He sat down on the porch and started to type on the small glass screen of the device that they still called a phone when they sold it to him. His fingers barely moved but he felt the excitement he’d feel if he had just faced down a swarm of raiders in stinking rags that had once been clothing in a world that was lost to time, sitting under a waning gibbous moon while his wife waited indoors, eager for him to return from whatever foolhardy errand he had set himself upon on that infernal device. Honey, she said. Come back to bed and stop all of that. He sat still and ignored her, his eyes on the stars, thinking about the glory that was to come. I’ll be there in a minute, he said.

What are you doing.

I’m writing a tweet from the perspective of literary legend Cormac McCarthy, he said. I created a fake account under his name. I’m tweeting as though I’m him, to make a joke about engagement metrics and the vapidness of social media by expressing the contempt that I’m certain the author of The Road and Blood Meridian would feel toward the external pressures to produce content on such platforms.

That doesn’t sound like a good use of your time, she said. Time was short since the baby was born. She knew the child, small and helpless as a newborn foal, would be awake in a few hours and it was his responsibility to care for the youngling this night. What satisfaction derived from falsifying a Twitter account from one of the great living writers, the pride of El Paso, could outweigh a few precious hours of sleep before the nightly cycle of broken rest, a child’s cries, and a day of work began. She asked him, where is the drama in pretending to be Cormac McCarthy? You used to be an artist, she said.

Oh, I’ve got it figured out. Cormac McCarthy is tweeting because his publicist, Terry, is forcing him to do so. He cares not for the pretensions of this world he has found himself living in, nearly nine decades after his birth. The tension of the storytelling comes from Cormac’s struggle to remain true to himself, in the face of the unrelenting pressures of the contemporary world.

So it’s a humorous anachronism, she said.

I’d like to think so.

But why Cormac McCarthy, she said. Your tone and style don’t even really attempt to match his. It’s easy enough to imitate his authorial voice. I don’t understand the joke. It would be the same joke if you pretended to be Bob Dylan or Daniel Day-Lewis. The joke is just that he’s old and generally more sophisticated than the people who spend their time on Twitter. No one will believe it.

That’s where you’re wrong, he said. And he pushed send.

