This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Marge Henson’s three bedroom ranch-style house in Southwest Houston is for sale. She doesn’t know where she’s moving; her husband’s employer won’t agree to transfer him and he doesn’t have any offers. But she doesn’t care. All she wants right now is to get out of Houston—fast.

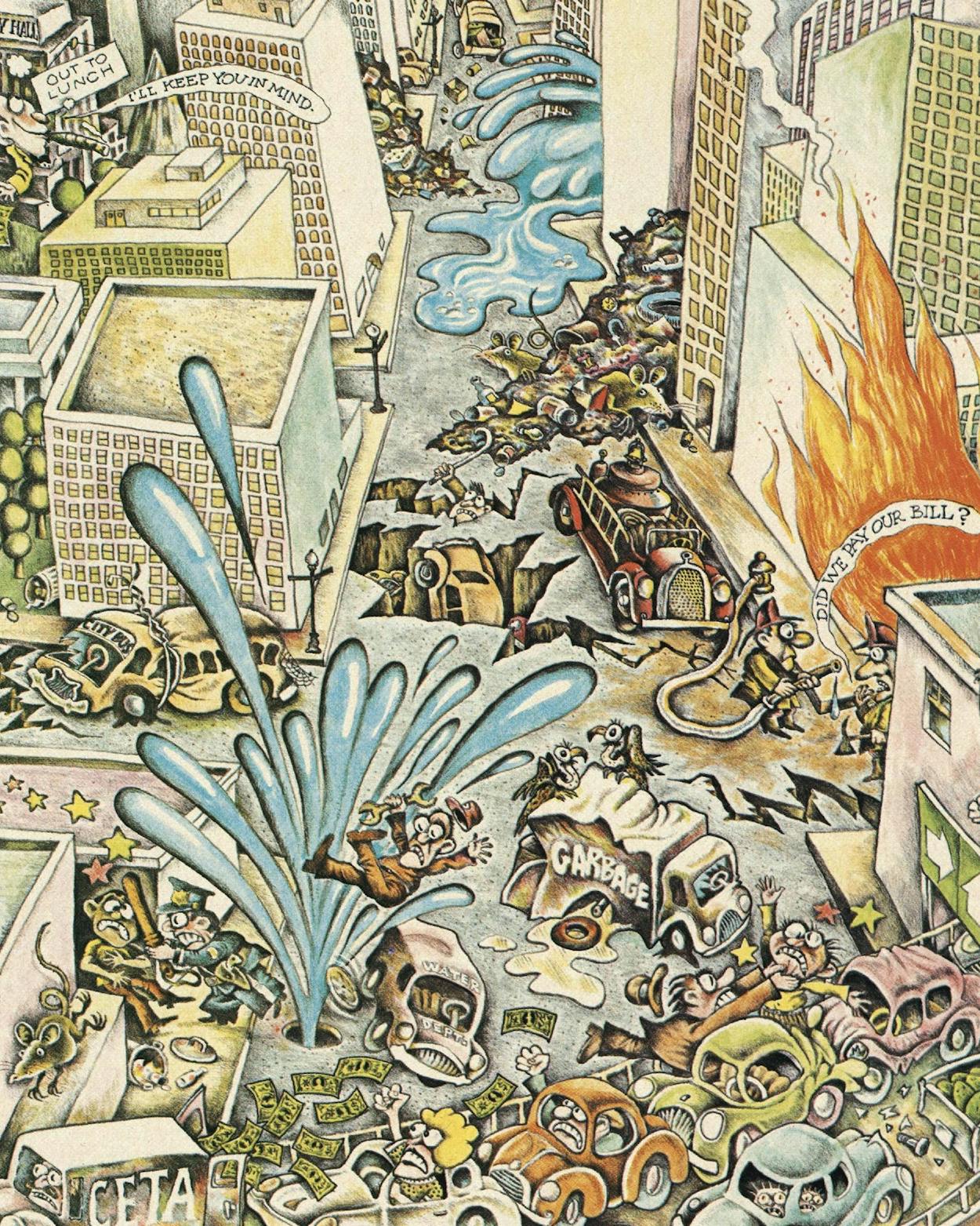

This summer was the worst time of Marge Henson’s life. All the basics of city life that one takes for granted everywhere but Houston—water in the pipes, garbage pickup twice a week, buses and police if you need them—could no longer be relied upon. No amount of puffery about the city’s booming economy and phenomenal growth could compensate for the paralysis of Houston city government that was becoming the dominant factor in her life.

