This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A couple of months ago the New York Times carried a front-page report of a resolution by the Saint Petersburg, Florida, city council, ordering the last 25,000 people who had moved into that resort community to pack their belongings and move away. Just one week earlier the city council of Austin approved, over citizen protests, traffic plans that would sound the death knell for the city’s oldest residential area by ramming a pair of three-lane arterial streets through its core in the name of alleviating anticipated freeway congestion. A fine-spun bond unites the two events.

The city fathers in Saint Pete did not seriously expect their ordinance to be enforced, of course; they admitted it wasn’t even constitutional. But they passed it as a symbolic act—as a tolling bell to warn against the perils of uncontrolled growth. The action in Austin was equally, if unintentionally, just as symbolic—as a reminder that the philosophy of “bigger is better” is far from dead in Texas, even if bigness must be achieved by sacrificing history and charm.

The “Ninth and Tenth Street Improvements Project” will connect busy Lamar Boulevard with Congress Avenue by widening two placid east-west streets and, at one point, appropriating presently unused street right-of-way to traverse a quiet seven-acre park. In the process it will accelerate commercial development in the area. When that happens, Austin will become a metropolis like so many others, unencumbered by the untidy small-townish blend of homes and offices mixed together downtown. Austin will be Big Time.

The Old Austin Neighborhood, through which the new Ninth and Tenth streets will be widened to carry 21,000 vehicles per day, is the last surviving residential remnant of the original city. Edwin Waller’s 1839 survey staked out the town in the shape of a slightly overweight square and crisscrossed it with an unimaginative grid of east-west streets named after trees (later changed to ordinal numbers) and north-south streets named after famous Texas rivers, with a “West” and “East” Avenue on either side for good measure. In the center, from a site reserved for an imposing Capitol, broad Congress Avenue sloped downward to the flood-prone Colorado.

Austin has long since outgrown this original city, but its perimeters can still be traced from First Street on the south near the riverbank, up hilly West Avenue to Nineteenth, across to East Avenue (now better known as the Interregional Highway, currently Austin’s only freeway), and back down to First. The central swath on either side of Congress contains such downtown enterprise as a city based on its university and its state offices needed in a simpler era; the region south of Sixth has faded into a tawdry, dead-end warehouse district, alleviated by the glitter of automobile dealerships along Sixth and Fifth. The pink granite State Capitol Complex stretches northward from the head of Congress to Nineteenth, liberally interlaced with parking lots; and the area east of the central business district all the way to Interregional is predominantly vacant—the legacy of a recent Urban Renewal project that obliterated, among other things, more than 50 nineteenth-century homes. Except for some restoration along East Sixth the Old Austin Neighborhood—west of Guadalupe Street from Sixth to Nineteenth, four blocks wide—is all that remains.

