This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It’s New Year’s Eve, and George and Barbara Bush have their mouths set for Chinese food: You’ll read how, in this propitious moment, work and reward converge for a Taiwan-born Houston woman. Elsewhere, an innovative cop throws a switch and a terrorist is blasted on four sides by a Twisted Sister record, discovering to his horror that he’s the hostage. A black educator, a retired newspaper editor, a nun, a mechanic who specializes in fifties Chevys—there is nothing spectacular or glamorous about these occupations, only that they are at the heart of who we are. Those who go dutifully about the day, dealing with routine and respecting the common denominator, are the ultimate expressions of the Texas mystique.

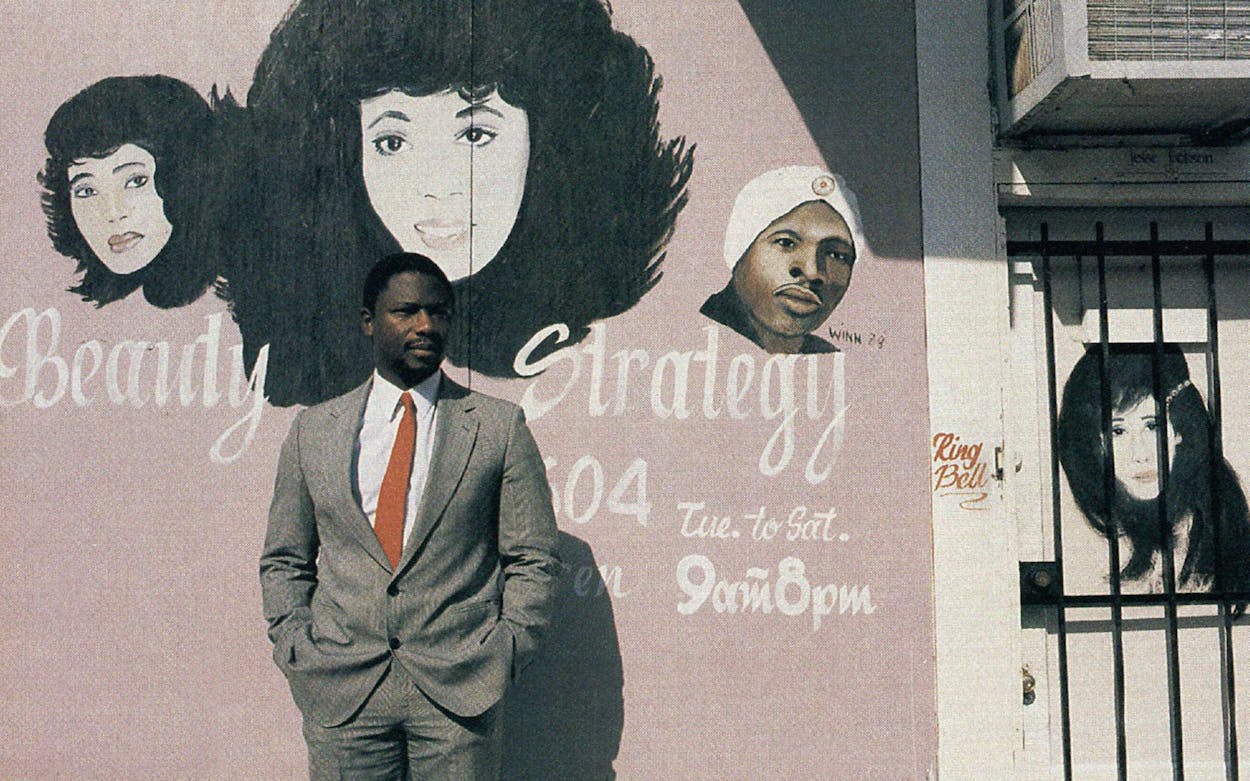

Terry Flowers

Educator

Dallas

Flowers, 31, is the principal of St. Philip’s School, a black school and community center in South Dallas. Though just west of Fair Park, St. Philip’s is in a part of Dallas that few outsiders see. Most of the children at St. Philip’s, which offers preschool through fourth grade, are on full or partial scholarships. By the time they go to public school, they are usually among the best and brightest in their classes. Flowers grew up in the ghetto of Chicago’s South Side, the eldest of five children raised by a strong-willed mother who supported the family on her $10,000 salary as a seamstress. The first in his family to obtain a college degree, Flowers went on to earn three master’s degrees in education. Personable and articulate, Flowers talks about coming to Texas in 1983 and his perception of black apathy in South Dallas.

