This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The widest gulf on Capitol Hill divides not Republicans and Democrats, nor liberals and conservatives, but electoral politicians and legislative politicians. There is a time-honored dictum in Washington that the more one is revered by the press and public, the less one is respected within Congress itself. No better example could be found than the bitterness Lyndon Johnson felt toward John F. Kennedy when both sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960: Kennedy was never on the Senate floor, he never did his homework, he never passed any bills, he had never done anything except run around the country trying to get himself elected president. Johnson couldn’t understand why he was losing to someone with so little fondness for what he considered the real political arena.

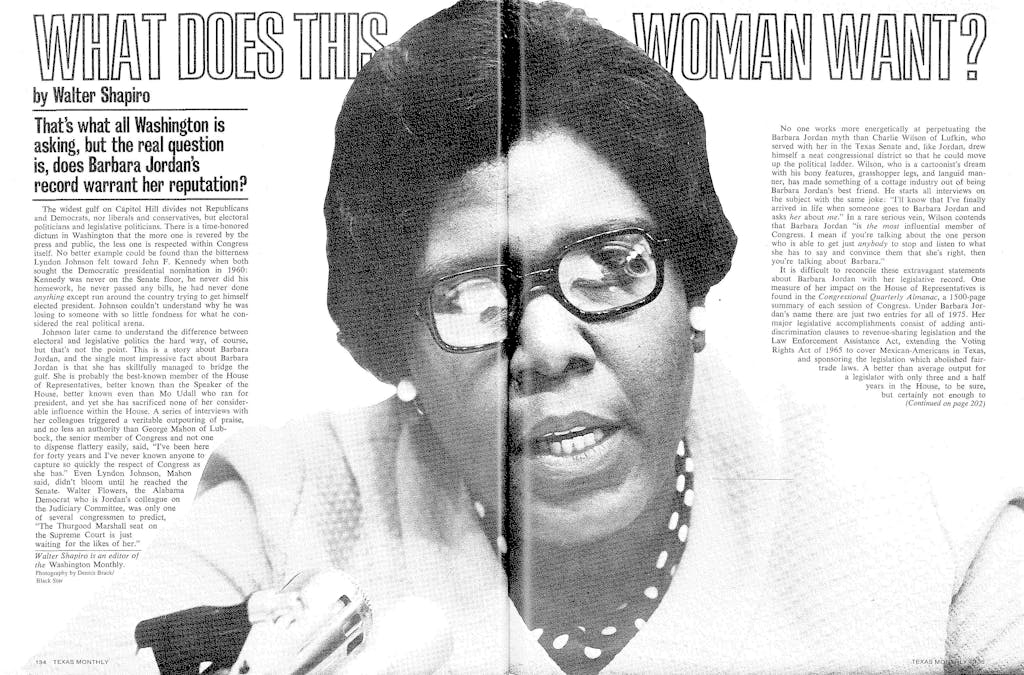

Johnson later came to understand the difference between electoral and legislative politics the hard way, of course, but that’s not the point. This is a story about Barbara Jordan, and the single most impressive fact about Barbara Jordan is that she has skillfully managed to bridge the gulf. She is probably the best-known member of the House of Representatives, better known than the Speaker of the House, better known even than Mo Udall who ran for president, and yet she has sacrificed none of her considerable influence within the House. A series of interviews with her colleagues triggered a veritable outpouring of praise, and no less an authority than George Mahon of Lubbock, the senior member of Congress and not one to dispense flattery easily, said, “I’ve been here for forty years and I’ve never known anyone to capture so quickly the respect of Congress as she has.” Even Lyndon Johnson, Mahon said, didn’t bloom until he reached the Senate. Walter Flowers, the Alabama Democrat who is Jordan’s colleague on the Judiciary Committee, was only one of several congressmen to predict, “The Thurgood Marshall seat on the Supreme Court is just waiting for the likes of her.”

No one works more energetically at perpetuating the Barbara Jordan myth than Charlie Wilson of Lufkin, who served with her in the Texas Senate and, like Jordan, drew himself a neat congressional district so that he could move up the political ladder. Wilson, who is a cartoonist’s dream with his bony features, grasshopper legs, and languid manner, has made something of a cottage industry out of being Barbara Jordan’s best friend. He starts all interviews on the subject with the same joke: “I’ll know that I’ve finally arrived in life when someone goes to Barbara Jordan and asks her about me.” In a rare serious vein, Wilson contends that Barbara Jordan “is the most influential member of Congress. I mean if you’re talking about the one person who is able to get just anybody to stop and listen to what she has to say and convince them that she’s right, then you’re talking about Barbara.”

