One night in the spring of 2007, when I was thirteen, my little brother and I cupped our hands to our upstairs hallway window, looked through the cigar smoke in our backyard, and tried to find Steve Miller. There was a grown-up party swirling around outside, but we couldn’t figure out which adult was the celebrity guest. We’d learned every Steve Miller Band classic rock hit from 93.3 The Bone, but we had no idea what the guy looked like. The albums we owned either had a painting of Pegasus or a man in a Joker mask on the cover, and every male standing in our backyard looked like he worked in real estate development.

Steve Miller had attended the Dallas all-boys school St. Mark’s fifty years before we did, and he was back to play its hundredth birthday concert. Our house was near campus, and St. Mark’s borrowed our yard for his welcome dinner. We were bummed we couldn’t spot the famous guy mingling with everyone else, but after a few hours of gawking, my brother and I were allowed to come down and say good-night. We walked outside, and our parents tilted their heads toward the blazered man who could sign our CD copy of Greatest Hits 1974–78.

He was the one who looked the most at home with a cigar. Even though he was sixty-something years old, his hair was longer, featherier, more swooped and tangled than the dad cuts at the party. We walked up, and he blew out smoke and grinned. “When I was your age,” he told us, “I was already a working musician! I wrote out professional contracts, and I paid my brother to drive us to gigs at frat parties.” Not to be one-upped, I told him my band had recorded four songs and was a fixture on the bar mitzvah circuit. His grin widened, and he asked if I had two guitars I could bring outside.

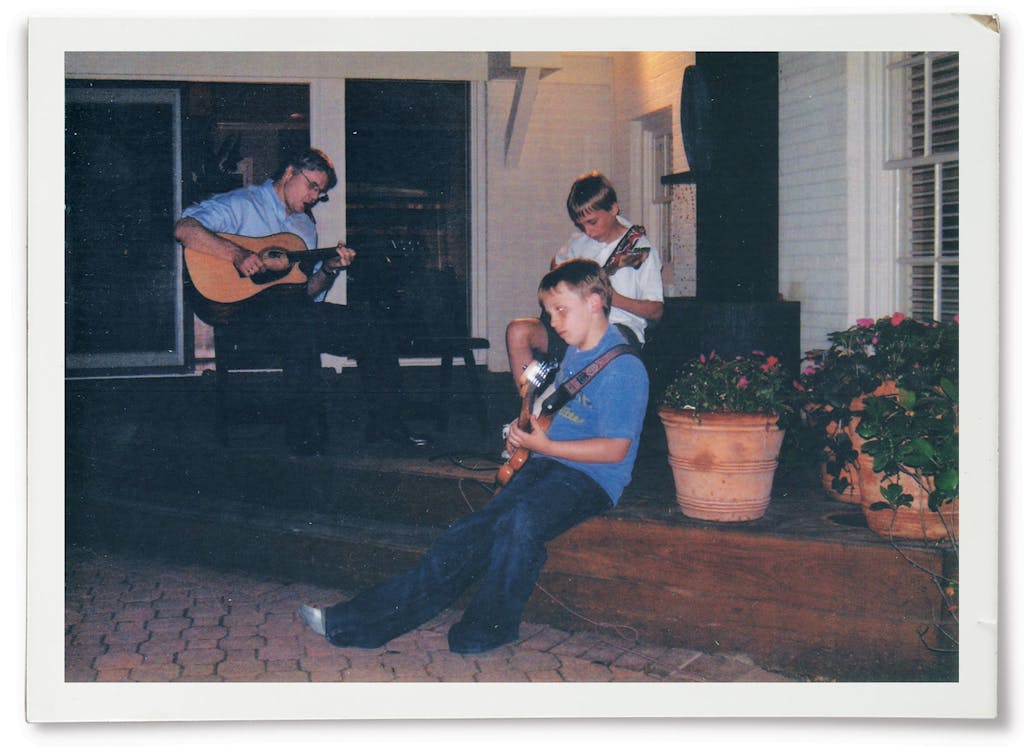

I did, and my brother brought his bass. Mr. Steve—he said he wasn’t comfortable with “Mr. Miller”—left the donors’ table to play music on the porch with two middle schoolers. My brother sat down and thumped out a rhythm. Mr. Steve laid down some chords, and I tried to show off. I played some blues licks, the only kind of guitar licks I sort of knew how to play. I ran up the pentatonic scale like my uncle had taught me, hammered a Freddie King riff, and watched Mr. Steve’s eyes light up a bit.

I didn’t realize it then, but I was crudely speaking the same vocabulary that he’d used to build his career. Before he rejoined the adults, he showed me a chord progression the great Texas blues musician T-Bone Walker had taught him when Mr. Steve was my age, and then my parents made me go to bed.

