ON CHRISTMAS DAY, DISNEY’S THE ALAMO, Hollywood’s latest historical hurrah, was supposed to gallop into theaters everywhere. Now the studio has postponed the movie’s opening, and what its reception will be is anybody’s guess. Back in the fall of 2001, when patriotic emotions were at a fever pitch, the Alamo seemed to have something to say to contemporary Americans. But two and a half years is a long time in the national zeitgeist, and whether audiences today will want to watch Americans under siege is an open question. Disney, of course, is hoping for another Pearl Harbor, an extravaganza of patriotic treacle that raked in the bucks.

Why did Hollywood decide to remember the Alamo again in the first place? The story begins with Leslie Bohem, the author of such high-minded scripts as A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child and Dante’s Peak. At the Austin Film Festival seven years ago, Bohem had a conversation with screenwriter Randall Wallace (Braveheart). Wallace had driven down to San Antonio to take a look at the Alamo, and when he said he wasn’t going to do anything with the story, Bohem decided that he would and set to work on a script. In 1998 Touchstone Pictures, a subsidiary of Disney, and director Ron Howard became interested in the project and bought Bohem’s screenplay, which Howard would eventually hire John Sayles to rewrite. An auteur of some distinction, who had written and directed Lone Star, one of the more interesting of recent Texas films, Sayles came up with a lengthy script that, depending on whom you talk to, was either brilliant or unfilmable (recent press releases have dropped Sayles’s name from the list of credits). After Sayles, Stephen Gaghan (hot off a best-screenplay Oscar for Traffic) was hired to do another rewrite. Meanwhile, the project languished. What moved it onto the fast track was the attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. As Disney’s chairman, Michael Eisner, explained, the film would “capture the post-September 11 surge in patriotism.”

In the beginning, Howard wanted to shoot the movie in the style of Sam Peckinpah, the Goya of westerns, whose bloody masterpiece, The Wild Bunch, set the gold standard for last-ditch heroics. But to emulate Peckinpah, Howard figured he would need an R rating and about $130 million.

Differences between Howard and Disney soon surfaced. Disney balked at the cost, the violence, and the R rating and went ahead with new plans. The studio changed the target audience to the tamer PG-13 crowd and announced that the budget would be around $75 million. In July 2002 John Lee Hancock, a native Texan, was tapped to rewrite the script and direct a cast that included Billy Bob Thornton as Davy Crockett, Dennis Quaid as Sam Houston, Jason Patric as Jim Bowie, and newcomer Patrick Wilson as William Barret Travis. Hancock, who is 46, had made his mark writing screenplays (A Perfect World, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil) and then, in his directorial debut, helmed The Rookie, a small, family-oriented film that became a surprise hit for Disney last year.

The idea for another Alamo movie was hardly a new one. Stephen Harrigan, whose 2000 novel, The Gates of the Alamo, enjoyed considerable acclaim, says that before September 11, half the directors in Los Angeles had unproduced Alamo scripts in their files. They had grown up on Fess Parker’s Davy Crockett and John Wayne’s World, and they reckoned that someday they just might make that Alamo film. But the fallen towers lent a special urgency to the idea of a movie about Americans taking a stand. It was a time for patriotism. It was a time to spend big money and make a big movie.

All seemed to be going according to plan until Disney’s October 28 bombshell: In its wonderfully kitschy parlance, the Hollywood trade paper Variety announced that “Mouse pushes Alamo to spring”—till April, to be precise, too late for the Academy awards, perhaps too late for everything. Although March 6, the day the Alamo entered into history, would have made sense, apparently the filmmakers needed more time. Maybe the Disney honchos will peg it for April 21—San Jacinto Day. Of course, few in modern Texas could say whether that was the day Buddy Holly died, a new Nordstrom opened, or Sam Houston whupped Santa Anna. Meanwhile, the movie’s price tag—which current estimates put at $90 million—is about to get higher if the rumors are true that some of the battle footage is going to be reshot, at a cost of $1 million. (Make that $5 million, at least.) It’s been months now since shooting stopped and everybody went home. What’s the condition of the Dripping Springs set? Have termites attacked it the way they did the real Alamo last May? Have they marched north and stormed the walls? And what about the meticulously researched Mexican uniforms? Where are they? And where are the Slim-Fast Mexican Americans needed to fill them? (During the original casting call, the first assistant director was dismayed at the bulk of the would-be Mexican soldiers.)

