August 6, 2009, seemed to be a day like any other on the Yearning for Zion Ranch. Recent rains had doused the flower beds, vegetable garden, and fruit orchard, and rosy-cheeked women in full-length, pastel-colored dresses were crouched on their hands and knees, pulling out weeds and setting them in little piles. In the dairy, a slight young woman listened to hymns as she stirred cheese in a large metal vat. The carpentry shop was abuzz with men in long-sleeved collared shirts sawing wood to make cabinets, chairs, and cradles. Boys bounced down winding gravel roads in trucks and on heavy machinery. It was a pastoral scene of industriousness like those you might see in Hildale, Utah; or Colorado City, Arizona; or Pringle, South Dakota; or any of the other towns where the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a polygamous Mormon sect with about 10,000 members, had established religious communities.

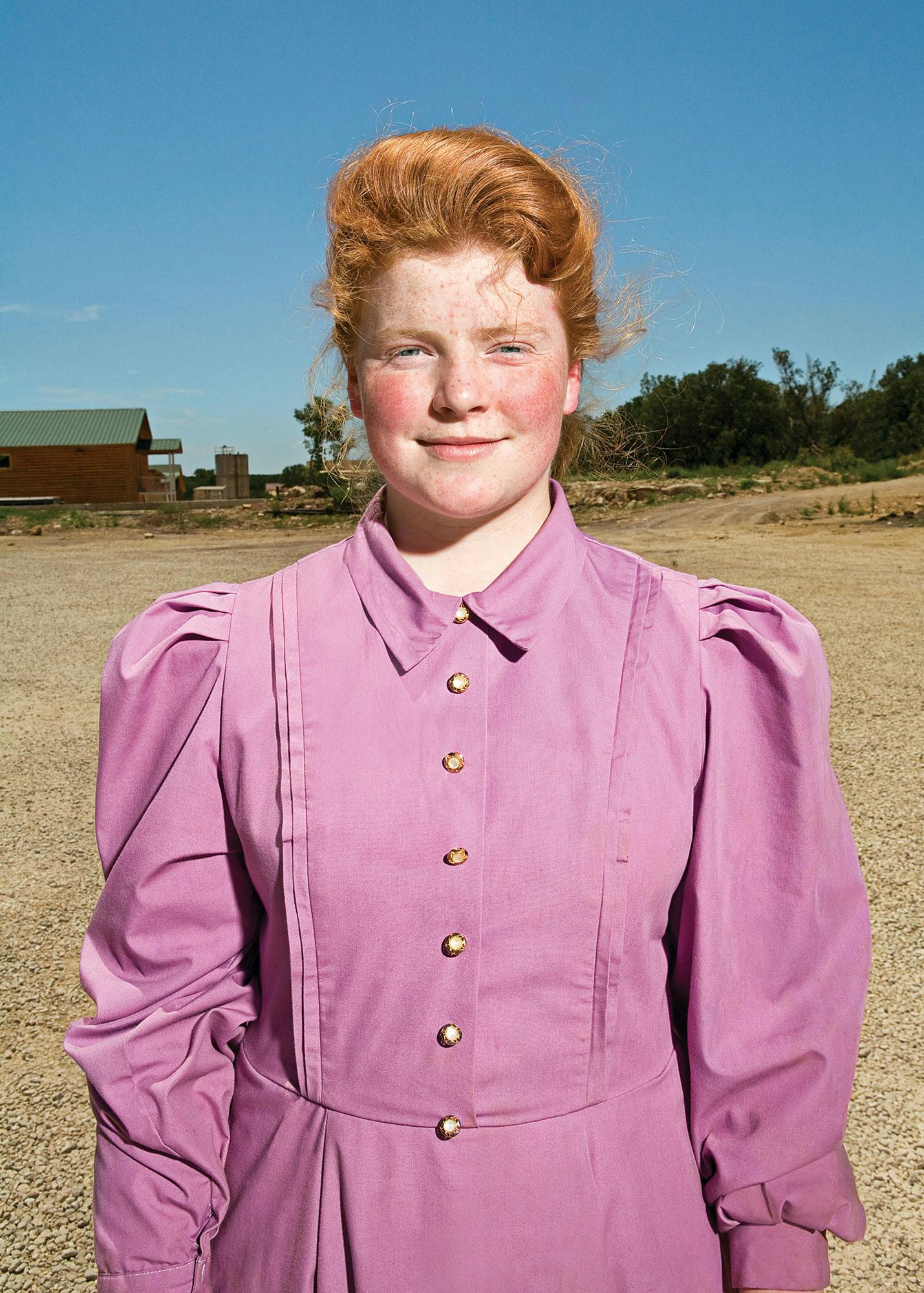

Less apparent in the tranquil setting was a powerful undercurrent of joy: Merrianne Jessop had arrived the night before. There was no “Welcome Home” banner, no party; such theatrics would have been out of character for these humble, quiet people. But the feeling was there all the same. “Right now there seems to be a little bit of relief in the air,” said Willie Jessop, the unofficial FLDS spokesman (Jessop is a common surname in the FLDS), as he drove me around the 1,700-acre spread outside Eldorado. Merrianne, a spunky fifteen-year-old with red hair, was happy to be back with her family on the ranch. She was quick to joke, rolling her eyes every now and then for laughs, tossing her head as a light West Texas breeze ruffled her lavender prairie-style dress.

The past year had been an ordeal. In the spring of 2008, the ranch was raided, and the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services had removed 437 children, including Merrianne, after a local domestic abuse hotline received a call from someone claiming to be a sixteen-year-old FLDS member. The caller’s report of underage marriage and sexual abuse triggered a massive investigation that led to an epic child custody battle, the largest in U.S. history. The Third Court of Appeals ruled that the removal of the children had been unwarranted, and a chastened DFPS returned the kids to the ranch, though the department continued to investigate the cases. Merrianne’s was the last to be settled.

