This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

As he has for more than thirty years, Edward Albee is sitting in a darkened theater, his hands neatly folded in front of his face, watching actors bring his characters to life. It is April 1992, and the two-time Pulitzer prize winner has come to the Wortham Theatre at the University of Houston, where he is a Distinguished Professor, to see a mostly student cast rehearse his latest writing and directing effort, The Lorca Play. The play, his twenty-fifth, is an epic about the life of Federico Garda Lorca, a Spanish poet and playwright who was murdered by General Francisco Franco’s fascist thugs, and it is filled with commentary on politics and art and life—especially on a life in the arts.

As Albee observes impassively, a student portraying young Salvador Dalí, a García Lorca contemporary, runs through his lines. “Unfortunately,” the actor says, “most of you know me from the end of my life—the silly man with the hugely upturned moustaches, the fake, the artist turned con man, the charlatan, the eccentric who made a career of the eccentric, the fool. My art ran out of steam, but I kept right on painting.” The moment is striking, and not just because the student bears an uncanny resemblance to the painter. It is impossible to hear that last line and not think of the career of the man who wrote it.

During the sixties, with the New York premieres of The Zoo Story, The American Dream, and, most sensationally, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Edward Albee was one of the most celebrated playwrights of his generation. In 1962, when he was 34 years old, a Life magazine article on his “meteoric” career said he “has a merciless ear for the clichés, non sequiturs and droning repetitions of everyday talk.” The next year Newsweek described him as “the new O’Neill, the young Strindberg, and, inevitably, the northern Williams.” It went on to quote the southern Williams—Tennessee—as saying, “Edward Albee is the only great playwright we’ve ever had in America.”

But by the end of the decade, Albee’s career was beginning a steep and seemingly irreversible decline. The critics and the public were waiting for him to top Virginia Woolf with a work of equally scathing wit and power. Instead, they complained, his writing became attenuated, his characters excuses for metaphysical musings. In 1980 critic Stanley Kauffmann wrote in the Saturday Review, “Fate has not been kind to Edward Albee. I don’t mean only the bitterness of early success and subsequent decline, though that’s hard enough. Worse: he was born into a culture that—so he seems to think—will not let him change professions, that insists on his continuing to write plays long after he has dried up.”

Many artists have been destroyed by such attacks, but not Albee. In defiance of the critics, he has continued to write as well as direct, lecture, and teach. The Lorca Play, for example, was commissioned by U of H and coproduced by its School of Theatre and the Houston International Festival. Although the play’s debut last year came and went without a ripple of interest from the New York theater establishment that once embraced him as its savior, Albee is clear in his mind about where he stands and where it stands.

“I have an awareness of my own virtues and failures and excellence,” he says from his seat in the Wortham. As he speaks, an edge creeps into his archly patrician voice, unusual for a man whose conversational style is that of ironic understatement. “I’m not confused by fashion. It’s very frustrating to take the trouble to communicate with people, to have done a fairly good job and face critical anger, stupidity, to get cut down. It’s annoying, and people are cheated. If you don’t get crushed, it enrages the people trying to crush you anyway. This happens to anybody and everybody who comes along. There’s always the great white hope.” Then he adds a piece of advice that he gives to his students: “Unless you have to be a playwright, don’t do it. It’s a tough racket, a heartbreaking one.”

Albee assures, however, that his own heart hasn’t been broken. In the latter part of his life, he has come to Houston, where he does not have to dwell on the pain of failure and rejection. In Houston Albee is not an artist who never fulfilled his early promise; his gifts are celebrated for being as fresh as when he first astonished the world. Houston is a haven where he can direct, and write, the plays he wants to see performed, far from the savage judgments of Broadway. More important, it is a place where his name still carries a lengthy suffix. To students, faculty colleagues, administrators, and social heavyweights, he is not a man whose art has run out of steam. He is, as they proclaim at seemingly every opportunity, Edward Albee, the Greatest Living Playwright of the Twentieth Century.

Either you do or do not develop the notion that if you learn something, you have a responsibility to share it,” Albee says, striding quickly toward his morning class. “I’ve done workshops and lectures over the years, but this is my first faculty position. Being selfish, I do something only if it’s useful to me. Altruism has its limits.”

