One warm spring day in the late nineties, I walked hand in hand with my father as he led our family—my mom, my three siblings, and me—into Houston’s Jones Hall for an Alvin Ailey performance. At eight years old, I was more excited to be wearing my new theater dress for all of Houston to see than I was for the show itself. But that excitement quickly evolved into wonder. I don’t recall the name of the performance we saw, but I distinctly remember feeling admiration and reverence for what the dancers were doing in front of me.

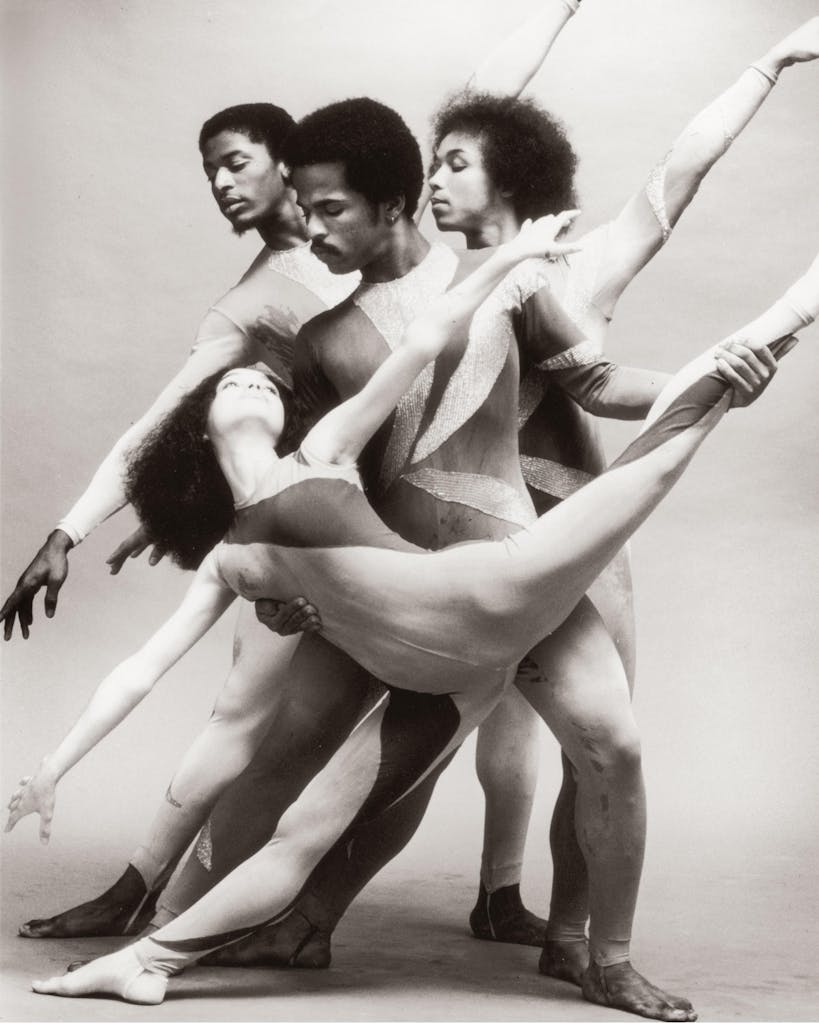

Before that day, I’d never seen such a large group of professional Black dancers on stage. Experiencing this performance in my youth was significant; it told me that my people were everywhere, and capable of doing everything. Years later, in 2019, a close friend invited me to an Ailey performance at NYU’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts. Tracks, a dance set against a backdrop of brilliantly selected O’Jays, Pharrell, and Snoop Dogg tracks, reminded me of seeing that first Ailey show in childhood, and of the incredible movement and possibility of the freed Black body.

As I made the difficult decision this past spring to remain in New York City to avoid potentially affecting my parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, I desperately sought out anything that connected me with home in Houston. Near the start of lockdown, though, a friend sent me a link to performances that became available to watch online during the pandemic (thanks to the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which carries on the dancer’s legacy beyond his 1989 death). Among these was Revelations, inarguably Ailey’s most famed work. Spiritual, painful, and redeeming, the performance bewitched me: at once, I felt the love of culture, the sorrow of oppression, and the memories of generational pain.