Right now Disney is exactly like the Alamo. A small band of brave, misunderstood defenders is holed up trying to figure out how to wage a successful publicity campaign and overcome the doubts of all those outside the walls. Early skirmishes have not, apparently, gone well. The movie was cut from five hours to three, which is an acceptable length to exhibit to the test audiences who rate these suckers. According to the Austin American-Statesman, The Alamo received “mixed to negative” responses. Viewers complained about the acting, the script, and the battle scenes. Dennis Quaid was said to be “just pathetic.” One plot detail that bothered everybody seems to derive from Giant, another big Texas movie. At the end of that film, racial harmony is symbolized in a closing shot of two babies, one brown, one white, side by side in a playpen. In The Alamo there is a closing shot of two soldiers, one brown, one white, both dying. That scene, rumor has it, won’t be coming to a theater near you.

Now we are in the press-release phase, otherwise called damage control. Director Hancock is, like Travis, sending messages to the world. In a statement from Touchstone Pictures, he had this to say: “The Alamo has, from a very early age, been the most important story of my life, so when I agreed to rewrite and direct the film, I set the bar very high, both for myself and the finished product.” In sum, as I write this, Disney cannot yet hang a banner proclaiming Mission Accomplished, and it looks like a long, hard slog ahead.

HOLLYWOOD HAS ALWAYS LUSTED AFTER historical movies, the bigger the better. In 1915 D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a groundbreaking cinematic epic, dramatized history for mass audiences and thrilled viewers nationwide; President Woodrow Wilson, who sponsored a screening in the White House, is reputed to have said, “It is like writing history with lightning.” Ever since then, that’s the way many Americans have preferred their history: in the dark instead of on the page.

The Alamo attracted filmmakers from the beginning. The Immortal Alamo was shot on location in San Antonio in 1911, and in 1915 Martyrs of the Alamo, heavily influenced by The Birth of a Nation, told the familiar story in similarly broad racist rhetoric. When Martyrs was rereleased in the twenties, it bore a different title, The Birth of Texas. Clearly, the early historical epics were about nation-building. North of 36 and The Covered Wagon, also in the twenties, extended the form westward. The Civil War and the West seemed to provide the best material for such nationalistic sagas; witness Gone With the Wind and Red River—in one, nostalgia for chattel, in the other, for cattle.

But the Alamo continued to have new claimants. In Heroes of the Alamo (1936), the brave defenders sang a version of “The Yellow Rose of Texas” the night before the final assault, although the song was not written until 1858. The fifties saw three Alamo movies. In The Man From the Alamo, Glenn Ford played Moses Rose, the man some believe was the only defender to leave the Alamo after Travis drew the line in the sand. Disney’s Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier nailed the coonskin cap to everybody’s barn door, and The Last Command was a stodgy oater featuring a wooden Sterling Hayden as Jim Bowie.

Of course, the biggest Alamo movie of all was John Wayne’s, released in 1960. Although Wayne’s publicity machine cranked out story after story about how authentic The Alamo was going to be, moviegoers and critics had a field day spotting errors—the old mission is located alongside the Rio Grande instead of the San Antonio River; Goliad is said to be north of San Antonio instead of southeast—and historians have been able to find little that is accurate in it. But according to the Duke, his version made plenty of sense: “I think it’s the greatest piece of folklore ever brought down through history,” he said at the time, “and folklore has always been the most successful medium for motion pictures.”

