This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

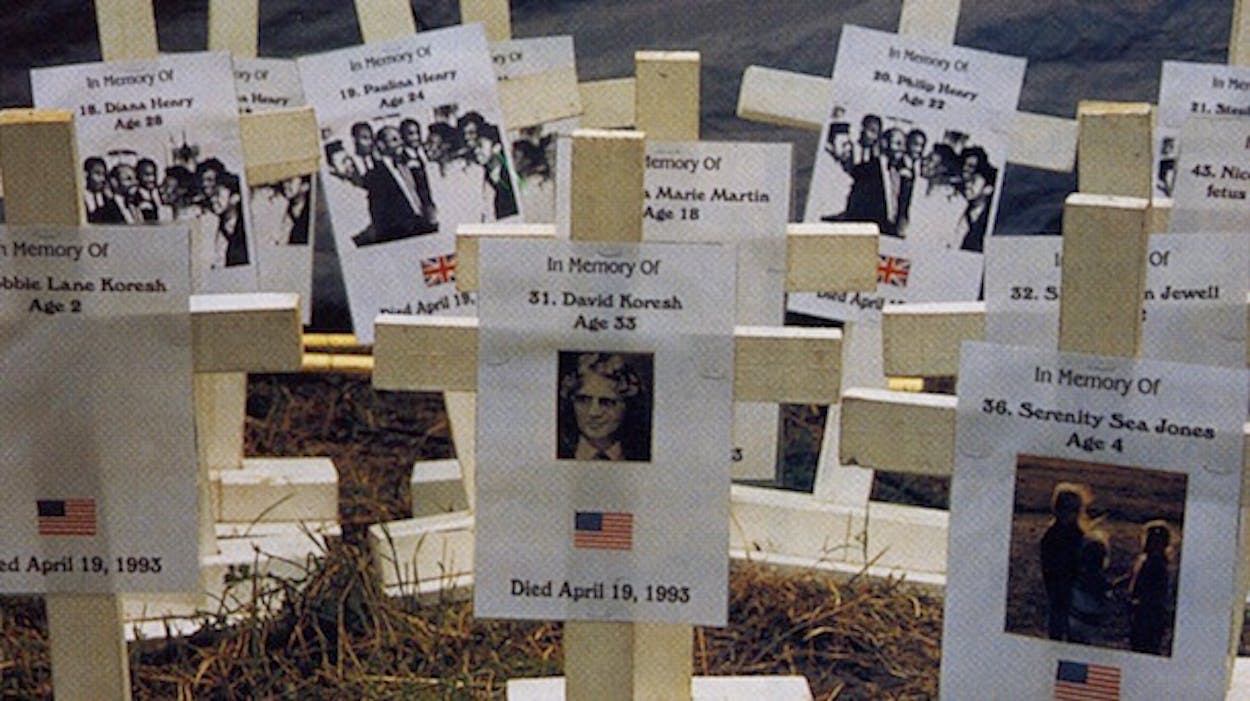

AUTHOR’S NOTE: On April 19, 1993, when Mount Carmel burned to ashes, polls showed that most Americans held David Koresh solely responsible for the deaths there—even President Clinton blamed those who died: “They made the decision to immolate themselves,” he declared.

On April 19, 1993, I was among a dozen people who spoke at a memorial for Mount Carmel’s resident dead, held on the grounds where they had made their lives. As that rainy, gray morning opened, few of us expected that the nation would soon turn its attention back to the events of 1993. But then a bomb exploded in Oklahoma City, and everything changed.

Shortly after the end of the siege at Waco, I had begun to investigate what happened. During the next eighteen months, I pored over more than 30,000 pages of documents, including some that have been kept secret since 1993. I interviewed survivors of Mount Carmel and spent months trying to gain an understanding of their religious beliefs because most of their statements and actions could not be understood without a biblical context. I also tried to speak to veterans of the assaults—ATF raiders and FBI besiegers—only to learn that they are still under gag orders because of pending lawsuits brought by some of the survivors. From extensive Justice and Treasury department reports, congressional hearing records, depositions, trial testimony, and grand jury transcripts—from the materials and people available—I was ultimately able to piece together answers to some of the lingering questions about the Waco affair.