But before I left, he extended an invitation: He was headlining the school centennial concert, which was being held on our football field the next day, and he asked if I wanted to watch the sound check. Yes, I said, I did.

The following afternoon, from the side of the stage, I watched Mr. Steve twist knobs on his amp for twelve minutes. He said he was chasing a perfect high-end tone. He walked up to the mic and kicked off “Fly Like an Eagle.” Halfway through the song, he spoke into the P.A., “Mr. Max, come up and play a solo.” He handed me his guitar. Between the band members, my family, the sound technicians, the groundskeeping crew, and assorted onlookers, there were maybe a few dozen people there—my third or fourth biggest crowd ever. I tried to imagine I was still on the porch, and I played the same licks as I had the night before. The song ended, and Mr. Steve asked if I wanted to sit in with his band that night at the concert.

I was bummed, because I had to decline. I was going to be a groomsman at my childhood nanny’s wedding that night, and it started at six. I told Mr. Steve thank you and asked if maybe we could play together at St. Mark’s 125th birthday. He said sure—but if I arranged things right, maybe I’d be able to make the 100th, too.

Thanks to my mom’s willingness to drive her Toyota Highlander at illegal speeds, I did. That evening, after the wedding ceremony, I walked a bridesmaid out of the chapel, changed out of my tuxedo in the car, and made it onstage while Steve and a band of St. Mark’s high schoolers began “Fly Like an Eagle.” I didn’t have a guitar, so I stood behind them and looked out at the hundreds of people gathered in the audience. After the second verse, Mr. Steve unstrapped his Fender Stratocaster and handed it to me. Take a solo! Biting the left side of my tongue, I stared at my tennis shoes and played the same licks I’d played the previous night in my backyard, and at sound check earlier that day. I gave him back the guitar about two minutes after he had lent it to me. The song ended, and I walked offstage and made it back to the wedding reception in time for cake.

Driving around Dallas–Fort Worth in the early aughts, it was hard to miss hearing the Steve Miller Band’s seventies hits. Stuck on the LBJ Freeway or gunning down the tollway, my parents would flip between 92.5 KZPS and 93.3 The Bone, DFW’s nearly identical classic rock stations. Each station played a narrow rotation of songs that rarely reached past the early eighties, soon after people started burning disco records. Before I was out of a car seat, I knew that Lynyrd Skynyrd wasn’t bothered by Watergate, what portion of the night AC/DC got shook, and what Steve Miller had to say about the “pompatus of love.”

