When did filmmakers decide that sports movies are an effective means of teaching racial tolerance and unity? And when did Texans become so complicit in the propagation of this increasingly insufferable trend?

These are two of the questions that drifted through my mind as I was watching The Express (2008), a drama about Syracuse University halfback Ernie Davis (Rob Brown), the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy. The movie opens with a glimpse of the 1960 Cotton Bowl, with hulking rednecks on the University of Texas defensive line spewing racially charged invective. Later, after a series of golden-hued flashbacks, we return to the climactic showdown, which portrays Longhorns fans in a kind of orgiastic frenzy of hatred (by comparison, the Ku Klux Klan sequences in The Birth of a Nation are positively restrained). Granted, this is an unfortunate chapter in Texas history that should not be glossed over. But the movie’s rendering of the entire era—the snarling businessmen who refuse to allow Davis into a Dallas hotel, the fans mouthing the n-word in excruciating slow motion—turns so cartoonishly over-the-top that it finally proves meaningless.

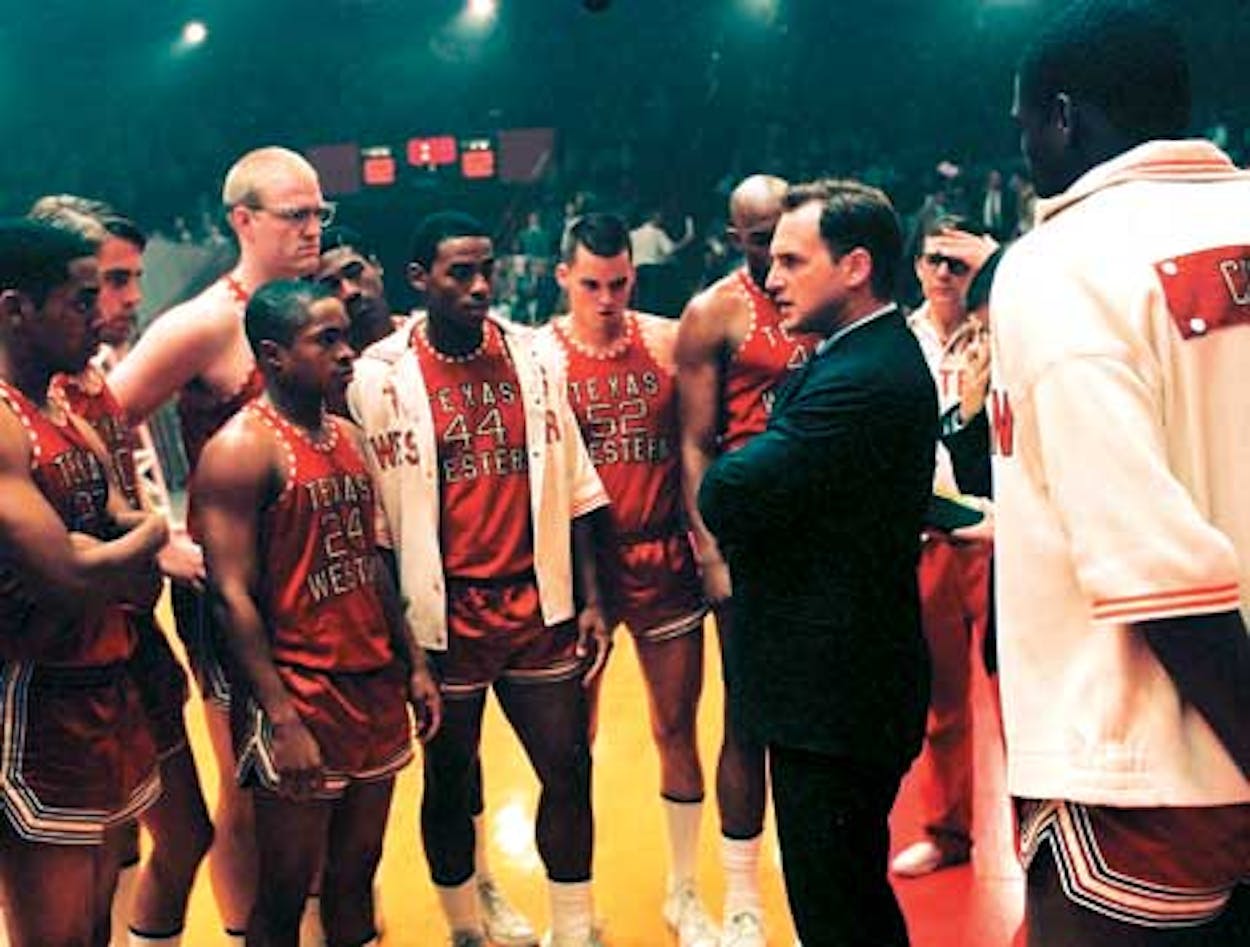

If only The Express were an isolated case of Hollywood trying too hard to put a lump in our throats—and if only Dennis Quaid, who plays Davis’s dogged coach, Ben Schwatzwalder, weren’t the only Texan inexplicably drawn to appearing in these movies. But ever since the success of Remember the Titans (2000), a paint-by-number, Disney-fied drama about a black football coach (Denzel Washington) leading an integrated high school football team in Virginia in the early seventies, American sports films have turned into joyless civics lessons. This epidemic seems particularly pronounced for those pictures set in Texas. Glory Road (2006) earnestly depicts a basketball team with an all-black starting lineup as it faces down racists at its own school, Texas Western College (now the University of Texas at El Paso), and the even bigger racists at the University of Kentucky (the movie is so grindingly predictable that you quickly start rooting for the Wildcats). The Great Debaters (2007), that rare sports movie for nerds, recounts the triumphs of a debate team at historically black Wiley College, in Marshall, that squares off against the white preppies at Harvard in the thirties; it’s a handsomely mounted effort, featuring a superb supporting performance by Longview native Forest Whitaker as the overly conservative college president, that nonetheless suffocates the audience with its nobility. (The sterling exception to this recent rule is 2004’s Friday Night Lights, an eviscerating portrait of a small-town white elite that regards its black football heroes as second-class citizens. But the film is also so ruthlessly dour that it seems to occupy a genre entirely its own. It’s a sports movie for ascetics.)

So why this sudden explosion of high-mindedness? Perhaps it’s because, in an anxious and uncertain era, filmmakers and audiences gravitate to clear-cut and indisputable stories of moral victory. Whatever the reason, though, something crucial has gone missing. Think of the prickly comedy of North Dallas Forty (1979), still arguably the greatest Texas-based sports picture ever made, or the brazen energy of Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday (1999), starring Quaid and fellow Texan Jamie Foxx—a kaleidoscopic portrait of race, sex, hip-hop music, and conspicuous consumption all furiously colliding on and off the football field. Indeed, what so many current filmmakers seem to have forgotten is that, no matter how “important” the lesson being proffered and no matter how “inspirational” the story being told, a sports movie that doesn’t at least provide some measure of playfulness isn’t much of a sports movie at all. (And no, 2006’s unintentionally funny We Are Marshall, starring a wildly unconvincing Matthew McConaughey as the coach trying to resurrect Marshall University’s football program after a tragic accident, does not count as playful.)