Although an arsenal of illegal weapons was found inside the compound, I now believe that the initial raid upon Mount Carmel—in which five residents and four ATF agents were killed—was part of an offensive whose goal was to impress congressional budgetmakers and the public, as much as to enforce gun laws. It was, in other words, a public relations event. ATF agents even called the gun grab “Showtime.” The agency’s brass misled Governor Ann Richards when they described a “drug nexus” at Mount Carmel to persuade her and the Texas National Guard to supply them with helicopters—good video-footage props—and the first shots fired during the initial raid, on February 28, 1993, were fired either at those helicopters or from them, not during the ground combat that the world witnessed on TV. The defenders of Mount Carmel, eight of whom were sentenced to prison terms in a San Antonio trial last year, may have fired their guns out of self-defense or simple fear, but, I now understand, their theology also instructed them to kill in order to save Koresh.

Once the guns at Mount Carmel went silent, a seven-week siege ensued, during which 21 children and 14 adults came out of Mount Carmel. Many people still wonder why the Waco Messiah and the rest of his followers didn’t surrender rather than risk renewed bloodshed. The answer, I found, is essentially in the story of the ark. Noah’s family entered the ark before the onset of the Great Flood and waited for it to begin. Koresh’s followers believed that they were living in an ark, awaiting the world’s destruction a second time.

But the most persistent and most crucial unanswered questions from the 1993 events are, Why didn’t the FBI wait out Koresh and his flock? and Who started the fatal blaze? The inferno that ended the FBI tank and tear gas assault on the morning of April 19 brought about the deaths—mostly by smoke inhalation, some by suicide—of 73 people, including 23 children. The most widely held explanations for the fire were that the Davidians set it themselves or, as survivors believe, that the tanks knocked over kerosene lamps, which started the blaze. A third and largely overlooked explanation is that the powdery tear gas used—one that was mixed with methylene chloride—could have caused explosions and fires. An evaluation directed by a Houston fire expert who is a longtime associate of the ATF pinned the blame squarely on the residents, but that contention, like many others, is now coming before review in Congress and in the courts, where civil suits filed against the government by survivors and kin are crawling toward trial dates. Because of the numerous dead—of both April 19, 1993, and April 19, 1995—the nation is taking another look at what happened at Waco.

The excerpt that follows is from The Ashes of Waco by Dick J. Reavis, to be published in July by Simon and Schuster. Copyright ©1995 by Dick J. Reavis.

By mid-March, neither negotiations nor unorthodox tactics had produced the resolution that the FBI sought, and its agents were ill at ease in Waco. The some 720 lawmen who were in town—250 from the Bureau, 150 from the ATF, and a scattering from other federal agencies and the Texas Department of Public Safety—had to be housed, along with an average of nearly 1,000 members of the press. The problem went beyond cost: There was a shelter shortage. The town’s first- and second-rate hotels were bulging with guests, and when the federal lawmen went looking for housing, they found that Waco’s apartment occupancy rate had been at 90 percent before the siege began. Because the agencies were shorthanded and living quarters were scarce, the lawmen assigned to the Waco case worked in two- and three-week shifts, piling up overtime—and longing to return to their homes. Early in March the Tourism Division of the Texas Department of Commerce had postponed a series of television ads, reasoning that nobody would want to visit the state anytime soon, and town residents, tired of the bad jokes and quips about “the wackos in Waco,” began affixing to their cars stickers that read “Waco Proud.” As each day passed, pressure built inside and outside the ranks for a speedy end to the standoff.