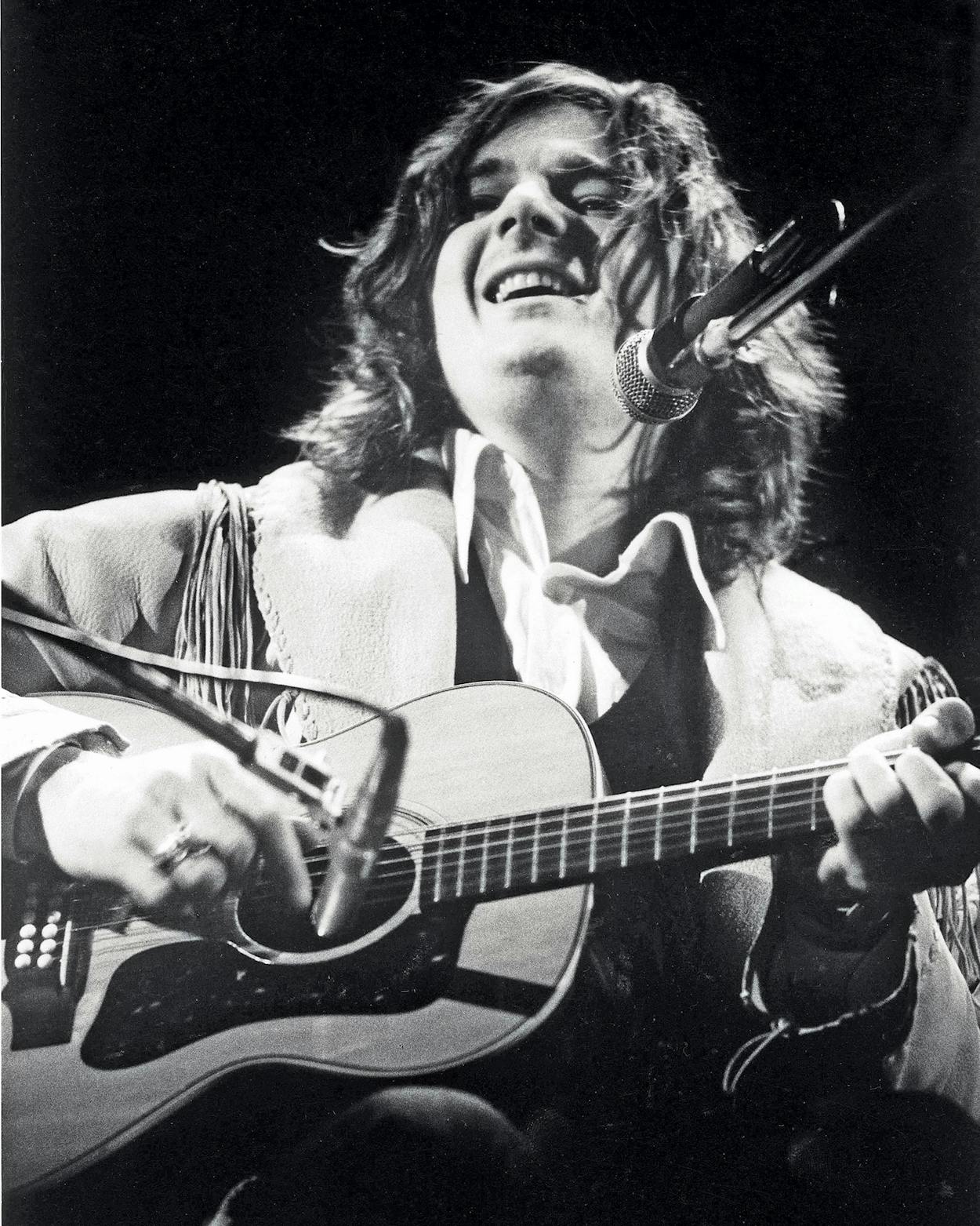

I remember multiple childhood car rides during which we’d toggle stations and discover that 92.5 and 93.3 were playing the same Steve Miller track at the same time. Songs like “Fly Like an Eagle,” “Take the Money and Run,” “The Joker,” “Rock’n Me,” and four or five others felt like they were always there, riding some permanent radio wave. I didn’t mind. I grew to dig the sweet pastoral harmonies, the laid-back grooves, the trillion-dollar hooks. With militant ambition and a light touch, Miller wove psych rock, Texas blues, country music, and other threads into escapist, inescapable pop.