It would be one thing, of course, if the messages of these movies felt essential, or at least urgent. Quite the opposite, movies like The Express come across as quaint, even reactionary; the simplicity on display is insulting. Glory Road presents a group of black basketball players so saintly they might as well be spiritual cousins to the “noble Negro” characters Sidney Poitier played four decades ago in the likes of To Sir, With Love (1967) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). Given the pedantic, work-hard-and-act-honorably lessons of The Great Debaters, you’d think several generations’ worth of thorny visions of American race relations, from Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) to Marc Forster’s Monster’s Ball (2001), had never been created. Trapped in the past, The Express, Glory Road, and their ilk are content to congratulate moviegoers (look how far we’ve come!) instead of unsettle them (look at how much work is still left to be done!). And by replaying the same narrative again and again, measuring the achievements of black athletes against historical yardsticks established by white athletes, they’re beginning to do more harm than good. They reduce blacks to symbolic representatives of their race, as opposed to complicated, sometimes heroic, sometimes flawed individuals.

A modest plea to sports-minded moviemakers: Put aside your concerns about intolerance on America’s playing fields, at least until we’ve all had time to take stock of the racial ethos of the impending Obama era. In the meantime, how about restoring some of the rakish charm of Tin Cup (1996), the ribald spiritedness of Bull Durham (1988), or the rowdy, propulsive energy of Varsity Blues (1999)? (I would say, “How about a remake of a lovable loser classic like The Bad News Bears?” but alas, Richard Linklater already botched that one rather horribly.) Heck, if there’s an ambitious filmmaker out there in search of viable material, he need only look at the current Dallas Cowboys season, a rollicking tragicomedy that’s one part Rudy, two parts Grumpy Old Men. (Since Texas actors are invariably attracted to such projects, might I suggest Barry Corbin as Wade Phillips?) Because unless filmmakers stop gunning for the Nobel Peace Prize and start remembering that the best movies are less black and white than endless variations on the shade of gray, the sports genre might just be in danger of running out the clock and expiring altogether.

The Imperfect Storm: An unpromising forecast for a new basketball flick.

If you still haven’t had your fill of fact-based, sports-centered tales of triumph over dire circumstance, here comes another one: Hurricane Season, which follows a suburban New Orleans high school basketball coach who assembles a team of players displaced by Hurricane Katrina. (It’s not to be confused with another Hurricane Season, based on Neal Thompson’s book, about a New Orleans high school football team struggling to reassemble in the aftermath of Katrina, currently in development at HBO. Who says Hollywood has no original ideas?) Already there are reasons to be dubious: For one thing, it was originally scheduled to open on Christmas Day, before it got bumped to the less competitive month of March, which is rarely a good sign; for another, it’s directed by the same guy (Tim Story) who made Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer. But the cast at least holds promise: Forest Whitaker (yes, him again) plays the coach, while hip-hop star Bow Wow, fresh off a surprisingly accomplished supporting turn last season on the HBO series Entourage, plays one of the team members.

Christopher Kelly is the film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.