It is difficult to reconcile these extravagant statements about Barbara Jordan with her legislative record. One measure of her impact on the House of Representatives is found in the Congressional Quarterly Almanac, a 1500-page summary of each session of Congress. Under Barbara Jordan’s name there are just two entries for all of 1975. Her major legislative accomplishments consist of adding antidiscrimination clauses to revenue-sharing legislation and the Law Enforcement Assistance Act, extending the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to cover Mexican-Americans in Texas, and sponsoring the legislation which abolished fair-trade laws. A better than average output for a legislator with only three and a half years in the House, to be sure, but certainly not enough to qualify her for a mantle of greatness.

Why then is Barbara Jordan so revered within the House of Representatives?

The answer lies in her style—not her speaking style, though that is part of it, but her legislative style, which is unique among the 435 members of the House. It has many aspects, but the one consistent thread is this: she goes to great lengths not to identify herself with any group, bloc, or constituency. She is unqualifiedly a liberal Democrat (on partisan issues where the majority of Democrats vote one way and the majority of Republicans vote the other, she votes with the Democrats 91 per cent of the time), yet she takes pains to preserve personal ties to the rest of the Texas delegation and Southern conservatives, even the mossbacks. Her primary legislative interests have been minority issues, but on the House floor she separates herself from the black caucus and the other women in the House. By taking care to adhere to the old ways, by emphasizing symbolic gestures, and by showing a reverence for Congress as an institution, she has managed to create the illusion that her vote cannot be taken for granted, when in fact it is almost as predictable as, say, her black woman colleague Shirley Chisholm’s on all issues except energy.

Of course, Jordan came to the House in 1973 with certain advantages. Her reputation as the first black woman elected to Congress from the South preceded her. And while there were dozens of look-alike white male freshmen, no one was likely to confuse Barbara Jordan with anyone else. Still, it was another black woman—Yvonne Braithwaite Burke of Los Angeles—who was singled out as the real star; Burke had been temporary chairman of the 1972 Democratic Convention and her picture, not Jordan’s, dominated the women’s pages. Burke and Jordan were the two fledgling Democrats singled out by the Kennedy Institute at Harvard to attend a special month-long seminar just before they took office (William Cohen of Maine and Alan Steelman of Texas were the Republicans). Not once during that month did the two black women discuss any unique problems they might encounter in an overwhelmingly white male institution.

Her first term hadn’t even begun before Jordan began to establish her independence. Just before the swearing-in ceremony, Tip O’Neill of Massachusetts, exuding Irish conviviality, put one arm around Jordan’s shoulder and another around Yvonne Burke’s and began to steer them toward a group of liberal Democrats on the floor. Jordan broke away, grabbing the arm of the nearest Texan, and there are those who say she’s never forgiven O’Neill (who is Carl Albert’s probable successor as Speaker in 1977) to this day.

There is a widely circulated story in Washington concerning Jordan’s first break with the Congressional Black Caucus. She wanted to be assigned to the Judiciary Committee, so the story goes, but the Black Caucus urged her instead to ask for Armed Services. Just why a freshman legislator with no military bases in her district should volunteer for oblivion on Armed Services the caucus did not explain; all they cared about was that Armed Services was lily white, while black congressman John Conyers was already a senior member of Judiciary. Jordan, like most freshman legislators facing a difficult decision, sought outside advice.

“I called Lyndon Johnson to tell him what I had in mind and he thought that Judiciary was a good idea,” she says with even more than her customary precision. Other sources close to her at the time add that Johnson told her that the antimilitary mood in the country meant that Armed Services was a dead-end assignment. According to the story, Johnson called Wilbur Mills, then chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, whose Democratic majority handled their party’s committee assignments at that time. (Since Mills’ fall, that job has gone to the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee, of which Jordan is a member.) Johnson’s intervention, which came just a few weeks before his death, is said to have made the assignment a foregone conclusion. Reputedly Mills, who then oversaw committee assignments with an iron hand, came to the Judiciary Committee and said, “Now that Barbara is going on, who else do we want?”

