When Lars Nilsen was growing up in North Carolina in the seventies, his local multiplex used to program kids’ movies on summer afternoons. Stuff like Swiss Family Robinson or (far more meaningful to Nilsen) Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster that you could watch for a dollar while your parents worked. Nilsen went almost every single day. After one matinee, Nilsen recalls, he found himself outside the theater, impulsively pawing through its trash bins. There he came across a small piece of film history, lying discarded among the soda cups and stale popcorn: a couple yards of celluloid that had been lopped off of the 1956 kaiju classic Rodan. Nilsen was thrilled. Taking it home was a pivotal moment for him, Nilsen says—that feeling like he actually owned Rodan.

Nilsen moved to Austin in 1994. He worked a late shift at Kinko’s; he spent some time driving a cab. But mostly, just like those summers when he was a kid, he watched a lot of movies. In 1997, Nilsen met another film fanatic, Tim League, who, along with his wife, Karrie, had just opened the first Alamo Drafthouse Cinema inside a former parking garage in downtown. Nilsen soon became the Alamo’s first real regular, often hanging out with the Leagues and like-minded obsessives after the show. He started suggesting films that the Leagues should screen, drawing from his deep knowledge of cult curios like ’Gator Bait and Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41. Eventually, League asked Nilsen to do some of the preshow introductions for these. Nilsen proved to be a charismatic emcee: knowledgeable, funny, almost effortlessly entertaining—and what’s more, he could sell the hell out of anything. It wasn’t long before League officially gave Nilsen a job, putting him in charge of programming and hosting the Alamo’s fledgling midnight-movie series, Weird Wednesday.

Like everything about the Alamo Drafthouse, Weird Wednesday has its own, nigh-mythical lore. The story always starts in 1999, when League got a tip about a former movie-house depot out in East Prairie, Missouri, where thousands of 35mm prints had just been abandoned and left to rot. League flew up and bought the whole lot of them. He rented a truck that could safely carry 11,500 pounds, and he loaded it with 20,000 pounds of film, driving his rusty, moldy bounty back to Austin on an overheated engine and straining axles. On his slow ride home, League hashed out a way to justify his impulse purchase. The Alamo would start a free late-night series for adventurous moviegoers, he decided, where he would pluck something from his haul, neither he nor the audience knowing exactly what surprises lay in store. Sexploitation flicks, Italian giallo, lesbian vampires, hillbilly cannibals, psychedelic freak-outs—they would discover these forsaken films together.

“There was a lot of sex, a lot of violence,” says Kier-La Janisse, a former Alamo programmer and genre film expert, recalling that initial Weird Wednesday bounty. “A lot of ridiculous costuming and dialogue—everything fun.” And while the series did bring in the curious cinephiles, it also attracted a lot of rowdy drunks. It was free and it started at midnight, after all. Many of them had also been conditioned by the likes of Mystery Science Theater 3000 to laugh at so-called B movies and “trash” cinema, or to shout snarky jokes at the screen. So putting Nilsen in charge proved to be a genius stroke: standing well over six feet tall, his face framed by thick black glasses and long, death-metal hair, Nilsen made for an unusually commanding host. His obvious passion also made him a natural proselytizer. Nilsen whipped up intros that were knowledgeable without being pretentious, funny without being mocking, and he soon cultivated a similar respect for the material from his audience. “I used to say, ‘Pretend it’s a real movie,’ ” Nilsen says. “There is an interesting vision there, even if it is about underwater Nazi zombies.”

In a culture that had long been dominated by so-bad-it’s-good ironic appreciation, Nilsen stumped for actual engagement. And under his direction, Weird Wednesday quickly became a cornerstone of the Alamo Drafthouse community—“the locus of all the social activity,” as Janisse puts it, where people gathered each week regardless of what was playing. As the Alamo’s size and influence grew, that culture that surrounded Weird Wednesday helped foster a larger appreciation of grind-house fare, which soon became mainstream thanks to filmmakers and Alamo friends Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. And all the while, League’s collection of salvaged prints only continued to swell.