On the day she made up her mind to leave town, Marge Henson slept through the alarm and got up two hours late—at 3 a.m. That left only two hours to soak the yard, the city having limited summer watering to the early morning hours to protect its woeful water system. At breakfast her husband was tense and irritable, and no wonder: he faced a ride on the MTA. The odds were overwhelming that the bus—if it came at all—would have faulty air conditioning and would be driven in a lurching fashion that has led transit officials to accuse drivers of sabotage. So why ride the bus? Because his car was in the shop, the victim of a gaping pothole.

Marge Henson spent the morning shopping—or at least what was left of the morning after she emerged from a giant traffic snarl at Chimney Rock and Willowbend, where the city hadn’t repaired a broken traffic light for seven months. In the afternoon she drove over by Hermann Park to talk about a family problem with her sister Helen. With their parents getting along in years, Helen had agreed to add a room and bath to her house and take them in—only to be told by city hall that because of inadequate sewage treatment facilities, no new toilets could be installed in the area. But, Marge noted as she neared Helen’s house, that didn’t prevent a high-rise condominium from going up two blocks away.

That night she attended a neighborhood meeting called to consider hiring a private security service, since average police response time outside Loop 610, even for emergencies, is upwards of half an hour. Back home, she put out the trash, fully expecting to bring it in again the next day when garbagemen failed to show up for the fourth time in a row. Her last act before turning off the lights was to set the alarm for 1 a.m. and the next day’s watering.

During this summer of discontent Marge Henson has become the typical Houstonian. Something is happening in Houston. Something is happening to Houston. Its current problems cannot be blamed on the usual ills that afflict cities everywhere—air pollution, urban sprawl, crime. Boomtown USA, the fifth-largest city in the country, the city its boosters like to call “the brass buckle on the Sunbelt,” is in deep trouble largely of its own making. The city is face to face with a disturbing and fundamental question: has the traditional bare-bones approach of local government, in many ways an essential factor in Houston’s success, at long last outlived its usefulness?

This is not to suggest that Houston is about to go the way of derelict cities like Cleveland and New York. Its bond rating is high and its economy robust. Houston is not ringed by incorporated suburbs and can add to its tax base by annexation almost at will. In a pinch it always has the option of annexing the Ship Channel industries. But if utter calamity is not in the forecast, a substantial degree of chaos seems to have become almost routine. As Houston has grown, from 938,000 people in 1960 to 1.75 million in 1980, its ability to deliver basic city services has not only failed to keep pace but in fact has deteriorated. Residents in newly annexed areas frequently must hire private companies if they want security service and garbage collection. It is true that Houston has always been a town that has preferred to get by with a minimum of help from city hall, and one reason services are poor is that taxes are low. But the real problem is that in this free enterprise capital of the nation, Houstonians aren’t even getting what little they pay for:

•Streets. Houston takes the cheap way out, electing to patch rather than resurface. As a result, the city filled more than 800,000 potholes in 1978, compared to Los Angeles’s 109,000. Things haven’t gotten any better since then: in 1979 Houston spent half as much on street maintenance as it did in 1969. Some streets are so bumpy and uneven, even in the most exclusive neighborhoods—Tanglewood Road comes to mind—that they should be put on stilts and moved to Astroworld amusement park.

•Parks. The city ranks an abysmal 140th nationally in park acreage per capita. Former mayor Louie Welch (1964–74), now president of the chamber of commerce, once said Houston didn’t need many parks because people have big yards.

•Water. Houston’s distribution system is hard pressed to deliver more than 400 million gallons a day. Dallas, with half a million fewer people, has a capacity of 515 million gallons. Houston rationed water this summer, blaming the statewide drouth, but Dallas, San Antonio, and Fort Worth did not have to cut back. The city loses a fifth of its water to leakage.

•Garbage. The city has no preventive maintenance program for its garbage trucks, so on most days about half the fleet is out of service. Exact numbers are impossible to come by because no one knows for sure how many trucks the city has; official estimates vary from 318 to 352. Collection crews staged a wildcat strike this summer to protest poor administration (the department head is a pharmacist with no managerial experience) and faulty equipment (when the trucks don’t run, workers aren’t paid). After the strike ended, it was hard to tell the difference—there weren’t enough functioning trucks to pick up the trash.