Her mother, Barbara Jessop, and her new court-appointed guardian, Naomi Carlisle, who is also an FLDS member, seemed giddy as they looked at her. All three of them were confident that the Lord was on their side and that the state had had no right to intervene, never mind the mountains of evidence obtained during the investigation, some of which plainly showed that the FLDS had married young teenage girls to much older men. Never mind that the church’s prophet, Warren Steed Jeffs, was himself in prison for being an accomplice to the rape of a fourteen-year-old. Never mind that criminal charges, including sexual assault and bigamy, were still being brought against twelve men from the ranch. When asked about the upcoming trials, which start on October 26, Merrianne shrugged. “The truth will prevail,” she said.

Anyone who has followed this case from the beginning might easily find cause to doubt that statement. In the eighteen months since the children were first removed from the ranch, so many conflicting reports have been presented that even close observers have had trouble following the thread. First, there was the stunning revelation, just days after the raid, that the initial call to the abuse hotline had been a hoax, phoned in by a woman in Colorado with a history of making false reports. Then the DFPS was forced to admit that its original statement that more than half the teenage girls on the ranch were pregnant and that a suspicious number of children had broken bones was wrong; apparently the department had been categorizing adult mothers as underage, and the number of broken bones was about average for a group of four hundred children. The sympathies of the public, which had initially tended to fall with the state, quickly swung to the polygamists, who claimed they had been attacked merely for being different. “You think you’re persecuted?” Larry King asked Willie Jessop during a May 22, 2008, interview. “Larry, it is our history,” Jessop told him. The FLDS had been vindicated, and many people were left with the impression that an overzealous DFPS had screwed up.

But that was certainly not the story told by DFPS workers. They pored over materials taken from the ranch—photographs, marriage certificates, census logs, diaries—and were convinced that in some cases, action needed to be taken. In Merrianne’s case, a marriage record indicated that her father, Fredrick Merril Jessop, who essentially ran the ranch operations, had performed a marriage between Merrianne and Jeffs at the YFZ Ranch in July 2006, when Merrianne was twelve years old and Jeffs was fifty. The girl would later tell caseworkers that this couldn’t have been a crime because “Heavenly Father is the one that tells Warren when a girl is ready to get married . . . He is only following the word of Heavenly Father.”

This antagonism between the law of the land and the word of God is an old and fierce struggle, particularly in the United States, which was founded on the principle of religious freedom. The FLDS, in fact, is in some ways a product of this conflict. In 1878, in a landmark case involving the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Supreme Court ruled that plural marriage was illegal. The LDS eventually banned the practice, and a group of fundamentalists broke away, in part to continue “celestial marriage.” The group established its own communities, with a large concentration in a place called Short Creek, which encompassed the adjacent towns of Hildale, Utah, and Colorado City, Arizona. In 1991 some of the descendants of these fundamentalists founded the FLDS.

Thus far, the conflict between the State of Texas and the FLDS has played out on the battleground between government and religion, state and family. Familiar legal arguments, technicalities, and political postures and platitudes were standard components of the story line. Only now, a year and a half after the raid, with all the children out of state custody and the trials of the twelve men set to begin, will the spotlight return to the crimes allegedly committed on the YFZ Ranch. And as more of the evidence is unveiled, the question will undoubtedly arise, Who thought it was safe to return these kids to the FLDS, and why?

Back in 2002, before his sect had even settled in Texas, Warren Jeffs had predicted a troubled road ahead. At a meeting with the priesthood that year, he introduced a member named Sam Barlow, who explained that “there was a combined effort by the attorney general in the state of Arizona and the attorney general in the state of Utah to investigate and interfere with the principle of marriage by revelation.” Barlow said that laws pertaining to underage marriages had been passed with the specific aim of bringing the FLDS into conflict with the judiciary. “They call it ‘sexual conduct with a minor,’ ” Barlow said. He advised the membership to remain strong. “We’re being confronted by something that we haven’t seen before,” he said. “Brethren, if you’re the person that gets targeted, let’s get close to the Lord, let’s be united, stand together, and you be the one that takes a hit without flinching.”

Fundamentalist Mormons had for decades operated outside the mainstream of American society—and even the mainstream of Mormon society—but scrutiny from authorities was new to this generation. The last serious confrontation with law enforcement had occurred in 1953, when Arizona cracked down on polygamists in the infamous Short Creek raid. More than two hundred children were removed from their homes. But much to the surprise of Arizona governor John Howard Pyle, the public’s response was outrage. Pyle lost his reelection bid, and the polygamists seemed to have earned a free pass.

That began to change in the early 2000’s. In 2003 Utah attorney general Mark Shurtleff met with Merril Jessop’s former wife, Carolyn, who had recently left the fold. By the end of the meeting, “Mark’s aloof, professional demeanor had shifted to one of sheer outrage,” Carolyn says in her memoir, Escape. It was extremely rare for Shurtleff to talk to someone like Carolyn, whose seventeen-year marriage to one of the most powerful men in the FLDS had given her rare insight into the inner workings of the church. “After I talked with Carolyn,” Shurtleff now likes to say in speeches, “I realized that I had been elected to do a job, and I couldn’t ignore my responsibilities, even if it resulted in costing me my career.” Not long after this meeting, the Utah authorities convicted a Hildale sect member—a police officer, no less—for bigamy and for having unlawful sex with a sixteen-year-old girl he had married.

Shortly after the police officer’s conviction, the FLDS bought land in Eldorado and started building the YFZ Ranch. It was an ideal place for the sect’s new home. The area was sparsely populated, with just 2,736 people in all of Schleicher County. At that time, Texas’s age of legal consent for marriage was fourteen years old, with a parent’s permission. (The marriageable age was increased to sixteen in 2005 in response to the FLDS relocation.) There was even an allegedly polygamous group in the area that hadn’t been prosecuted: the House of Yahweh, about 130 miles up U.S. 277, in Abilene.

