Being a movie star hasn’t been what I thought it would be. I had this idea that I’d make lots of money, that my presence would overwhelm people, and that my sex life would somehow be like what they talked about in the National Enquirer. You know: “I Want Gunnar’s Baby,” Young Starlet Sobs. That sort of thing. I guess I was just naive. The truth is that I have made very little money, most people don’t even recognize me, and those who do certainly don’t think about sex.

Maybe the problem is with the movie I was in. It was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and I was Leatherface, the brutish, moronic killer who managed to dispatch four people in the eighty-some-odd minutes it took to get through the bloody thing.

Actually, now that I look back, I don’t mind that it didn’t work out the way I had thought it would. Nothing in the movie worked out the way we expected.

To begin with, I got the part for an unusual reason. I had answered the cast call and eventually had an interview with Tobe Hooper, the director. After explaining the part, he asked if I was violent. I said no. He then asked if I was crazy. I said no, He looked a little concerned and asked if I could handle the part. I said, “Sure, it’s easy.”

He sighed with relief. “Good. You’ve got it. I knew you were right when you walked in and filled the door. We’ll put high heels on you and make you look a little bigger.” So much for my acting ability.

So right away I figured that it wasn’t exactly a talent-intensive affair. And I never thought it would succeed the way it did. I expected it to make a few hundred thousand dollars, enough to pay back the investors. And I expected that after everything settled down, a few hard-core horror freaks would remember it.

At most I figured the high point for me would be the premiere at a South Austin theater one October night in 1974. The manager was nice enough to let me in free, because I convinced him that I really had been in the movie. There for the first time I saw this grisly thing we had created. I saw myself on the screen, running around with that machine. I saw how all of us looked, this grotesque family that killed people, cut them up with a chain saw, and sold them as sausage. I thought it was wonderful. My date walked out in the middle of it. Afterward a few friends gathered in the parking lot behind the theater, where they signed the Gunnar Hansen Fan Club charter in red ink and then gave me a defunct chain saw. We had a great time that night. And we thought that was that.

But right away things changed. Almost immediately the movie started to get attention. Rex Reed loved it. Johnny Carson began to make chain saw jokes. Newspapers across the country wrote about audiences being repulsed by the explicit violence. People complained, saying it should be rated X because of its violence. (The criticism climaxed two years later with a story in Harper’s titled “Fashions in Pornography,” in which the writer called me an “obese gibbering” castrato and condemned the movie as “a vile little piece of sick crap . . . with literally nothing to recommend it.” Many people love to get all worked up about Chainsaw, but they’re not nearly as irritating as those who fawn on it, mumbling about “a leap forward in genre integrity” and “certain primal needs.” Frankly, I prefer Harper’s ragings about the “scabpicking of the human spirit.”

Suddenly people were jamming the theaters to see Chainsaw, and we realized we might make a lot of money. And we saw that the movie would become much, much more than we had ever expected. But we had no idea what, exactly.

Rumors spread among the crew and cast about how much money the movie was making. We began to calculate what we would get, I had half a point, and that would be a lot of money if the first weeks’ theater figures were accurate. The first quarterly check, and the many after that, I was convinced, would amount to more money than I had ever seen.

The first quarter ended with no check. But these things, we actors were assured, took time. After all, the production company people said, the first money would be held by the theaters for ninety days before they had to send the distributor 60 per cent of it. Then the distributor would not send us our 60 per cent of that money for another ninety days. So we would not see any money until at least six months after the release. And it might even be nine months before the increasing momentum of the film’s success would be reflected in the royalties.

Finally, after nine months, the first checks arrived, the ones we had been waiting so long for, the ones that were to be so big. My check came to $47.07.

I began to suspect that something was wrong.

In the meantime, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre continued to make money. Some people were estimating a gross of between $15 million and $50 million—not bad for a movie that had cost less than $100,000 to shoot. But the distributor’s accounting reports were impossible to verify. No one could tell how much money the movie was really making.

Accusations started flying. The production company said the distributor was ripping us off. There was talk that the distributor had hidden income and had double- and triple-entered expenses. Others, actors included, charged that the production company had sold us out, had made a deal bypassing the small shareholders.