Today, that collection is the foundation of the Austin-based American Genre Film Archive, which describes itself as the world’s largest nonprofit dedicated to preserving the kinds of drive-in movies that once seemed destined for the landfill. And the story of how it all came to be forms the basis of a new book written by Nilsen and edited by Janisse, Warped and Faded: Weird Wednesday and the Birth of the American Genre Film Archive. The bulk of its four-hundred-plus pages is a compilation of the many blurbs that Nilsen, League, and others wrote for the Alamo Drafthouse’s monthly guides—witty, pithy paragraphs evangelizing the likes of Kung Fu Halloween and Psycho from Texas. These are rounded out by essays on Weird Wednesday mainstays such as director Joe Sarno (“the Ingmar Bergman of sex films,” Nilsen writes) and actress and “Queen of the Drive-in” Claudia Jennings, as well as countless, artfully arranged images of posters and stills from the heyday of exploitation cinema.

Warped and Faded is a perfect Christmas gift for your film-geek nephew, or a lovely coffee-table book, depending on your tolerance for blood and shadowy nipples. But its real value lies in its fascinating, six-part oral history tracing the early days of Weird Wednesday through the launch of the American Genre Film Archive, a rollicking tale that pays tribute not just to the Alamo Drafthouse, but to the obsessive scavenging that drives a certain kind of film fan. It’s a book about rescuing things from the trash—about finding the value in stuff others see as disposable.

As Nilsen dredges up the memory of pulling Rodan out of the dumpster, he’s only now realizing this anecdote might be somewhat relevant to, you know, the entire direction his life has taken. If this were a movie, I tell him, it would be the hero’s “origin story.”

“If that were in a movie,” Nilsen says, “you wouldn’t believe it.”

The “genre film” is built on tropes: vampires and zombies; superspies and serial killers; horny college students and redneck moonshiners. Many of them were cranked out fast and on the cheap. Still, it’s all about what you do inside those basic frameworks, and how you overcome those limitations. For most genre-film fans, it all boils down to honesty—some kind of pure, authorial voice that shines through in a surprising way. “You’re often getting this vision right from someone’s brain onto the screen, and sometimes they haven’t thought something through perfectly,” Janisse says. “But it ends up making these amazing moments you would never get in any other film. You get so many weird, happy accidents.”

There is perhaps no better, more tactile metaphor for this idea than the American Genre Film Archive. It started with a vision no one really thought through—Let’s buy a warehouse full of rotting films!—and it accidentally became an institution, thanks to its founders’ idiosyncratic will. More than a decade after its 2009 founding, AGFA’s board of advisors includes filmmakers such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Nicolas Winding Refn, as well as the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA. It distributes thousands of films each year to museums, festivals, and art-house theaters all over the world. It is one of the most active film archives in existence, sending out more films annually than even the Academy of Motion Pictures, League says. And it all just sort of happened.