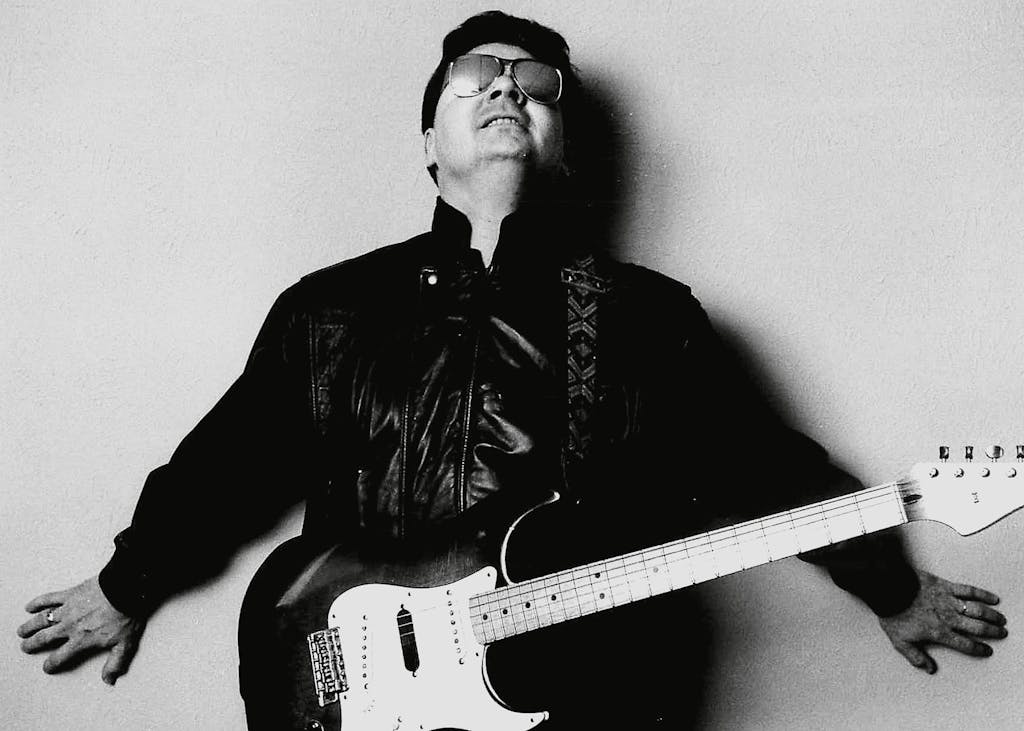

But though I’d heard so much of Steve Miller’s music, I didn’t know anything about Miller himself. His songs dance around any sense of biography: “The Joker,” after all, is a fictional list of alter egos—and “Steve Miller” the man is as elusive as his singles are ubiquitous. I don’t think I ever saw his face on TV or in magazines. (I wasn’t alone: one time, I was told, a security guard in Las Vegas wouldn’t let Steve onto his own stage without seeing a pass.) His name doesn’t come up in too many conversations either; many people never realize that all these songs belong to one guy.

Growing up, I didn’t know any of the music Steve Miller made before or after his hit parade. He released his first album fifty years ago and his most recent one in 2011, but KZPS and The Bone mostly played songs from 1974 to 1978. As a result, I didn’t know that Mr. Steve had recorded a 1967 live LP with Chuck Berry. I hadn’t learned that Les Paul—the jazz-and-standards legend and co-inventor of the solid-body electric guitar—was his godfather and mentor. (Steve’s father, a doctor and recording equipment enthusiast, was the best man at Paul’s wedding—which was held in the Miller home—and Paul and his bride, Mary Ford, spent their honeymoon in Steve’s parents’ bedroom.) I had no idea that when Steve was about nine years old, T-Bone Walker—a guest at his parents’ house—taught him to play guitar behind his back. Or that he had been a major figure in the sixties San Francisco psych rock boom. Or that he had opened a few of Janis Joplin’s and Jimi Hendrix’s last shows. I didn’t know that he had the foresight to control his own publishing when that was an unusual thing to do; I didn’t know what publishing was. I didn’t understand what it took to do all of that stuff, and I didn’t know why he wanted to show me how to do any of it, either.

After the St. Mark’s concert, I didn’t hear from Steve for about a year—but then again, I didn’t really expect to; why would anyone who has sold tens of millions of albums remember to email a fourteen-year-old bar mitzvah guitarist? But in early 2008, his manager sent me an invitation to his summer concert at Fair Park, so at the end of May, I carpooled with some family friends to South Dallas. Before the show, Steve Miller’s friends, colleagues, hangers-on, and family circled backstage. I stood in the corner, unsure if Mr. Steve would recognize Pubescent Max. Then, as he headed for the stage, he walked up to me: “Mr. Max, looking tall. I gotta run, but why don’t you come say hey after the gig?” I was surprised he remembered me, but I also felt a little mopey; I’d wagered a piece of my self-worth on a chance to play onstage again.

I watched the show from the crowd, and after it was over, my “chaperones” for the night, St. Mark’s assistant headmaster David Dini and his wife, Nancy, and I walked to the back lot to thank him for our tickets. We went inside his tour bus, and after a short conversation, he said he had to leave for Houston. I stood up to go, and he stopped me. “Where are you going?” he asked. “I thought you were coming too.”

I looked to Mr. Dini for an indication that leaving town was kosher. He called my parents to check, then gave a thumbs-up, and the bus started moving. Soon Steve, the Dinis, and I were stepping out onto a Love Field runway I had never seen before and then onto a private jet. A few minutes later, we were in the air, and Steve was explaining the mathematics of private jet travel. The transit time he saved allowed him to add gigs each summer, and those extra shows paid for the flights a few times over. We touched down 45 minutes later at a Hobby airport private terminal named—with classic Houston subtlety—Million Air, but I couldn’t argue with Mr. Steve’s arithmetic.

We spent the night at a hotel downtown, and the next day we drove out to the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Pavilion, an ampitheater in the Houston suburbs. During sound check, Steve had me take a few solos. I had spent the last twelve months with the pentatonic scale, and I was starting to play with feeling. I was learning how to bend a string that much, leave a hole here, shake a note like this, and now I was hearing all of it echo off thousands of empty seats. After my speed-picking flurry, though, Mr. Steve walked to the edge of the stage and told a better story in ten notes.

Sound check ended, and I went to the bus with Mr. Steve and Mr. and Mrs. Dini to hang for a few hours before the show began. The four of us started talking about St. Mark’s. The secret reason I got to tour with Steve Miller: my old school is a bit of a cult. It’s not that uncommon for alums to engrave the school crest on their cowboy boots and put St. Mark’s in their will. To be clear, Steve didn’t graduate from St. Mark’s; right before his senior year, he got expelled, he says, for having a bad attitude and for running an underground newspaper. (He eventually graduated from Woodrow Wilson.) He more or less excommunicated himself for five decades, until Mr. Dini reached out. Steve Miller forgave St. Mark’s, Mr. Dini became one of his closest friends, bygones were allowed to be bygones, and Steve’s born-again school love brought him to our centennial concert.