By simultaneously ducking the question of historical accuracy and offering a brilliant explanation of the difference between history and film, Wayne pointed to the essential dilemma of anybody seeking to tell the absolute truth about the Alamo: No one knows what really happened. The truth is always changing, as new scholarship and new documents and new interpretations challenge the old, received ideas, many of them burned permanently into the collective American consciousness by powerful celluloid images. There is a whole body of Alamo scholarship that is constantly being roiled by new books, and there is a whole body of scholarship about the Alamo movies themselves. Anybody trying to sort out fact from fiction has his work cut out for him. But there are plenty of Texas males (women, on the whole, have not written much about the Alamo, but that may be changing) who visited the Alamo when they were in short pants, never fully recovered from the experience, and have gone on to become Texas historians, pouring out a seemingly endless drip-drip-drip of books and articles on this peskiest of all Texas stories.

FROM THE BEGINNING, JOHN LEE HANCOCK felt the hot breath of Texas patriots on the back of his neck. He was very much aware of the controversial reception a poorly researched Alamo movie would likely get in Texas—or a well-researched one, for that matter. When I spoke with him in October, as we both thought he was putting the finishing touches on the film, he talked about the problem: “I think that when you’re doing something like this, when it’s a story as important as this is to me, anyway, you’re always going to feel the burden of history.”

Hancock sees the mythic tale as a “character drama”—it’s both a “big story and a small story at the same time,” he said—and has sought to open up the narrative, to explain how the men, especially the major figures, came to be at the old mission. In his telling, Texas offered them a second chance. Travis fled debts and a wife and child; Bowie had a decidedly unsavory background as a slave trader and frontier brawler; and Crockett wanted a fresh start in a place far from Washington, D.C. The Alamo gave them all a shot at redemption, though they would have much preferred to walk away from it victorious to fight another day. And unlike most Alamo films, Hancock’s doesn’t end with the fall of the garrison but goes on to dramatize what happened in its aftermath.

The Alamo story has built-in expectations because it has been filmed so many times and has inspired so much commentary. Starting out, Hancock was faced with a mass of material. “Like every other kid in Texas, I took Texas history and knew all of that,” he told me, “but there had been so much written in the last thirty years that I hadn’t read, and catching up on that, I said, ‘I’m just gonna find the most interesting stories.’” The reading continued right through the making of the film, and by the end, the production-office crew had assembled a small library of Alamo volumes, some 21 titles in all, ranging from Walter Lord’s A Time to Stand to Jack Jackson’s comic-book format The Alamo: An Epic Told From Both Sides.

Faced with so many conflicting versions and arguments, Hancock adopted a clever strategy to ward off the accuracy police: He enlisted the help of historians more fully than any previous director of the Alamo story ever had, embedding them in the day-to-day work of making the film. Their purpose was to help him get the facts right and, one has to believe, to preempt and defuse criticism from historians such as themselves.

He called upon Jesús F. de la Teja (A Revolution Remembered: The Memoirs and Selected Correspondence of Juan N. Seguin) and Andrés Tijerina (Tejano Empire: Life on the South Texas Ranchos) to review the script to verify the Mexican perspective and Stephen Hardin (Texian Iliad) and Alan Huffines (Blood of Noble Men: The Alamo Siege and Battle) to be on the set every day of shooting. As Huffines told the Austin American-Statesman, “We sit behind John Lee and look at what the camera sees and try to find mistakes.” Of course, Hancock said, “There’s always going to be those moments when they point out, ‘Gosh, that guy has the wrong shoes on,’ and you tell them, ‘Well, he’s about a thousand people back, and no one will ever see that.’” And sometimes the historians had to suspend their allegiance to literalism. The decision to film the Battle of San Jacinto at the Lost Pines Nature Ranch, near Bastrop, prompted Hardin to observe, “Does it look exactly like San Jacinto? No. San Jacinto is a swamp. We have all this dust here, but it looks great on-screen.”

The striving for historical accuracy extended to the kinds of details that few viewers would be able to distinguish, like the uniforms worn by the Mexican army, which are said to be correct down to the last button, and the linguistic variations among the soldiers and officers. Hancock sought the expertise of Arnoldo Vento, a professor of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Texas at Austin, to get it right because, explained Hancock, “It’s not just period Spanish; it’s the caste system being in place, several different types of Spanish being spoken,” and he brought in a “Cherokee specialist to monitor our Cherokee.” All of the non-English dialogue will be rendered in subtitles for those of us who aren’t up to speed on Spanish and Cherokee.