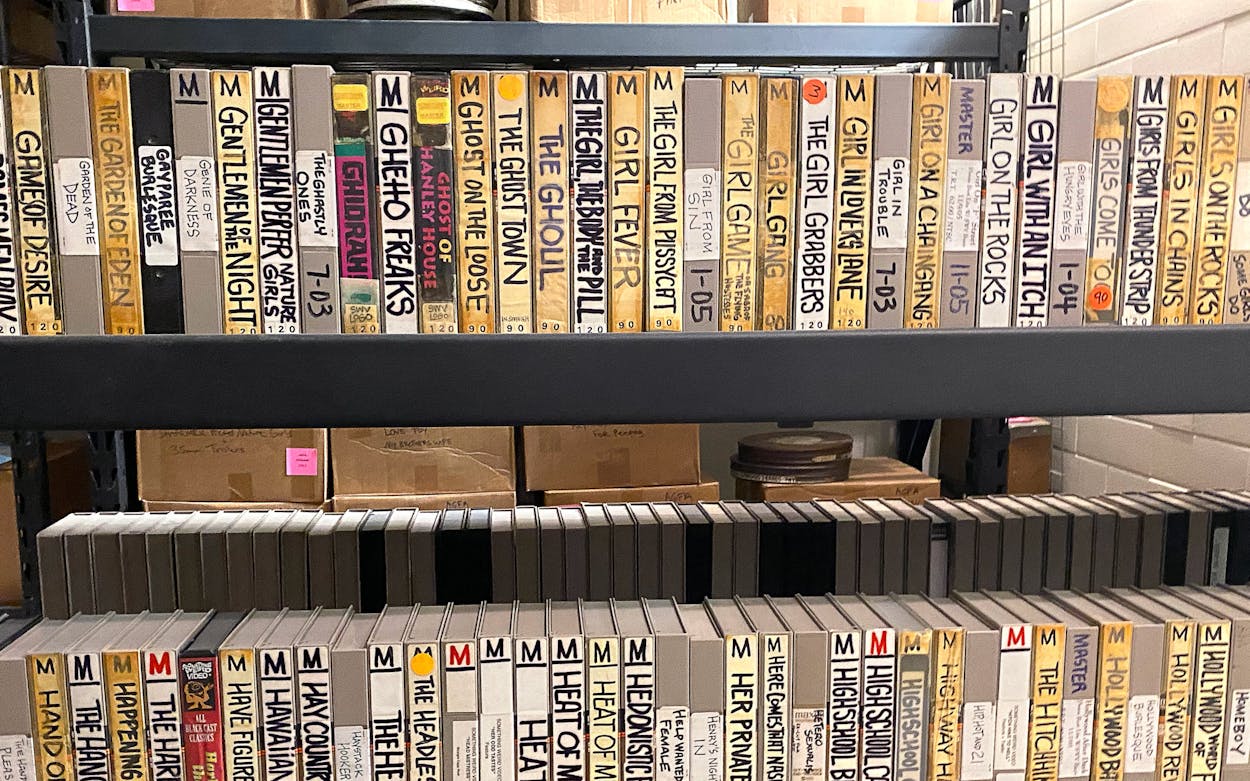

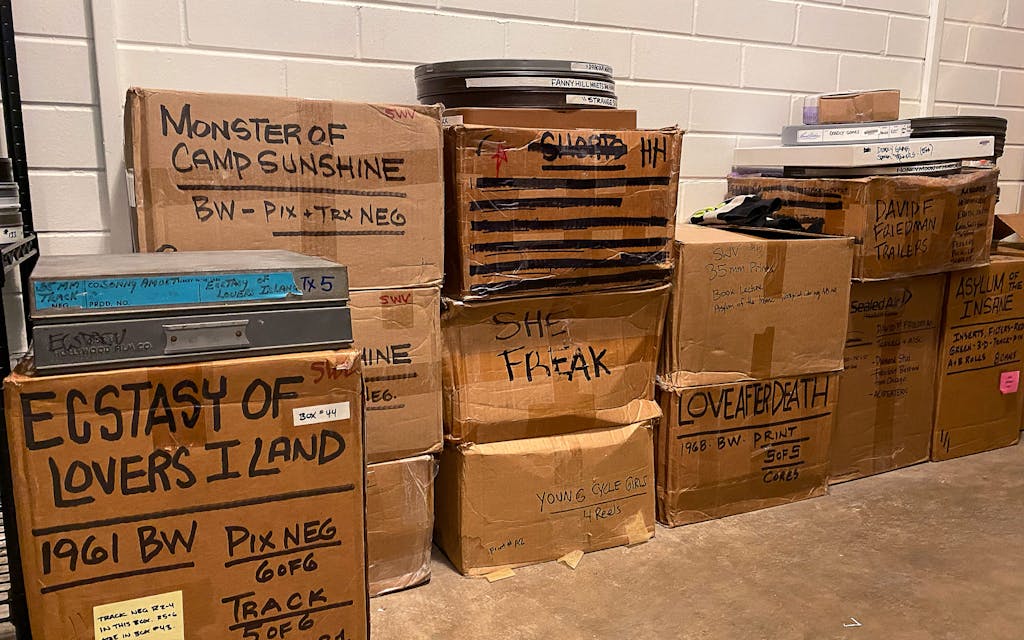

While the AGFA’s film collection is currently scattered throughout the Alamo’s various Austin locations, the heart of it lies inside the old Baker School in Austin’s Hyde Park neighborhood, where the Alamo Drafthouse established its new headquarters in November 2019. The building still looks very much like a school on the inside, right down to the rows of metal lockers that (thankfully) were long ago scraped of their lead paint. “You can still feel the bullying,” Nilsen jokes as he and League take me down hallways lined with colorful one-sheets from the Alamo’s collectibles arm, Mondo, and past former classrooms stuffed with a century’s worth of movie arcana. We pop into one that houses long file drawers along each wall, all of them filled with around four thousand movie posters. Some of these may one day end up adorning the dozens of Alamo Drafthouse locations that dot the country; some are here just because League can’t stop collecting them. He’s got a thing, specifically, for large-format French and Italian posters from the fifties, sixties, and seventies, but some of his tastes also run a bit more . . . singular. “We have every Don Knotts poster ever made,” League says, not a little boastfully.

Another room is stacked, floor to ceiling, with cardboard boxes loaded with vintage letterpress plates, the kind once used by newspapers to create movie ads. AGFA has around 60,000 of them, League says, a comprehensive collection dating from 1930 all the way to 1982. Some of these will eventually be displayed at the Alamo’s latest expansion, The Press Room bar inside its Lower Manhattan location, where patrons can create their own limited-edition greeting cards or take letterpress classes. Not far away, the backstage area of the school’s auditorium has been repurposed as storage space for yet more boxes, these packed with the DVDs and videotapes that comprise the entire catalog of the recently shuttered Vulcan Video. League has a plan for them as well: the Alamo will soon open a video store, Video Vortex, inside its Austin South Lamar location that will rent the movies for free. But for now—like the letterpress plates, the posters, or the wall that’s filled with nothing but vintage VHS tape labels—these things are simply here, just the latest outgrowth of the original hoarding that spurred the archive’s creation.