Albee’s association with the university began in 1985, following a call from Sidney Berger, the director of U of H’s School of Theatre. “I got his number and he answered the phone,” Berger recalls. “I didn’t know what to say.” Berger recovered his wits enough to ask Albee to direct three of his one-act plays at the university. Albee’s performance was a success—as Berger told him, “You’re a genius and I’m in awe.” Having made a connection with a man he has described as “a god,” Berger was not about to let him go. Three years later Albee was offered a professorship, and he accepted—though the fact that he never graduated from college presented something of a problem. “I’ve been thrown out of every college I’ve ever attended,” he told Berger. The U of H administration, deciding two Pulitzers constituted an equivalency degree, waived the usual academic requirements.

Albee’s time at the university is partially taken up by directing—this February he staged a production of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. But most of his time is spent on the two classes he teaches on Mondays and Wednesdays each spring semester. In the morning he leads a playwriting class. In the afternoon he supervises the mounting of six student plays in a production workshop. He usually arrives in Houston on Sunday evening and leaves Wednesday afternoon, sometimes for one of his homes in Coconut Grove, Florida, Manhattan, or Long Island, where he endows a foundation that provides a working retreat for writers and visual artists. His stamina is phenomenal. Throughout the year he has a heavy lecture schedule around the country and often directs revivals of his plays.

The application process for Albee’s classes is uncomplicated: a writing sample, preferably a play. One of his conditions for teaching at the university was that he choose his own students. He gets about 150 submissions for his classes, and from those he selects about 15. “I turn down an awful lot of thoroughly competent stuff,” he says. “I’m interested in incipient playwrights, people who think like playwrights. That’s why I turn down a lot of well-constructed middlebrow plays. I don’t want them to write like me. I want them to write their plays and realize their intentions more fully. I can’t create a playwright. I can be useful in getting someone a little closer to his mark.”

The structure of Albee’s playwriting class is fluid. Some days he simply lectures; others are spent discussing students’ plays or reading them aloud to see how they work. Albee’s instruction method is a combination of the Socratic and the inscrutable. Former student Tom Bell, who has had eight plays produced since taking Albee’s class in 1989, remembers being depressed the first time he heard actors speak his words: “I was prepared to tell [Albee], ‘Replace me.’ But he looked me in the eye and said, ‘If I didn’t think you were a playwright, I wouldn’t have picked you.’ That meant everything to me.” Another ex-student, Elizabeth McBride, recalls a similar moment: “He said to me once that my writing was so subtle it was ‘like the difference between running your hand over a piece of silk or a piece of velvet.’ That can keep you going for a long time.”

During the production process, Albee gives his students free rein, checking in to see how things are going but rarely volunteering advice. Bell says Albee is like a parent gently pushing his children toward independence. “He really gets a thrill out of watching them grow and learn,” he says. “He lets you make your own mistakes. He’ll watch rehearsal and then say, ‘What’s wrong?’ Either you tell him or you say nothing, in which case he’ll walk away, figuring you’ll figure it out.”

And like a good parent, he is there to rescue you when things go really wrong. Two days before Bell’s debut as a playwright, Albee stopped by to watch a rehearsal of The Sick Room, about several men on a detox ward. One of Bell’s actors did not need any coaching to play someone mentally unstable—in the middle of rehearsal, he simply walked out. “Albee said, ‘What the hell is this?’ ” Bell recalls. “I went and found the actor sitting under a tree eating Chinese food.” Albee took Bell and the play’s director into an empty hall and laid the script, page by page, on the floor. “He was on his hands and knees,” Bell says. “He pointed and said, ‘Cut from there to there.’ It was this guy’s scenes. I was fond of the character, but this was two days before opening. Albee was teaching me what to do when s— happens. He’s never told me anything about making theater that isn’t true.”

At one Monday morning class, as his students listen with various degrees of attentiveness, Albee speaks for an hour without notes. He is dressed casually: green denim work shirt, olive-drab pants, black Reeboks. He alternately sits on the edge of his desk and paces the front of the room as he talks. As he moves through four centuries of theatrical history, from Shakespeare (“In his day, plays had to be about people of importance”) to the modernists (“Only the Broadway middlebrow has trouble with the reality of Beckett”), an unmistakable subtext emerges: Why his own career has fallen into decline (“Chekhov, Pirandello, Brecht, and Beckett: These are absolutely essential for understanding modern drama. Of course, you’ll never know these changes had taken place if you go to the modern theater because their plays are rarely performed”).