In late March FBI commanders on the scene began sketching plans for a tear gas assault. The plan worked its way up to Washington, and on April 12 it was presented to Janet Reno, the nation’s new attorney general. The plan called for easing the residents out of Mount Carmel by injecting tear gas into one section after another of the sprawling residence hall—which included a gymnasium, a cafeteria, and a chapel—narrowing its habitability over two days. If this measure failed, the field commanders had a backup. In its report on the affair, the Justice Department, perhaps with calculated irony, says that there had been no plan to destroy the building. “While it was conceivable that tanks and other armored vehicles could be used to demolish the compound, the FBI considered that such a plan would risk harming the children,” the report says. Just what would constitute demolishing the compound the tome doesn’t explain, but it does report that if the tear gas effort failed, “walls would be torn down to increase the exposure of those remaining inside.” When walls are leveled, a point is soon reached at which there is no “inside”—but that was a point too deep for the review’s assessment. The Bureau’s Jericho plan was not the simple dream of officers in the field: among those who discussed it with Reno were FBI director William Sessions and acting assistant attorney general Webster Hubbell, a figure in the Arkansas scandals that were dogging the new president.

Reno was not an easy sell. According to the Justice Department’s report, she declared that she wouldn’t approve the scheme until she was assured that CS, the type of tear gas that the planners proposed to use, would not cause serious harm to pregnant women or young children. Her concern for the children was especially appropriate: Gas masks don’t fit their faces. The report states that two days later, at a briefing also attended by Sessions, Hubbell, and other Justice Department brass, a civilian expert from an Army research center in Maryland assured her “that although there had been no laboratory tests performed on children relative to the effects of the gas, anecdotal evidence was convincing that there would be no permanent injury.” The Justice report also says that Reno’s adviser told her that CS gas could not cause a fire.

CS is the common name for orthochlorobenzylidenemalononitrile, a white powder that manufacturers and vendors classify as a “lachrymator irritant”—a substance that causes tearing. It is, however, a bit more noxious than its designation implies. Named for the two American chemists who first concocted it in 1928, B.B. Corson and R.W. Stoughton, it is listed in manuals from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration as causing “irritation of eyes, skin, and respiratory system” and as corrosive to aluminum and magnesium. More than one hundred nations, including the United States, have banned its use in warfare, though governments are free to inflict it upon their own citizens. Manufacturers of CS gas warn against its use indoors, in part because heavy exposure to it has been cited as a cause of death in a report by Amnesty International. “Generally persons reacting to CS are incapable of executing organized and concerted actions,” a U.S. Army manual on civil disturbances points out, “and excessive exposure to CS may make them incapable of vacating the area. ” When burned, one manufacturer of CS cautions, its particles can give off lethal fumes.

Though her reservations about tear gas had been laid aside, Reno remained wary. She held another meeting in which she suggested a new tack: How long could Mount Carmel’s water supply last? The state of the Bureau’s information was recorded in a log; the March 20 entry notes, “an analysis of available information on water in the compound indicates most probably a limited supply to begin with, and reserves are very low. Replenishing the supply seems to be accomplished through techniques such as capturing rainwater.”

But Reno’s Washington advisers told her that they doubted the report, and at her request, the Bureau ran a check on April 15. It sent an airplane loaded with spy gizmos over Mount Carmel at night. “The rear water tank now appears to be full . . . This determination was based on the thermal image of the warm water in the tank,” its log said.

Reno’s point was tactically apt, the spy plane’s report notwithstanding. Even if the water tanks were full, they weren’t bulletproof, as the initial raid had already shown. They were punctured by gunshots on February 28 and could have been pierced again. The FBI had been told that, in addition to collecting rainwater, the residents were rationing water. If they were dependent on rainwater, nature would have been on the Bureau’s side: Summers in Waco are relatively dry. A full explanation of why the water-supply strategy went by the wayside hasn’t been published. Probably, Reno wasn’t fully informed. Afterward, in a congressional hearing, she said, “We explored but could not develop a feasible method for cutting off their water supply. ”

The attorney general requested a written proposal from the Bureau and, after perusing it on April 17, gave her approval for an assault that would begin on April 19 and extend over 48 hours. “The action was viewed as a gradual, step-by-step process,” the Justice Department’s report maintains. “It was not law enforcement’s intent that this was to be ‘D-Day.’ ”