When League first began collecting, he’d simply stash those 35mm film prints inside the Drafthouse theaters, cramming in the heavy reels to the point where they actually started buckling the foundation. “[Alamo Drafthouse] Village had a situation where the projectors started hitting the screens too low, and we were like, what the f— is causing that?” League laughs. To illustrate just how much strain the prints were causing, Nilsen says, the Alamo’s facilities director Daniel Osborne sent out a stern email saying that they were storing the equivalent of “twenty-seven Buicks.” They needed to find somewhere else to put this stuff, Osborne said, and soon.

In 2007, with the Alamo’s original downtown location at 409 Colorado threatened by rising rent costs, the Leagues launched a nonprofit, Heroes of the Alamo, in the hopes of saving it. Like most attempts to preserve “old Austin,” this proved to be quixotic; the Colorado location closed and the Alamo flagship moved to the Ritz theater on Sixth Street. Still, they were able to put the donations they’d received toward another cause that was close to the Alamo community’s heart: preserving the theater’s growing film collection. The nonprofit became the American Genre Film Archive; today there’s no telling just how many fleets of luxury sedans could be filled with the things it’s acquired.

AGFA estimates that it currently houses around six thousand 35mm film prints alone. Most of these will eventually pass through what is arguably the most important (if least visually impressive) room in the entire Baker School building, where a 4K scanner is used to make Digital Cinema Packages out of every print in the AGFA library. Many of these are then loaned out for free—“no rights given or implied,” League emphasizes—but programmers can also pay to formally book titles from the six-hundred-plus films in AGFA’s theatrical catalog for which the organization maintains exhibition rights on behalf of scores of independent distributors and individual filmmakers. If anyone in the world wants to show Don Coscarelli’s dreamy horror classic Phantasm, for example, they come to AGFA. Meanwhile, some of the rarest of the rare find their way onto DVD, through AGFA’s own home video label. Under the guidance of AGFA director Joe Ziemba and theatrical sales director Bret Berg, what was once just League’s personal collection has become a genuine cultural force, ensuring these films live on to be discovered by new audiences. It’s the original mission of Weird Wednesday, infinitely expanded.