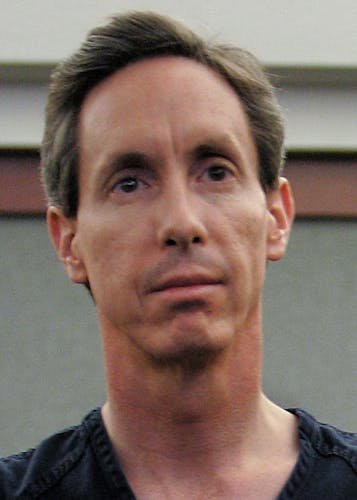

Warren Jeffs was a relatively new prophet of the FLDS at the time. He had assumed the role in 2002, after the death of the previous prophet, his father, Rulon Jeffs. A tall, slender man, Jeffs warned often of the imminent, dire consequences that would befall the unfaithful, a designation that he often found cause to apply to members of his own flock. Elissa Wall, a former FLDS member, recounts in her book, Stolen Innocence, that one day while Jeffs was on a brief trip away from Short Creek, some church elders erected a monument to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Short Creek raid. An inscription on the memorial read, “The Prophet Leroy S. Johnson stood on this site with the people and met the raiding police officers. He later declared the deliverance of the people in 1953 was one of the greatest miracles of all time.” When Jeffs returned to Short Creek and saw the monument, Wall writes that “he was livid” and accused the people of partaking in “idolatry.” “Raising his hand in the air,” Wall writes, “our prophet told us that the land of Short Creek would now be ‘cursed.’ ”

In the years that followed, Jeffs cast out members who were unworthy of salvation and selected members for the new promised land: the YFZ Ranch. Construction had already begun on the parcel, arousing the curiosity and suspicions of the locals. “We’d heard rumors around town in late 2003 that a group from Utah was buying a local ranch here and it was going to be a hunting retreat,” says Randy Mankin, the owner and editor of the Eldorado Success newspaper. But in March 2004 Mankin received a phone call from a woman named Flora Jessop, a former member well-known within the FLDS community for her scornful accusations. “I didn’t know Flora Jessop, had never heard of her, and had never heard of Warren Jeffs or any of this stuff. And she starts telling me this really bizarre tale about polygamy,” Mankin says. “I thought somebody was pulling my leg, because the biggest news the weekly paper covers involves the commissioners.”

As the building continued, a local pilot, J. D. Doyle, set up a Web site where he posted aerial photos of the YFZ land. His images found an unintended audience in out-of-state FLDS members who had been tithing and wanted to know how their money was being spent. Doyle began receiving e-mails asking, “Where is my money going? I want to see pictures.” Other members wrote that entire buildings were disappearing from Short Creek and reappearing in Doyle’s photos. (“Not kid-size buildings either,” Doyle says.) Doyle flew over the ranch three or four times a month, fascinated by the diligence of the people. “The compound changed so radically,” he told me. Pointing to a photograph on his computer, he explained, “I flew there one week—nothing there. The week after, it was a full-grown orchard. A full-grown one! It’s like, where the hell did that come from?”

Jeffs wrote in his “president’s record” (a kind of daily diary) that the work on the YFZ Ranch would bring the church closer to God. He paid close attention to the construction of the temple and complained to Merril Jessop when he saw that the men weren’t working on the project past midnight. The members needed to show a passion in their devotion and stick together, for even this place could be forsaken. Jeffs wrote, “They must qualify soon for the fulness of Zion, or there will be a cleanup at that place.”

Back in Arizona, the authorities were nipping at the sect’s heels. In August 2005 Jeffs, who was already wanted for sexual conduct with a minor and conspiracy to commit sexual conduct with a minor, was indicted again, on similar charges. Eight other FLDS men had also been indicted. “The Lord expects us to obey the word of God above all,” Jeffs wrote, “no matter what the laws of the land declare; and we stand with God and Priesthood.” He proclaimed that any man who testified at his own trial could be found a traitor against God and the priesthood.

By the fall of 2005, the temple at YFZ was nearing completion, and gardens, an orchard, a hay barn, and a dairy had been built. But Jeffs would not enjoy the sect’s new home for long. In May 2006 the FBI placed him on its Ten Most Wanted list of fugitives, and a few months later his Cadillac Escalade was pulled over in Nevada. He was arrested and a year later found guilty of two counts of being an accomplice to rape and sentenced to prison for ten years to life. But his dedication to the church remained strong. “Great blessings await the faithful,” he told a group of family and friends in the Mohave County jail, in Arizona, on March 26, 2008. “Thus great tests and trials and great experience is coming upon the people.”

Three days later an employee at a domestic abuse hotline in San Angelo, which is forty miles north of Eldorado, received a telephone call. The caller identified herself only as Sarah. She whispered into the phone so softly the worker could barely hear her. Sarah was hesitant to give any information. She’d pause for such long periods of time that the staffer had to ask if she was still on the line. The girl hung up and called back several times. With some patient prodding, Sarah revealed that she was sixteen years old, had an eight-month-old baby, was married, and lived at the YFZ Ranch, where her husband abused her. The hotline staffer wrote her report, and it was passed along to the office of Schleicher County sheriff David Doran.

Doran had been cultivating a friendly relationship with the people on the YFZ Ranch since they’d moved to the area. He had even visited the property about twenty times, at their invitation. After receiving the tip from the hotline, he called in a Texas Ranger named Brooks Long; by April 3, district judge Barbara Walther had signed a search warrant for Sarah Jessop Barlow and her alleged abuser, Dale Barlow.