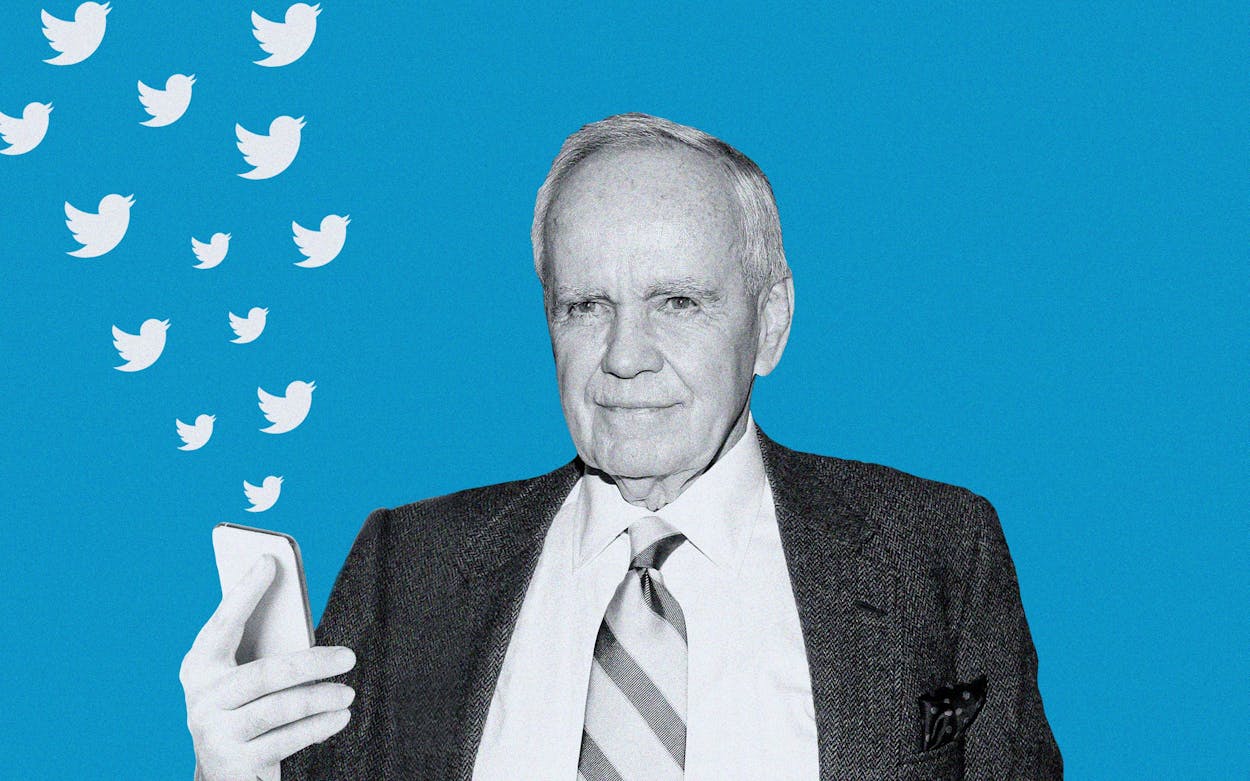

Thank you for reading our little dramatized version of what led to a dumb viral moment from over the weekend, when a clearly fabricated tweet, purported to have been posted by Cormac McCarthy, somehow went viral. The tweet is fake, according to a representative from Knopf, McCarthy’s publisher, who responded to Texas Monthly’s query with great alacrity, presumably because he has been receiving similar messages all morning. Cormac McCarthy is not on Twitter. He has never been on Twitter, despite a similar hoax in 2013. Regardless of what online pranksters have said in the past, the 88-year-old author of The Road and All The Pretty Horses, who spent two decades in El Paso, is still alive—he just doesn’t tweet.

So why did the tweet go viral? @CormacMcCrthy has been posting since 2018, but this appears to be its first time getting much traction. Maybe this latest joke was especially witty, or, more likely, it filled the void of a slow news day on Twitter. While this account had some obvious clues—Cormac McCarthy knows how to spell his own name, for one; for another, there’s the gag that McCarthy, who has not published a novel since 2006 and currently has nothing to promote, is subject to the pressures of a junior publicist—people want to believe what they want to believe. Other famous authors responded to the account as though it were real, so maybe that’s why it took off? Stephen King tweeted a response to it, and if Stephen King thinks it’s real, who are we to be cynics?

Adding to the confusion, the account was verified by Twitter sometime between Sunday night and Monday morning—apparently indicating that the account really and truly did belong to Cormac McCarthy. (As the Verge reported, the verification was quickly yanked.) Why did the prankster get the blue check mark if he or she could not furnish convincing proof of identity? Again, who can say! Paula Vogel, the winner of the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play How I Learned to Drive, is unverified on the service, despite multiple attempts to prove her identity. Why does she fail to meet the verification guidelines, while some rando pretending to be Cormac McCarthy does not? That’s a question for Twitter, which at press time had not responded to a request for more information. In response to Texas Monthly’s request for an interview with the user behind the account, @CormacMcCrthy wrote, “There’s no limit to what a man can do or where he can go if he doesn’t mind who gets the credit,” which doesn’t clear much up.

There are a few conclusions one can draw from the whole silly affair: One, that Twitter’s verification process is weird and arbitrary, but also that it carries an uncommon amount of weight for no good reason. Two, that even internet users who are sophisticated enough to enjoy the work of one of America’s most esteemed literary figures are susceptible to obvious hoaxes, if they’d prefer to believe them to be true. And three, if Cormac McCarthy ever does decide that joining Twitter would be a good use of his time, the site’s users are extremely ready to read whatever nonsense happens to be on his mind.

- More About:

- Cormac McCarthy