So I had finished everything, all of the course work toward my dissertation to receive my doctorate from Columbia University. And my wife—she wasn’t my wife then, but we were about to be married—she had finished all her prerequisites to be admitted to the department of physical therapy at Texas Woman’s University, which was the number one program in the nation. We couldn’t pass up that opportunity. And in addition I had been working in the inner-city school program in Harlem, and I was becoming a little devastated, not seeing any growth in these kids. I just didn’t see where I was making any difference. So it was an opportunity to get away from New York and see another part of the country.

We didn’t stop in any small towns on our way to Texas. I’ve trained myself not to do that because I know what could happen if I stopped in the wrong town. We arrived in Denton in August 1983, and I started job hunting. I sensed that people were shocked to see a young black man walk into the personnel office of a public school and apply for more than just a teaching position or a maintenance-type position. I was more than qualified for an administrative position, but I sensed some tension. I don’t know if it was necessarily racial tension; it would probably exist anywhere that a young guy with three master’s degrees walked in. I ended up taking a job as a teacher’s aide in Denton. I had more credentials and more capabilities than the teacher of the course, but I needed the job to pay the rent.

I started interviewing at other places. I went to UT-Arlington and told them of my background and got that same look—who are you, trying to come in here and move into these kinds of positions? Finally, I saw an ad for St. Philip’s. They were looking for a principal. I had just been offered a job as director of the day care program at a Methodist church near Southern Methodist University. And even though the St. Philip’s job paid less, South Dallas was the type of neighborhood I wanted to work in. I just felt I could make more of an impact.

St. Philip’s is an island. You look across the street and you’ll see a liquor store. Next door is another liquor store, a convenience store, and some taverns. You’ll see an apartment complex where drugs are sold. So what St. Philip’s is doing is providing a vision of hope within the South Dallas community. People drive past here and say, “Oh wow! That looks nice, it’s clean, the grass is kept.” They see that South Dallas is not all depression and poverty and deterioration.

The difference in South Dallas and Chicago and Harlem is that although people were suffering and struggling in poverty in those other places, they had a sense of pride. I find that in South Dallas, outside the walls of St. Philip’s, there is a contentment with the state of things. People on the porch, rocking and waving as you go past but not doing anything, people playing dominoes five or eight hours a day, drinking, just hanging out on the corner.

In Harlem they were poor, they were addicted to drugs, but they were angry too, and they wanted to get out. In South Dallas people don’t seem upset about it.

Gigi Huang

Restaurant Manager

Houston

Huang (pronounced “Wong”) operates Hunan Restaurant on Post Oak, one of three restaurants owned by her father, James Huang. He was the bar manager of the Ambassador Hotel in Taiwan until 1968, when he was hired for a similar position by the St. Anthony Hotel in San Antonio. Shortly thereafter, he moved to the Lamar Hotel in Houston, where he became a favored host of Houston’s power brokers. When President and Mrs. Bush got a hankering for Chinese food for their private dinner last New Year’s Eve, Gigi and her father personally prepared the meals. A graduate of the University of Houston’s school of hotel management, Gigi, 25, is a serious, strikingly stylish young woman who is thoroughly Texan, right down to her twang.

I was named after the movie and also because my Chinese name sounded like Gigi. I was about four and a half when we migrated from Taiwan to Houston, and at that time I had two other younger sisters. Now I have four younger sisters, so two were born here in Houston. When we moved here, there were maybe three hundred Oriental families in the whole city, ya know. And today there’s like thirty thousand.

Both my father and mother wanted us to quote-unquote become Americanized to make sure that we could adapt better here in the United States. But now my father wants us to learn something about our culture. I can speak Mandarin Chinese, but I was never taught how to read or write it. The Mandarin language has like two thousand characters. You asked about Tiananmen Square, no, I can’t say that it affected me personally. I’ve never, ya know, been in China.