One of the things that just about everybody can agree on is that the set, built on the Reimer Ranch, near Dripping Springs, is the most authentic Alamo set ever constructed. Designer Michael Corenblith, another Texan who visited the Alamo as a child, oversaw the construction of the mission and its environs. On a site covering 51 acres, the set is reputed to be the largest ever built in the U.S. (Alamo films, like the state, thrive on superlatives.) Harrigan, among others, has praised Corenblith’s scrupulous devotion to detail, telling the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “The set is, almost brick for brick, San Antonio de Béxar in 1836.” It won admiration from all who saw it, including Frank Thompson, an author of several books on Alamo lore, who rhapsodized to the Dallas Morning News, “I think we all want to be able to visit it once a year for the rest of our lives.” (Among Alamaniacs, such enthusiasm is not uncommon.)

I asked Hancock about the mise-en-scène of his film, the particular style and look that he has given the story. “I call it Dirty Dickens,” he said. What this means, along with the dust and grime, is a lot of shaggy facial hair in the form of period muttonchops. “People think of it as a western, for some reason,” Hancock went on, “which is beyond me, since it happened in 1836.” He said that when folks tell him they’re “dying to see a western, lots of cowboys,” he replies, “We got some top hats but no Stetsons; they’re not invented yet.” I raised the question of firepower. Repeating pistols and rifles would certainly make for a lot more bang-bang, but of course they hadn’t been invented yet either. “You got the old black powder and a few percussion rifles,” Hancock noted, “but you’re pretty much slow-loadin’.” I was reminded of Michael Lind’s long poem, The Alamo: An Epic, in which he inexplicably gives Travis a “Colt revolver,” which Travis certainly could have used but which did not yet exist.

The question of armaments is not an idle one. American films like Braveheart and Gladiator, which Hancock admires, did an impressive job of bringing to life battle scenes that could easily have looked phony and unconvincing. For the battles in The Alamo, Hancock and his cinematographer, Dean Semler (who won an Academy award for Dances With Wolves), were inspired by the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa and the “operatic quality of large armies moving” in his classic films like Seven Samurai and, especially, Ran. Hancock wanted the battle scenes to feel operatic, he said, rather than doing them with “a whole lot of quick-cutty, inserty-type stuff” (i.e., like Peckinpah). It took more than a month to film the last assault. Hancock wanted to show the way the battle played out, not as one overwhelming charge by the Mexican soldiers but as a series of assaults on first one wall, then another. No previous Alamo movie has been able to translate the battle carnage into either cinematic opera or kinetic butchery, and it must be one or the other. The final assault cannot have the bloodless feel of a reenactment. Of course, it will take place in the pre-dawn dark. Historically accurate, yes. Cinematically powerful? We shall see.

THE NARRATIVE OF THE ALAMO presents some difficult, if not intractable, problems. It’s a siege story, and it has to generate a sense of intense psychological pressure, sort of like a submarine saga in which everybody is confined within a small, cramped space. In other words, a male-bonding-through-violence movie—Black Hawk Down on the ground or, again, The Wild Bunch. And the emotion, the visceral excitement, must come from action, not speeches. In the great walk to their final Götterdämmerung in Peckinpah’s film, William Holden says only, “Let’s go,” and the men gather their weapons and stride into the arena of their deaths. It’s one of the most profoundly moving tracking shots in the history of cinema.

The other big narrative problem with the Alamo, especially for a modern popcorn crowd, is the lack of a love story. Ain’t no women of any interest at all attached to the Alamo. Nor in the films mentioned above, of course, but again, those are works of great kinetic energy and, in the case of The Wild Bunch, a kind of liberating beauty.