The 48-hour plan for gassing Mount Carmel lasted about five minutes. At 6:02 a.m. on April 19, FBI logs show, combat engineering vehicles, or CEVs—M-60A1 tanks modified with thirty-foot booms and bulldozer blades for demolition duty—began punching holes in Mount Carmel and injecting CS gas through the holes into the building. This much was according to plan. But at 6:04 a.m., the Bureau’s logs say, people inside Mount Carmel fired upon the armored vehicles.

A clause in the written plan that the Bureau had presented to Reno called for an escalation if the tanks drew fire. The Justice report notes, “Under that operations plan, as approved by the Attorney General, ‘If during any tear gas delivery operations, subjects open fire with a weapon, then . . . tear gas will immediately be inserted into all windows of the compound using the four BV’s”—a reference to Bradley armored vehicles, ordinary combat tanks.

Janet Reno, watching the escalation of the assault on TV, was taken by surprise. Like a naive used-car buyer, the attorney general hadn’t checked the fine print on the contract that the FBI’s salesmen placed before her.

Reno, watching the assault from Washington on a television with special wire hookups, was apparently taken by surprise. The nation’s attorney general, the Justice Department report indicates, “did not read the prepared statement carefully, nor did she read the supporting documentation . . . She read only a chronology.” Like a naive used-car buyer, she hadn’t checked the fine print on the contract that the Bureau’s salesmen had placed before her.

The significance of the Bradley escalation turned on the kind of esoteric detail that only chemists and Bureau veterans—not a newly minted attorney general—could have known. The Bradleys were not equipped with hydraulic booms, as the CEVs were. They could not deliver gas as the CEVs did, from cylinders containing a mixture of carbon dioxide and CS powder mounted near the tips of their long booms. Bradley drivers could deliver tear gas only by shooting football-size metal or plastic canisters, called ferret rounds, out of a small port in the front of the tank. CS powder was suspended in the ferret rounds not in carbon dioxide but in a different chemical: methylene chloride, a petroleum derivative. The FBI assault force, in preparation for the Bradley-ferret option of its plan, had stockpiled some four hundred CS canisters in Waco.

Standard chemical reference books say that methylene chloride in its liquid state is practically nonflammable. But their texts do not picture the chemical as harmless. One reference, for example, reports:

Health Hazards: Eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritant. Toxic. Harmful if inhaled or absorbed through the skin. Narcotic in high concentrations. Metabolized by the body to form carbon monoxide. Products of combustion may be more hazardous than the material itself.

Fire and Explosion Hazards: No flash point in conventional closed tester, but forms flammable vapor-air mixtures in larger volumes. May be an explosion hazard in a confined space. Combustion may produce irritants and toxic gases. Combustion by-products include hydrogen chloride and phosgene.

Phosgene, the Encyclopaedia Britannica says, “is a colourless, extremely poisonous gas. . . . It first came into prominence in World War I, being used as an offensive poison gas.”

In short, methylene chloride, used in a confined space, threatened to create conditions conducive to fire, explosion, and death by poison gas. The CS particles could have ignited as dust does in grain-silo explosions. Manufacturers of CS powder warn against its use indoors because their chemists and attorneys know the dangers of CS and methylene chloride. So do most SWAT team operatives.

The effect of ferret rounds in indoor settings has for twenty years been an item of police lore. At least two incidents in FBI history point out the danger of using ferret rounds. In 1974 police officers and G-men surrounded a house at 1466 E. Fifty-fourth in Los Angeles that was occupied by members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, notorious for its kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst. On December 9, 1984, FBI agents cornered a right-wing fugitive named Robert Matthews in a house in Washington State. In both cases the FBI shot in ferret rounds, and in both cases the buildings burned rapidly to the ground.

