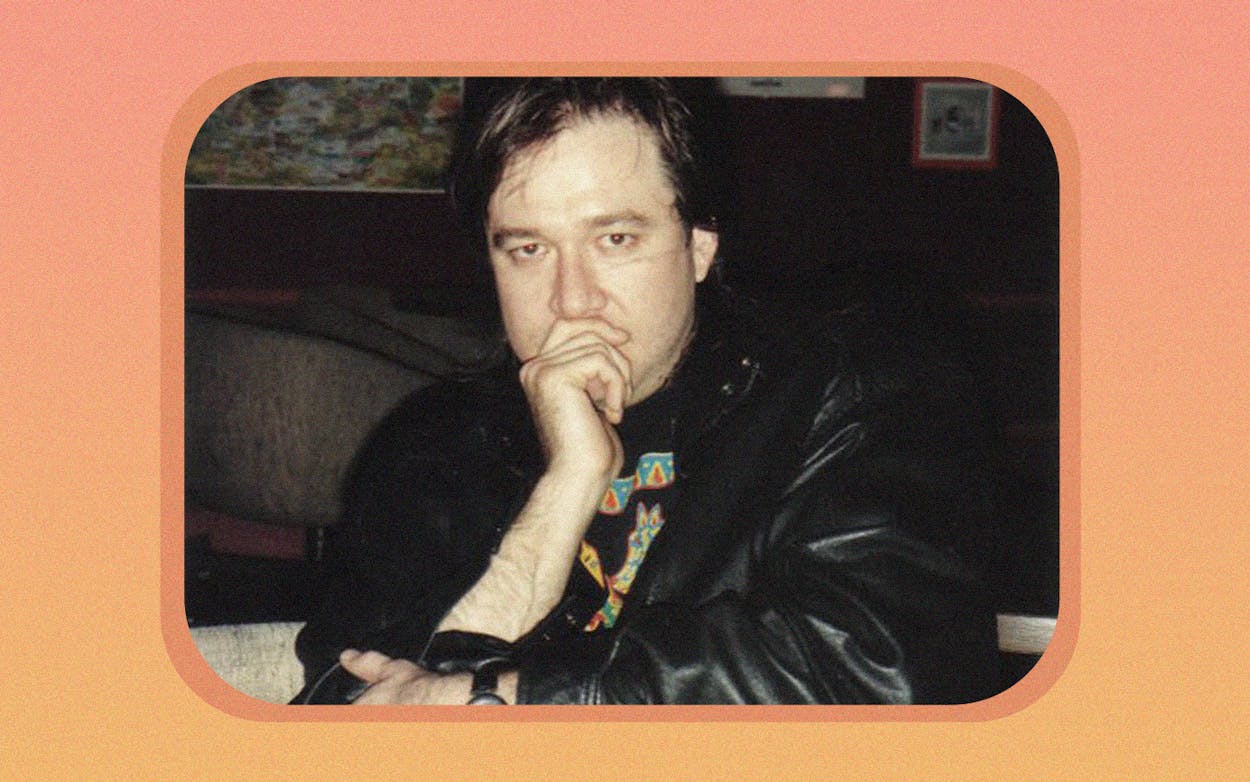

Bill Hicks was the subject of a lot of mythologizing even before there were actual weird myths about him. The legendary Houston comic, who died in 1994 of pancreatic cancer at the age of 32, was the subject of famous tributes on the iconic rock band Tool’s 1996 album Ænima. In the beloved nineties comic book series Preacher, a chance encounter with the comedian is a plot point that sets the protagonist on his adventure. Stand-up comedians ranging from Joe Rogan to Patton Oswalt to David Cross to Ron White to Russell Brand worship at his altar.

For a comedian who toiled mostly in obscurity, his outsized impact on culture has led to a massive effort to preserve his body of work—there are nine albums of his material, as well as an exhaustive 2010 boxed set, four official video performances from throughout his career, and at least two documentary films detailing his life and work. But a video that made its way to YouTube for the first time this month reveals an early look at the comedian’s evolution as a performer. While the 1985 set from an Indianapolis comedy club isn’t exactly unreleased—it was part of that 2010 boxed set—it’s certainly a rare glimpse at Hicks before he became the figure many comics would cite as an inspiration.

Hicks was famous for his blend of psychedelic philosophy, insight, and cynicism. Tool worshipped the guy for his routines about how psilocybin mushrooms could help listeners “squeegee their third eye,” and comics were excited to see someone who genuinely didn’t seem to care if audiences liked him. Hicks didn’t invent making jokes that double as incisive criticism of institutions—Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, and George Carlin were all famous before he even picked up a microphone—but in his final years, the comedian was fearless in delivering that material. He would attack religious hypocrisy on abortion, declare his disdain for the people who came to see him perform, and proclaim that audiences needed to take hallucinogens until they realized “we are all one” and the economy is fake. It’s still riveting to hear someone say those things so boldly now.

But Hicks wasn’t born that kind of performer, and the 1985 set from Indiana—taped when he was just 23 years old—is a rare look at the early stages of his comedic evolution. There are hints of the performer Hicks would become. His material is still political, with jokes about Ronald Reagan and Reagan’s would-be assassin John Hinckley performed when that sort of punch line was still transgressive; it’s still focused on shocking people who tolerate prejudice and hypocrisy. (At one point, Hicks describes an encounter with an anti-Semite who said he hated Jewish people because “they killed God”—”If I believed that Jews killed God,” Hicks says while fiddling with a cigarette, “I’d worship the Jews.”)

But it’s also much more of what you would expect from a 23-year-old comedian in his early days on the road. Does Hicks hurl obscenities at audience members? He does not; instead, he asks people in the crowd what their majors are, and offers only the gentlest of jabs—he asks a finance major if she’ll be picking up the check—and performs with the openhearted softness of a young man who seems like he wants people to like him, and who dreams that maybe someday he’ll end up famous.

Hicks did end up famous, in his own way—even if much of it was posthumous—but it didn’t come from making mass audiences like him. Hicks, in the video from Indiana from 1985, makes jokes about how corny his parents are, about the differences between cats and dogs, about how Keith Richards will outlive everyone but the cockroaches. It’s still funny material, and if you watch it knowing nothing about Bill Hicks except that many of today’s most famous comics cite him as an influence, you might assume that he simply sharpened his act, stopped swearing so much, and grew out of some of the edgier material—not that he steered his onstage persona sharply in the direction of all the things that garner polite chuckles from the Indianapolis comedy club crowd, instead of the jokes that made them erupt in belly laughs.

That there’s a readily accessible document of a time in Hicks’s career when he could have gone in either direction is an exciting thing for fans who know him only as a ranting, raving prophet of psychedelia, hoping to send a message of universal brotherhood by getting in the faces of people who came to see him perform. That side of Hicks is just barely visible in his earliest performances—and now you can see that for yourself.