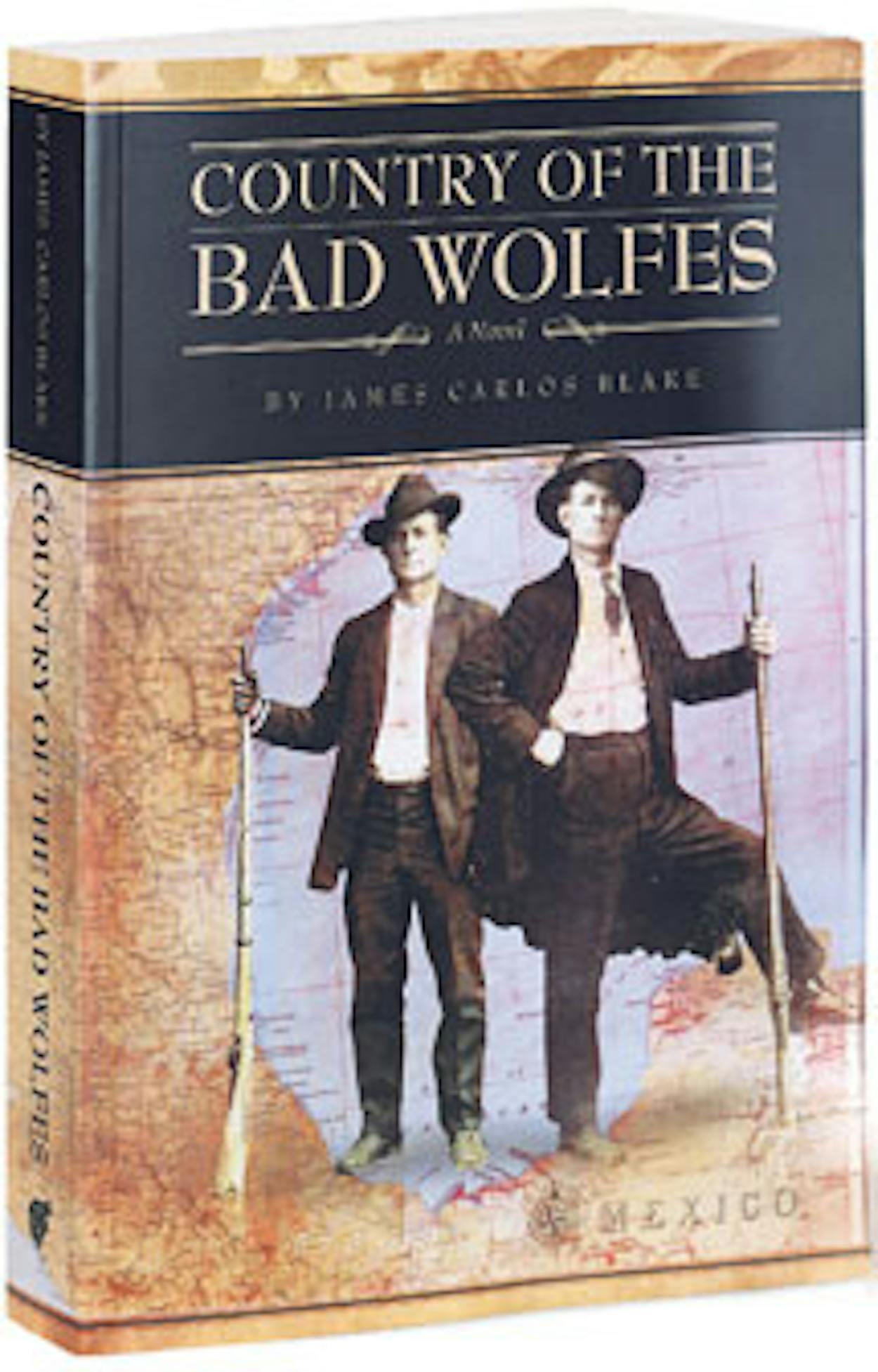

This tragic legacy is intimately reimagined in Texas author James Carlos Blake’s boisterous tenth novel, Country of the Bad Wolfes (Cinco Puntos Press, $16.95), which patiently unspools an epic filial tale, detailing the confluence of Mexico’s ill-starred destiny with the fate of an Irish-British-American family so thoroughly accursed that it seems almost inevitable that the clan should become Mexican.

And so it does, over a century of romance, murder, war, and revolution. Very Mexican.