At 11:40 a.m., about twenty minutes after the last of the ferrets was fired into Mount Carmel—long enough for vapor to form—the building went ablaze. In less than an hour, Mount Carmel was a smoldering ruin from end to end. FBI spokesmen, Janet Reno, and even the president would afterward insist that the occupants of Mount Carmel had set fire to their home, and in line with that presumption, most reporting about the cause of the fire has overlooked that as a result of the CS invasion, all the conditions for a fire were in place.

From the start, the residents of Mount Carmel had assumed that the siege would end in fire. Immediately after the initial raid, David Koresh had turned the secular side of his mind to predicting the government’s next move. “You’re going to smoke bomb us or you’re going to burn our building down,” he declared in a telephone conversation with the FBI negotiators who were working for a peaceful settlement to the standoff. Having examined the bullet holes in the front door and those he attributed to helicopter fire at several spots inside the building, Steve Schneider, who was Koresh’s closest aide, announced in early March that a fiery finish was in the interest of the federal besiegers: It would get rid of evidence. According to the version of the initial raid told by survivors, helicopters strafed Mount Carmel, and then ground troops fired through its closed front doors. The building’s roof and entrance, they said, bore proof of these accusations. “If you people don’t burn the building down . . . it would surprise me that they wouldn’t want to get rid of evidence,” Schneider told a negotiator on March 6. “If anybody wanted to even come here and burn the place down, kill all the people, what evidence would be left?” he asked on March 10. “If this building stands,” he admonished another day, “and the press get to see the evidence, it’s going to be shown clearly what happened and what these men came to do . . . So if you guys want, you can even be involved with them in burning this place down.” The negotiators, of course, denied any such intention.

Late in the siege, on April 13, Schneider mentioned to an FBI negotiator that the residents were reading by candle and lantern light. Houston attorney Jack Zimmermann, who went into the building during the siege, testified at the San Antonio trial that “almost every room had a Coleman lantern.” As protection against renewed gunfire, bales of hay had been brought from storage in the gymnasium and stacked against walls that faced outside. A negotiator recognized a hazard and asked, “Do you have any fire extinguisher systems?” Schneider wasn’t sure how many of the devices were on hand and, at a negotiator’s request, sent a resident to do a count. He reported that only one extinguisher was found. “Somebody ought to buy some fire insurance,” a negotiator replied.

The residents of Mount Carmel were not unnerved by the specter of a fiery finale. If God wanted to save them from the flames, they believed, He would find a way. Steve Schneider’s wife, Judy, reminded the FBI that the Book of Daniel reports that God saved Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the flames of a furnace, and on March 27, while discussing means of persuading the residents to leave, Steve Schneider had the following conversation with a negotiator:

Schneider: Well, you know what I think would work—well, I better not say that.

FBI: Go ahead, it’s your dime.

Schneider: I was just going to say, throw a match to the building, people will have to come out.

FBI: No, we’re not going to do something like that.

Schneider: . . . Some time when you have the chance, read Isaiah 33 about people living in fire and walking through it and coming out surviving.

On April 18, a listening device that the FBI had placed within feet of the front door captured snatches of conversation in which unidentified residents were discussing Scripture related to fire. “They can’t destroy us unless it’s God’s will they do,” one of the nameless speakers said. “Haven’t you read Joel 2 and Isaiah 13, where it says He’s going to take us up like flames of fire?”

But after one of the fire’s survivors, Jaime Castillo, read transcripts of these conversations, he explained, “A fire was expected, it was and is, but not that we of our own will could bring about such an event. God will eventually bring about that event.” Livingstone Fagan, a former Mount Carmel resident and theology graduate who was sentenced to prison in the San Antonio trial, attributes a similar meaning to the conversations: “They were just reviewing scriptures,” he writes from prison, “. . . regarding what happens when we are delivered and the Kingdom is set up”—an event that, Mount Carmel’s survivors believe, still lies in the future.