Steve asked me about my life as a Marksman, and we talked about the band he had formed during his time there that included his classmate Boz Scaggs, who went on to have his own notable musical career. As his stories pivoted to handwriting exams and fistfights with bullies, the coach started filling up with guests. Apparently, if you’re famous, it’s not that hard to meet other famous people. Your agent calls someone else’s agent, and a tour bus meeting is arranged. A revolving door of weird surprises came through: Glenn Close, two Dixie Chicks, Luke Wilson (another St. Mark’s alum), the Paul Mitchell hair care guy with the billion-dollar hair, and Tim McGraw.

Most of the visitors shook Steve’s hand and left, but McGraw came to stay. The modern Nashville sound owes more to “The Joker” than it does to “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” and McGraw is a big fan of the Steve Miller Band. Tim took off his hat, and Steve put a hand on his shoulder. “Tim, meet Mr. Max. You’ll be onstage tonight, one after the other.” Tim McGraw and his jawline sat next to me and my unchanged voice and told me that touring with his wife was keeping him “out of trouble.” I didn’t know what he meant by “trouble,” but I understood him when he said he was nervous about the gig.

As showtime neared, Mr. and Mrs. Dini and I took our places in the audience, near the sound mixer. It was my second Steve Miller Band show in two nights, and I was getting a feel for the scene. Standing on the concrete or sitting in the grass, we were seven thousand white people eating hot dogs and waiting for the concert to start. A lot of the crowd looked to have come of age during the Greatest Hits 1974–78 era: frat-brothers-forever and good ol’ boys, ex–party girls and women who probably pulled down six figures at their corporate jobs Monday through Friday, all excited to dive back into tape-deck memories and beer. There were also older hippies, solemn guitar geeks, and lots of kids who grew up on classic rock radio and were, like me, running on borrowed nostalgia.

All at once, the crowd lights faded, a Jetsons synth panned across the speakers, and the band walked onstage. They always start with a hit, and tonight it was “Jungle Love.” The fans set down their hot dogs and started to dance, and I remembered something Steve had said on the plane. To a lot of Steve Miller Band fans, the seventies hits are like “chocolate cake.” They’re warm and pleasurable comfort food, reminiscent of a Summer of ’76 picnic. They’re rock without the chaos, the blues without the pain, an America with the freedom of an endless road trip. And although Steve laid down roots in Chicago blues clubs, went out on a limb in the San Francisco psychedelic rock explosion, and has even played jazz at Lincoln Center, the ticketholders mostly want that classic rock.

The Steve Miller Band visits forty to fifty cities each tour, and they play roughly twenty songs a show. (Their 2018 tour, which will celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Steve’s first album, hits San Antonio, Allen, Sugar Land, and Austin in late July.) Since at least the nineties, the band hasn’t been able to leave town without playing “Take the Money and Run,” “The Joker,” “Fly Like an Eagle,” “Jet Airliner,” “Swingtown,” “Rock’n Me,” “Abracadabra,” “Jungle Love,” and a few other greatest hits. In the remaining slots, they squeeze in obscurities from new albums, or jazz standards featuring Steve’s cigar-

smoke legato voice, or Texas blues songs that let him wail on the guitar. The problem is, when Steve announces a song that’s not chocolate cake, hundreds of people get up for a hot dog. So, halfway through that set in Houston, he didn’t say, “We’re going to take a break from radio hits and play four blues covers”; he just asked the crowd to help welcome to the stage a fourteen-year-old kid from the great state of Texas.

I walked out, plugged into a Dr. Z amp, and helped kick off “Mercury Blues,” a song first recorded by the K. C. Douglas Trio in 1948. Things immediately felt different than they had at sound check. A few hours earlier, I had been standing under daylight, with my guitar echoing off empty seats. Now the stage was a fish tank. The spotlights beat down on me, and I couldn’t see beyond the first couple of rows. I turned to the band for some signals, but on a stage that can fit a symphony orchestra, the seven guys dressed in black disappeared behind a row of towering purple stage columns. Any sound roaring from the main speakers got absorbed by thousands of bodies, and the stage was so quiet I could hear my pick clacking the strings.

I chugged rhythm chords for a few verses, until Steve tilted his head to say, Take a solo! Then I kind of blacked out. I wish I could say that I tuned in and traveled to some astral plane, but the truth is, I just fell into muscle memory to avoid falling apart. I’m pretty sure I improvised with the same licks I had used in the sound check, although that’s just an educated guess. I blacked in three songs later, soaked, and walked off the stage to find Tim McGraw smoking a cigarette and mouthing the lyrics to “Rock’n Me.”