•Transportation. In theory, Houston isn’t to blame since this is now in the hands of the regional Metropolitan Transit Authority. In practice, however, Houston retains control because its mayor names five of the seven members on the MTA board. Moreover, MTA’s broken-down buses are largely a legacy from the city, which abandoned all maintenance in the lame-duck months before MTA inherited the system. As they did with the water problem, officials blamed summer heat for the failures, but on a day when MTA recorded 79 canceled runs, 65 late starts, and 163 breakdowns, San Antonio’s transit system had scores of 0–0–5 in the same three categories.

•Sewage. The City of Houston is the worst polluter in town, but it nevertheless refused to spend money on new sewage treatment facilities until the feds effectively barred further toilet connections in the older part of town. The new plant won’t be ready for a year or more; in the meantime, the city requires anyone who wants to put in a toilet to compensate by promising not to develop a vacant lot elsewhere. The effect has been to create a flourishing “white market” in toilets, with developers amassing and trading potential disconnects—a game beyond the means of ordinary citizens.

•Traffic. The basic difficulty, of course, is too many cars. But the city does little to help. It has no setback rules for buildings near major thoroughfares, nothing to prevent concrete canyons like Woodway west of Loop 610, where high rises jut skyward from the sidewalk. That destroys any chance of widening the street to absorb the additional traffic caused by the buildings. Then there is the traffic department itself. There are only three crews to put up and repair traffic signals; two work exclusively in the downtown area, leaving one for the rest of the city’s 550 square miles.

•Drainage. Motorists unlucky enough to be caught out during a heavy rain sometimes have to circle the city on raised freeways, waiting for flooded streets to clear before they can exit. Again, some of the problem is unavoidable—Houston is too flat and too paved—but that doesn’t explain why the city doesn’t require developers to use porous asphalt, not concrete, or insist that commercial developers control runoff from parking lots.

That is far from all. In truth, except for the library it is hard to find a city department that works. Tax? No properties have been reappraised since 1977. Some haven’t been looked at in twenty years. Public service? The granting of five cable TV franchises (see “Invasion of the Cable Snatchers,” TM, March 1980) is a model of government-by-favoritism. Health? The department collects scads of information but has neither the manpower nor the inclination to analyze it. City planning? The budget per capita is one fifth of Dallas’s, one ninth of Austin’s. In the past the department’s role has been mostly limited to approving subdivisions; this year, when it tried to branch out into unraveling traffic tangles like the Galleria, Mayor Jim McConn cut the desperately needed proposal out of the budget. Anti-poverty programs? Houston’s are notorious for squandering huge sums of public money with no tangible result other than delivering political payoffs to middlemen. A staff of 113 people in a housing rehabilitation program has managed to award but 71 grants in four years, a performance so poor that federal overseers were going to jerk the remaining funds if Houston didn’t spend the money faster. The solution was classic Houston City Hall: hire 97 more people.

How can this be? How can the populace that utilized advanced technology to put a man on the moon tolerate a government that can’t keep garbage trucks running? For the fact is that there is nothing accidental about Houston’s failures. They are the inevitable fruit of seeds sown long ago. Just about everything is wrong with Houston city government today—its structure, its personalities, its politics. But most of all, Houston today is a victim of its own traditions.

Sins of the Fathers

“Houston is overgrown,” a disgruntled citizen wrote in a letter to the Post, “seemingly blundering along without any policy or defined government management.” That was written in 1892, but it could have been dated fifty years earlier or later or, for that matter, yesterday; people have been complaining about Houston’s inert government almost since the first streets were surveyed in 1837. Houston’s form of government may have changed many times since the city first incorporated—strong mayor, weak mayor, city commission, city manager, and back to strong mayor—but the substance has changed very little. The basic themes are still the same.

One is growth: the first act of the first mayor was to increase the size of the town (and the tax base) ninefold. Another, however, is that regardless of how much Houston grew and how much money it managed to take in, no one had much to show for it. There were no paved roads in town until 1882, though Houston’s quagmire streets were infamous throughout Texas. The city dumped raw sewage into Buffalo Bayou and until 1887 took its drinking water from the same source. Houston built its first sewer system only under duress: Army engineers refused to dredge the Ship Channel unless Houston cleaned up the bayou—just as Houston started building new treatment plants in the 1970s only under the duress of the federal toilet embargo. Houston didn’t have a park until 1899, because it had no money to acquire one. Indeed, the city couldn’t even afford something as essential as a waterworks until 1906. But this perpetually destitute condition was a matter of choice: Houston’s taxes were the lowest of any major city in Texas.