At six-thirty that same evening, Long pulled up to the ranch’s tall white gates with the signed warrant. Two law enforcement cars were waiting for him there. By that time, Sheriff Doran had already made a phone call to Merril Jessop to let him know what was going on. A few FLDS men came out to meet the officers at the gates. The conversation was low-key. A large team had surrounded the 1,700 acres to be sure no one fled the area. There had been no indication that the FLDS were violent people or that they had a stockpile of weapons (they did not), but law enforcement took no chances. A drone aircraft flew overhead, monitoring the situation. An armored personnel carrier was standing by. Texas Ranger captain Barry Caver, now retired, was in charge of the operation. He had been involved in both the Branch Davidian and the Republic of Texas standoffs. “I had a lot of things in the back of my mind that I’ve seen go bad, and I did not want that to happen to me or under my watch,” Caver says, explaining his tactics. “This was not my first rodeo.”

Angie Voss, a supervisor for investigations at Child Protective Services, arrived at the ranch entrance after sunset, around nine, with nine caseworkers. (CPS is a division of the DFPS.) Jessop said that while there was no one at the ranch fitting the description of a sixteen-year-old named Sarah Barlow, he would allow the CPS team to interview girls at the schoolhouse.

Voss and her caseworkers began talking to the girls, one group at a time, but almost immediately she noticed a pattern of deception. “I was finding that the girls would switch their names,” she would later testify. “They would use a different last name than they had previously reported, [or] wouldn’t give a full name.” Caseworkers seemed to be getting a lead on girls who fit the description of Sarah. But when the second group of girls was interviewed, Voss said, the conspiracy seemed to build: Suddenly not one of the girls knew her own date of birth. And there were signs that evidence was being destroyed. When Voss walked into a lower level of the schoolhouse, she saw a large shredder with the light still glowing red. Slices of paper were dangling from the machine, and two big bags nearby were stuffed with tattered documents.

By three in the morning, Voss realized she was in a bad situation. Her caseworkers had interviewed about 25 girls, and while they still hadn’t found Sarah, they were beginning to discover what seemed to be a systematic practice of underage marriages. They were obliged to follow through on this information, but doing so was no easy task. “Some were forthcoming with information, some weren’t,” Voss testified. “They switch kids. They deny their children. I’ve encountered a few young girls that initially said they didn’t have children at all, and then later reported they did.” As the night wore on, she decided to remove 18 girls.

The investigation continued the next day, and by Friday night, she had grown fearful of the mounting tensions between the ranchmen and law enforcement. The previous night FLDS men had been standing in the schoolhouse stairwells, watching the caseworkers; some had video cameras. On Friday they climbed the trees to do countersurveillance with night-vision goggles. “I think what also added to my concern was that law enforcement had begun mobilizing a SWAT team, a tank, so you know, here I am trying to help children be safe in what felt like a very unsafe environment,” she said.

Before long Voss decided to take all the children. Her position was that every child was indirectly related to these alleged victims of abuse and could not be interviewed properly at the ranch. “The little boys, the babies, the girls—what I have found is that they’re living under an umbrella of belief that having children at a young age is a blessing, and therefore any child in that environment would not be safe,” she testified.

Removing the kids was not an outcome Long had expected. “I told Ms. Voss, I said, ‘I want it in writing,’ ” Long recalled, in an interview with Jeffs’s attorneys last year. “I said, ‘Angie, just trust me, because the potential for violence will escalate when we start taking these kids away. And so I want a document where your agency is asking my agency to do this, because this was not our plan. And so she wrote it out, and of course by then I go to my supervisors and I say, ‘Red flag! This thing is changing.’ ”

Over the next week, the children were removed from the ranch, and concerns escalated. Ultimately, the State of Texas removed 437 children; 139 women went voluntarily to be with their kids, leaving only 60 or 70 men and elderly women on the property. The women and children were housed at five different places in Eldorado and San Angelo; at some of them, the scene was not pretty. In the tight sleeping quarters of one of the facilities, they were vulnerable to a circulating bout of chicken pox. The food provided by volunteers was radically different from the normal FLDS diet and caused digestive upsets among the members. Worse, there was little trust between the mothers and the DFPS workers. Determining the age of the children was crucial, but when family members supplied birth certificates, the DFPS workers often questioned the documents’ accuracy. According to an employee from the Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, which was called in to help manage the situation, a few state workers treated the women and children harshly. One MHMR employee stated that a group of children had been forbidden to wave to friends and family across an open field. Those who continued to wave were threatened with jail time.

The discovery of Sarah, meanwhile, was hardly a triumphant moment for the DFPS. A Texas Ranger finally tracked her down in Colorado, only to find that she was not an FLDS member at all. Her real name was Rozita Swinton. She was a 33-year-old woman known for making false reports to police and women’s shelters around the country. Investigators searched her apartment and found research notes about the FLDS. Dale Barlow, who was a real person and a member of the sect, was not married to her. Swinton was charged with false reporting to authorities, a class three misdemeanor.

Before the public could even finish its collective gasp at the prospect of 437 children being taken away from their families on the basis of a hoax, DFPS commissioner Carey Cockerell presented a shocking briefing to the Senate Health and Human Services Committee. In an apparent attempt to recover some credibility, he claimed that half the girls aged fourteen to seventeen were pregnant or had already had children. This turned out to be untrue. He also noted that a lot of the kids had broken bones, but it was quickly pointed out that the number was probably average for a group of that many kids in a rural environment. The situation was rapidly becoming a PR nightmare for the DFPS. In mid-April, when the department began removing the mothers, the previously reclusive FLDS spotted an opportunity and opened the ranch to the news media to tell its side of the story. Newspapers all over the country ran photos of sobbing women who’d recently been torn away from their children.

