This whole American Dirt controversy has been awful. The harder people try to extricate themselves, the deeper they sink. Writers are finding themselves arguing with friends and heroes. We’re looking at our colleagues and marveling at their cluelessness, and we’re getting in lots of social media fights.

Sure, some people have insisted that we look on the bright side: at least we’re talking about books, right? At least we’ve got people discussing the migrant experience, no?

Well, Luis Alberto Urrea’s The House of Broken Angels is a best-seller again, partly due to the many articles offering lists of books about the borderlands that are better than American Dirt. Coffee House Press is scrambling to print new copies of Myriam Gurba’s Chicana memoir Mean. And American Dirt’s publisher has agreed to hire and publish more Latinos. But if a mess like this is what caused those things to happen, then clearly the publishing industry still has a long way to go.

Let me take a step back for those of you lucky enough to have missed the drama.

Jeanine Cummins, a woman of Irish descent with a Puerto Rican grandmother, spent a few years researching and writing American Dirt, a novel about Lydia Quixano Peréz, an upper-class Mexican woman, and her son, Luca, who join a migrant caravan heading toward el Norte after a cartel kills Lydia’s husband and their entire family. Cummins received a rare seven-figure advance for the book from her publisher, Flatiron (an imprint of Macmillan), and she sold the film rights immediately.

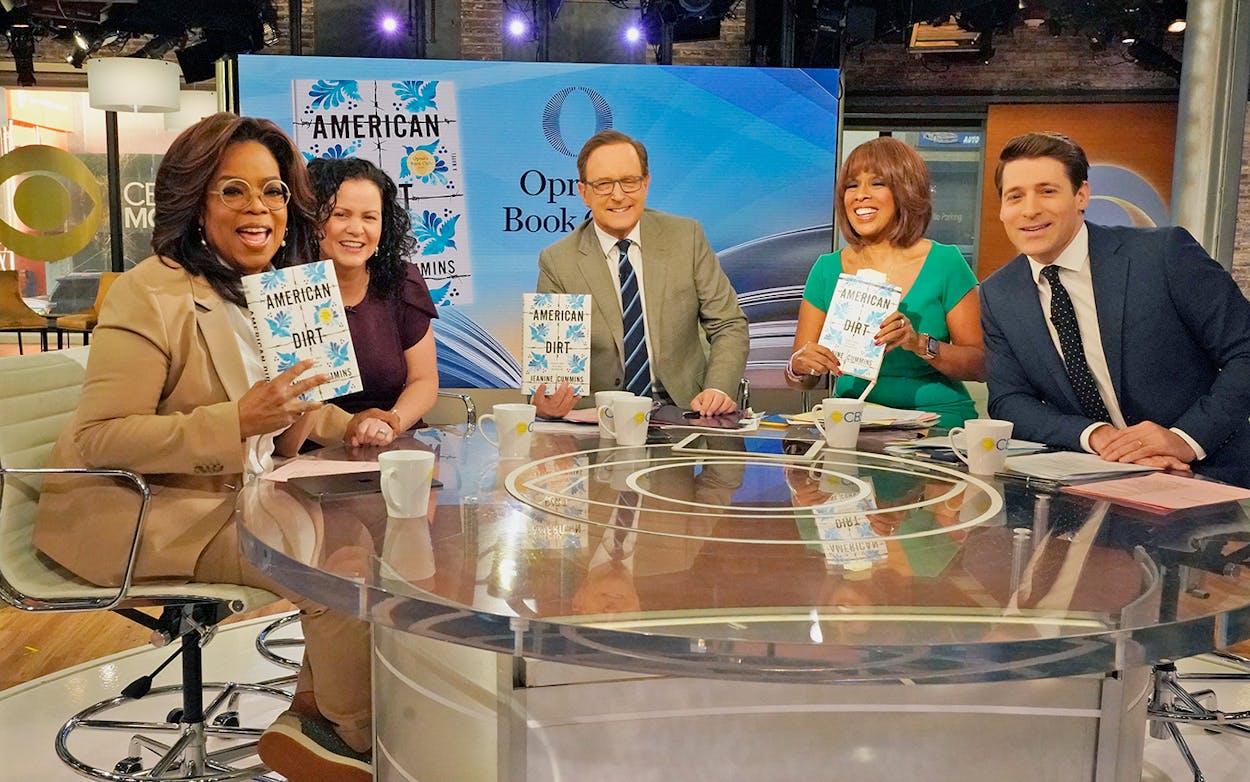

The early buzz was deafening. Booksellers quickly latched onto American Dirt, making it their number one recommended book for February. The novel received starred advance reviews in Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly and hefty blurbs from literary heavyweights such as Sandra Cisneros, Reyna Grande, Julia Alvarez, Don Winslow, and Stephen King. Upon publication, it drew raves from big media entities: NPR, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times—name a national outlet and it probably gave American Dirt a stellar review. The book, with no small boost from Oprah’s Book Club, was presented as a game changer: a novel about the immigrant experience that was compassionate and gripping, and would open people’s eyes to a suffering that so many Americans cannot begin to comprehend.