No factor loomed larger in entrenching this low-tax-low-spend philosophy than Reconstruction. Houston’s Radical Republican mayor erected an ornate city hall at a cost of $470,000—about four times the city’s annual income—and plunged the city into hopeless debt. Even to pay the interest on the bonds required more money than the city collected in a year. This crisis totally strangled local government until 1885, and the city that has a AAA bond rating today was the bane of creditors a century ago, for it voted to repudiate the bonds. One thing did come out of those dismal years: Houston learned the lesson of profligacy, and it would not soon forget it.

For some, however, there were other lessons to be learned as well. How could the mistakes of the past be avoided? In 1912 a report to the city council documented the wretched state of Houston’s city services: one eighth of the needed pavement, less than half the necessary water service, few sidewalks, fewer sewers. That was the genesis of a flourishing movement for official city planning—a ministry whose idea of salvation was the issue that came to dominate local politics for the next half-century: zoning.

No doubt some voters saw zoning as nothing more than a pocketbook issue. Realtors, speculators, and property owners in deteriorating neighborhoods were generally anti-zoning, while downtown interests and the better residential neighborhoods were for it. But zoning also represented a departure from Houston’s tradition of laissez-faire government, and so it quickly assumed a much larger philosophical importance. Whether you were for or against zoning said something about your view of government—optimist or pessimist, Pollyanna or cynic.

It was no contest. Even such zoning proponents as Will Hogg, developer of River Oaks, and Jesse Jones, Houston’s most influential financier, couldn’t overcome the citizenry’s deep-seated doubts that their government was the best judge of the city’s future. Hogg failed to persuade the city council in 1929 and an associate failed in 1938. In 1948 the prozoners tried a referendum, setting up a titanic clash that pitted Jones against oilman Hugh Roy Cullen, downtown against suburb. Cullen called planning un-American and virtually called Jones a carpetbagger; Cullen won, better than two to one, and when the battle was fought again in 1962 with different leaders, the issue was settled: Houston would be the only unzoned major city in the country.

In retrospect Cullen was right, Jones wrong. No amount of zoning ordinances would have prevented the flight of commerce to the suburbs. Zoning would not have stopped satellite downtowns like the Galleria and Greenway Plaza, but it would have forced them to go much farther out, changing the city’s character. In any event, the way to protect the city’s interests is not through zoning but through annexation—to ensure that when downtown businesses move away, they remain part of the tax base. In 1948, the year of the Jones-Cullen confrontation, Houston doubled in size; eight years later it doubled again.

The ongoing zoning fight did Houston a terrible disservice, for it polarized the issue of how the city would deal with growth. The anti-zoners proved to be right: with the help of deed restrictions, the marketplace did provide a rough form of zoning. Glue factories did not spring up in River Oaks. But the long zoning fight obscured what should have been the real issue—construction controls, not land use—and the slightest attempt at regulation drew anguished screams that the city was trying to zone. Even today, Houston has no subdivision ordinance (the planning commission has its own rules, but they are unofficial) or control over drainage, setbacks, or traffic in commercial developments. It was a major struggle to pass a parking ordinance requiring apartments to furnish spaces instead of relying on city streets. Zoning remains such a dirty word that in 1977 some city council members had misgivings about prohibiting X-rated movies and adult bookstores from operating near churches or schools. The planners fought the wrong battle, and for that mistake, like others in its past, Houston is still paying.

The Network

The headquarters of the Houston Chamber of Commerce is located high up in one of the downtown steel-and-glass office towers, allowing its president to look down on city hall from his corner suite. From his desk, former mayor Louie Welch, still one of the most influential people in town, can see two of the four clocks on the sides of the building. They are not synchronized, and the thought is inescapable that in Welch’s heyday, they would have meshed to the second.