Sitting behind an amp at the side of the stage, I watched Tim join Steve onstage. I was still wheezing from the heat and nerves, but they looked sweatless. In a black shirt and tinted glasses, Steve tapped his boot and kicked off the first verse of “Rock’n Me.” His voice filled the amphitheater like barbecue smoke. I closed my eyes; his singing was as weightless as it had been on the 1976 recording of the song. Tim came in on the next verse, and Steve counterpointed on guitar. Almost motionless, his hand unfurled these ringing bends and melodies. After that display of effortlessness, the call-and-response with the audience felt a little forced. Keep on a’rock’n me, baby. “Now you sing it!” Keep on a’rock’n me, baby. “Now we’ll sing it!” Keep on a’rock’n me, baby. He had done the same thing the night before, in Dallas. I’ll admit, though, that from backstage, thousands of fans “singing it” sounded pretty thunderous.

Once the band and the crowd were done rock’n each other, I decided to rejoin the audience. Mr. and Mrs. Dini and I walked downstairs and into a cohort of highly enthusiastic older female fans, one of whom gave me an impromptu backrub. Another asked me in a gravelly baritone to sign a ticket stub “for her daughter,” and Mr. Dini decided it was time for the bus. On our way out, middle-aged men apparently impressed by my brief time in the spotlight lifted their Styrofoam cups in our direction.

After the show, at our hotel, Steve opened his Tupperware box of Cuban cigars and told me that I should never reenter an audience after playing on a stage. In his words, one reason he’s tried to remain low profile for decades is that, once you’ve been touched by the spotlight, boundaries between you and strangers get destroyed in a pretty frightening way. I nodded and bit into the Steve Miller Band–themed confection that the hotel’s pastry chef had sent up—a frilly, blue icing Pegasus on a white layer cake.

Steve bit into a cigar. He told us about standing on I-35 in Austin in the mid-sixties, after he’d decided to bail on the University of Texas, and flipping a coin to decide whether to drive to New York (heads) or San Francisco (tails). It came up tails, and he joined Jefferson Airplane onstage the next week at the Fillmore West. He talked about playing 120 gigs at the storied venue and recording with Paul McCartney as the Beatles dissolved (McCartney is credited as “Paul Ramon” on a track off the Steve Miller Band’s third album). And then he tired of reminiscing and got up to turn on Team America: World Police. Steve can quote the whole thing, but I was up past my bedtime, watching a movie I wasn’t allowed to watch yet, and I fell asleep in my chair.

Related Story

Playlist: Steve Miller Influencers, Hits, Semi-Oddities, & Admirers

The rock star’s most essential music, from his earliest influences through his biggest hits to the artists he’s influenced himself. Read story.

For the next few years, nearly every time the Steve Miller Band came to Texas, I’d sit in with them. We’d usually start in Dallas and fly to Austin or Houston, and I slowly got better at playing simple blues guitar licks. Soon Steve’s mentorship expanded offstage.

For years, Steve spent roughly a third of the year on the road, a few months living on and sailing around the San Juan Islands in Washington, and the rest of the year near the ski village of Sun Valley, Idaho. I first visited his Idaho compound during ninth grade Christmas break, when, after a year of email correspondence, the Millers invited Mr. and Mrs. Dini and me to bring our families to visit.

Steve met us at the gate on skis. He had just finished guitar overdubs and a workout. He showed us around the property, which is surrounded by mountains. A river runs behind the main house and a skate-skiing track laps around pine clearings. Spread out along walking paths are three guest cabins, an art workshop, a storage space, a multistory recording studio, and the main house, which Steve designed.

We ate dinner in the house under a wood ceiling that vaulted over cigar musk and piles of books. I sat next to Andy Johns, the British producer, who drank a case of beer before dinner and told my fifteen-year-old self about mixing Exile on Main Street on heroin. Steve and his wife fried ribeyes and threw them to their three rescue herding dogs and then sat down to play Go Fish with the half-dozen Marshall and Dini kids.

Go Fish got shockingly competitive, but I could think only about the songwriting demos zipped inside my ski jacket’s left pocket. Before I’d met Steve, I’d been writing songs, maybe four or five a year. But observing his audiences made me want to write more. During many shows, I’d see a fan enter the hot dog line while the band played a blues cover he didn’t know, just to turn around and sprint back, sans dog, when he heard the intro to “Abracadabra.” On the bus after a show in Oklahoma the previous summer, I mentioned this trend to Steve, and he said that most fans don’t listen for virtuosic guitar phrasing or vocal legato; before everything else, they’re there for the songs. When I got home, I tried to write two or three songs every month.