There were, though, stirrings of dissent. Last December, Myriam Gurba wrote a blistering piece on the website Tropics of Meta detailing how Ms. Magazine killed her fiercely negative review of the novel. Gurba’s critique—equally brilliant, vulgar, and vicious—pointed out multiple inaccuracies in the novel’s depiction of Mexico and explained how it reinforces some of the most harmful stereotypes about Mexico and immigrants. Then, Parul Sehgal in the New York Times tore the book apart for simply being bad. “The real failures of the book,” she wrote, “have little to do with the writer’s identity and everything to do with her abilities as a novelist.”

More and more Latinx writers started to question why the publishing industry was so eager to anoint Cummins’s book as the savior of our fractured era. Esmeralda Bermudez, in the Los Angeles Times, asked why this novel garnered so much attention and money when so many Latinx writers had been writing better books about the border and immigration for years? What about Urrea (whose work was a clear, maybe too clear, influence on American Dirt)? Why not Valeria Luiselli or Marcelo Hernandez Castillo? Or any of the other countless writers of color who have been told over the years that no one wants to read about Mexicans?

There were other missteps by Cummins and her publisher, everything from her bending the truth about her “undocumented” Irish husband to the gobsmackingly stupid decision to set out barbed-wire themed centerpieces at a luncheon celebrating the book. In other words, Cummins and Flatiron have a lot to be criticized for and both have acknowledged as much.

Yet, as often happens in our online culture, this argument was quickly flattened and distorted. The most reductive and harmful summary of the numerous critiques of American Dirt is that her detractors are asserting that Cummins’s whiteness should preclude her from writing about people of color. But while there are a few people out there claiming that authors should never write outside of their lived experiences, they’re mostly a fringe group. To the book’s most cogent critics it doesn’t matter at all that Cummins is white.

Instead, Gurba and other Latinx writers are frustrated that American Dirt, despite its cultural inaccuracies and stereotypes, is being presented as a book—no, the book—that will force people to recognize the injustices being done to Latinx people on the border and well beyond.

In her much-discussed author’s note, Cummins admits her didactic intentions. She writes about how President Trump’s 2016 election—and the ugly anti-immigrant rhetoric that both preceded it and has since followed—was one of the impulses that pushed her to finish the novel.

“I was appalled at the way Latino migrants … were characterized within that public discourse,” she wrote. “At worst, we perceive them as an invading mob of resource-draining criminals, and, at best, a sort of helpless, impoverished, faceless brown mass, clamoring for help at our doorsteps. We seldom think of them as our fellow human beings. People with the agency to make their own decisions, people who can contribute to their own bright future, and to ours, as so many generations of oft-reviled immigrants have done before them.”

These are, obviously, good intentions. And those good intentions are written all over each page—to the point of acting as a constant distraction. American Dirt’s Mexican characters are in awe of how beautiful Mexican cities are, at how nice so many migrants are, at how everyone has such sad stories, at how many people in Mexico really are people after all. The detective who’s not on the cartel payroll stiltedly says, “I know how it must look, every murder going unsolved, but there are people who still care, who are horrified by this violence.” Eight-year-old Luca pauses in his grief to admire the “cartoon colors of his city.” The coyote who takes Lydia and Luca across the border has a little backstory that shows his heart of gold. Characters info-dump how the asylum process works. And on and on.

The book goes out of its way to explain Mexico and Mexicans, largely because Cummins is writing through a lens that could not be less Mexican. Not because she’s white but because the readership she has imagined for the book—that problematic “we” that “seldom thinks of [Mexicans] as our fellow human beings”—isn’t just white. To her mind it’s ignorant, and needs to be spoon-fed one-dimensional characters in order to believe that migrants are three-dimensional people.

Personally, I’m very far removed from any sort of immigrant experience. Though I’m a Latino with brown skin and a new daughter with a Spanish last name as her first name, my ancestors have been in New Mexico and South Texas for centuries. The last time my family crossed a desert was four hundred years ago, when we were running from the Spanish Inquisition. So I’m not really part of the group that Cummins is writing about. But I’m not part of her “we” either.

I don’t need a book to help me realize that the undocumented students at the high school where I teach have agency. I don’t need a book to open my eyes to the people who need help. My eyes have been open my whole life and American Dirt was simply not written for me.

Which is precisely the problem.

This scandal is a story of open-minded, progressive people full of good intentions getting swept away by a flood of hype. Don Winslow compared American Dirt to The Grapes of Wrath. Julia Alvarez said the book can “change hearts and transform policies.” Stephen King said, “This book will be an important voice in the discussion about immigration.” Kirkus Reviews, which I frequently write for, said the novel “makes migrants seeking to cross the southern U.S. border indelibly individual.” NPR said the novel “nails what it’s like to live in this age of anxiety.”