The accusations grew heavier and tempers grew hotter. Some actors wanted to sue the production company, though the company kept assuring us that it was as mystified as we were. We were told that either the movie was not making the money we thought it was or the distributor was ripping us off. So the production company filed suit against the distributor.

Today, after years of rumors, charges and countercharges, lawsuits, and out-of-court settlements, no one yet knows who did what to whom. I certainly don’t pretend to. Nor is anyone ever likely to know how much money Chainsaw made. All we know is that we saw almost none of it.

Still, it’s not so bad. I remember thinking early on, when I realized we weren’t going to see any money, that my movie career was doing just fine. At least I could legitimately call myself a film actor, and that had certain advantages. For instance, there’s nothing quite so appealing and interesting to women as a movie actor.

Soon after the movie came out, a friend decided that since I was now a Movie Star, I should use that to my advantage. One night he drove me to an apartment building in Austin and introduced me to one of the most strikingly beautiful women I had ever met. I caught my breath and had a hard time speaking. Not that it mattered. I didn’t have to say a word. When she heard that not only was I an actor but also I had been in that film, she got very friendly. She snuggled up to me, stroking me with her voice. I mutely agreed to take her to see the movie the next night.

When I arrived to pick her up, she was almost panting—and so was I. She suggested a quick drink and said we should come back to her apartment after the show and settle in on the couch. I could see where this was leading, and I could see I was going to like being a Movie Star. She rubbed against me as we drove off to experience The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Close together in the darkness of the theater, we watched me on the screen. We watched as I killed my first victim with a hammer. We watched my favorite scene, in which I impaled a girl on a meat hook. We watched as I used the chain saw to carve up another victim in his wheelchair. We watched the whole nasty little story unwind.

She was strangely quiet on the drive home. I didn’t mind, though. I was occupied with thoughts of what we were going to do when we got behind the locked door of her apartment. As we walked to her door, she fished her keys from her purse. She slid the key into the lock.

“Thank you,” she said. “It was very interesting.”

She opened the door slightly and turned toward me. She then slipped through the door and slammed it shut. Evidently she had not liked the movie.

And, as many others would in later years, she had confused me with the character I had played. So now when I meet a woman who wants to see the movie with me, I suggest she not see it. It’s just another horror movie, I tell her, the kind I would never go to myself, had I not been in it. I can’t stand horror movies, I say. They scare me.

It usually works.

Now, whenever I see Chainsaw, I’m struck by a certain irony. It seems I have, after all, gained a measure of fame. And that is something most of us would love to have, if we’re honest about it. I wanted it. But I’ve paid a price. I know every chain saw joke there is, and none of them is witty. I cringe when someone calls in the middle of the night to talk about the movie or to offer up chain saw sounds. Every time someone asks me for an autograph or asks if I really was in that movie, I feel both the thrill of acceptance and a sense of disappointment. It’s more than just a loss of privacy; the attention locks me into being, in most people’s eyes, nothing more than that fellow who killed people back then. I’d like to be free of all that, but I also admit that there is some small comfort in it, a confirmation of myself through the attention of others.