The story is an integral part of the Barbara Jordan legend, the Washington source of the notion that she is LBJ’s true political heir. It is odd, therefore, that Wilbur Mills’ description of the phone call from Johnson is completely at odds with the conventional version. Mills says Johnson did indeed call—but he asked if she could go on Armed Services. Since there were already two Texans (Richard White of El Paso and now-retired O. C. Fisher of San Angelo) on Armed Services, Mills says he suggested Judiciary instead. Perhaps the most significant aspect of the entire episode is that Mills says this was the only time Johnson ever called him concerning committee assignments.

No one, of course, had any inkling in January 1973 just how pivotal her appointment to Judiciary would turn out to be. If there is any one moment that Barbara Jordan became Barbara Jordan, it was when the television cameras focused on her a year and a half later and she began her indictment of Richard Nixon:

“When the Constitution of the United States was completed . . . I was not included in that ‘We The People.’ I felt for many years that somehow George Washington and Alexander Hamilton had left me out by mistake.” And then: “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of that Constitution.”

Judiciary chairman Peter Rodino, carefully working his way through the impeachment proceedings, came to rely increasingly on two Texas congressmen for political advice: Jack Brooks, because he was highly partisan, and Barbara Jordan, because she wasn’t. Her influence was accentuated because she refused to be counted as an automatic vote against Nixon just because she was black. The other two black members of the committee, Conyers and freshman Democrat Charlie Rangel of New York, were among the most certain votes for impeachment. (“I too was determined to act ‘responsible,’ ” Rangel said recently with a laugh, comparing his stance to Jordan’s, “but I knew that son of a bitch was guilty.”) This refusal to be ideological is the most characteristic and fundamental element of Barbara Jordan’s appeal to her colleagues.

Nowhere does Jordan announce her independence more forcefully than in her choice of seats on the House floor. Congressmen have no assigned seats; they spend most of their time off the floor or, when they are present, milling around outside the railing that encircles the seats. When they do sit, Democrats tend to fan out from the middle aisle according to ideology, with the more liberal members sitting far to the left as they face the Speaker’s podium. Jordan, however, can almost always be found on the center aisle, the Democrats’ right flank, about three rows from the rear of the chamber. As Walter Flowers puts it, “She almost has a pew in the center aisle where the Southern conservatives sit.” Bob Eckhardt, her fellow Democrat from Houston and the head of the liberal Democratic Study Group, was even more blunt: “By sitting near the aisle, she almost consciously doesn’t admit to being a liberal.”

The seat works to her advantage in other ways. Because she is close to the main door to the chamber, congressional patriarchs often seek her out as they come pouring in for a vote from their offices or the House gym. They know they can count on her not only to provide a cogent explanation of the bill or amendment, but—unlike most liberals—also to refrain from proselytizing them.

“Since she sits near the aisle, I’ll come in and ask her what the pros and cons are,” says George Mahon. “She’ll say something like, ‘George, coming from your district and with your conservative views, I think you want to vote no.’ ”

Much of her day is spent just sitting on the floor of the House, listening and waiting for people to come to her. (She rarely leaves her seat to talk to someone else.) Originally this may have been a mechanism for quick digestion of the rules of the House, but now it is more a convenient way for her to hold court. There may also be physical reasons for her staying close to the floor during a legislative day. She simply isn’t nimble enough to be sure of getting from her office to the chamber in the fifteen minutes allotted for a roll call vote. Her administrative assistant confirms that she has “a damaged cartilage behind the knee which causes her to limp when she doesn’t have the time to get therapy.” Her sheer bulk also limits her mobility, although she has lost at least 50 pounds since the beginning of the year on a strict diet.

Her constant presence reassures the mossbacks; it exhibits a reverence for Congress as an institution as well as a dedication to hard work. She sets them at ease in other ways as well. Although the Americans for Constitutional Action recently gave her a score of only 5 out of 100, making her one of the least conservative members of the House, she doesn’t make a career out of being a liberal. She has consistently turned down requests to make campaign speeches for her Democratic colleagues, and when the technically nonpartisan National Committee for an Effective Congress (which seldom contributes to anyone except liberal Democrats) asked her to sign a national fund-raising appeal, she not only declined but also added that she wouldn’t even have given them an appointment had she known what they wanted.

