I was a Brent Grulke fan before I ever knew him.

The official obituary for the SXSW creative director, who died of a heart attack last month at the age of 51, said he was inspired to move to Austin and attend the University of Texas in 1978 after reading Jan Reid’s book The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. By the time I moved to Austin to attend UT in 1990, Brent had played that very role for me.

The so-called “New Sincerity” bands, among them Glass Eye, Doctors Mob, the Reivers, Wild Seeds, and True Believers, were all I knew of Austin besides Darrell Royal, and much of why an R.E.M.-obsessed Jewish kid from Philadelphia could someday think of calling Texas home (though I also had copies of Larry McMurtry’s All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers and Steve Earle’s Guitar Town). Grulke was a friend, fan, road manager, soundman, coach and shrink to those bands, all of whom will pay tribute to him—along with Fastball, Sixteen Deluxe and Wannabes—Saturday at ACL Live at the Moody Theater for what has been dubbed “Grulkefest: A CELEBRATION OF BRENT / 1961-2012.”

Unbeknownst to me, Brent was the co-producer and liner notes writer of the 1985 compilation Bands on the Block, which I used to play on WNUR, the Northwestern University radio station that was my whole college existence. When I saw the Reivers live in Chicago, he was probably behind the soundboard. And he co-wrote “I’m Sorry, I Can’t Rock You All Night Long,” the 1988 not-really-hit by Wild Seeds, the band fronted by Texas Monthly’s Michael Hall.

For me, however, he was just an editor I needed to impress in 1990. I was a journalism grad student looking to catch on at the weekly Austin Chronicle, and he had just been put in charge of music coverage–kind of a bummer, from my perspective, because I had been prepped by mutual friends to talk to Michael Corcoran, who I knew from his article about the Austin music scene in SPIN. But “Corky” (also now a Texas Monthly contributor) had left town.

There was no reason to worry. As an obsessive music fan and fan of music journalism, Brent was quite familar with my sole outlet outside of Northwestern’s college paper- the independent magazine Option, which had given me my first assignment after shooting down my pitch to interview none other than Glass Eye. Glass Eye was one of my favorite bands (Austin or otherwise) so that first conversation with Brent in the Chronicle’s cramped office near the University of Texas campus contained what was, for me, a massive revelation.

“No way!” I found myself exclaiming. “You’re married to Kathy McCarty from Glass Eye?”

The marriage didn’t last, but Brent’s regard for Kathy’s music did. When, after his death, I found myself looking at the Google+ profile I didn’t even know he had (Brent never used Facebook or Twitter) it turned out the second to last thing he ever posted was Glass Eye’s video for “Christine,” along with the plainspoken comment: “Just Listen.”

The song’s opening lines: “Time has stolen you from me….”

The Chronicle and SXSW being sister organizations, Brent did work for both, and so did I part-time for several years. He eventually became the top guy on the music side, credited with transforming SXSW into the huge event and international phenomenon it is today. This is why his death was news in Pitchfork, Billboard and the New York Times.

At one of the many gatherings the week Brent died, one friend of ours, Ron Marks of the band Texas Instruments, went so far as to argue that SXSW was the single thing that saved Austin’s economy, bringing it both tourists and its huge creative-class cache. Another, former Daniel Johnston manager Jeff Tartakov, said the communal grief reminded him of nothing so much as the death of Stevie Ray Vaughan almost exactly 22 years earlier (which was the week I moved to Austin, as it happens).