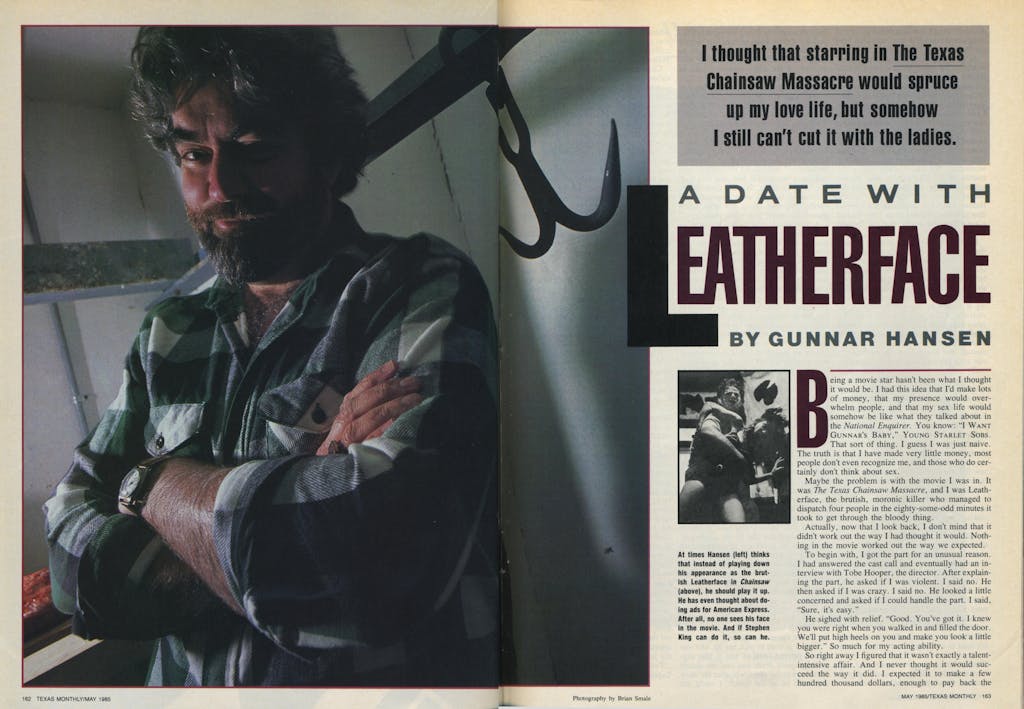

Sometimes I even think that instead of playing down my role in Chainsaw, I should play it up. I think of that whenever I see Bubba Smith rip off the top of another Miller Lite can. When I first saw him do it, I realized that that was what I should be doing. So I wrote to Miller’s ad agency, suggesting that maybe the killer from Chainsaw should be cutting the tops off the cans with a chain saw and making appropriate jokes. They never answered my letter.

I’ve thought of other ads too. American Express—no one sees my face in the movie, and if Stephen King can do it, so can I. Or McCulloch chain saws. I can see that one easily enough. We’d use a clip of the film, leather mask and all, and cut from that to a shot of me in a backyard scene talking about all the nice lawn furniture I made with my Mini Mac.

The possibilities are endless.

Realistically, of course, I know I can’t expect much in the way of future dividends from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. If the movie was worth doing, it’s because of what I’ve gotten from the experience so far. Often I was miserable, as we all were, while making it. We struggled through shooting sessions that sometimes dragged on for 26 hours straight. We put up with stinking food rotting under the lights and with stinking costumes that we couldn’t wash for fear of damaging them. One night, precariously balanced on my high-heeled boots and peering through a mask that almost blinded me, I fell and pitched the chain saw up into the darkness above the lights. I covered my head and waited for it to hit. It landed beside me, still running. All of us took risks like that. During the six weeks of shooting, we were ground down by the heat and exhaustion, and at times we wondered why we were doing it at all.

But it definitely was worth making. I got so much out of it that whatever misery I went through didn’t amount to much. It was the first time I had worked with people who were good at what they did. I saw that I wanted more of that. It taught me a lot about film and, in its aftermath, about the film business. It also taught me a lot about fame, about my privacy, and about what is valuable to me.

And I think Chainsaw, in spite of all the jokes from my friends, is something to be proud of. It is much better made than some people are willing to admit. In spite of the revulsion of the critics, the movie is not particularly graphic. No limbs are shown being cut off, no heads explode the way they do in more respectable movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark. There are a couple of scenes that make even me wince, and there is plenty of blood, but almost everything in the movie is implied, an illusion. It’s more funny than scary.

Nor does it bother me that I was in such a movie. If Chainsaw is part of America’s much-perceived moral decay, the movie itself cannot be blamed. It is, at worst, only a symptom of that decay (that “wet rot,” as Harper’s put it). I doubt that it is even that. Maybe it’s just a way for the viewer to get the hell scared out of him and to come out feeling a little different. Maybe it fills some need people have. Or maybe the movie is merely worthless. But to assert that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is evil or hurtful is just plain foolishness. In fact, I would do it again. Sure I would.

But with a better contract.

- More About:

- Film & TV