Bureau men listened to the discussions of fire relayed by the bugging devices on April 18 and presumed that the talk referred to plans for arson. But on April 19, the morning of the final assault, the Bureau did not surround Mount Carmel with fire trucks, as would have been appropriate. Instead the agency launched a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with forward-looking infrared radar, or FLIR, capable of determining when and where fire broke out. The equipment does this by inserting a circle onto an infrared videotape whenever a hot spot is detected. The purpose of the video was apparently to show that if a fire did break out, the Bureau didn’t ignite it.

The government’s fire expert, Paul Gray—whose wife now works for the ATF’s Houston office—finds in the FLIR tapes evidence that the fire broke out at 12:07:04 p.m. on Mount Carmel’s second floor. He and his assistants also claim that the tapes show three separate points of ignition in quick succession—an almost certain sign of arson, and the tapes indeed show circles around three spots in quick succession.

But lay critics, including the San Antonio jury, have seen that the first blaze spotted by the FLIR rig, and appropriately signaled by a circle, began at 11:59:16 a.m., not on Mount Carmel’s second floor but in its gymnasium, as a tank backed out of the room. The second-story fire was captured by television cameras two miles away and broadcast around the globe. The gym fire, clearly indicated on the FLIR tapes made from overhead, was out of the view of television lenses. Rather than multiple fire points, what the tapes show, critics argue, is that the holes the tanks had knocked into the building acted as flues, sweeping the gymnasium blaze down Mount Carmel’s hallways.

The controversy over ignition points almost always proceeds into another series of arguments about the sensitivity of FLIR equipment, the content of smoke clouds, the speed of the fire’s spread, and other technical, and unverifiable, details. To this mix of speculation are added interpretations of nearly unintelligible bugging tapes made early on the morning of April 19 from beneath the floor of Mount Carmel’s lobby. Transcripts of the murkily transmitted voices show residents saying things like “spread the fuel” and “fire around back.” One transcript by a forensic audio specialist renders the latter phrase as part of a longer one, “I want a fire around the back,” while another expert records it as, “There’s a fire around the back.” The dark spots of memory that remain with the fire’s survivors—loyal followers of Koresh and one government witness, Marjorie Thomas—do not resolve the discrepancy, around which a new industry has grown: Just as ATF agents have sued the Waco Tribune-Herald and Waco TV station KWTX for allegedly warning Mount Carmel of the February 28 raid, survivors of those who perished are suing the FBI for having sparked the April 19 blaze.

Whether or not, for theological reasons, David Koresh thought he had orders to burn Mount Carmel to the ground, as some of his accusers maintain, he recognized a tactical and wholly mundane use for flames: “Those tanks are not fireproof, you know,” he had warned the FBI on March 19. If on April 19 Koresh decided to repel the monstrous vehicles that had besieged his flock for 51 days, he did not have to send anyone outside—and into camera view—to fling Molotov cocktails. They presented themselves as targets by barging indoors.

About three minutes before the ferret rounds began breaking windows, tanks started crashing through Mount Carmel’s walls. Bureau spokesmen declared that the entries were made not to destroy the building but to inject gas into its inner recesses, and to provide openings through which the inhabitants could escape. During the siege, Mount Carmel’s two telephone lines had been reduced to one, which the FBI had connected to a ground line that had been tossed in to residents, who had connected it to a telephone in the building’s lobby. The Bureau’s spokesmen told the world that Steve Schneider had cut off communication by throwing the telephone outside when the teargassing began, but television footage and the Justice Department’s internal investigation indicate that a tank’s steel tracks severed the line, leaving Mount Carmel out of touch with the negotiators. Transcripts of conversations picked up by listening devices show that Schneider wanted to ask the Bureau to withhold its assault so that Koresh could finish writing his interpretation of the Seven Seals in the Book of Revelation—a request they had been making for days.