But I didn’t know when to give the demo CD to Steve. He was officially on vacation, but he was mixing his album, and he was painting in his art barn, and he was doing yoga, and he was fielding his own publishing calls, and he was meditating, and he was founding a record label, and he was designing an island compound, and he was playing Go Fish. At 1 a.m., though, after watching Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, we sat down in the kitchen to talk. I prefaced by telling him that these songs hadn’t come out as well as I’d hoped, and he cut me off. “Never tell anyone what you make isn’t good,” he said. “Let them listen and decide.” He put on his headphones and queued up the songs. I watched him enter the same state of focus he willed during sound checks, and I saw his eyes light up. The four songs ended around 1:15, and he suggested we go skate-skiing.

We sat outside on the porch and started buckling our skis. “There are a lot of ideas, sounds, moods, and feelings in those demos,” Steve said. “You’ve got a strong point of view and a feel for storytelling and a sense for melody. As songwriting, these are very, very good.” He clicked in his second ski and hopped off the porch. I rushed to get my boots on. In my mind, this was it: you go moonlight skiing with a rock star, he turns a spotlight on your songs, and you’ve made it.

Skate-skiing, apparently, is the bastard child of cross-country skiing and ice-skating. You’re supposed to pivot your feet into a V shape, kick off the inside edge of the ski, and swing your arms for power. Steve contorted like a swan and glided away. I got my blades on, trudged through powder for fifteen yards, and stopped. I leaned on my poles like a wet tarp. After my eyes adjusted, I saw him waiting at the top of a tiny molehill. I tumbled up the incline, aching but certain that I was about to receive some kind of hilltop “A star is born” initiation ceremony.

“Your CD is promising, Max. Especially for a fifteen-year-old.” Steve fixed both poles in the ice. “But in music, you have to hit a real home run. And then two more home runs, and then a triple immediately afterward. And then maybe you own the world for a while, but then you either have to write something even greater, or you disappear, and that’s how it really works.” If I wanted to “climb the mountain,” he told me I’d need a routine. I’d need to master my songwriting voice: writing every day, charting other songs’ chord progressions, feeling out the rhythms of words and the arcs of melodies. I’d need to tighten up my guitar voice: practicing scales every day, exploring tone in my fingers and through an amp. I’d need to find my singing voice: practicing scales, studying harmony, controlling my breath, learning to shape tones in my throat and phrase them through a line. I’d also need to find the right musicians, practice until we were a single organism, and figure out how to bring a song to life in a crappy venue with a bad P.A. Of course, we’d also need to develop an aesthetic and learn how to produce. Then, if we pulled all that off, we’d need to set up a publishing company and sign a contract that preserved our blood in an industry famous for leeches. After that, I’d really have to get to work.

By now it was 3 a.m. The molehill was cold, and I was out of energy, so I told Steve I was going to skate-ski to the guesthouse. He glided off, and once I was out of his sight, I took off my blades and walked along the skate-skiing track to bed.

A decade or so after that night, people ask me, “Are you still doing music?” I say yes, and in a way, it’s the truth; I still play guitar and write songs. But in the way that they mean—performing onstage and trying to make it—the honest answer has faded to no.

At one point, it looked like things might turn out differently. In 2008, when I was in New York City for summer vacation before my freshman year of high school, Steve invited me to play with him and Les Paul. It was a minor show, a Monday gig at a Times Square jazz club, but I got stage fright knocking on Paul’s greenroom door. Inside was my mentor’s own mentor, the guy who taught Steve his first chords. I walked in, and 93-year-old Les Paul looked up from the sofa. “What kind of music do you play, kid?” I wobbled out an answer, and his eyes got small. “The blues? Kid, anybody can play the fucking blues!” When we got on stage, Les grinned, Steve grinned, and I coated my Gibson Les Paul with sweat. They played thirteenth chords and weird textures and led me away from the blues. After the show, some guy from the crowd asked me to sign his guitar. As I told the Dallas Morning News two years later, when they wrote an article about my friendship with Steve, “In some ways, I’m getting the same treatment from Steve that he got from Les. It’s a cool opportunity.”

But I eventually botched my cool opportunity. I spent a good chunk of high school flying to Sun Valley to record my songs, but by the time I showed up in New York for college orientation, in 2012, I barely mentioned to people that I played guitar. Fear and laziness had killed my music routine, and I hadn’t talked to Steve in a year. He was grieving the deaths of some close friends (including Les, who died a year after I’d met him), and I was trying to be a normal freshman. Being Steve’s mentee had put me under the spotlight and in his shadow, two places where I wasn’t confident enough to stand.