Albee’s performance is impressive, all the more so for its informality. “Any questions, comments? I’m vamping here,” he says at the conclusion. A student wants to know more about ambiguous endings. “Lack of resolution is not necessarily good,” Albee says. “The difference between interesting ambiguity and unintentional ambiguity is very important. Ambiguity demands as much control as anything else does.”

Another student asks Albee’s opinion of Neil Simon’s trilogy of plays about the coming of age of a young comedy writer. “It’s more interesting to a lot of people than it is to me,” Albee says. “We’re all terribly unpleasant about Neil. We’re so terribly jealous.”

A third student, a man in his fifties, offers his own observation: “I think the two greatest plays of the twentieth century are The Zoo Story and Virginia Woolf.” Albee seems both embarrassed and pleased. “That won’t get you a good grade,” he replies.

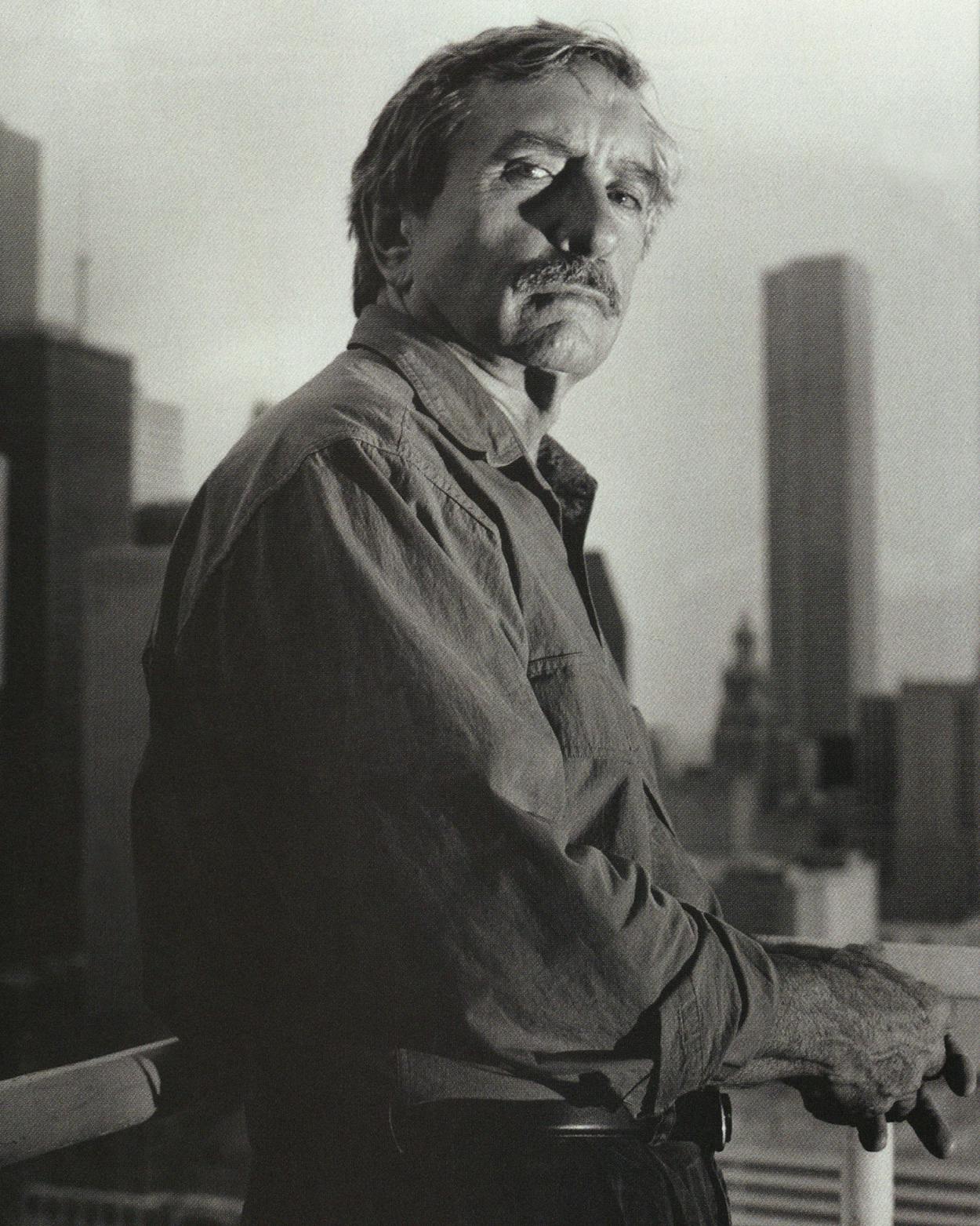

If the years have been brutal to Albee’s psyche, there is little physical evidence. At 65, he is a remarkably youthful-looking man. This is nothing new; in 1963 Newsweek described him as “almost insultingly young-looking.” In 1980 People attributed his ageless looks to good health habits, including bed before midnight. He is something of a health fanatic; while in Houston, he works out four days a week at the Fitness Exchange. He never drinks or smokes, and actors say that when he eats at rehearsals it is usually an apple or a cup of yogurt. He is trim and compact, although in photographs his large head gives the impression that he is a much taller man. He has always been handsome, with strong, well-shaped features and deep-set blue-green eyes, which are magnified by oversized aviator glasses. His look is circa Sgt. Pepper, with his longish, rather unkempt salt-and-pepper hair and drooping moustache.

Albee, more formally Edward Franklin Albee III, was born in Washington, D.C., adopted two weeks later, and raised in Larchmont, New York. He never knew his birth parents; statements he has made through the years indicate that his adoptive parents never knew him. “I never felt that I belonged to my adoptive family anyway,” he told American Theatre in 1992. His father, Reed, an heir to a famous chain of vaudeville theaters, was a small, meek man overwhelmed by his large, voluble younger wife, Frances.

Albee has explored his family’s dynamics in many of his plays. In The American Dream, a pretentious woman and her henpecked husband adopt a “bumble of joy,” who turns out to be a bitter disappointment. The family reappears in The Sandbox, a short play in which a middle-aged mother plans to abandon her own elderly mother at the beach. It could even be argued that the imaginary son in Virginia Woolf is a version of Albee himself.