Rather than creating escape routes, the tanks that rammed Mount Carmel closed them. They demolished the stairways connecting the building’s first and second floors and also pushed debris over a trapdoor leading to a buried school bus whose door opened to an underground passage to the fresh air outside. Six women were found within a few feet of the trapdoor, dead of smoke inhalation; they apparently took their last breaths while racing toward the newly blocked underground passage. During an entry at high noon, one of the CEVs went into Mount Carmel’s cafeteria, where some three dozen women and children were huddled in a concrete room at the base of the residential tower. Though the Bureau’s spokesmen and the press called it a bunker, the room had been built years before to house Mount Carmel’s printshop. It contained the community’s walk-in refrigerator and its store of guns. The CEV’s boom apparently struck high on the wall of the room’s western side, sending chunks of concrete tumbling onto the heads of those cowering below. Though most of them were wrapped in wet blankets and towels—to protect them from tear gas—six of the women and children died from what the Tarrant County medical examiner’s office termed “blunt force trauma.” Forensic specialist Rodney Crow now says that these victims were crushed and suffocated “from the falling concrete in the bunker that fell on them.” But, in tune with the passions of the hour, several newspapers interpreted “blunt force trauma” as an indication that the victims were bludgeoned to death by their peers.

It is apparent from the accounts of survivors that some of the adults inside Mount Carmel preferred death to surrender, even death for their children. Some two dozen of the nearly eighty people inside died from gunshot wounds, including David Koresh and Steve Schneider.

Government witness Marjorie Thomas, who suffered third-degree burns over half of her body, was not one of those who accepted martyrdom. In a deposition for the San Antonio trial, she described the final moments of Mount Carmel:

The whole entire building felt warm all at once, and then after the warmth, then a thick, black smoke, and the place became dark. I could hear—I couldn’t see anything. I could hear people moving and screaming, and I still was sitting down while this was happening. Then the voices faded.

I was making my way out of the building, because it began to get very hot, and my clothes were starting to melt on me. . . . Before the fire had started, Sheila [Martin] Jr. was sitting on the step . . . I couldn’t see her. I was making my way towards getting out, and I trod on her, and I said, ‘I’m sorry,’ and her voice was very faint, and I couldn’t see her, and I could feel the flames . . . I saw a little bit of light. I made my way towards the light, and on doing so, I could see where it—it was one of the bedrooms. I could—the window was missing. I looked out. I don’t like heights, but I thought . . . ‘I stay inside and, and die, or I jump out of the window,’ so I put my head—my hands over my head and leapt out of the window.

While the tanks were rudely bringing down Mount Carmel, FBI chief negotiator Byron Sage and an assistant were attempting to calm those inside. Over the public-address system they said, “This is not an assault. This is not an assault. We will not be entering the building.”

Surviving residents say that in making their entries, the tanks knocked over lanterns and cans of fuel and crushed a pressurized tank filled with liquid propane, a volatile heating and cooking fuel. About the time that the fire got under way, transcripts show, the FBI agents who were broadcasting surrender orders over the public-address system began to ad-lib, adding to their prepared text exclamations such as “David—you have had your fifteen minutes of fame” and “Vernon is finished. He’s no longer the Messiah!” (Before he changed his name in 1989, David Koresh was named Vernon Flowell.) Television footage shows that after the conflagration began devouring Mount Carmel’s densest structures, CEV tankers, instead of merely standing by, may have used their bulldozer blades to push debris and remaining sections of wall into the blaze—destroying bits of evidence, as Steve Schneider had said they would. Ultimately, the heat was so intense that it ignited Mount Carmel’s flag, 25 yards away atop a steel mast. By the time fire trucks had chilled the building’s ashes, a new and victorious banner was flying in its place—someone had hoisted the flag of the ATF.

Unnoticed, and sometimes uncounted among the dead, were two fetuses, one full-term, the other seven months old. Both are believed to have been born as the result of an evolutionary reflex instants after their mothers, Aisha Gyarfas and Nicole Gent, expired. Gyarfas was the victim of a gunshot wound; Gent, of the crashing concrete. The deaths of their infants, who would have been viable had they experienced normal births, were the omega of the day whose alpha was the ill-advised tear gas raid.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- TM Classics

- David Koresh

- Waco