I knew this piece had to be based on Ailey’s upbringing in Texas, and I’d found what I needed to get through this moment. His works are at once a source of pride, provide a moment of reflection, and are a potent testament to the power of Blackness. As a longtime reveler in Ailey’s work, this time spent in quarantine has allowed me to view his choreography through a different lens: one of a migrating Texan trying to find her way in the world with Blackness in tow.

As a gay and HIV-positive man who was private about his personal life, Ailey communicated both his emotions and history through dance: he worked to integrate the dance industry and create stories that reflected Black pain and triumph, and was ultimately awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. While Alvin Ailey spent most of his career working in New York City’s midtown, the roots of his practice began in Rogers, Texas, where he was born in 1931. In his book Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture, Duke University professor of dance Thomas F. DeFrantz details how Ailey grew up amid three forces that shaped his life: the Black church, an era of painful segregation, and the poverty of rural Texas during the Great Depression. “I heard about lynchings,” Ailey says in an interview DeFrantz included in the book. “Having that kind of experience as a child left a feeling of rage in me that I think pervades my work.”

As he progressed in his career, Ailey’s rage grew in tandem with deepening racial divisions in Texas, becoming part of what dance scholars have described as “blood memories.” He translated some of these wrenching memories into dance pieces that spanned the diversity of Black experience, from Blues Suite—a flirtatious ode to the jubilant and sensual behavior that occurs on Saturday nights before Sunday churchgoing—to the beloved and harrowing Revelations, a meditation on Black grief and joy. “The Black pieces we do that come from blues, spirituals and gospels are part of what I am,” Ailey once said in an interview. “They are as honest and truthful as we can make them. I’m interested in putting something on stage that will have a very wide appeal without being condescending; that will reach an audience and make it part of the dance; that will get everybody into the theater. If it’s art and entertainment—thank God, that’s what I want to be.”

Revelations has three sections: “Pilgrim of Sorrow,” “Take Me to the Water,” and “Move, Members, Move.” In Pilgrim of Sorrow, dancers don tan clothing and move to three solemn spirituals; for the second section, blue and purple ribbons stream across the stage against a blue backdrop, as performers dance to “Wade in the Water.” Finally, “Move, Members, Move” sees dancers triumphantly moving to church music in their Sunday finest—a stunning finish true to the choreographer’s Baptist roots. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s associate artistic director and dancer Matthew Rushing believes all three sections are especially meaningful in this current moment in which Black Americans across the country are fighting for equality and racial justice. “We’ve identified the problem, but how do we cleanse the things we’ve been used to and complicit with?” he says. “And finally, how do we move on? This is where we get to perseverance and victory with the African American heritage.”

Revelations is potent even behind my laptop or my TV screen. In a taped performance from 2016, Black dancers glided across the stage with seemingly effortless grace. During the “Wade in the Water” scene—and ode to one of the most prominent songs in Southern Baptist culture—Ailey’s choreography evokes both a spiritual and an emotional experience that I’ve felt only in Black churches, at Black community events, and with my family.

The late dancer knew that African American culture was complex, describing it as “sometimes sorrowful, sometimes jubilant, but always hopeful.” Amid ongoing protests and a spike in coronaviruses cases, anxiety and fear cast a shadow over Black life, but I’ve found comfort and hope in Black community and artistic traditions. For Ailey it was the church and juke joints. For me, it’s waiting for new Ailey performances to be released every few weeks on the Ailey All Access YouTube channel. Leaning into their current mission of “Still We Dance,” a commitment to continue dancing even during socially distant times, the company has included behind the scenes footage of performances, and viewers can connect and learn moves with the dancers on Instagram while gaining a deeper understanding of how the productions happen.

The company also recently streamed jazz musician Donald Byrd’s Greenwood. This piece, which references the Tulsa race massacre, a 1921 tragedy that happened in what was then one of the nation’s most-affluent African American communities, known as “Black Wall Street,” is part of their intention to showcase performances that speak to our moment in history. Currently, it is rebroadcasting Rennie Harris’s Lazarus, an ode to the biblical story and to Alvin Ailey’s life that also comments on racial inequities.

Rushing and his team hope that people watching these Alvin Ailey performances feel a sense of pride from home, and that they are reminded of the brilliance—and the legendary dancer and choreographer from Texas—behind the works. “No matter how many times we’ve been knocked down, or anything that’s come against us as a people, there’s always this, this endurance and perseverance that we possess,” says Rushing. “You can always turn sorrow into joy, and that’s what we’ve been known for.”

- More About:

- Pandemic

- Black Lives Matter