My life now is basically the restaurant. And it’s a healthy way too, because this is my choice. I’ve worked with my father since I was twelve. Right now I work six, sometimes seven, days a week, from ten-thirty in the morning until, ya know, around eleven-thirty or twelve at night. But it’s fun because we have a very personal relationship with our clients or guests. I tell my hostesses, “Your job is just like having a party at your house.” Business is my first priority, but I do keep a healthy balance, go out to movies and dinner with friends and go to a good party every once in a while. But no, I’ve never been married. Maybe, ya know, someday.

John Martinez

Garage Owner

San Antonio

John El Dorado Martinez’s garage on South Flores, called El Dorado Enterprises, specializes in restoring and repairing ’33, ’36, and ’37 Chevys. A hand-painted sign at the front entrance of the garage says, “If you don’t have any money, don’t waste our time.” Inside, hundreds of auto parts seem randomly arranged among stacks of tires. The walls are lined with hubcaps and hot rod club T-shirts—and a solitary color photograph of Pope John Paul II. In this milieu John Martinez, 37, flits about like a grasshopper in a toolbox.

My father had a little grocery store on South Flores not far from here, and he spoiled me. My first car was a 1931 Model A coupe. I was fourteen years old, and my father paid $750, which back then was a lot of money. You’re not going to believe this, but by the time I was 31, I had already had 31 cars.

What you see here are mostly parts for classic Chevy cars—a classic is a car that’s over twenty years old. We buy them and sell them and repair them. San Antonio has more classic Chevys than any other city in the U.S. People love them. In Turkey they still manufacture a ’55 Chevy body, the body only. It’ll have another engine, another interior, but the body is a ’55 Chevy. See that wiper motor over there, which was $11.95 in the fifties? Today it brings $143.45, and it’s rebuilt, not even a new one. A grill bar for a ’57 Chevy? $295! Back then it was about $15.95.

You won’t believe what a ’55, ’56, and ’57 are bringing today—$36,000, $48,000, whatever. And we’re talking about a car that only sold for $2,100 new. But try to understand, you get a new Camaro at $16,000 and what have you got, plastic and aluminum.

My favorite car of all is the ’56 Chevy convertible. I feel like the ’56 has a lovely body line. The ’55 is too square, the ’57 looks like the fins of a fish, but the ’56 has a perfect body, front and back. In 1957 Chevy came out with an awful lot of high-performance stuff—fuel-injection, four-speed transmission, positive traction. That’s why their ads read “hot and sassy.” I can show you records where in 1957 the Chevy in the quarter-mile outran Porsches, Jaguars, all kinds of high-performance cars at Daytona Beach.

I used to be a member of the Gear Grinders, but we had a falling out. They’re the oldest hot rod club in town. They meet the first and third Wednesday of every month at George’s Drive-In, 3316 Fredericksburg Road. Everyone brings his hot rod—any street machine is considered a hot rod when you’ve improved it by replacing your engine, your transmission, and your rear end.

You’ll see three hundred hot rods, everything you can think of. A ’31 Studebaker, ’32 Ford, ’40 Ford—people just love a 1940 Ford—a T-bucket, which is a Model T that is souped up.

A lot of horse-trading will go on at the drive-in. Someone will have a blower or some mags or tires they’d like to sell. You’d be surprised how many cars are bought and sold at the drive-in.

Jack Butler

Retired Editor

Fort Worth

Butler, 73, started at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram as a reporter in January 1943 and stayed for 39 years, advancing through the ranks to city editor, news editor, assistant managing editor, and finally editor (1962–73). After Capital Cities bought the paper, he was kicked upstairs “to the position of vice president in charge of being vice president.” A large, somewhat frail man —he’s had two heart-bypass operations—with snow-white hair and piercing blue eyes, Butler sits at a dining room table at his home in the city’s Meadowbrook section and looks back on his career.

I was in my mid-twenties when I came to the Star-Telegram. Those were the days of Amon Carter, Sr. He was Fort Worth, practically. He was our publisher, he was the chamber of commerce, he was the leading citizen; whatever he did went. I used to laugh, because the mayor and the city manager came up to his office to find out what they were supposed to do at city council. Sort of a benevolent despot, I guess. He built the Star-Telegram on the theory that if West Texas grew, Fort Worth would grow, and if Fort Worth grew, then the Star-Telegram would grow. It worked real well.