On April 18 Judge Walther ruled that the children should remain in state custody, and the kids were moved out of temporary facilities and placed in homes all over the state. Over the next few weeks, the DFPS took a beating. “Here we are sixty days later, and they’re still treating everyone like a bunch of abusers,” one attorney connected to the case told the San Angelo Standard-Times. “This is about winning at all costs for them,” said an FLDS attorney. “This is out of control.” Willie Jessop told the paper that the YFZ Ranch members had ordered five hundred to six hundred voter registration cards and intended to “put people in office with integrity.”

The political dimension had become apparent to the governor’s office as well. In the days following the raid, it had received a wave of e-mails and phone calls. Governor Rick Perry, who appoints the leadership of the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) and the DFPS, had initially been supportive of the department’s actions, though much less vociferously than Arizona governor Pyle had been during the 1953 raid on Short Creek. Nonetheless, history wasted no time in repeating itself; as with Pyle, the public response was decidedly unsympathetic to the state’s cause. A Public Information Act request shows that the governor’s office kept a running tally of the feedback. By April 23, the office had received 560 calls and voice mails complaining about the raid and just 44 supporting the state’s actions. Angry e-mails also came fast and furious. “It’s the Mormons this time, but it could be you next,” read one e-mail. Others voiced similar concerns:

“If you do nothing to protect these rights, you can be assured that you will not have my vote now or ever in the future.”

“Has Texas become the new Communist China?”

“What happened to religious freedom?”

“These look like women trying to be good mothers, who want to isolate themselves from what they feel is a secular and amoral society. Is that now illegal?”

On May 22, 2008, the FLDS had its first victory. The Third Court of Appeals ruled that Judge Walther had lacked adequate evidence in ordering hundreds of children to remain in custody and that she had abused her discretion. Some lawyers applauded the decision, but child law experts grumbled that it was terrible. The Center for Public Policy Priorities’ executive director, Scott McCown, a retired state district judge who had presided over thousands of child abuse cases in his career, told the House Committee on Human Services this year, “What the Court of Appeals in essence was saying is, ‘Yes, there was a bunch of underage girls, and yes, they’re married, and yes, some of them are pregnant, but the department didn’t prove that in some courthouse somewhere in the world some judge hadn’t consented to the marriage.’ Well, that’s an impossible standard to meet.” John J. “Jack” Sampson, the director of the Children’s Rights Clinic, at the University of Texas at Austin, told me he concurs. “I thought [the Third Court’s ruling] was awful,” he says. But this was not an opinion widely shared in the media, which by this point had latched on to the notion that the state had bungled the operation.

Chastened, the DFPS released a statement saying it would work with the office of Attorney General Greg Abbott to determine the state’s next steps. This was a key moment in the case. Abbott had initially been publicly supportive of the DFPS’s response, but it was unclear what direction he would take now. According to the Texas constitution, “the Attorney General shall represent the State in all suits and pleas in the Supreme Court of the State in which the State may be a party.” But legal experts say that Abbott actually had three options: He could have forbidden the DFPS from taking its case to the Texas Supreme Court; he could have told the department to go alone; or he could have gone as its champion. At first it was reported that Abbott’s office was going to fight for the DFPS. After the department filed a writ of mandamus with the Texas Supreme Court, arguing that the Third Court had abused its discretion, a Supreme Court spokesman received word that the attorney general’s office was considering filing a brief. But hours later, the spokesman was told that that was no longer the case. Jerry Strickland, a public information officer for the AG’s office, explained, “I think that information came from a misstatement by a clerk at the Texas Supreme Court. I wouldn’t read too much into that.” The Supreme Court spokesman, Osler McCarthy, says he was only repeating what he was told.

Regardless of the procedural circumstances, knowledgeable appellate lawyers say Abbott’s silence was thunderous. By not sending a brief, he was effectively telling the Texas Supreme Court that there was a good reason for his office not to get involved. What happened? “DFPS was represented by counsel,” explained Strickland. “Therefore, it was not necessary for us to respond on their behalf.” Unnecessary, perhaps, but not insignificant. Could Abbott, who is eyeing a run for the Senate or for lieutenant governor next year, have been concerned about losing votes on the issue? Criminal charges against the fathers were one thing, taking kids from their mothers another—even if the abuse was systematic and even if some of those mothers had seen no problem in marrying off their underage daughters. “The AG’s office thought it would be good publicity, and it turned out to be bad publicity, so they punted,” says Sampson, the Children’s Rights Clinic director.

The DFPS was left isolated and ultimately unable to prevail. On May 29, 2008, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the Third Court of Appeals had not abused its discretion. The children were going home. Striking a new, conciliatory tone, the FLDS released a four-paragraph pronouncement saying that the church would not preside over any underage marriages, though it was unclear whether this declaration truly came from the group’s leadership. Willie Jessop told the Salt Lake Tribune he was unaware if Warren Jeffs had made any contribution to the statement at all. Nonetheless, the DFPS eventually took credit for the announcement, implying that its actions had changed the behavior of the FLDS.

The department was at a crossroads. While the court rulings had terminated the temporary custody of the children, the investigations were ongoing and the individual cases could still result in a range of outcomes, anything from nonsuits (essentially dropping the matter entirely) to termination of parental rights. But the Supreme Court, the Third Court of Appeals, and the public were now aligned against the DFPS. And so, of course, were the parents and children.

When the department attempted to fight back, critics took it as a sign of desperation. One photograph introduced at a hearing showed Jeffs kissing a twelve-year-old girl on the mouth. The girl’s brother, on the witness stand, told the court, “It seemed a little wild to me . . . but you see a lot more wild things than that driving down the streets of the city at night. I do not consider a girl kissing a man sexual abuse.” When the girl’s sister-in-law took the stand, she said the kiss was “inappropriate” but that “everyone has their free agency.” FLDS supporters declared the introduction of the photo a sleazy attempt to shape public opinion. Jeffs, they said, was only one man, and he was already in prison.