No longer a naive fourteen-year-old, I couldn’t black out and play under stage lights without thinking. Becoming aware of how I looked and sounded robbed me of my blind confidence. By the time Wikipedia listed me as a member of the Steve Miller Band (an error that was eventually corrected), I knew I was being defined in terms I’d fail by. I wasn’t a member of his band, and I was never going to make it like he did. On some level, I wouldn’t make it like he did because musicians my age had come along too late to surf classic rock’s never-ending radio wave. Mostly, though, I wouldn’t make it like he did because I didn’t have it like he did.

When I started playing music, I thought the it in having it was some glowing X factor that famous musicians receive at birth. And when talent and undeserved privilege dropped me onto a big stage at a young age, I thought I had it. Then I looked under the hood of a successful music career. Five decades after Steve Miller released his first LP, he still practices singing on his bus, extends sound checks to the point of exhaustion, and pulls all-nighters to overdub thirty-second guitar parts. Steve’s mentorship taught me something that I didn’t want to learn: it isn’t a quality that you’re given but a question of how much you’re willing to give. Whether you want to make high art or big-money chocolate cake, you have to be monomaniacally committed to getting there. You won’t create music that’s effortless or individual without giving your effort or yourself completely to it. And by that definition, Steve has it, and I clearly never did.

My music dreams died a tiny bit each day I didn’t work to bring them to life. I assumed Steve’s reasons for giving me his time had died, too. One afternoon in 2012, though, as I was sitting in my dorm room, I looked down from my copy of the Iliad and saw a call from “Steve M” on my iPhone. I picked up, and he said he was in New York having dinner with friends in Midtown. I put down Homer and told him I’d be there.

Before we ordered, Steve asked the question I was afraid of. “Max, how’s your music coming?” I gave a more or less honest answer and waited for the grimace. Instead, he smiled and said, “Well, then, tell me about the philosophy you’ve been reading.” We talked Marx and quoted Arrested Development, and he wanted to hear about my brother’s high school debate career. Later in the meal, Steve took a bite of his porterhouse for two, drank from his glass of nonalcoholic cabernet, and announced his new architecture project. He was refurbishing a turn-of-the-century brownstone on the Upper West Side, and he was moving to New York.

In the summer of 2016, right after my college graduation, the Millers invited my family to dinner at their refurbished brownstone. At the time, Steve was in the public eye in a way that he hadn’t been in decades. Months before, as he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he called out the organization for its mistreatment of inductees and exclusion of female artists. (The New York Times wrote, “Steve Miller—of all people—brought some punk spirit to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Friday.”) We basked in the afterglow of his truth-to-power moment while he made everyone sandwiches.

We sat at the kitchen table, and he asked about an article I’d just written in my university newspaper. Throughout my college years, he encouraged all my pursuits with the same language he used for music. Whether I was writing amateur philosophy or co-hosting an internet radio show with three regular listeners, he told me to “Embrace it completely; onward and upward.” I was slow to learn it, but Steve taught me the lesson I’m most grateful for: find something good—music, writing, skate-skiing, friendship, mentorship, Go Fish—and give yourself entirely to it.

In his music room after dinner, he asked if I wanted to try his new guitar. He handed me a travel-sized instrument that was honey-blond and practically glowing. I struck the low E, and the hollow body made a crystal rumble. He grinned and opened a case leaning against an amp. Inside was a guitar that looked exactly like the one in my hand. “I had them make one for each of us,” he said.

On the sofa, he started playing those T-Bone Walker chords he had shown me that first night we met, when I was thirteen. He nodded for me to take a solo. I played the licks I’ve always played. This time, I slipped on a note and banged my new guitar into a lamp. He laughed and kept strumming. I started up again, trying a style I could no longer perform, on a gift I didn’t deserve, from someone who gave it anyway. I ran up and down the blues scale, which of course made me think of Les Paul. Steve had told me years earlier that Paul’s death almost broke him. Since then, others he had worked with—Norton Buffalo, John King, James Cook, Lonnie Turner, Andy Johns, B. B. King, Joe Cocker, Glenn Frey, Chuck Berry, Gregg Allman, Tom Petty—have made the same exit.

Steve Miller faces more loss every year, performs the same greatest hits every night, and still gives himself completely to the next thing. I finished my solo, and he started to play lead. I closed my eyes; he had gotten better since that night on my porch. A decade into our friendship and 74 years into his life, Steve Miller is still showing me how to keep growing up.

Max Marshall is a writer based in Brooklyn and Dallas. He recently completed a Princeton in Asia journalism fellowship in Hanoi, Vietnam.