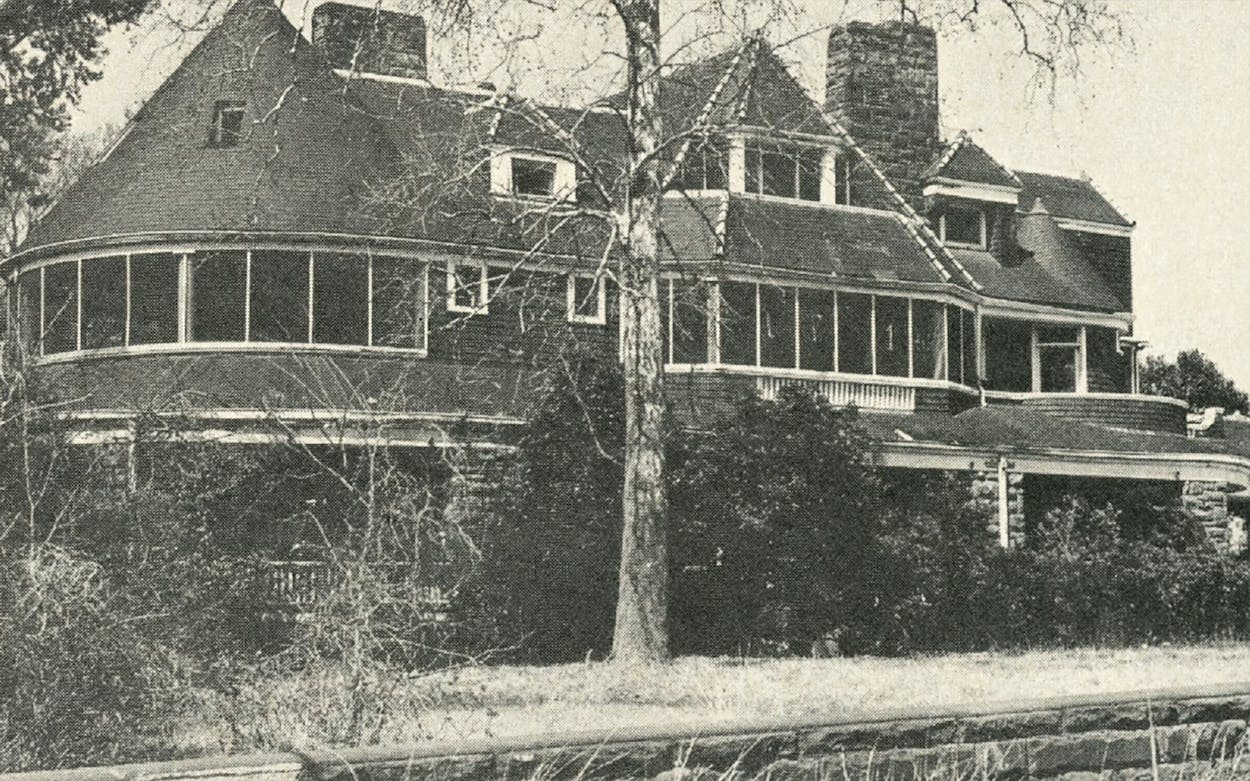

It is Austin’s equivalent, perhaps, of San Antonio’s King William Quarter, though without the self-conscious burnished elegance of that broad-lawned Victorian neighborhood. Except for one small collection of brick and limestone mansions called the Bremond Block, nobody has really set out to preserve the Old Austin Neighborhood, and in that it differs not only from King William but from the picturesque old downtown residential areas in the handful of cities (Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans) that have made a concerted effort to keep their past alive. It simply exists—a haphazard collection of homes and offices, some fine, some shabby, each the product of the affection or indifference of its individual owner.

In the fifteen minutes required to walk from its westernmost edge to Congress Avenue, one can see a wealth of architectural styles ranging from the Texas Republican period (715–717 West Avenue) to late Victorian (708 West Tenth). There is a mixture of stately homes, apartments, and simple cottages. Classical facades (808 West Avenue) commingle with romanesque and mock baronial (500 West Thirteenth). Within the neighborhood the local Heritage Society lists no fewer than 83 architecturally significant homes constructed between 1850 and 1910. One also finds the city’s oldest grammar school, the city library, the Travis County Courthouse, tradition-rich Austin High, antique stores, an occasional restaurant, The Texas Observer, the American Legion, numerous small professional offices, a quantity of pedestrians unmatched by any other residential area of the city, and a steeply sloping grassy park where a string quartet gives concerts on summer Sundays.

Under a canopy of oaks and pecans one can walk for blocks and still be sheltered from the full glare of the midday sun except at street crossings. A stroll discloses the care so many people still lavish on their gardens: the row of pepper plants; the caladiums; the boxes of azaleas ensconced in Alabama dirt; the gay field of zinnias. But one also notices the vacant lots, the empty places where an old home stood not long ago; and watches the construction crew arrive to succeed the wrecker’s ball. Modern office buildings, multistoried and devoid of character, are moving in. More than twenty classic homes have been destroyed in the Old Austin neighborhood since 1960. Others will succumb quickly when the new streets are finished.