“She’s an old-fashioned cloakroom muscler,” says a congressional staffer, “and it makes all those old-fashioned cloakroom musclers feel good.” When crusty Beaumont Congressman Jack Brooks, variously described as the meanest and/or the crudest man in Congress, starts telling locker room stories at Judiciary sessions, Barbara Jordan laughs appreciatively along with the men. The entire effect on conservatives, says the staffer, is that “they’re so delighted that someone who is black and a woman isn’t a new politics type.”

“She’s very warm in give and take,” says Walter Flowers, “but she will never tell you what Barbara Jordan thinks or what her outside interests are. I don’t know where she lives or what she does on weekends.” Ed Mezvinsky of Iowa, another Judiciary colleague, puts it this way: “She has that reserve. It’s her shoulder that is being used, rather than Barbara ever using someone else’s shoulder.” One of the more unlikely members to use her shoulder was Wayne Hays. After his first speech to the House defending his relationship with Elizabeth Ray, Hays immediately came over and sat down next to Jordan.

The reserve is a crucial element in Barbara Jordan’s style. It sets her apart from the moderates and conservatives, even while so much else about her makes her seem like one of them. It is also the quality that has enabled her to retain her influence in the House despite her widespread public adulation outside. Her House colleagues know that she makes no effort to court the press. Instead, they come after her. Other congressmen hire staffs to get them publicity; Barbara Jordan expects Bud Myers, her administrative assistant, to serve as a buffer between her and the outside world. Myers, who is the only black ever to hold a high-level position on Jordan’s Washington staff, admits that part of his job is “to fight off the national press.”

In the forties, A. J. Liebling wrote about how Colonel Robert McCormick of the Chicago Tribune began one of his famous travelogues by announcing, “I’ve just come from an interview with General Franco,” and then never bothered to mention what the Spanish dictator said. The anecdote comes to mind because the difficulties of getting an interview with Barbara Jordan are far more interesting than anything she actually says. Take away the commanding voice and the distinctive inflections, study the mere words by themselves, and they have all the intellectual substance of Cream of Wheat. Despite her reputation as an orator, she does not talk in anything resembling perfect syntax. It is the type of experience after which one cannot help but wonder, “What is all the hubbub about?”

The final and perhaps most enlightening element in Barbara Jordan’s style is the way she handles her race and sex. She has repeatedly said, “I’m not a professional black or a professional woman, but a professional legislator.” Her social interaction with the rest of the House underlines these priorities. There is a story in Washington that Jordan was once asked why she never sat with the other blacks on the House floor. She is said to have replied, “I don’t know where they sit,” a reference to the fact that most of them spend little time on the floor. On the day Congress adjourned for the Republican Convention, there was a typical scene in the chamber: Jordan was seated one chair from the center aisle, flanked by Omar Burleson and Charlie Wilson; at the opposite end of the same row, totally ignored by their male colleagues, were Yvonne Burke and Pat Schroeder, an activist congresswoman from Colorado.

Although Jordan’s relations with the Black Caucus have improved somewhat since a frosty beginning, they are still on the chilly side. Most blacks tense visibly when asked about Jordan, and in any event a sense of black solidarity would mute the criticism they so evidently feel about her independent role. The usually outspoken John Conyers totally refused to discuss the subject, even on an off-the-record basis, saying only that it “would be potentially detrimental to me, to the Black Caucus, to Barbara Jordan, and to our relationship.” Caucus past president Charlie Rangel, who could not have been unaware that Jordan once publicly chided the caucus for trying “to be the Urban League, the NAACP, the Urban Coalition, and the Afro-Americans for Black Unity all rolled into one,” denied any knowledge that Jordan had ever uttered the slightest criticism of the group. Current caucus chairman Yvonne Burke, whom Jordan has long since eclipsed, was likewise reluctant to discuss Jordan’s relations with the caucus. Choosing her words carefully, Burke said, “I never thought that Barbara went out of her way to avoid women or blacks. She just hates meetings.” Even Ron Dellums from Berkeley, California, who vies for the dubious honor of being the most radical member of the House, said only, “If you accept the assumptions by which Barbara Jordan enters the House, then there’s an impeccable integrity.”