In his teens Albee wrote bad poetry and two awful novels. In his twenties he held a number of jobs, including one delivering telegrams for Western Union. Then, as a thirtieth birthday present for himself, he wrote a one-act play, The Zoo Story, about an explosive encounter between a drifter and a middle-aged publishing executive. After a circuitous route through Berlin, the play arrived Off-Broadway in 1960. It was a sensation, and Albee was launched.

The critical expectations for his career were enormous, and with the 1962 Broadway debut of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, they were fulfilled. Even thirty years later, the psychological warfare conducted by the long-married George and Martha—he a failed academic, she the daughter of the university president—remains vital and funny. The play takes place during a long drunken evening, when Martha and George invite over a young couple new to the faculty. In one exchange, Martha has told their guests, Nick and Honey, what a poor husband George has been.

GEORGE (To Nick . . . a confidence, but not whispered). Let me tell you a secret, baby. There are easier things in the world, if you happen to be teaching at a university, there are easier things than being married to the daughter of the president of that university. There are easier things in this world.

MARTHA (Loud . . . to no one in particular). It should be an extraordinary opportunity . . . for some men it would be the chance of a lifetime!

GEORGE (To Nick . . . a solemn wink). There are, believe me, easier things in this world.

NICK. Well, I can understand how it might make for some . . . awkwardness, perhaps . . . conceivably, but . . .

MARTHA. Some men would give their right arm for the chance!

GEORGE (Quietly). Alas, Martha, in reality it works out that the sacrifice is usually of a somewhat more private portion of the anatomy.

An Oscar-winning movie version of the play, starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, soon followed, giving the work an eternal life in popular culture—but also making it an artistic albatross for Albee. He won a Pulitzer in 1967 for A Delicate Balance, about the unnamed dread that comes over all of us as we grow older, and another in 1976 for Seascape, in which a couple on the beach encounters a pair of married lizards (actually, actors in lizard costumes). Yet despite these prizes, the critical disappointment had already started—the feeling that his characters were becoming mere literary devices. The disappointment soon turned to venom. The Lady From Dubuque, about a family whose young mother has cancer, received brutal reviews and closed after eleven performances in 1980. Albee was quoted as saying of the experience, “The only time I’ll get good reviews is if I kill myself.”