Despite the heavy toll, the old neighborhood’s admirers were optimistic until the street plan was approved. Young professionals, particularly lawyers, had refurbished many of the houses and cottages into offices without doing violence to the original architecture. Unobtrusively, they shared the same block with families who had occupied their own residences for 50 years or more. Together they looked askance at the central business district’s concrete-and-steel nudging slowly toward them over the escarpment of San Antonio Street.

They were optimistic because it seemed that Austin’s eccentric growth patterns would spare the central city from the most crushing effects of a noteworthy economic boom. Austin is the fastest growing major city in Texas. The Chamber of Commerce cheerfully forecasts that the population, now 300,000, will reach half a million by 1990 and a million by 2020. Business activity has more than doubled since 1967, the highest rate of increase of any Texas city. In the total dollar value of building permits, Austin ranked fourteenth in the nation last year; by the end of June, 1974, it had risen to eighth. And that is eighth among all cities in the country, not eighth among cities of its size. (Chicago trails in ninth place.)

But the many new businesses have, for the most part, located on the far northern and northeastern edges of the city. Texas Instruments, IBM, Westinghouse, and others have chosen sites north of town. A giant Motorola plant is coming in the northeast. A few large employers have gone south, like the regional offices of the Internal Revenue Service. The ensuing growth has given the city a sausage-shaped elongation, stretching fifteen miles from north to south, but only a third that wide from the east (where minority neighborhoods parry expansion) to the west (where the Colorado swings around like a broad moat).

Because of its peculiar shape, optimists hoped that Austin’s massive anticipated growth would continue to pile up along North Interregional and U.S. Highway 183 in suburban layers, in a succession of mini-cities with their own residential areas and shopping centers. This explosive growth was not ideal, they felt; but if it had to come, far better that it come on the periphery where newcomers could live and shop in communities adjoining the places they worked, rather than press inward to crush the central city. So long as this radically modern suburban-style development spun outward to the remote edges, it left hope that the traditional Austin—the Capitol, the University, the old city, and other older neighborhoods—would be sheltered.

So the optimists hoped, until the Ninth and Tenth Street Improvements Project shattered the illusion. The intense pressure from business interests and the city administration to get that plan moving showed that the powers-that-be confidently expected their Austin to sprout a sparkling, high-rise downtown just like any self-respecting Major Texas City ought to have.

To the downtown business interests, the old neighborhood (still 51 per cent residential) impeded the manifest destiny of a bigger central business district—a district, be it noted, that seems certain to consist primarily of office buildings and bank towers, since most of the typical “Main Street” retail stores have edged their bets onto suburban malls. To them the old neighborhood was an archaic nuisance, even an embarrassment: imagine people trying to live in old homes in downtown Houston or Dallas, for example. That’s just not the way it’s done. Many Texas businessmen still have rather rigid ideas of what a button-popping boom town ought to look like, and their image certainly does not include a residential neighborhood right smack where downtown ought to be.

Besides, if Austin is going to have a spiffy CBD like Houston and Dallas, people need to get in and out of it in a hurry. At present six major thoroughfares link downtown with Lamar: First, Fifth, Sixth, Twelfth, Fifteenth, and Nineteenth. (The last three, it is true, do not penetrate the business district directly, but require the driver to turn his steering wheel 90 degrees, once, to enter the district on any connecting north-south street.) Together, these six thoroughfares provide 27 lanes for traffic between downtown and the west. A layman in the world of traffic engineering could be pardoned for supposing that ought to be enough.

But when Austin’s second north-south freeway, the MoPac Expressway, is completed along its near-western side later in the decade, congestion will increase on the streets (First, Fifth, Sixth, and Fifteenth) that interchange with it. Traffic engineers reasoned that more streets are needed for travelers who want to keep out of the way of these crowds. By making Ninth and Tenth one-way thoroughfares, and by cutting Ninth through the park, there could be two more ways to get between downtown and the west side without bothering the freeway folks. So that is what they proposed, even though the new streets would dead-end into busy Lamar before they reached the freeway.