Even his former foes remember the Welch years with some nostalgia (except for blacks, who will never forgive his support of police chief Herman Short), for he was the last mayor who could make city hall work. Welch was skilled at both politics and administration, which made him an ideal person to fill the top job in a strong mayor system. He was his own city manager; he seemed to know everything that was going on in every department. Leonel Castillo, former city controller and an unsuccessful candidate for mayor in 1979, says clerks in the controller’s office used to talk about getting calls from Welch concerning such details as whether a particular voucher had been paid.

Welch knew all the tricks, too; he was a master at the rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul shenanigans that let the city appear thrifty in the eyes of the voters without cutting services. His masterstroke came after he won the mayor’s seat by promising to roll back a water rate increase. He did it, all right, by charging his own parks and fire departments for water they used. The departments, of course, had to pay with tax dollars, so the public paid the same amount in the end, but less visibly.

The mayor of Houston has more unfettered power than any other officeholder in the state. He has powers a long line of Texas governors have coveted: the ability to remove appointees, to propose the budget, to shift funds from one budget item to another. He is a member of the legislative body and appoints the municipal judiciary. All department heads report directly to him, not to some board or commission.

Welch used the potential to its fullest: he understood city hall the way Lyndon Johnson understood the Senate. Even so, it took him a full term to figure out the Network—the unique way city hall works to thwart the power of a mayor who can’t find a way to beat it. “I spent my second term firing everybody I hired during my first,” Welch said, only half jokingly.

If Welch was the LBJ of Houston politics, the current occupant of the office, Jim McConn, is the Dolph Briscoe. But to understand McConn’s shortcomings, it is first necessary to understand how the Network—and because of it, city hall—operates.

The one factor most essential to the Network’s survival is the utter absence of accountability in Houston city government. This is a common problem in politics these days, from the courthouse to the White House; even so, Houston stands out. Civil service is far too broad, covering everyone but the department heads and their deputies. Upper-level management is filled with deadwood that cannot be chopped. Bill Cape, director of the city’s biggest department, public works, under Welch and successor Fred Hofheinz, once groused that he could double the efficiency of his department by cutting the payroll one third. But, he went on to say, “there’s no way in the world you can get rid of them’’ because they can appeal to a sympathetic Civil Service Commission. Following her first year in office, city controller Kathy Whitmire suspended an employee after building up a thorough file on his shortcomings. The commission scolded her because all of the problems occurred in one year and the employee had been on the job for five.

Houston makes no provision to reward employees for performance. Civil service rules call for regular employee evaluations, but in practice few departments bother. The city budget provides almost no money for individual merit raises, and recently the mayor’s office has been trashing what few requests do dribble in.

Lacking a way to get rid of what Cape used to call “civil service freeloaders,” the city has flirted with insolvency by sweetening the pot to tempt longtime employees to leave. City policy enables employees to cash in accumulated sick leave back to the day of their original employment with the city at their current salary. When former city treasurer Henry Kriegel left to run for a similar post with Harris County, he received $56,000 in sick leave benefits and claimed he was entitled to more. The city’s total liability is $101 million, about one seventh of the current budget.

Ah, yes, the budget. In a space-age city, it is still stone-age. Budgeting is largely done by the incremental method, which is a sophisticated way of saying that if the city has 10 per cent more money to spend this year than last, every department gets 10 per cent more money. Never mind what they plan to do with it—apparently that’s strictly their own business. Budget analysis is one of the best ways to hold the bureaucracy accountable: departments are forced to set goals and then at the end of the year own up to how close they came to achieving them. Houston does nothing of the sort. There is no attempt to measure performance.

The current system, such as it is, is great for department heads, who have almost complete freedom within the personnel limits set by the council. But it is terrible for anyone (like the mayor) who wants to know where the money is actually going. To make matters more difficult, the city generally doesn’t adopt its budget until well into the calendar year—June 13 this year, in August one year during the Hofheinz regime—which means that for much of the year, there are no written guidelines at all.

Welch tried to set up a modern budget management office. When computers started to become popular toward the end of the Welch years, many department heads—too many—went out and bought their own. Suddenly the city had an excess of incompatible software. A consultant recommended a central management and information system (MIS) and even loaned the city an expert for a year to set up the new department. By this time Hofheinz was mayor, and he decided that the new division should become a super department of management information and budget. The first test was to computerize water bills and make them monthly. Disaster! It turned out that no one in the water department had read a meter in years, and by the time the mess was solved, the borrowed expert’s year was up and the new department still wasn’t off the ground. Now the city has come full circle: McConn gave departments the go-ahead to get their own computers. They are safe from scrutiny again.