Not long after the Supreme Court’s ruling, a white-haired, soft-spoken family law expert named Charles Childress came to work for the DFPS. Childress was nearing the end of an impressive career that had included work at Bexar County Legal Aid, the Texas attorney general’s office, and the Children’s Rights Clinic. The DFPS had sought to bring him in to help with the cases, but Childress had initially turned down the offer. Retirement was beckoning (though for a man like Childress, “retirement” meant going to Saltillo, Mexico, to study Spanish and Mexican law). But as weeks passed and the cases stalled, he reconsidered.

Childress’s job was to represent his client, the DFPS, as the cases were litigated. His first day in charge of the department’s legal direction was July 23, 2008. Investigations were still under way in the majority of the children’s cases. Childress immediately had the cases broken down by family groups so staffers could decide which children were in the least amount of danger. “My position was, nonsuit the minor characters,” he says. “They believe in polygamy, which is a crime, but I can live with that as long as they’re not forcing the daughters and sons into it.”

But as Childress’s investigators combed through the evidence and reported their findings, he became alarmed. The documents acquired from the raid offered a wealth of revealing information. In particular, there was something called the Father’s Family Information Sheet: Bishop’s Record, which amounted to a Rosetta stone to the family structures at the YFZ Ranch. Filled out in 2007, these self-reporting census pages identified the father of each family, along with his wives, his children, and their ages and residences. Childress quickly recognized a set of unsettling facts: Thirty-seven men living at the ranch one year earlier had 132 wives and 332 children. (These numbers reflect the records that have been released publicly; actual numbers may be higher. If there is a sheet on Warren Jeffs, for example, that has been withheld.)

Other evidence raised more questions. There was the disparity in the ratio of teenage girls to teenage boys, for example. No one could explain why, in the twelve-to-seventeen-year age group, there were almost twice as many girls as boys. And then there was the white bed. Investigators’ photographs taken in the YFZ Ranch temple show an adult-size bed with railings that appear to fold up like a crib’s. On the bed’s rumpled linens, investigators said they had found a long hair. A document that Childress had not seen but was obtained by TEXAS MONTHLY appears to be instructions for the construction of a similar bed. It describes a bed “covered with a sheet, but it will have a plastic cover to protect the mattress from what will happen on it.” It also described “padded sides that can be pulled up that will hold me in place as the Lord does His work with me.” What in the world was going on here?

Childress commuted every Monday to the DFPS office in San Angelo, spent the week there, and then returned to his home in Austin. He scoured the documents and reports late into the night, looking for the clearest possible picture of the FLDS lifestyle. Interviews that had been conducted with the mothers and children were far from reassuring. Girls told caseworkers there was no age requirement for a celestial marriage. When a Child Protective Services caseworker told Merrianne Jessop that if a thirteen-year-old girl was impregnated by a forty-year-old man it was considered sexual abuse—even if the two were spiritually married—Merrianne looked disgusted. She insisted that the marriages were “pure.”

The investigators’ stories contained similar accounts of women who were baffled by the scrutiny. One of Warren Jeffs’s wives didn’t see why caseworkers were concerned about her daughter, who had been married to a 34-year-old man a day after she’d turned fifteen. The mother told a representative of the Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) program that she didn’t consider her daughter a victim and did not understand why her daughter couldn’t visit with her new husband. After all, said the mother, she liked her new son-in-law.

Not every interview was as candid. Witnesses to the interviews say that some members seemed to be controlling the others. When one girl who said she had a ten-month-old child was asked her age, she looked at her husband, who told her, “You are eighteen.” The girl then informed the investigator that she was eighteen. Texas state representative Drew Darby, of San Angelo, told me, “I saw what apparently was a nine-year-old boy and his mother talking to a CPS worker. The boy took his fist and hit his mom in the stomach, then made the motion of twisting his mouth with his hand as if he were locking his mouth with a key. I saw that.” When a CASA representative visited the house of one woman, her daughter videotaped the meeting—but not to keep tabs on the interviewer. After the mother asked the CASA representative if they could speak outside, the girl followed them with the camera, saying she would leave them alone “only if she [her mother] will remember what not to talk about.”

Childress urged action. A methodical man, he zeroed in on the department’s pleadings. The official state forms, which Childress himself had designed when he worked for CPS in 1997, typically present a range of possible outcomes. The department begins by asking for temporary custody while the investigation is being conducted. Depending on the conclusions of the investigation, the DFPS may recommend reunification with the parents, which is always the first choice, or, in more-serious cases, placement with relatives or other suitable adults. In the most serious cases, the DFPS can call for termination of parental rights so that the child can be adopted. “That is just standard pleading,” Childress told me.

But in the FLDS cases, the state didn’t follow the usual procedure. For some reason, the department chose not to include the possibility of terminating parental rights, meaning that any child that the DFPS thought was in danger would not be eligible for adoption but instead placed in foster care till age eighteen. Childress thought this strategy had tied the department’s hands, because, even in the serious cases, it was difficult to argue that “it was in the best interest of the kids to be in foster care until they age out,” he says. He wanted adoption on the table for the most egregious cases, but he was not in a position to change the pleadings without approval. Approval never came, and no one within the DFPS would tell him why.

In September 2008, Childress set a few deadlines. “I must know if you are going to allow me to pursue the plan that I have laid out,” he told DFPS staff, “which is to winnow it down to those people who are not cooperating, who fail to understand the impact on the kids.” As time went on, however, he wasn’t given an answer. He wasn’t sure why the powers that be were hesitating. He wasn’t even sure who was making the decisions, but the lack of communication was disconcerting. He told a few staffers, “I thought you hired me to take what we have and get the cases to trial. I didn’t know you were hiring me just to win my good name and take some of the pressure off so you could bail out.”

