I was working overnight at a Seattle hospital when Hurricane Harvey made landfall near Port Aransas. Between patients, I pulled up news reports on the storm. “A hurricane is hitting my town,” I told another resident. “Right now. It’s hitting my town right now.”

At first there was nothing from Port Aransas: the island had been evacuated early, and no TV reporters had arrived. Then, over the next few days, my social media accounts lit up with pictures. I clicked through hundreds of them hoping to see our house—the house my father built—but there was nothing from that end of Cotter Street. When my mom finally texted a picture of the house, I cried with relief. From the outside, everything looked fine.

Two weeks later, I flew home. I had a layover in Houston, and the small jet to Corpus Christi was full of my people: sunbaked men in T-shirts with fish on them, grandmothers in careful makeup, tough women with faces lined from smoking. When the pilot announced the arrival gate in Corpus, we all laughed. The airport is so small that it doesn’t matter what gate you come to. The plane swoops in low over the glittering refineries along the Corpus Christi channel to land, and you’re there.

My parents had stocked the car with hot Tex-Mex from a joint in Flour Bluff. I don’t know if you have ever suffered as I have in a land without Tex-Mex, but I don’t recommend it. The refried beans were glorious, and I felt my battered Texan soul come back into my body. There was also a small cooler with iced Topo Chico. My dad had stuck a beer in there, but Mom briskly reminded us of how many state troopers were stationed in Port A since the hurricane, so I left it alone.

Corpus looked okay. There was some wind damage, signs blown over and shingles missing, but nothing shocking. The closer we got to home, the worse it got. There were telephone poles blown over on Highway 361, then the first ruined buildings, then places I had known reduced to piles of debris.

“It looks so much better now compared to last week,” my mother said. “They’ve done a lot.”

Just outside town, we passed the mountain: a heap of broken wood and twisted metal higher than any building on the island, guarded by slumbering bulldozers. They looked tiny beside it.

My mom reached back to hold my hand.

“Well,” Dad said, gesturing toward the mountain. “There’s Port Aransas.”

The next day, I drove around the island with my mother. It seemed like Harvey had gone house to house, wreaking havoc for some while leaving others barely touched.

It was like that for my mother’s friends. Lynn’s garage flooded. June’s place was mostly fine. Sally Jo lost everything. Tomi’s house was blown right off the pier-and-beam foundation. It floated to the back of her lot and was inundated; she lost nearly every possession, but a row of crystal champagne glasses on top of one bookshelf stayed perfectly intact.

Asking after one another became part of hurricane etiquette, and everywhere we went it was like that. People asked, “How’d you come through?” or “How’d your place do?”

“We were lucky,” my mom said in the grocery store, holding a can of tomato paste and some toilet paper. “The ceilings came down, but the roof stayed on.” She said it again in the post office and at the civic center: We were lucky.

I rode shotgun around the island in a kind of daze. The streets were lined with piles of rotten drywall and insulation from gutted houses, and state troopers were everywhere. One stopped to help my dad haul debris across the yard. “That’s kind of you,” Dad said, “but you should just keep on keeping the peace.”

There were also volunteers everywhere: cooking spaghetti in the parking lot of the grocery store, nailing tarps to damaged roofs, handing out five-gallon buckets full of sponges and Lysol with a card from some small-town church. Texas remembered us.

Nancy Hyder had lost her husband earlier in the year, and she was standing in her driveway watching two volunteers from Victoria haul a downed tree out of her backyard when she just burst into tears. “I never could have done it,” she told me later, sitting under the duct tape and tarps that now form her kitchen ceiling. “I know they got damage too. But they came all the way here to help.”

Natural disaster turned out to be a social event. When the water started working on Cotter Street, friends hauled their laundry over to use our washing machine. Side-Job Bob came by to work on our damaged deck, and then he and my mom sat in the shade while Dad—exhausted from working—napped. Mom threw Bob’s laundry in the machine, then offered him a glass of wine.

Bob dithered a bit, until Mom finally said, “Well, Bob, how about a beer?”

At that, he brightened up, and the two sat talking until Dad emerged from the nap in his underwear. My folks were equally shocked: Mom to see Dad coming out in his underwear in front of company, and Dad to see Mom getting tipsy with Side-Job Bob.

There was a kind of glory in the aftermath: the town coming together, the newspaper cranking out stories, the plans to rebuild. Sons and daughters of Port Aransas rallied. They formed a charity to raise funds for trailer homes for island families. By the time school opened back up on October 16, Homes for Displaced Marlins had already secured new housing for two families with young kids.

I don’t mean to suggest it’s all rosy. People lost their houses and their jobs, and the rejections from FEMA have started rolling in. I did my medical training in Galveston after Hurricane Ike, in 2008, and I know what comes in the wake of natural disaster: poverty, addiction, mental illness, domestic violence. The social safety net we so desperately need—access to medical care, to affordable housing, to decent jobs—is not forthcoming from the government.

Already my parents and their neighbors are feeling the strain. That first glory has faded, and debris still lines many of the streets. Some families are not coming back. Bitterness will set in, and all along the Texas coast the poorest will suffer the most.