My God, how we covered West Texas! When I was news editor of the morning paper, I think we had 2,300 circulation in Hobbs, New Mexico. Hobbs was an oil town, and we had the best oil page in the state. We covered the people and the doings of West Texas. We weren’t that great on covering the doings of the world and probably not too good at covering the doings of the people in the United States. What we covered was our areas.

It’s true, the word “drought” would never appear in the Star-Telegram, not if it was connected with West Texas. Oklahoma had droughts; West Texas had prolonged dry spells. There was an old joke on the copy desk that one guy wrote a story after a tornado where they’d had a heavy rain, and the headline was BENEFICIAL TORNADO HITS WEST TEXAS.

You know who Charlie Guy was? He’s dead now, but he used to be the editor of the Lubbock paper for God knows how many years. Charlie and I were sitting in a hotel lobby at a convention, and I said, “Well, of course the Star-Telegram has never been a great paper, but I think it’s a good paper, and maybe someday we could make it into a great paper.” And he said, “Jack, what is a great paper? If it gives the people who subscribe to it what they want and need, I’m not sure the Star-Telegram wasn’t a great paper.”

In the fifties you didn’t read anything about black people in the Star-Telegram. Listen, they wouldn’t even run a picture of Joe Louis. You couldn’t get a picture of a black person in, except every Christmas we ran a picture of the black staff of the Fort Worth Club—that was Mr. Carter’s club—getting their Christmas bonuses. When I was assistant city editor, I got a picture and a story about a kid who was the first black Eagle Scout in Fort Worth. And I tried and tried and tried to get that in the paper, and it finally disappeared. I made up my mind that if I ever got to be the guy in charge . . .

When an editor makes a judgment about putting a story in the paper, he considers several criteria: Is it readable, is it important enough that it must be in the paper, is it true, is it libelous, is it tasteful? I think newspapers need to consider a few other things: How much harm is this going to do someone? One criterion ought to be responsibility. Another may even be compassion.

Now I didn’t always consider all these when I was an editor. One night the managing editor of the morning paper called me at home and said, “I have this story. A bunch of girls have come in here from Texas Woman’s University. And they have a lot of complaints and information about homosexuality in the dormitories. And I think we ought to run it. What do you think?” I told him, “If you’re sure it’s a valid story and these people are reliable and they’ll stand for being quoted, go ahead.” And so we ran it. What I didn’t know until the next morning was we had bannered it across the front page! In terms of importance, the story really didn’t make a tinker’s damn, but what it did was hurt a very fine institution. Three or four girls came in and bitched. Okay, people who had kids in the college had a right to know if there was some homosexuality in the dormitory. I suspect there’s homosexuality in most dormitories. We should have run the story, but banner it? No. By bannering it, we made it seem like TWU was a school populated by homosexuals.

I’ll give you a flip side of the news-judgment thing. A friend called me. His wife was an alcoholic. She had gotten drunk and hanged herself in jail. And he called and asked if I could keep it out of the paper. I said no, we couldn’t. You need to run stories of suicides. Somebody needs to know that when a person dies violently, there’s been a ruling that this person died by his or her own hand. It was devastating to my friend, but you have to add that to the criteria when you put a story in the paper.

When I came here, Fort Worth was a little town. A friendly place. Maybe not very interesting, but I enjoyed it. I sometimes miss the small-town atmosphere. They still call it Cowtown in the paper, but it’s not Cowtown at all.

Robert D. Cain

Police Lieutenant

Houston

Cain, 39, grew up in Alvin and attended Abilene Christian College on a football scholarship. With the Houston Police Department since 1973, he has worked his way from patrolman in the Fifth Ward to detective to coordinator of Houston’s world-famous hostage-negotiation team. One of his more innovative touches—and one being copied by police departments all over the world—is a specially designed van equipped with surveillance cameras, sophisticated sound and recording systems, and office space for the negotiation team. Personable and clean-cut, Cain is married and has four children.

When you’re from a small town like Alvin and go to a Bible college, the Fifth Ward is a kind of new experience. I remember this one situation when I was a rookie: a wife had cut her husband open with a knife, and he was sitting there in the chair with his intestines in his hands. He didn’t want to file charges, and she was mad and cussing and hollering at us. There wasn’t much we could do, which is what I learned to expect in domestic disputes.