Another aspect of the Network that places it beyond the control of a mayor is the revolving-door policy. Something of the sort has raised some concerns in Washington: people go to work for the government, learn how an industry works, then leave to work in the industry, sometimes returning to lobby the agency they left. It’s a good deal cozier in Houston, where it is not uncommon to find former, and even future, colleagues in engineering, accounting, and law firms on opposite sides of the bargaining table. Take this summer’s electric rate negotiations, where the city swallowed a 100 per cent hike for street lighting and an increase in residential rates, while industrial users got a break. The head of the city public service department: Bill Earle, who came to city hall from the Butler, Binion, Rice, Cook & Knapp law firm. Attorney for the industrial users: Jonathan Day, who went back to Butler, Binion from, yes, city hall—he was Fred Hofheinz’s city attorney. (Butler, Binion has become the firm for doing business with city hall, taking the mantle away from Fulbright & Jaworski by recruiting Bob Collie, McConn’s first city attorney.) If the need is not law but traffic engineering there are two choices: Walter P. Moore & Associates has the former city traffic director; Wilbur Smith & Associates supplied the incumbent.

The political big shot is as integral a part of the Network as the revolving door. Looking out a north window in city hall, one can see a massive monument to how the Network works—and how city hall doesn’t. At one time the city planned for the area between city hall and the post office to be transformed into a civic center complex surrounding a mall. But when the Astrodome and Astrohall sprang up on South Main, the downtown-oriented Jones interests began pushing for a downtown convention hall. The city promptly scrapped its plans and plunked the Albert Thomas Convention Center into what was to have been open space. The haste was ill advised: the center turned out to be much too small.

When a political big shot is involved, the Network’s policy seems to be to ask no questions. So when the Host Hotel at Houston Intercontinental Airport wanted more favorable lease terms in exchange for agreeing to expand, they wisely turned matters over to Fulbright & Jaworski attorney Oliver Pennington, Mayor McConn’s campaign finance chairman. Sure enough, nobody from the city even bothered to check the impact of Host’s proposal before it reached the city council. It turned out that Host wanted to reduce the city’s share of room revenue from 36 per cent to 7 per cent. But that came out only after McConn’s opponent for reelection, Councilman Louis Macey, asked questions. Otherwise the lease would have slipped through the cracks.

Money Talks

When all else fails, the last resort of the Network is, alas, that money talks. Houston’s government is not corrupt in the manner of Northeastern cities, where construction is a closed shop and you can’t get a building permit unless you use the right contractor and the right union. But enough has come to light over the years to say that Houston exceeds any of its Texas rivals in grand jury investigations of city employees.

Only in Houston could two high city officials openly admit to acting as bagmen without suffering any adverse consequences. One was Cape, the czar of public works, who used to call in developers at election time and tell them how much each owed the mayor’s campaign treasury. “I took envelopes and delivered them to the mayor,” Cape told the Chronicle in 1977, taking care to add that no one ever got a favor from him in return. No doubt Cape would still be public works director today had he not died in 1977 after choking on a piece of meat at Tony’s. The other self-confessed bagman was Gene Gatlin, a senior mayoral aide in the last three administrations, who said he frequently delivered contributions to councilmen. One incident involving an envelope stuffed with $1000 in cash was probed by a federal grand jury.

For much of 1979 the city council could have held its sessions in the federal courthouse, so often did council members appear before the grand jury. The city’s purchasing agent, McConn’s very first appointment, pleaded guilty to extorting money from city contractors. McConn himself was called to explain what he termed a “sheer coincidence”: a $6000 shakedown by the purchasing agent on the same day McConn asked him for a $6000 loan to cover the mayor’s Las Vegas gambling debts. In all this smoke there was apparently no fire, for the grand jury handed down no further indictments.

Outside the council chambers, nowhere in city hall is influence peddling more rampant than in the mammoth public works department, the nerve center of the Network. Public works is responsible for the big-money city services—building permits and inspection, water, sewage, drainage, and street maintenance—and the rulings of second- and third-echelon employees can make or break people who want to do business with the city. Often the decision-making process is a bureaucrat’s dream: completely arbitrary, unguided by any standards or procedure. First-term city councilman Lance Lalor, who represents the Rice University–Medical Center area, has tried and tried to figure out on what basis the department awards the coveted sewage “availability letter” that allows new toilet connections. “If you know your way around public works, you get the letter,” Lalor says. “If not, you don’t. If you want anything from public works, you need a friend there.”

