“And the Grammy goes to . . . Black Radio, Robert Glasper Experiment.”

Those words, uttered last February at the fifty-fifth annual Grammy Awards ceremony, may have caught you by surprise—even if your name was Robert Glasper. The Houston-born-and-raised jazz pianist had just won the award for Best R&B Album, upsetting a field that included R. Kelly, one of the genre’s biggest stars, and Anthony Hamilton, one of its most admired. “It was surreal,” recalls Don Was, the president of Glasper’s label, Blue Note Records. “I didn’t think he had a chance in the world.”

At the time, that sentiment was probably shared by the members of the Robert Glasper Experiment, seated so far back in the auditorium of Los Angeles’ Staples Center that the camera operator had to swoop around to find them. It took the band a full minute to reach the stage, at which point Glasper was still in shock. “Thank you for allowing us to play real music,” he said from the podium, “and to play what we really feel from our heart.”

Black Radio, released early last year, was Glasper’s attempt to synthesize the full range of music he’d been involved with over the years: state-of-the-art acoustic jazz, underground hip-hop, and organic R&B. The album featured an array of guest vocalists—such as neo-soul priestess Erykah Badu and rapper Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def)—backed by the Experiment, a band with a coolly beguiling skill set. Because Glasper had made four previous albums in a more straightforward jazz vein, Black Radio was hailed as a crossover effort, and the album’s domestic sales figures—93,000 and counting, according to Nielsen SoundScan—support that idea. (A typical jazz release on Blue Note, the most prominent label in the genre, sells only a few thousand copies.)

Black Radio was a true hybrid, and it confirmed that the Experiment now defines the vanguard of a movement in contemporary black music. Other parties have picked up the thread, like NEXT Collective, a young jazz band featuring two more Houston natives, which made a splash this year by covering Jay-Z and Kanye West, and Glas-per’s bassist Derrick Hodge, whose recent Blue Note debut thoughtfully blends jazz with gospel, funk, folk rock, and sound-track pop.

This month Glasper and his crew are aligning behind Black Radio 2, which involves another elite assemblage of talent, including the rappers Snoop Dogg and Common and the singers Norah Jones, Brandy, and Jill Scott. But where Black Radio featured a lot of hazily reframed cover tunes, the new album consists almost entirely of originals. “I didn’t want to make the same album twice, just with different guests,” Glasper explains. “I wanted this one to sound different.”

The 35-year-old pianist is sitting in a restaurant near his apartment in downtown Brooklyn, wearing several layers of black and trying to ignore the symptoms of a stomach bug. A natural extrovert with strong opinions, he projects the casual self-assurance of an artist with nothing to prove. “He’s a commanding presence,” says Was, who before heading up Blue Note produced albums by the likes of Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones. “He could run for office if he wanted to change careers.”

Not much chance of that, though, given how music-obsessed Glasper has been from the start. Raised by his mother, a professional singer, he spent his early childhood tagging along on her nightclub gigs around Houston. He cut his teeth playing in church and enrolled in the city’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, which had already turned out a succession of free-thinking jazz virtuosos like pianist Jason Moran and become a major feeder to the elite jazz colleges in the Northeast. “We have more cats on the scene than anybody,” Glasper says proudly.

As a student he drew inspiration from Moran’s recent example, even as he was shaped by the ambition of his classmates—including one Beyoncé Knowles—and the guidance of Robert Morgan, the school’s trailblazing director of jazz studies.

“Houston didn’t have a jazz scene,” Glasper recalls. “The jazz scene was literally in our high school. Mostly I was playing gospel; Houston’s huuuuuge for gospel music. I’d play at three churches when I was in high school: a Seventh-day Adventist on Saturday, a Catholic church early Sunday morning, and then a Baptist church at eleven o’clock on Sunday.” At one service he played with two HSPVA classmates: drummer Kendrick Scott, now an accomplished bandleader, and Mark Kelley, now the bassist in the Roots. “So once or twice a week after school, we would pack up in my car and go to choir rehearsal. But we would put all this jazz stuff in the church music, mixing it up just for fun.”

That dual experience—playing each weekend for spirit-filled congregations and then returning to the jazz laboratory on Monday—goes a long way toward explaining Glasper’s MO. He’s nothing if not outspoken about jazz’s failure to reach a broader public: last year DownBeat magazine ran a cover story titled “Slap: Robert Glasper’s Jazz Wake-up Call.” One central problem, as he sees it, is that jazz musicians have started playing more for one another than for the lay listener, boosting the music’s complex obscurities at the expense of clarity and emotion. Yet he takes pride in refraining from pandering, and he certainly has jazz-level chops.

After accepting a full scholarship to the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music, Glasper made a quick impression on the ground in New York. Then his self-produced debut album, Mood, caught the ear of an executive at Blue Note, and he became the first newly discovered jazz artist to sign to the label in years (since Moran, in fact). He recorded two acoustic jazz albums on Blue Note, but at the same time he was also expanding into other corners of black music. Though he had never warmed to the woozy, boast-filled style of Houston hip-hop artists like Chamillionaire or DJ Screw, he connected with a different side of rap music in New York. “I got into hip-hop just being in Brooklyn, hanging out,” he says. Badu happened to live down the street, and soon he was working steadily with rapper Q-Tip, formerly of A Tribe Called Quest, and spending time in the studio with J Dilla, the late producer whose shrewd, elliptical beats dictated the pulse of the movement called neo-soul.