For her part, Jordan now has only praise for the caucus and its professional staff. In most cases—oil and gas issues being the outstanding exception—she votes the same way the rest of the blacks do, and even on energy questions she jumps back and forth. But her style overshadows her voting record: she is perceived both by the Black Caucus and by her white colleagues as an independent.

Jordan’s relationship with her female colleagues is much less complicated: she avoids them. In early 1975, Pat Schroeder, Yvonne Burke, and Bella Abzug organized a weekly luncheon of congressional women. Barbara Jordan never attended. In mid-1975 a dozen congresswomen went on a junket to China, but Barbara Jordan wasn’t among them.

When she wants to, though, Barbara Jordan can exploit to the hilt her unique role as a black woman. “There is something special about tonight,” she announced to the Democratic Convention. “What is different? What is special? I, Barbara Jordan, am a keynote speaker.” Many of her speeches begin with such references, calling attention to her symbolic importance, including, of course, her impeachment address.

The truth is that despite her attempts to disassociate herself from blacks and women, virtually all her legislative efforts have been on behalf of minorities. Her major triumph was the extension of the Voting Rights Act to Mexican-Americans in Texas (Jordan’s district is 20 per cent Spanish-surnamed). She has done some behind-the-scenes work to deflect anti-abortion amendments in the House and has pushed a bill devised by Michigan Congresswoman Martha Griffiths to extend Social Security coverage to housewives or, as they are called in the bill, “homemakers.” Griffiths retired in 1974, and Jordan has reintroduced the bill, although it is still in committee. Yet Jordan feels uncomfortable labeling this as “women’s legislation.” When pressed, she finally said, “I am guessing that there are more women doing housework than there are men.”

She has focused many of her energies on adding antidiscrimination language to the Law Enforcement Assistance Act and revenue-sharing laws. In fact, however, antidiscrimination is not so much Jordan’s passion as it is her one legal specialty. Her highly visible role during impeachment and her unquestioned skills as a political legislator have tended to obscure the fact that she is not a very experienced lawyer. Her colleague Walter Flowers says kindly, “Barbara is still developing as a lawyer.” A close observer of the Judiciary Committee was more critical: “She’s not a great legal thinker, she doesn’t want to look at problems as a lawyer. She’s not an enormously creative thinker in terms of new ideas or ways to express things.” Yet during Watergate the press naively described her as having the best legal mind on the committee (which is composed of 33 lawyers), and talk abounds in Washington that Jimmy Carter will appoint her Attorney General or Supreme Court justice. The thought clearly pains legal craftsman Bob Eckhardt, who says, “Barbara is not a legislative technician, she’s a framer of broad ideals.”

When one examines her legislative record closely, there is little evidence that Barbara Jordan has a clearly focused political philosophy outside of civil rights. A prime example of the narrowness of her legislative concerns came during her first year in the House when she was appointed to the joint House-Senate conference committee on the Law Enforcement Assistance Act (LEAA). Because Herman Short, Houston chief of police at the time, stubbornly refused to accept federal money, Jordan had little interest in anything other than its antidiscrimination clause. “She had John McClellan [an arch conservative senator from Arkansas] eating out of her hand,” said one observer with awe, “but the pity was that she had almost nothing she wanted to ask for. She could have influenced LEAA policies for the cities so that they would not have had to go through the states to get funding. But she made a parochial judgment on the basis of what impact the bill would have on Houston, which was nil.”

That anecdote seems to sum up Barbara Jordan’s career at this point: she has immense power but so far she has declined to use it. The more one probes her record in the House, the more one builds a picture of a shrewd poker player, who sits at the table behind a vast mound of chips. As the game drags on, she plays more and more cautiously and begins to wonder if there is any hand worth risking more than a few of her hard-earned chips on.

Barbara Jordan doesn’t bleed. She has capitalized on that fact in a Washington where all black women are expected to be bleeding hearts. She has so carefully constructed a cool, rather than hot, manner that it is difficult to imagine her being impassioned about any issue. Her liberal voting record seems genuine enough, but it is hard to envision an issue so transcendent that it would not be a perverse form of slumming for her to fight for it.

After three and a half years in the House, the relevant question has become: what is Barbara Jordan saving all those chips for?

Walter Shapiro is an editor of the Washington Monthly.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Barbara Jordan