The novel’s multigenerational saga follows the descendants of Roger Blake Wolfe, a prodigal pirate born in London in 1797 and later forced to flee the law to America. After fathering twins during a brief layover in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Wolfe hastens to Veracruz to resume his nefarious enterprises, whereupon he’s soon apprehended, convicted, and dispatched to eternity by a flurry of bullets from a Mexican firing squad. The book soon shifts to the mid-nineteenth century, when Wolfe’s sons, John Roger and Samuel Thomas, find their way from Portsmouth to Mexico, eventually becoming patriarchs of a raucous mestizo progeny in Veracruz and Mexico City, respectively. John Roger fathers the novel’s second, almost feral pair of twins, James Sebastián and Blake Cortéz, who emerge from the swirling cast of Wolfe family members as the tale’s true stars. These brothers are natural pirates, skilled crocodile hunters, legally immunized border assassins, and lovers of Mexico—and of the Mexican woman who was their wet nurse. They eventually settle in Brownsville, in the first decade of the twentieth century, and become much-feared enforcer lieutenants for the Texas border baron Jim Wells. Seemingly unperturbed by the darker undercurrents of their family legacy, they bring a devilish glee to the violence they perpetrate.

Throughout, plotlines involving the many Wolfe descendants carom in every direction, tracing lines into the void like countless neutrinos. (The family tree included in the front of the book comes in handy.) Samuel Thomas conspires with veterans of the Texas Revolution to defect from the American army and join the legendary San Patricio Brigade of the Mexican-American War, only to be captured and branded on his face with a D for “deserter.” A mestiza Wolfe descendant buries five husbands. A bastard Wolfe son hunts down his legitimate half brothers in their border redoubt, seeking to kill them both. (Warning: don’t get too attached to any of the book’s wonderfully drawn characters, for they’ll soon be taken from you by bullet, knife, or yellow fever. One walk-on player is eviscerated and fed to pigs while he’s still alive.)

If it sounds like this book compulsively overfloweth, blame the author’s background, which gives him access to, and a useful sense of distance from, a variety of folklore and legends. Born in Tampico and raised in Mexico, Brownsville, and Florida, Blake referred to himself in his 1998 essay, “The Outsider,” as “a stranger in every tribe.” He’s not a Latino writer in the conventional sense, but few American authors cross borders as easily as he does. In the ten novels he has published since 1995, he has written about American and Mexican gangsters, outlaws, and outcasts.

Country of the Bad Wolfes is a departure from his previous works in that it closely shadows the details of Blake’s own family résumé. It arrives seven years after his last novel (previously, he had maintained a near book-a-year pace); clearly, he has been sharpening his knives and loading his muskets for some time to unloose this rumination on the inescapability of his ancestral Anglo-Mexican legacy. In “The Outsider,” Blake revealed that he was “the fourth generation of men in my family to be born in Mexico, all of us descendants of an American who himself was sired by an English pirate. . . . The pirate was my great-great-great-grandfather Robert Blake, the black sheep of a landed English family.” Like Roger Blake Wolfe, Robert Blake was publicly executed in Veracruz.

James Carlos Blake’s Anglo-American ancestors married Mexican women, and gradually their story became just another Mexican story, much like the one he tells in this book. “Imagine,” one character observes, “coming from people of two different races that had not a blamed thing in common except a love of blood in every which way.” Though nearly everything in Country of the Bad Wolfes is traced back to Roger Blake Wolfe’s diabolical influence, it is noted that he is something of a cipher. “No likeness of him—a sketch, a painting, a daguerreotype—survived,” Blake writes, “and the accepted description of him as handsome was based solely on the family’s penchant for romantic fancy and the genetic testament of their own good looks.”

Do we judge our ancestors by who we seem to be? The Wolfe descendants appear to be marked for misfortune by their pirate ancestry, and the Mexican setting of their lives only heightens the centripetal pull of the murderous disorder that is their birthright. But if the reader is put in mind of classic debates about whether our destiny is shaped by nature or nurture, Blake largely avoids ponderous philosophizing. He’s a natural yarn spinner, not an existentialist.

As in his earlier work, Blake excels in gorily choreographed fight scenes, with all make and caliber of guns discharging, sabers slashing, and body parts taking wing, bringing a literary gloss to the now-familiar CGI-enhanced cinematic point of view, á la The Matrix, which allows us to follow a bullet from the barrel to its target, followed by flamboyant serial ricochets. While Blake keeps you immersed in his wildly picaresque tale, he slowly reels in the novel’s dark metaphysical take-home: it doesn’t matter if your distant ancestry is pre-Columbian or Hibernian, Aztec or Iberian. Sooner or later, it’ll catch up with you. Even upon their burial, Roger Blake Wolfe’s twin grandsons are afforded no graceful farewell, as the narrator foresees the hurricane that will disinter their bones and wash them down the Rio Grande and out to sea.

Is there any solace in such a telling? Perhaps only that someone descended from this bloody saga lived to tell the tale and tell it well.

Very American.

San Antonio writer John Phillip Santos is the author of The Farthest Home Is in an Empire of Fire.

What else we’re reading this month

Smart Thinking, Art Markman (Perigee, $25). UT professor describes three ways to make your brain work better.

The Silence of Our Friends, Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell (First Second, $17). Graphic novel about Houston’s civil rights movement.

The Devil’s Odds, Milton T. Burton (Minotaur, $26). Thriller set on the Texas Gulf Coast during the forties, by the author of Nights of the Red Moon.