A director of an Alamo film also has to make some hard choices. I asked Hancock about three tough ones: what he did with the line in the sand, the yellow Rose of Texas (Moses, not the song), and the death of Davy Crockett. “How do I answer this and still be smart,” he said, laughing. “I don’t have Rose in it. And I don’t have Travis drawing the line.” Travis’s character development, Hancock explained, grows out of the film’s letting him “become his own kind of man and a hero and a leader and has little to do with the heroic gesture.”

And then there is the question of Crockett’s demise. Everybody has a stake in how Davy (he actually preferred David) expired; it’s easily the most debated and most controversial element of the Alamo story. Hancock does not much want to talk about it, partly, it seems, in order to not give anything away. “When you talk about the line in the sand and Crockett’s execution,” he said, “I guess the best answer would be, I know those are hot-button issues and I hope that people come to the theater to see for themselves.” But his use of the word “execution” definitely seems to give something away. Indeed, in the copy of the script I obtained, which is dated January 27, 2002 (the film was not available for me to see), the death is staged as depicted in Mexican officer José Enrique de la Peña’s controversial book, With Santa Anna in Texas, which was published in English in 1975 and which some experts consider to be either a forgery or of dubious veracity. According to de la Peña, Crockett and a handful of other defenders surrendered, only to be executed on direct orders from Santa Anna.

This scene brings together two of the story’s major characters, Santa Anna (played by Emilio Echevarria) and Crockett. Often portrayed as a total tyrant, Santa Anna is in Hancock’s script more complex, though no less brutal. “If you’re going to have an antagonist like Santa Anna, it’s not very interesting if he just stomps around and plays dictator,” Hancock told me. “That’s kind of more cartoonish. I needed to understand politically what was going on, and the more I read about the coterie of generals around him, the more fascinating the whole Texas campaign became from the Mexican side.” Hancock uses one of these generals, Manuel Castrillón, to “ask the hard questions of Santa Anna” so that the dictator won’t come off as “just a one-note, kill-‘em-all” monster.

Crockett’s brief confrontation with Santa Anna reveals his self-awareness—the knowledge that he is in many respects a prisoner of his own fame, that history is in fact forcing him to become the legend depicted in The Lion of the West, a popular play of the time, and in the Crockett almanacs, which recounted his exploits, both real and imagined. In Thomas Ricks Lindley’s new book, Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions, Crockett’s standing at the time of the siege is memorably caught in a letter from John S. Brooks, a young Virginian attached to Colonel James W. Fannin’s command at Goliad, to his mother. Relaying recent news from Béxar regarding the Alamo defenders’ successful repulsion of attacks, Brooks wrote, “Probably Davy Crockett ‘grinned’ them off.”