If possible, things hit a new low two months later, with the Broadway opening of Lolita, Albee’s adaptation of the Vladimir Nabokov novel. It closed after nine performances and was considered a fiasco. More failures followed. The Man Who Had Three Arms, in which Albee savages theater critics, was savaged by critics in turn and had a very brief New York run in 1983. He has not had a play produced on Broadway since.

Of Albee’s more recent plays, a question arises as to whether they would have been produced had they not carried the name “Edward Albee.” Take the case of Albee’s Marriage Play, which had its American premiere last year at the Alley Theatre in Houston. The Alley’s artistic director, Gregory Boyd, was required to advertise it as “Edward Albee’s Marriage Play,” presumably to capitalize on the playwright’s name recognition. “It’s possessive, like ‘Steven Spielberg’s E.T.’ ” he says. “Since Edward became an institution, the titles have changed.” Would Boyd have taken on the play if it had come from a lesser-known author? “I would have thought it was interesting,” he says. “Would I have done it? Probably not.”

Marriage Play is about one day in the long, crumbling marriage of an unhappy couple, Jack and Gillian—the day Jack comes home and tells Gillian he is leaving her. So close is it to Virginia Woolf territory that in the Alley program for the play, Albee describes the annoying conversations he has had with people who make the comparison and how he must instruct them that this new couple “bear no relation to George and Martha.”

He’s right: They have none of the specificity, the invigorating bitterness, of George and Martha. Jack and Gillian seem as spent as their marriage; they talk to each other in a sort of gassy, generic speech.

JACK. I’m not changing my mind . . . I’m changing my life. You must learn the difference.

GILLIAN. Between your mind and your life.

JACK. I will strike you.

GILLIAN. I dare say. Poor darling. Poor me, while we’re at it.

JACK (Mimicking). Who is she? Who’s the chippie?

GILLIAN. Yes!

JACK. There’s no one! There’s everyone, and there’s no one. Maybe that’s it.

It’s poignant to go through Albee’s interviews before the play’s premiere: He told the Houston Chronicle in 1989 that it was heading toward Broadway. Yet Marriage Play received only courteously lukewarm reviews in Texas and then moved to the McCarter Theatre in New Jersey, where David Richards of the New York Times wrote, “Those who would like to see the playwright return to the raw power of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and hurl some thunderbolts about the stage are not going to rally to Marriage Play. . . . It is a work more pondered, I suspect, than felt. ”

“A mixed review has gotten fatal now,” Albee says about what happened to Marriage Play. “David Richards apparently was in a grumpy mood and apparently wanted me to write Virginia Woolf. Since the New York Times determines what goes on to Broadway, obviously it is not going on to Broadway.”

Albee also came under attack for the subject matter of Marriage Play. Why, gay writers asked, does a gay writer keep writing about heterosexual marriage? Albee bristles at the notion that his personal life should dictate his work. “I never thought that gay was a theme anymore than straight was a theme,” he says. “I don’t want writers to get trapped. An awful lot of good writing is published under the gay imprimatur, as well as an awful lot of lousy writing.” His personal life, he says, is nobody’s business—though his friends mention discreetly that he has lived for many years with a painter in New York. “As you may have discovered, I’m a fairly private person. If you’re a public person, you have to be a private person.”

For the most part, Albee has managed to carefully guard his privacy. In 1991, however, he attracted a fair amount of publicity when he was arrested for public indecency on a beach in Florida. Albee says he was simply shaking sand out of his suit in a deserted area of Key West. The charges were ultimately dismissed as groundless, though they were the fodder for numerous jokes at the university. At a subsequent rehearsal of a U of H production directed by Albee, there was a discussion of the need for something spectacular to happen onstage. A student said, “Perhaps Mr. Albee can take his clothes off.” “Why not?” Albee deadpanned. “I’ve done it before.”