I became a detective in ’79, homicide division, sex crimes unit. Adult cases, not children. What made it so difficult, it was such a personal type of crime. You had to talk to the victims, interview them, make them go through it again. I didn’t realize then how it was affecting me, but I became more paranoid. If my wife was five minutes late or if I called and she wasn’t home, I would think the worst.

I took over the hostage-negotiation team in ’82 and developed a training program and designed this thirty-foot motor home, which becomes our mobile command post during a hostage situation. That’s when we started getting into psychological warfare. Instead of just bullhorning and throwing in the gas and rushing the place, we developed a nonlethal approach.

First we gather intelligence and decide our strategy. We can take control of the suspect’s telephone line, make it where the only person he can communicate with is us. If he doesn’t have a phone, we provide him with one. I call it Star Trek negotiations because we’ve got cameras that can take you right into someone’s living room, supersensitive listening devices, a quad-speaker monitor system. Instead of using bullhorns, we surround the building with loudspeakers. We can blast him with messages or weird sound effects or music, anything from military marching music to gospel to hard rock, depending on whether we want to raise or lower the anxiety levels. There are probably two hundred different approaches we can use. We’re playing with the suspect’s mind, with his sense of security: He doesn’t know what to expect.

Sometimes we have nonverbal situations where we have to devise ways to communicate. We had a situation where a hostage talked to us by slamming her commode lid—once for yes, two for no. Another time a suspect who was robbing a fast-food place locked five hostages in the manager’s office. We were able to communicate through clicks from a partially broken phone and got enough intelligence where SWAT got on the roof, cut a hole, dropped down, and got all the hostages out without the suspect knowing. Then we went up to the door with an armored vehicle and said, “Guess what!”

I’ve been involved in 450 situations and we haven’t lost a hostage yet. I’m proud of that. And in fifteen years on the force I’ve never had to pull the trigger of my weapon, though I’ve come close several times. If I ever have to pull the trigger, I know I can. It’s a matter of survival.

Sister Maria Carolina Flores

Nun

San Antonio

Flores, 49, teaches at Our Lady of the Lake University. The daughter of a semi-skilled laborer and a housekeeper in Fort Stockton, she lives a few blocks from campus in a small, church-owned house in a West Side neighborhood with burglar bars on the house windows and piñatas for sale in the yards. Flores has short gray-streaked hair and Aztec features, and she wears a blue-jean skirt, red blouse, and silver earrings, reinforcing her irreverent approach to church dogma.

In Fort Stockton the railroad track divides the city, and the Mexican Americans lived on one side and the Anglo Americans lived on the other. We had segregated schools until I got to the seventh or eighth grade. So I grew up in the Mexican American Catholic environment. I was in high school before I knew that Anglo Americans were Catholic too. For me, Catholicism and being Mexican were the same thing. How could an Anglo American be Catholic?

There were unstated rules about behavior, where you go and where you don’t go. The city swimming pool was off-limits for Mexicans, et cetera. By the time I got to college, things obviously had improved. But the attitudes were still there, the looking down your nose at people. The dorm mother always complaining, accusing people, being suspicious. Something was missing, maybe it was one of us—that kind of shit. So I thought, “I’ve had enough. I’m eighteen, nineteen years old, and I don’t have to put up with that anymore.” So I left, and I came to Our Lady of the Lake. And why did I come here? I really don’t know.

I was just looking for a place to go.

Did I always know I wanted to be a nun? No, I didn’t. I did not grow up being very Catholic, because we were out in the boonies, and the church did not have a great deal of resources and activities for the little town. There was one priest. He got there a year or two before I was born and stayed for fifty years. There was not a great deal of Catholic culture, so to speak. It was very much a frontier Catholic—the very basics and nothing else. There weren’t any nuns there when I was growing up. An aunt of my mother’s did the work that nuns do now. She taught children their prayers and got us ready for First Communion.

I came here and went to school, and almost all the teachers were nuns. I guess it was probably towards my senior year when a friend who had graduated a year ahead of me joined. That’s when I got the idea that maybe I ought to think about it. And I don’t know if I make decisions like this all the time—I hope I don’t—but I never sat down and calculated and reached a conclusion.

Yes, I think women should be ordained. They’re just as qualified as the next and we haven’t yet seen a sound theological argument for not, except the fact that we don’t because we haven’t. But I wouldn’t be interested in being ordained. I don’t want that job!

- More About:

- TM Classics