The proponents of Greater Austin had the enthusiastic support of Mayor Butler, himself a downtown businessman (Roy Butler Lincoln-Mercury, Sixth and Lamar). He viewed with serene poise the distinct possibility that his family’s substantial land holdings near Ninth and Lamar would be enhanced in value by creation of a busy new thoroughfare alongside them.

Residents of the area, including many who officed there, set out to challenge the plan under the banner of the “Old Austin Neighborhood” (OAN). They elected Carolyn Bucknall, tenant of the stately 1882 classical structure at 808 West Avenue, as their chairman, and they began to gather material for what they hoped would be a convincing council presentation: historical records, environmental data, and traffic studies that contradicted the city’s own projections.

The Council hearing on July 18 drew a large and vocal crowd of downtown businessmen, neighborhood residents, environmentalists, and university students. OAN’s presentation included a simple slide show of the many fine homes in the neighborhood coupled with a reading of letters from residents. The Urban Transportation Department countered with a color film, backed by Scott Joplin ragtime, in which the narrator explained how building a road through the park would “open it up for all to use.”

Bucknall had nettled the Mayor considerably by calling for him to abstain because of his family’s real estate holdings along Ninth. On television, the day before the hearing, he promised a “surprise” for her. The “surprise” turned out to be a letter from an attorney for her landlady, Frances Davis Lindsay, expressing the landlady’s support for the Ninth Street extension. It was produced before the Council with an air of gleeful triumph by a property owner who favored the plan, as part of his argument that property owners and not tenants were really the only ones with sufficient “standing” to have their views considered by the Council. It was a position to which the Mayor assented, even though it meant that the opinion of Mrs. Bucknall, an Austin resident outside whose window the proposed street would run, was deemed less consequential than the opinion of Mrs. Lindsay, who lives in Cuernavaca.

In the end Butler did abstain; his vote was not needed. The plan was approved, four to two. Construction contracts are scheduled to be let this fall.

The city insisted it was not doing anything to the neighborhood, just putting some roads through. A visitor to Austin in, say, 1980, can be a better judge of what the future holds in store today, and can decide for himself how much of old Austin will have survived six lanes of traffic, signalized intersections, and the gilded lure of commercial property values. As Ted Siff, a veteran of many community-organizing efforts, who energetically supported OAN, remarked: “Over two dozen major homes of historic value existed along Fifth and Sixth before they made them what they are today. [An overwhelmingly commercial pair of streets, now one-way]. It’s not, you know, just the jackhammers and concrete that’s poured down; it’s basic economics. You can go from Congress to West Avenue making a plot survey of the land values from recent sales, and you can see it. Land values go from about ten dollars [a square foot] in one block, down to eight and nine in the next, and then seven, and by West Avenue they’re about four to five. When they go up to eight or nine—and it’s moving that way—you’re just not going to be able to keep residences in this area. Unless you protect them, they just won’t be financially practical.”

In a world that has an all-too-generous supply of scandals and catastrophes, the ultimate fate of old Austin will never rate very high. It is not the most beautiful old neighborhood in the country—never was—and its apparent sad end is not the result of some immense civic conspiracy. A few people will make some money out of what happens, to be sure, and not many of them will be the people who live there; they seldom are. But the main thing that has happened is that Austin, a small town still wishing to grow up to be a big town, is losing what little is left of its heritage in pursuit of a dream that is so rapidly becoming obsolete elsewhere. Some of these houses were occupied when the sound of Indians could still be heard at night in the high hills west of the river, where the cable television tower now stands. That was a hundred years ago, and some of us hope to live to be a hundred ourselves. It doesn’t require much more than a teaspoonful of respect for the past to drive six blocks out of your way every morning in order to keep alive something like that.

Shallow historical roots are easier to kick aside. Thomas Jefferson was in his grave before Austin was ever planned; we do not have 60 or more generations of ancestors who lived on this land. The only ones we’ve got are the ones who built this very neighborhood, nail by patient nail, and from them we have inherited only what they, in their sometimes awkward way, have left us. It may not be much, but it is all we have.

Senior Editor Griffin Smith has lived and worked in the Old Austin Neighborhood since 1971.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Austin