Review after review looked past the book’s odd POV shifts, frequent malapropisms, and anthropology-textbook prose in order to promote its supposed ability to reach white readers. In a recent Latino USA episode on the controversy, Sandra Cisneros admitted that Cummins’s name on the book jacket would reach an audience that Cisneros’s own name just couldn’t.

All of these people, not to mention Cummins herself, genuinely want the world to be a better, more tolerant place. And to make that happen, they all promoted a book that they thought would sway some mythical white person: their racist uncle, a bigoted grandmother, a swing voter in Florida who voted for Obama in ’08 but switched to Trump in ’16. American Dirt was written for and marketed to those theoretical people—virtually none of whom are ever going to read it. And those few who do aren’t going to look toward the southern border and solemnly remove their MAGA caps just because they read a mediocre thriller. They’re not going to call out their racist coworker because a white author has made the apparently novel case that Mexicans are people too.

I’m a novelist myself, but I don’t believe that novels can do what so many people were desperate for this one to do. Yes, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle actually had an effect on American attitudes toward slavery and the food industry. But both of those books came out more than a century ago, well before radio, television, film, and the internet stole primacy from the printed word. We simply don’t live in a society any more in which novels change the world. Yes, literature can change lives, open hearts, expand minds—trust me, I know. But very few of the people who would read Cummins’s book are the people she’s trying to reach—much as I have a pretty good sense of who’s going to read this article and who’s going to read the responses that blame the whole mess on “PC culture run amok.”

The publishing industry, egged on by an inflated sense of its own importance, acted as if this middling genre book would spark that most elusive of all things, “a national conversation,” and instead alienated a massive segment of its consumer base. If American Dirt, million-dollar advance and all, had been billed as a juicy romance or a narco-thriller, there still would have been plenty of complaints. But they would have died down in a day or two, and we wouldn’t still be fighting about it.

One place where this fight won’t continue is at your local bookstore or literary festival. Last week, Flatiron canceled Cummins’s book tour, citing unspecified “threats of specific physical violence.”

“Unspecified” seems to be the operative word here. Flatiron offered no details, and earlier this week journalist Roberto Lovato said on Twitter that the publisher has acknowledged that Cummins hadn’t received any death threats. (By contrast, Myriam Gurba has received death threats for her criticisms of American Dirt.) There may be some ambiguity here—perhaps Cummins received threats that weren’t specifically death threats; perhaps some bookstores were informed that they would be subject to disruptions. But given how vague Flatiron has been about this, you can’t help but notice that calling the tour off has allowed Cummins to dodge uncomfortable questions from aggrieved readers.

And you certainly can’t help but notice that all this loose talk about undefined threats of violence allowed Flatiron to take control of the situation. Weeks of Latinx writers carving their ideas into the discourse got wiped away in a second. White writers suddenly felt a need to write op-eds stating that violence is bad. What a bold claim and a brave stand. Violence = bad? Who knew? Stephen King pompously tweeted: “We don’t threaten writers with violence. Not in America.” Twitter users quickly called out King’s remark as being woefully out of touch with the everyday threats of violence directed against women and writers of color.

If American Dirt was written for a white audience, then who are these anti-violence messages meant for? Which segment of the culture do these white writers think need to hear this message? Hint: it’s the very readers American Dirt didn’t feel obliged to address.

And that’s why so many of us are upset about this book. We’re not jealous of the money. We’re not demanding our own million-dollar book deals as acts of literary reparations. We don’t want Cummins marched through the streets of the barrio while we throw stale conchas at her. We want stories about ourselves that aren’t written for someone else. We want to be taken seriously by the major publishers and the media. We want stories about our experiences that aren’t the equivalent of tear-jerking after-school specials.

And make no mistake, despite American Dirt’s clumsy writing, Cummins knows which emotional buttons to push. At the end of the book, when Lydia and Luca are in the desert, exhausted after their ordeal, knowing how close they are to death and how close they are to salvation, I started to feel a tightness in my chest and a tension in my jaw.

But not for Lydia and Luca. I felt anxious for myself and my daughter. Like I said, I have no recent family memory of crossing the border. But that doesn’t mean I don’t think about it all the time. I thought about it before the 2016 election and I’ve thought about it more ever since. Even the most “assimilated” Latinos stop and wonder if their time here, in the country we helped build, is limited. Reading American Dirt, I couldn’t help but think about going on the run with my infant daughter. Retracing the steps my ancestors made but in reverse—on the run not from cartels but from my own government.

In order to write this piece I read the book that wasn’t meant for me and, through sheer exploitative force of brutal emotion, I saw myself in it. But the industry gatekeepers who promoted American Dirt didn’t think about recent immigrants, or second-generation Americans, or fifteenth-generation Americans. They didn’t think about us at all.

At the end of the day, the publishing industry turned us—my us, not Jeanine Cummins’s us—into the faceless brown masses that it so desperately wanted to humanize.

Austin writer Richard Z. Santos’s debut novel, Trust Me, will be published by Arte Público Press on March 31.

- More About:

- Books