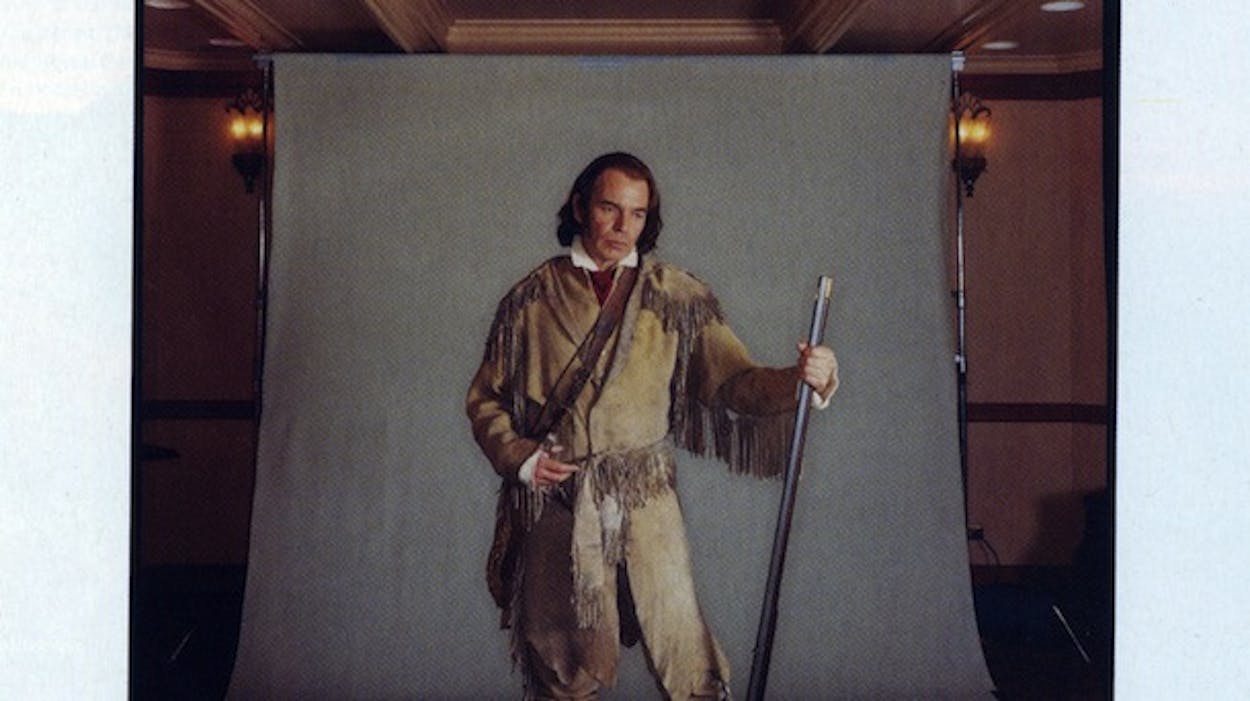

If the script is any guide, Billy Bob Thornton’s Crockett may well turn out to be the film’s dominant figure. The part is extremely well-written, and according to Hancock, Thornton was “just fantastic.” Between takes, “he would be talking to the different extras and the defenders, and you’d see him over there with twenty-five people, telling stories, and everybody laughing.” Hancock told me that at one point, when Thornton was cutting up, he walked over to him and said, “You know, you’re our Crockett. You keep the men amused while we’re doing hard work,” whereupon Thornton looked at him and winked. “He looks like him too,” Hancock added. “Look at the paintings of Crockett.” Hancock has spoken often of the crucial spirit and élan that Thornton brought to his portrayal, telling one interviewer, “I just didn’t know anybody else who could play the role, quite frankly. If Billy hadn’t agreed to do the movie, I probably wouldn’t have done the movie.”

EVEN BEFORE THE CURRENT FIRESTORM, Hancock recognized the pitfalls of trying to lasso the biggest sacred cow in Texas. For one thing, he knew that, in some quarters, “if you’re making a movie about the Alamo, then it’s a racist movie.” To this charge, he responded, “We tried to make it as historically correct and dramatically correct as we could. Our actors from Mexico and Spain certainly felt that it was more than fair, and I was happy to hear that.” But, he conceded, “Everybody is going to have their ax to grind, and I know I’m right in the crosshairs.” In the end, it will matter less whether a Mexican soldier’s uniform is 100 percent accurate than whether the emotion of the assault on the fortress will stir the audience. “I’m trying to please that little eight-year-old boy who went to San Antonio and the Alamo the first time,” Hancock told me. “It meant something to him.”

The day after Disney announced that the opening would be postponed, Hancock called me from New York, where he was scoring the movie. He wanted me to know that it was the looming release date, the “time crunch,” that drove the decision to delay the opening. He spoke of the “alchemy” that he’s trying for in order to get six major characters properly balanced in the telling of the tale. “I care more about the movie,” he said, “than when it opens.” He wants to get it right, and he thinks he’s close. “Ten years from now, I’ll be in a hotel room flicking the channels and the movie will come on, and I don’t want to look at it and see something and think, ‘Gee, there’s a bad decision I made because I rushed it.’”

Buzz and anti-buzz (the sound of a bee dying, a movie imploding) will doubtless continue right up to that day in April when we’ll find out whether Disney’s coalition of the willing has achieved a mission statement to remember.

- More About:

- Film & TV