Last year the public got a rare glimpse into how things work in the department when the city attorney’s office investigated a longtime city employee for accepting favors from two businessmen who dealt with public works. In one incident the employee, Calvin Fenley, enjoyed free use of a Lincoln Continental supplied by the owner of a company that installs water mains and fixes leaks. At the time Fenley managed a division responsible for installing water mains and fixing leaks. What explains the most about the Network, though, is that Fenley’s supervisor knew about the car for several months before the story became public but did nothing about it.

In Dallas the appearance of impropriety is not regarded so casually. Several years ago a fire department inspector whose job involved making certain that street contractors kept a lane open for fire trucks was handed a bottle of whiskey on the job site. He turned it down, but the contractor walked over and put the bottle in his car anyway. This time the inspector didn’t object. He was fired for accepting a bribe.

Calvin Fenley’s fate? He was promoted. Fenley is now deputy assistant director of public works.

Because of the strength of the Network and the long tradition of inept city service, the real vitality in Houston city government isn’t in city hall at all, but rather in a few highly skilled businesses that deal with the city on a regular basis—engineers, accountants, contractors. The engineering firm of Turner, Collie, & Braden (Collie is the father of former city attorney Bob Collie) does so much work for the city that it is sometimes known as “the other public works department.” Bob Braden is the closest thing Houston has to a city manager. The firm is the chief water and sewer engineer for the city, the leading member of a consortium that handles the city’s airport planning, and the local partner in a major overhaul of the city’s tax structure. A similar situation exists in solid waste management, where Browning-Ferris Industries does all the planning.

These firms are more than consultants. Consultants are retained to look at problems on a one-shot basis; in Houston their responsibility is a continuing one. In effect, Turner, Collie, & Braden and the other city advisers are really extensions of city hall. They initiate policy, telling the city when it is time to raise charges and suggesting improvements like inventory control procedures. In the latter case, the city didn’t listen: to this day not a single piece of property in city hall—desks, chairs, art works, typewriters—is identified as belonging to the city, and in many department maintenance centers there is no inventory of parts.

Obviously the delegation of public functions to private firms has a serious downside. Sometimes decisions are made for the wrong reason, as in the location of Intercontinental Airport. Informed opinion advised putting it on the west side of town, but when a group of local businessmen offered the north side site to the city at their cost, the deal was closed. Now the city is looking at a west side airport anyway. The other problem is conflict of interest: when Turner, Collie, & Braden gets a contract to project the city’s long-term water needs, it knows that it will eventually get the engineering contract as well—there is no bidding on professional services. Still, it is indisputable that the system of government-by-contract runs better than the rest of city hall. That has a lot to do with the Network, but it also has a lot to do with Jim McConn.

The Vanishing Mayor

There was a time when Jim McConn wanted to be a doctor, but he ended up in sales—and later, politics—instead. It was the right choice: after all, a poor mayor can’t be sued for malpractice. And any doubts that McConn wasn’t a natural salesman should have been dispelled by the bravado of his reelection slogan last fall: “We already have a good mayor.”

In some ways the slogan had a point. One has to wonder whether even a Louie Welch could hold Houston together today. Since Welch’s last term the number of city employees has soared from 13,300 to 17,000 and the budget has jumped from $267 million to $740 million. McConn is better at citywide politics than Welch was (no power blocs are mad at him) and he more than holds his own in city council battles, even though mayor-council politics requires far more skill in these days of fourteen councilmen and single-member districts than in the Welch era of eight councilmen elected citywide. Unfortunately for McConn, his strengths are obscured by his weaknesses, for his shortcomings lie in exactly the areas most vital to how the city runs.

One problem—some would describe it as a blessing—is that McConn is never around. This year alone he has junketed to Guatemala, Jamaica, Mexico, Germany, and Israel, plus Washington, Seattle, Southern California, and on several occasions, New York. His response to criticism was to stop publishing his agenda. Even when he’s in town McConn much prefers the ceremonial aspects of his job to the administrative. One top staffer says McConn often talks longingly about Dallas, where the hundreds of small decisions that in Houston pile up on the mayor’s desk are the responsibility of a city manager. In September McConn recruited former Fort Worth city manager Rodger Line for his staff, but it is too early to know whether that will make any difference. In the long run, Houston mayors will have a hard time recruiting city management professionals because mayors up for election every two years can’t offer much job security.