A gay playwright without a recent success may not seem like someone who would be the toast of Houston, but the adulation the city has heaped on Albee sometimes approaches the obsequious. Listen to Houston art gallery owner Meredith Long, who gave Albee, a passionate art collector, the rare privilege of curating an exhibition: “One of our roles is to make people like that happy in Houston. He is an authentic celebrity. The level in the room picks up when he comes in. We’re glad to have a person like Albee in Houston. We’d like to have more.”

In modern society, celebrities have taken over the function of saints—that is, their lives are chronicled for moral instruction, not just vicarious pleasure—so proximity confers a kind of blessing. But in Houston’s relationship with Albee, there is something more complicated at work than just celebrity. Quite characteristically, the city has made an excellent deal. In exchange for money, Albee gives Houston more than just art; he gives it moral victory over New York. As Houston sees it, it has saved Albee, salved him, bound the wounds so viciously and wrongly inflicted by that eastern cesspool.

“When I first met Edward, I was in great fear,” Sidney Berger says. “The reputation that preceded him—he’s tough, he’s caustic. When he realizes you’re not there to fight, he’s shocked. [Being here] has mellowed him a great deal. He’s relaxed; his creative juices flow.” Berger recalls Albee’s coming to him in need of $2,000 for a student playwriting workshop. “He had his chin out. I said, ‘Okay.’ He said, ‘What?’ He’s so used to fighting. It made him think this is a good place to be.”

Berger remembers a function at the home of Alexander Schilt, the chancellor of the University of Houston System, that was designed to introduce Albee to some Houstonians with a significant interest in the arts and even more significant bank balances. It was a sort of “Meet the Medicis” evening, Berger says. When it was time for remarks, Albee stood up and said, “Sidney has a dream, and I want to be part of this.” It was almost too much for Berger. “I thought, this is Edward Albee, and I’m punky little Sidney from Brooklyn. ”

Even Schilt becomes a little lightheaded when talking about Albee: “I yearn that Houston has been nurturing to him and his creative genius.” The chancellor once took a trip to Spain with Albee—a fact-finding mission for a contingent from the university and the Houston International Festival—during which Albee researched his Lorca play. “He has a wonderful quiet sense of humor,” Schilt says. “I find him easy to be with, comfortable and exciting. If I could take only a small number of people to be with me for the rest of my life, Edward would be on my list.”

But Albee has also used his charms in a more practical way. “He has never declined any request I’ve made for working with the university on donors and potential donors,” Schilt says. “We have tried to use him as the valuable and scarce resource he is. Our requests are very targeted. He is immensely good at creating a sense of excitement. ”

For his part, Albee views these tasks with a sort of noblesse oblige. “I don’t like to sing for my supper much,” he says. “The chancellor does three or four things a year. I go to what you have to put up with. I don’t think anybody behaves very naturally there. The food’s good. Everyone is there for a specific reason. People are perfectly nice. They may be a little self-conscious. They are there to be with me.”

Onstage at the Wortham, the large cast of The Lorca Play is assembling. In addition to two Lorcas—child and adult—the characters include Dalí, Franco, director Luis Buñuel, and composer Manuel de Falla.

As the first act unfolds, Albee watches from his regular seat in the theater. But as usual, he finds it hard to stay still. He gets up and stands in the aisle, walks to the bottom of the stage, and rests his foot on the short stairway. Mostly he lets the actors run through their lines, occasionally interrupting with a piece of advice.

After the two Lorcas foul up a scene, Albee says, “What’s going on? This has got to go snip-snap.”

The play’s narrator, giving a history of the decline of the Spanish city of Granada into a backwater, says, “It was a splendid time.” Albee advises, “Make sure ‘splendid time’ is ironic.”

America has produced many writers whose despair over their declining powers and reputations has destroyed their lives: Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, William Inge, F. Scott Fitzgerald. But Albee shows no such self-destructive impulses. Although there may be some pain in how his career turned out, friend and former student Elizabeth McBride says, “I’ve always felt he was thrilled to be Edward Albee. It is a pleasure for him.”

That seems to be the case as he sits in the Wortham, watching the Salvador Dalí he has created talk about his life. “One final thing,” Dalí tells the audience. “I was young once; I was very serious; I was very wild and serious; and I was a very great artist.” For once, the look on Edward Albee’s face is not one of distant irony or amused remove. He looks, simply, happy.

- More About:

- Writer

- TM Classics

- Theater

- Longreads

- Houston