As Childress waded through mounds of paperwork, he began to understand just how disorganized the state’s case was. One box, holding a hodgepodge of evidence, was simply titled “Documents.” The quantity was overwhelming, and according to a source close to the case, the loads of material available to the DFPS lawyers made up only 7 percent of the evidence acquired from the ranch, with the remainder held back for the criminal trials.

Searching through the materials, Childress also learned more about Warren Jeffs, who during his time as prophet had been a meticulous record-keeper, registering his daily thoughts and actions in various dictations and priesthood records. He traveled with scribes who would stay up at night to capture any stray words he might utter in his sleep. Some of the dictations were curious. For example, in August 2005, while on a road trip across the U.S., Jeffs wrote, “The Lord has had me go to every state in the United States on the main land; forty-eight states, in kicking the dust of my feet off as a witness against them. In every state and every major city we passed through, we have delivered that city and state over to the judgments of God.”

His descriptions of his experiences make him sound like a time traveler from the 1800’s. While on the road, the Lord directs him to go to a tanning salon “and get sun tanned more evenly on their suntanning beds that have the lights.”

In Boston the Lord tells him to “mingle with the rich where there was a live band.” While visiting Louisiana, he notes that he is “having to go into hiding among one of the most wicked people on earth. This is a marvelous experience.” (St. Louis, apparently, wasn’t as marvelous: “Truly St. Louis is a dark and wicked place,” he wrote. “It must be destroyed.”) Along the way, he “sought the heavenly gift to ride a motorcycle.”

Childress discovered that even while Jeffs was on the road, he had total control over the lives of his church members. He was a theocratic dictator who meddled in the daily lives of his followers on both macroscopic and microscopic levels. He named their babies—even renamed children entirely. Once in a while, he’d reassign members to different families, cruelly testing the faithfulness of the men by “sealing” their families to other men. The men had no recourse but to repent from afar and hope that they could come back into the prophet’s good graces.

Jeffs was supremely confident, for the most part, in his revelations. When one girl balked at his order to marry her cousin, he wrote, “I said, ‘Well the Lord wants you to get married anyway.’ Afterwards I realized they were not blood cousins. The Lord knows what He is doing.” He could be manipulative. In one instance, he considered blessing a church member, then later altered his plan. He needed to marry off the man’s daughter first and determine if the man’s reaction made him worthy of approval.

Childress took careful note of the numerous references in Jeffs’s diary to underage marriages. At times Jeffs told fathers that he would be marrying off their young daughters without delay. “I dropped the girl off, and then had [the father] stay in the truck. I informed him that the Lord had told me that his daughter should be sealed to me for time and all eternity, and she is being gathered at this time while it was possible before the enemy could stop this marriage.” Jeffs married the girl a few hours later. Other fathers weren’t fortunate enough to receive notice. One sixteen-year-old’s parents weren’t told of their daughter’s wedding, since they “could not keep the Lord’s confidence.” And on July 27, 2006, in the same ceremony in which he married his own daughter to an older man, Jeffs married Merrianne Jessop. “There was sealed Merrianne Jessop to Warren Steed Jeffs,” he wrote. “That’s me!”

More worrisome to Childress was that even though Jeffs had been in prison since late 2006, his power had hardly flagged. Investigators found numerous letters in which Jeffs continued to direct the sect. He made calls that were broadcast over speakerphone to the members. He asked to be informed if members were too social in the kitchen. He warned one woman to overcome her laziness; another had to beware of her vanity. “Send me a list of the older unmarried daughters of Brother Merril Jessop and Brother Wendell Nielsen and who their mothers are and their exact ages,” he wrote. “Remind me of any marriages the Lord appointed in the record that have not been done.” And remember, he said, “Keeping the Lord’s confidence is life.”

Childress wasn’t terribly impressed with the state leadership’s understanding of the situation. “Going up to the governor, none of them had any idea what was going on,” he says. “They had no clue.” As he worked through the cases, he says, all the department saw was numbers. “ ‘The department is losing two hundred some-odd cases!’ That’s what was all in the news,” he says. Nonsuits were not “losses,” a subtlety overlooked in most accounts. Having formed a clearer picture of family structures by way of DNA testing, the DFPS was identifying the individual circumstances of each family and coming up with specific tasks that needed to be done, such as psychological evaluations or parenting classes. By mid-September, more than 250 children’s cases had been nonsuited.

As the months wore on, Childress went down to Austin to attend several meetings and explain his approach. One meeting included Albert Hawkins, the Health and Human Services commissioner; one included representatives from the attorney general’s and governor’s offices. Childress said he wanted to take some cases to trial. “They’d ask, ‘Well, can you guarantee us it will win?’ ‘No, there’s no such thing as a guarantee in a jury trial,’ I said, ‘but I’m pretty doggone certain that a West Texas jury hearing what all these people have been doing the last ten years is gonna be real reluctant to send these kids back to be raised by Warren Jeffs,’ ” Childress says. “I didn’t get any feedback . . . I think they just frankly lacked the courage.”

And so, on October 23, Childress quit.

People close to the cases had by this point suspected that anyone who wanted to pursue Childress’s course would get the same results. The day Childress left, Debra Brown, the executive director of the Children’s Advocacy Center of Tom Green County, sat down to write a letter to Governor Perry. “Child Protective Services seems determined to sweep this case under the rug and call it quits,” she wrote. “CPS recently nonsuited most of the families and now has only ten cases involving thirty-seven children remaining. . . . We have a goldmine of evidence corroborating abuse of children and need to act upon it now, as we will never have this opportunity again. This situation is only going to get worse.” She received a reply dated November 13 from Beth Engelking, CPS’s director of special projects. “I was surprised by many of the issues raised in your letter to the Governor,” Engelking wrote, “as you had not previously raised these same issues as a concern in any of our previous meetings.” Brown, who says she was never shy about her opinions, was stunned. “She had been in these meetings with us where we’d go over case X where we’ve got this problem and this problem,” Brown says. “She was sitting right there.”