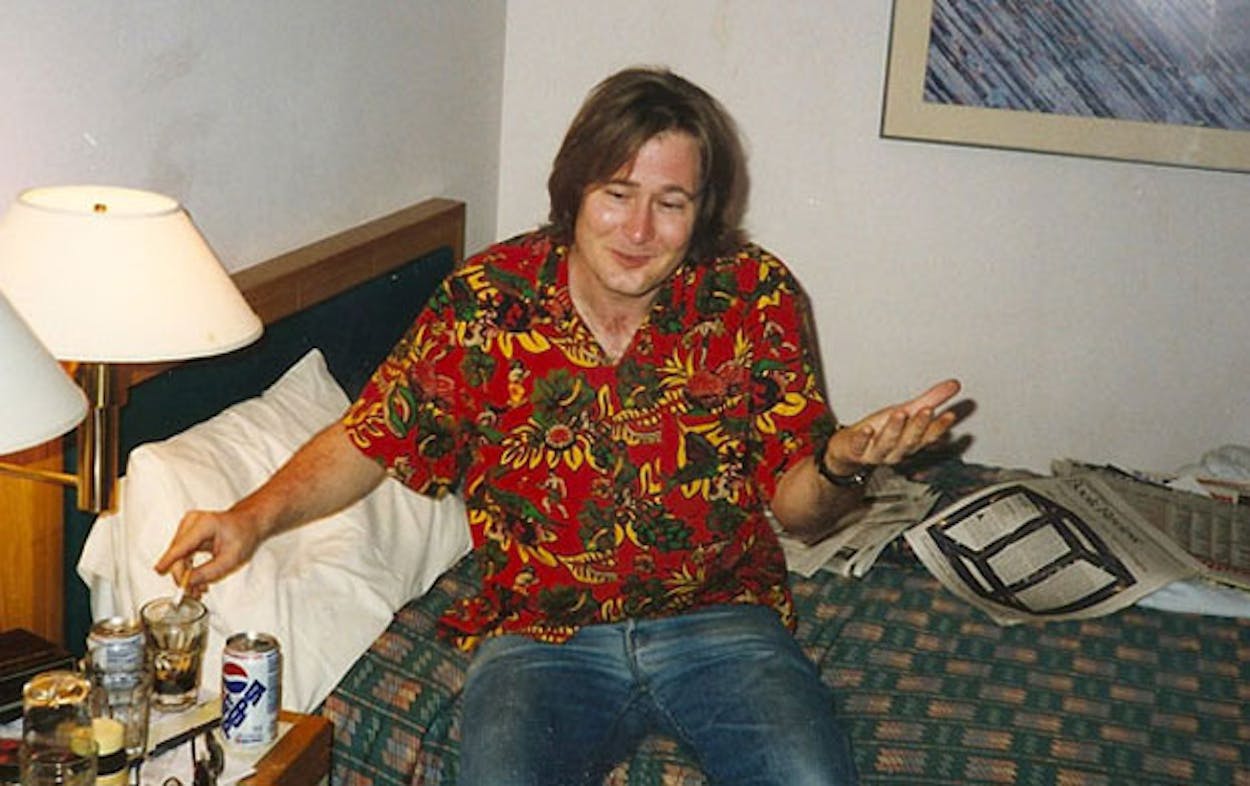

Because of Brent, it was always hard for me to buy into a certain segment of the Austin music scene’s malevolent, conspiratorial perception of SXSW, even though I knew that they were also businessmen. Brent was Brent. When he wasn’t getting flown to the Olympics by the British government (the last big trip he took) or getting VIPed at festivals in Barcelona, he was still the same goofy but ragingly intelligent (and often drunken) guy I went to shows with at Hole in the Wall or Liberty Lunch, or talked about post-modern fiction with.

“Brent was a true and loyal man,” Austin musician Jeff Smith of the Hickoids, who co-produced and released Bands on the Block, wrote in an email shortly after Brent died. “It would have been easy for him to turn his back on many of us as the importance of his job grew, but he just wasn’t that guy.”

When I moved away from Texas between 1993 and 1995, leaving all my stuff in storage, Brent’s house became my Austin home. For two weeks in the summer of ‘94 I slept on his bedroom floor (since that was the only room with air conditioning); in ‘95 I lived there for a good six months while looking for a place to buy. My cat, a vicious calico named Paddy, would regularly joust with Brent’s own hellbeast, a little grey thing by the name of Butch, costing both of us sleep.

I also wrote what was then my greatest journalistic feat, a Rolling Stone cover story on Courtney Love and Hole, at Brent’s dining room table. Courtney didn’t like that story, but when the Lollapalooza tour came to town, Brent and I somehow wound up taking members of Hole, Pavement and Elastica back to his house, where Elastica’s Justine Frischmann haughtily examined Brent’s CDs and then demanded, “Where are your Wire records?”

(If you’re not famiilar with Elastica—or Wire—this would be like Pat Green marching into your living room and saying, “hey, got any Robert Earl Keen?” And Brent’s Wire records were in the other room, with all the vinyl.)

The last time I saw Brent was June 26, when he came out to the Mohawk after midnight to see Wussy, a band from Cincinnati that I’d written a big feature on a few years back. Brent didn’t really need to see them—heck, they’d just played SXSW, with a crappy Tuesday slot at an annoying 6th Street club, prompting the band to joke, correctly, that they were drawing better this time.

So I knew he’d probably come out on my say-so, and because he’d read my story, which had also—big point of pride—been quoted several times in a piece that Robert Christgau, the “Dean of American Rock Critics” (and one of the earliest SXSW keynote speakers), had written about Wussy. Maybe a little part of Brent even saw that and thought, “I was that guy’s first editor.”

But even more of my Brent memories are about sports. He was both a UT fan and Husker, having grown up in Nebraska before ending up in Houston. He was with me at the infamous 66-3 UCLA-Texas game that got John Mackovic fired. And I remember sitting on his couch in 1994 watching my own home-state team, Penn State, give up a few late touchdowns to Indiana that made the game look closer than it was, which eventually allowed Nebraska to surpass the Nittany Lions in the polls and win the national championship. Despite that bitter pill, I also remember Brent being over at my apartment one year later, and me joining him in going nuts at the Huskers’ repeat championship, which featured QB Tommie Frazier’s absolutely crazy run.

Brent was also a big Astros fan, which, of course, had many people joking that’s what killed him (and me saying, “at least he didn’t live to see the designated hitter”). At his funeral, one friend and SXSW co-worker, Craig Stewart, made the whole room smile when he walked into the church wearing a ‘Stros jersey (especially since Craig’s a Rangers fan). That very day, the Astros lost to Arizona 12-4, and manager Brad Mills got fired.

With no Oilers to root for, Brent had also become something of a Green Bay Packers fan, mostly because Mike Hall and another close friend, Scott Anderson, were Packers nuts. When I got to go to a game in Green Bay with my father (Lambeau was on his bucket list), it was Brent who kept texting me from Austin, wanting to know all about the whole experience. I’m usually one of those people who believes that when it comes to sports, your team should be your team, your tribe your tribe. But Brent’s tribe was his family and friends. Being around his friends loving the Packers made him love the Packers. He loved sports as sports, and cared deeply about rock and roll as art (almost to a fault), but he also knew that both things were about community.

What I remember more than anything is one night in the living room of Brent’s house, me no doubt drinking Mountain Dew at 2 a.m. to write (I switched to coffee around 1997), him back from the Dog and Duck. Though I can’t recall the incident or circumstance that led to the discussion, we were talking about friendship, and Brent said that the simplest measure of your closest friends was, “Who would take my call at 4 a.m. from jail?”

Most of us can probably agree with that, and would mentally tick off a list of people using no more than two hands (and possibly just one). Brent’s list may have been that size as well. But he would have been on EVERYBODY else’s. Most of us will be at GrulkeFest, both on the stage and in the audience, on Saturday.