Of course, one of the perverse appeals of Weird Wednesday was about watching something die. Not just some doomed coed who’d wandered off alone into the woods; often you were watching as the film print itself visibly wheezed its last. A lot of these movies were faded pink and full of perforations. They’d suddenly snap or shred themselves in the projector. Sometimes they’d even catch fire. (“It’s both sad and unexplainably delightful when a film burns, just a gorgeous fireworks moment,” Nilsen says wistfully.) Those that hadn’t been properly stored were felled by what collectors call “vinegar syndrome,” in which the prints actually dissolve into bubbles of acetic acid.

To 35mm purists like League and Nilsen, this is all part of film’s allure; weary, road-damaged prints are full of life and history. League also firmly believes that digital copies are more fragile than film prints—more prone to suddenly being glitched out of existence. Still, the fact remains that these are physical objects in an increasingly cloud-based world. AGFA deals primarily in relics, the fossils left behind by newspapers, video stores, repertory cinemas, and other dead or dying industries.

Even the Alamo Drafthouse itself has recently been threatened with extinction—not just by an endless stream of on-demand content, but by a pandemic that made leaving the couch seem not just inconvenient but dangerous. The Alamo survived, but just barely: after declaring bankruptcy in March 2021, then shuttering a few underperforming theaters (including the Ritz location), then furloughing or laying off scores of employees, it moved tentatively back out of bankruptcy over the summer, reemerging with some new private-equity owners and a cautious optimism that things might soon return to status quo. But even as it welcomes the return of moviegoers, there remains a slight skepticism about whether the kinds of events and signature series that are closest to the Alamo’s soul—the more communal, more experimental experiences like Weird Wednesday—can endure in an era of social isolation.

Unsurprisingly, League and Nilsen both hate this topic.

“We spend too much time humoring people who say s— like ‘the theatrical experience is over,’ ” Nilsen says. “How would you feel about somebody who says, ‘Hey, a bunch of friends are in town, you wanna go to this tiki bar that just opened?’ And they were like, ‘Nah, I could just buy a bottle of booze and sit at home and drink it myself.’ Would you think, wow, you’re really onto something? No, you’d be like, you pathetic loser. Why are we listening to people who say this stuff? Go have your awful future.”

It’s October 6, the end of a roughly nineteen-month hiatus, when Weird Wednesday finally makes its return to the Alamo Drafthouse South Lamar. The show starts at 9:30 p.m., well shy of the midnight hour, inside a theater with plush stadium seating that couldn’t be further removed from the groaning floorboards of 409 Colorado. The room is maybe three-quarters full, with no angry drunks in sight. But while there’s not quite the raucous hum of the old days, friends still call out to friends across the rows. The buzz feels muted, tempered by face masks and a year and a half of fear; the question of whether this is all “too soon” hangs over everything. But although reigning Weird Wednesday host Laird Jimenez begins by recounting the entire history of Weird Wednesday for the audience, starting with Tim League’s expedition to Missouri, we’re not here to dwell on the past. We’re here to “continue this tradition of coming together,” he says, “getting outside the real world and into this weird world where anything can happen.”

Jimenez first assumed control of Weird Wednesdays in January 2014, after Lars Nilsen moved on to a full-time programmer role at the Austin Film Society. As Jimenez notes in his intro, “the world has changed several times” since then—and not just because of COVID or streaming. The audience is different, too, and the series has evolved with it. Tonight’s screening, The Lost & Found Video Night Mixtape, isn’t a movie at all, but an anthology of found-footage clips—celebrity bloopers, cringe-worthy public-access hosts, a babbling David Lee Roth—that have been culled from the early-2000s video compilations that stoned college kids used to kick around. It’s the first entry in an entire month dedicated to straight-to-video releases, featuring movies that debuted in the nineties and as late as the 2010s, many of which never saw their way onto film prints at all. Opening it up to video and digging into more recent movies, as Jimenez tells me later, has allowed Weird Wednesday to bring in greater numbers of international movies, more women directors, more filmmakers of color. And it’s also made it easier to bring in a younger crowd that’s less likely to have the same affection—or patience—for deteriorating 35mm prints or the often-sluggish pace of grind-house fare.