Even so, having been home for just a few days, I remembered the essential grace of the community that made me who I am. The people of Port Aransas are trying to survive in a disaster area every day, but they still turn toward one another instead of away. They do not let one another starve; they do not leave one another comfortless.

One morning, I drove with my mother to see if Station Street Pier was still there. I must have spent a hundred evenings there with my brother, fishing for sand trout and specks under the lights of the pier. The flounder would run through on the first cold front, and we’d pull up enough for a feast.

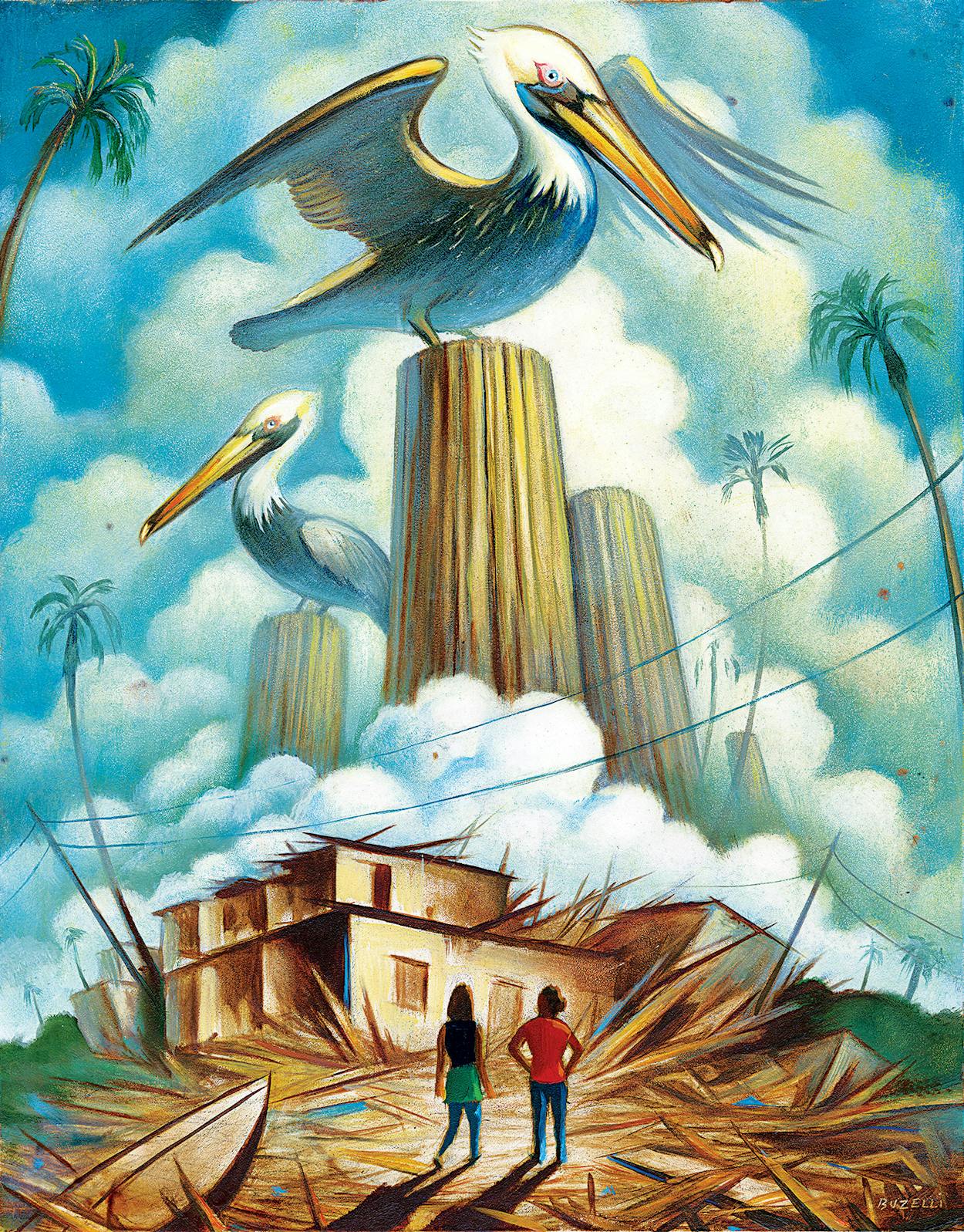

I walked out to where the bulkhead hit the pier, but it’s just empty pilings now. That place, like so many others that made up our childhoods, is gone. The tide was coming in, and the water of the ship channel ran quietly around the pilings where the pier had been. Out across the channel I could see St. Jo’s Island. On the wrecked pier’s farthest pilings, a pair of brown pelicans was roosting.

I walked back to the car. I closed the door behind me and looked again at those pelicans. “Well,” I said to my mom, “they’re still here.”

“That’s right,” she said. “We’re still here.”

I don’t think she heard me, exactly. But it didn’t matter; we were both speaking the truth.

Rachel Pearson is a resident physician in Washington State and the author of No Apparent Distress: A Doctor’s Coming-of-Age on the Front Lines of American Medicine.