While several people interviewed for this article suggested that the DFPS received pressure from its superiors to nonsuit even the extreme cases, Brown said that Engelking made a point of taking responsibility for the decisions herself. She called a meeting with some of the interested parties in San Angelo. “Beth Engelking told us that it was her decision to start nonsuiting these cases,” Brown remembers. “I’m not saying the kids should have never been returned, but we had legitimate concerns and questions on about thirty-five cases.” Brown said that Engelking had struggled with the cases but told the group, “I think this is in the best interest for these children and this organization, and I think this is the right thing to do.”

Brown wasn’t the only person concerned by the more problematic nonsuits. Charles Childress’s replacement, attorney Jeff Schmidt, was also disturbed, as were some attorneys representing the children. In fact, a few attorneys involved in the cases met with the governor’s office to address the issue, though it is unclear if they made a strong impression. According to state records, not a single e-mail was exchanged between the governor’s office and the HHSC, the DFPS, or CPS from October 1 to November 20, 2008. Brian Newby, who was Perry’s chief of staff until mid—October 2008, says that CPS lawyers and the attorney general’s office spoke with the governor’s office but that the governor’s office didn’t indicate a specific preference on which strategy to pursue. “We followed the advice of our lawyers, CPS, and attorney general lawyers,” he says.

Schmidt didn’t last long. A few days after replacing Childress, he was transferred to Corpus Christi. The DFPS said that he disagreed with its decisions and could no longer represent it. Schmidt was outraged. In an administrative complaint Schmidt filed on November 5, 2008, he stated that the DFPS legal unit was “in possession of evidence that supports aggravating circumstances on many of these cases. Even though these facts exist, the DFPS is still refusing to allow their attorneys to amend the live pleadings to allow for termination of parental rights.”

The department stood firm. Schmidt received a reply from the new DFPS commissioner, Anne Heiligenstein, explaining that “the decisions in these cases were made only after careful deliberation and consultation with DFPS executive management, HHSC, and the Attorney General’s office. The decisions were made with a conscious consideration of the needs of the children, the professional assessments of the families, and the viewpoints of experts in this department regarding the best interests of the children.”

Debra Brown didn’t see it that way. She told me, “A lot of the workers I worked with felt like they just didn’t have a say.” And Schmidt felt that the department’s response defied logic, since some of the FLDS men had been indicted for crimes. “Children’s lives and welfare are at stake,” he wrote in a later response, “and it appears all the Department is willing to do is deny any wrongdoing.”

After Schmidt left, the department filed nonsuits on almost all the remaining cases. “The thing I’m angriest about,” said Susan Hays, who was an attorney for several of the YFZ children, “is you spend twelve million plus, traumatize hundreds of kids, then drop the real cases? They ran it like a political campaign. How deep a hell do you burn in for that?”

This past summer, Commissioner Heiligenstein told me that if allegations of abuse resurfaced at the YFZ Ranch, she wouldn’t hesitate to intervene, though she believed such a scenario was unlikely. In her opinion, the FLDS had learned from this ordeal that Texas was intolerant of underage marriages. “It is our belief that future abuse to these and other children will no longer occur,” she said. “The FLDS has too much to risk and too much to lose if they don’t abide by the laws of Texas.” In the end, the DFPS said that it had identified twelve girls, ranging from age twelve to fifteen, at the YFZ Ranch who had been victims of sexual abuse with the knowledge of their parents. Seven reached adulthood by the end of 2008, and three more have since reached adulthood. Two were twelve when they were married, three were thirteen, two were fourteen, and five were fifteen. Seven of those girls had one or more children. All were nonsuited with the exception of Merrianne Jessop, who was sent to live off the ranch with her new guardian, Naomi Carlisle.

If the plan all along has been to take aim at the problem of bigamy and underage marriage within the FLDS from a criminal angle instead of through civil proceedings, one can only imagine that the attorney general is holding his breath as the criminal trials get under way. (Perhaps he is also counting on additional convictions from an ongoing federal investigation regarding violations of the Mann Act and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.) Jeffs is one of the twelve men who will be tried in Texas, though his court date has not yet been scheduled. But even if the state convicts all twelve and puts them in prison, nothing can stop Jeffs from continuing to direct his members with total disregard for the law.

“This is just a lose-lose deal,” said a child psychiatrist who testified before the court. No clear pathway was without potentially devastating results. Charles Childress acknowledged that adoption was a traumatic option. But was it better, he asked, to return girls to families in which underage marriages had occurred and might occur again? “They think they’re going to wind up happily holding hands in heaven,” he said. “That doesn’t make it something we can tolerate in a decent society.”

But of course, to the parents on the Yearning for Zion Ranch, the more decent society is the one located behind their tall white gate. At the end of my visit last August, I stood outside the home of Bob Barlow and watched his well-behaved children wander out of the house and onto the lawn surrounded by a large flower bed. “I think folks are in shock that it’s still happening,” Barlow told me, when I asked about the upcoming trials. “When people see the truth, they’ll see we were vilified. I hope people judge us by what we are instead of emotions or a vendetta.”

Naomi Carlisle smiled as she told me that even though the group still has two years of trials ahead of them, she was more confident than ever that “heaven would prevail.” “It’s more than ‘We believe in Christ’; it’s that we want to be like Christ,” she said. “That’s what our life is.” Merrianne agreed. She goofed around with Willie Jessop for a minute, pretending to steal his truck, then, seeing that a small audience was forming on the porch of the house, she brushed the dirt off her dress and excused herself. She really needed to get back to the garden.