Obviously, cultural attitudes have changed, too. Even toward the end of Nilsen’s run, there was a palpable shift in the reactions toward some of the sleazier sixties and seventies movies, in which racism, misogyny, and rape were commonplace. “I don’t think [today’s] audiences are as interested in the kind of taboo-breaking that seventies exploitation did,” Jimenez says. “There was this ironic detachment—like, a very Gen X thing to say, ‘Ha ha, it’s so awful.’ I don’t think audiences are really doing that now.”

“It’s not as though people going to the Weird Wednesday movies [originally] were approving of those backwards attitudes in the films,” Janisse says. “But I think a lot of people didn’t take it personally. They were able to see it as a piece of its time, and appreciate something about the film, despite it having problematic content. Whereas now I think audiences are more like, ‘Well, why even have the problematic content at all?’ ”

Indeed, even during the Lost & Found screening, there is an uncomfortable silence that greets a montage of professional athletes hugging and kissing, scored with schmaltzy romantic music. The next morning, a commenter on the Alamo’s official Instagram account calls the scene “homophobic,” saying it should have been left on the cutting room floor. “I think this is a generation that feels that it’s time to notice this stuff and correct that stuff,” Nilsen says. “And I don’t think they’re wrong.”

After all, the Alamo Drafthouse itself went through a similar reckoning in the last few years, after several former employees and longtime customers accused its management, including League, of minimizing reports of sexual harassment and assault. In response, League issued a public apology, embarked on a “listening tour” of all Drafthouse locations, and instituted organizational changes aimed at improving the Alamo Drafthouse’s overall company culture, including shaking up its board of directors and stepping down as CEO. Meanwhile, the push to erase the stigma of being just a boys’ club has been reflected in Jimenez’s more inclusive approach to Weird Wednesday.

“Alamo has not had the best track record for being thought of as anything but a place for, primarily, white men, and that’s something we’ve been trying to fight against,” Jimenez says. “A lot of my invitations to people to come [guest] host are to people who don’t look like me or think like me. I’ve tried to make it a more diverse space for programming; bring in other people’s perspectives.”

As the chilly response to that Lost & Found montage illustrates, these are thorny times to navigate for a series like Weird Wednesday, which was always defined largely by its willingness to push boundaries—and even risk upsetting people. But that’s where the importance of having a strong curatorial voice like Jimenez’s comes in. Compared to Nilsen and his huge personality, Jimenez comes off as markedly more shy and self-effacing. Yet he’s equally passionate about the ability of Weird Wednesday and AGFA to foster a durable appreciation for bizarro works of art.

“I don’t know if the movies will be pills you take—maybe it’s a psychedelic experience,” Jimenez says. “But yeah, I hope twenty years from now there’s somebody looking back and saying, ‘Here’s the movies you may have missed that are real mindblowers, that we should be coming and enjoying together.’ I don’t see any reason why that should go away.”

Besides, as Warped and Faded attests, Weird Wednesday was never just about the host, or even just about the movies—many of which (let’s face it) probably deserved to stay forgotten. It was always about the shared experience, and the thrill of seeing something that you never knew existed. The Alamo series may have moved away from some of its own tropes, and begun thinking outside its own limitations of format or genre. AGFA, in turn, may have broadened its mission to include preserving VHS tapes and Don Knotts posters. Yet throughout it all, that same authorial intent remains: to seek out the odd, idiosyncratic voices that make art—and life—a lot more interesting.

“It’s this spirit of discovery that’s still there,” League says. “It’s still about flipping over rocks to find beautiful s—.” Someone’s “beautiful” might be someone else’s trash. But you’ll never know until you look.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Books

- Movies

- Alamo Drafthouse

- Austin