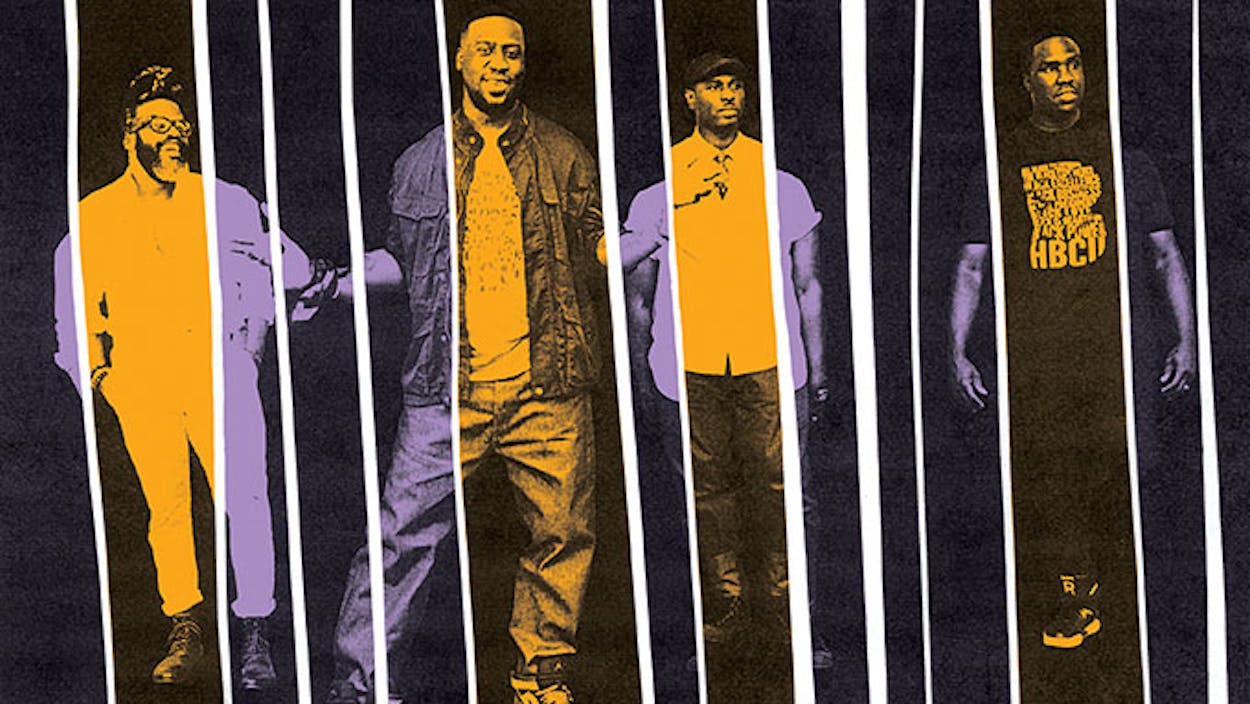

Out of all this activity came the Robert Glasper Experiment, which made its first appearance on record with 2009’s Double Booked. Along with Glasper and Hodge, it featured saxophonist Casey Benjamin, who doubles on vocoder, and drummer Chris Dave, another high-impact HSPVA alum. (Dave has since left to focus on his own groove-minded band, the Drumhedz, which will release an album on Blue Note next year; his replacement is Mark Colenburg.) The band’s style-blending openness quickly endeared it to a range of artists in the bohemian sector of hip-hop and R&B.

“Each member of that band has his own voice and something creative to offer, not just in one genre,” attests Common. “They can go play any type of music and make it beautiful.”

For the moment, though, Glasper is intent on delving deep into one particular type of music. “It’s a straight-up R&B album,” he says of Black Radio 2. “This is not even really the ‘jazz meets whatever’ record. Once we won the Grammy, I had to think different, because now we’re on the radar for all the R&B people.”

He considers the album not only a commercial opportunity but also a chance to push against the grain of contemporary black pop. “A lot of people are making great music, but it’s all underground,” he says, attacking the “cookie cutter” output shaped by an array of corporate interests he calls “the machine.” The Black Radio series is his attempt to swing for the fences while refusing to play the game.

“Nobody’s doing what we do,” he says. But when the Experiment does master classes at colleges, he encounters students striving to emulate the band’s style. It’s probably too much to hope that Black Radio will shift the status quo, but it just might produce a new class of talented musicians devoted to “playing for a feeling,” to borrow Glasper’s phrase.

“Jazz cats used to be the ones who got called for Marvin Gaye or Aretha Franklin sessions back in the day,” he says. “Now the whole thought of a jazz musician is that it’s not soulful anymore. I want to kill that. I want people to aspire to do what we’re doing.”

Nate Chinen is a music critic for the New York Times and a columnist for JazzTimes.