If a mayor isn’t going to run city hall himself, he has to make decisions fast and rely on his staff to carry them out. McConn, however, hates to tell people no; in the words of a former executive assistant, “The last person to see him always wins.” Aides have learned to stall for time, like a basketball team running down the clock for a last-second shot. In one typical fight—between an aide and a department head over a minor budgetary point—the aide won, lost, then won again, and at last word the budget manual was going to have to be recalled. A major furor erupted over veteran executive assistant Gene Gatlin, the bane of younger staffers because he knew how the Network ran and wouldn’t share his knowledge. McConn decided to send him to the aviation department, relented, changed his mind again and exiled Gatlin, only to recall him six months later.

Houston’s organizational chart is very simple: every department head reports directly to the mayor. There are no deputy mayors or supervisors to help out; the only buffer is the mayor’s staff. But it was a year before McConn specified which staffers were responsible for overseeing which departments. Even now the staff rarely meets as a unit, and the department heads have been convened only twice. The mayor’s office functions exactly the way the rest of city hall does: it responds only to emergencies.

The inevitable result is that the power of the mayor’s office has dissipated. The main beneficiary for a time was city attorney Bob Collie, in part because lawyers can always find an excuse to get involved in anything and in part because McConn always trusted Collie, a member of McConn’s campaign steering committee, to look out for the mayor’s political interests. For a time Collie was known around city hall as the deputy mayor, but when he left to practice law the power vacuum reappeared, to remain unfilled—except, of course, by the Network.

Nothing is likely to change before the end of 1981, when Houston holds its next mayoral election. The trouble is that nothing may change even then. A lot of names have been mentioned as possible candidates—attorney (Butler, Binion, of course) Steve Oaks, Texas Secretary of State George Strake, Councilman Lance Lalor, and controller Kathy Whitmire—but in the past Houston’s best political and managerial talent has not been interested in city hall. As in New York, the mayor’s office is not the place for anyone with higher political ambitions, as all the glitter candidates are said to have. Perhaps a council dark horse like John Goodner, or some unknown millionaire (the next race is likely to cost $1 million) will emerge. Or even McConn: he was written off last year after developer Walter Mischer, Houston’s foremost political kingmaker, was reported to have said, “I like my mayors dumb, but not that dumb.” But no one better came forward, and Mischer ended up in McConn’s corner. It could happen again, for while McConn hasn’t done much to arrest the decline in city services, he is hardly responsible for it. Larger forces are going to make life hard for any mayor.

Foremost among them is politics. Houston is much more politically diverse than it was in Welch’s time. McConn was elected by a coalition of developers (who supplied the money) and blacks (who supplied the votes). He took office owing more things to more people than Welch did. A disturbing number of department heads—solid waste’s, for one—have gotten their jobs for political rather than professional reasons. Future mayors will face the same pressures.

Even Houston’s heralded economic success works against it. With the economy booming, the city is an employer of last resort. From engineers to mechanics, good employees are hard to recruit and hard to keep; workmanship is a problem in every department.

At the same time, the city’s century-old political consensus is breaking down. Of the thousands of people moving to Houston every month, many come from zoned Northern cities with a high level of services and, of course, high taxes as well. The newcomers aren’t likely to have a longtime Houstonian’s tolerance for potholes and water rationing, and it will take a lot of tax increases to approach what they paid back home. Where else but Houston would a mayor say, as McConn did early this year, “I heard enough in the campaign to think people may really want the potholes fixed”?

All the news is not dismal, certainly. There’s a chance that in ten years or so, Houston, for all its problems, could actually be a better place to live. The hated sewer moratorium will be lifted when a new treatment plant opens. The MTA’s dilapidated buses will be replaced by rail lines. The economic base will stay strong because the city, in a rare display of foresight, has secured enough surface water for another half-century of growth. Even the embarrassing shortage of parkland is being rectified, thanks to a privately run give-a-park-to-Houston campaign. But the basic irritants—the potholes, the leaky water lines, the flooded streets—are likely to be around as long as Houston is. They have almost come to be viewed as part of the city’s essential character, symbols that say: this is one place in America where government is not top priority.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston