Over 27 days in March and April, Reginald Adams and his team of five artists transformed a previously nondescript gray wall in downtown Galveston. Using boom lifts and more than three hundred gallons of paint, the group that calls itself the Creatives set up camp in an empty parking lot. As he painted, Adams passed the time with reggae music thumping in his ears. Curious tourists and locals walking by often stopped to watch and talk with the artists, who explained the significance of the spot where the Old Galveston Square building now stands, surrounded by gift shops. Here, on June 19, 1865—two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation—is where a Union general read the declaration that finally let enslaved Texans know they were free. Now, as the Juneteenth holiday rises to greater national prominence, a five-thousand-square-foot mural titled Absolute Equality makes this vital and long-overlooked moment in Texas history impossible to ignore. Adams says it’s about time.

“The history of Juneteenth has always been there since the moment General Granger and those soldiers occupied Galveston,” Adams says, noting that a historical marker was installed on the site in 2014. “But it took the artwork to put a face on that history, an identity that now creates entirely new conversations, entirely new curiosity around what happened on that date.”

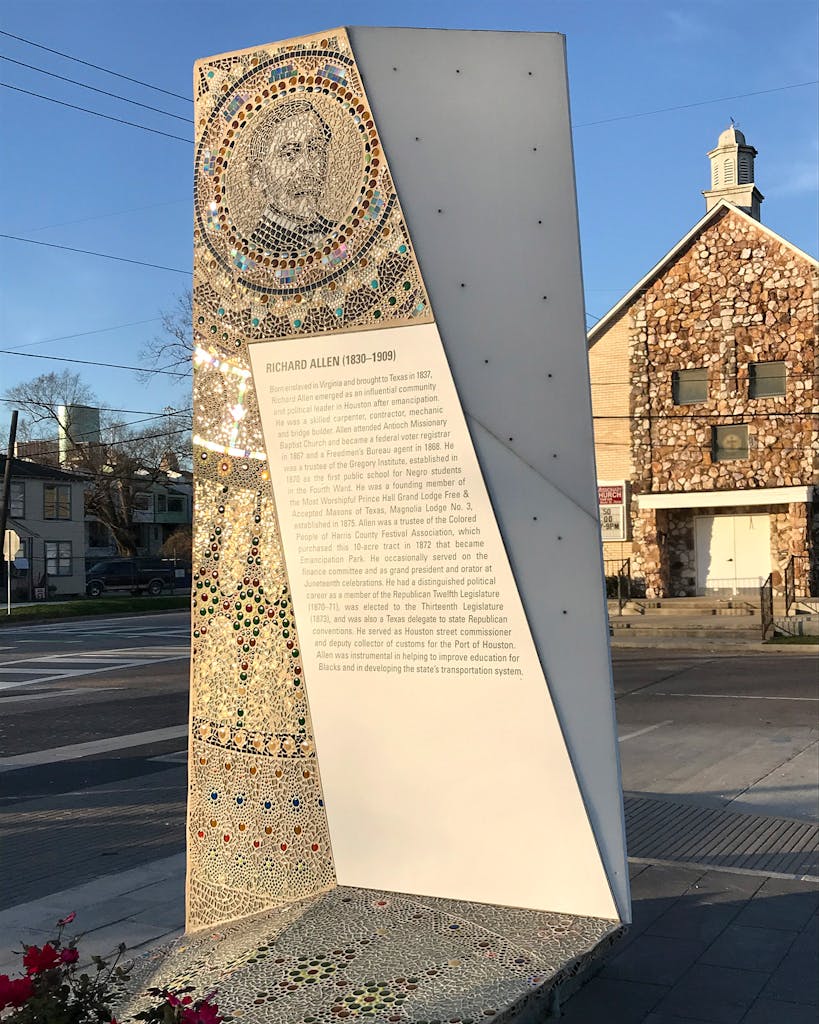

For Adams, 48, the mural is a highlight of his nearly thirty-year career as a public artist focused on Black culture and history in Texas. His bold, vibrant mosaics, sculptures, and murals can be found across Houston—from Elements of Change, a series of four glass and ceramic mosaics honoring the founders of Emancipation Park, to I Can’t Breathe, a captivating close-up portrait of George Floyd painted outside the Breakfast Klub diner in Floyd’s old neighborhood, the Third Ward. Adams has also made art at schools, community centers, government buildings, health clinics, and dozens of other public places around Houston and the state. He’s drawn to public art in part because he’s an extrovert who enjoys collaborating with community members and civic leaders. More important, he admires the way a mural on a restaurant or a sculpture in a park can make art accessible.

“Most of the kids in our inner city don’t visit traditional art spaces. They don’t go to the Museum of Fine Arts. They aren’t going to go to the Contemporary Arts Museum,” he says. “I saw public art as a clear, easy, accessible path to bringing art for [those] who would never otherwise maybe have access.”

His path to becoming a professional artist was an unconventional one. Adams, who was born in Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1972, moved around a lot as a child because of his father’s job as a soil scientist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. To deal with being the new kid in class, he used art as a way to bond with his classmates. The adults around him weren’t always supportive, though: he recalls a painful moment in kindergarten, when his teacher humiliated him after he didn’t follow instructions in an activity meant to teach colors and shapes.

“I remember her grabbing my paper. [She] picks it up, lifts it above her head, and draws the class’s attention to my work,” he says. “She then commences to tearing my paper in half. Then she takes my crayons and she crushes them into a thousand little pieces.”

The moment was defining for Adams, causing him to steer clear of any art classes as a child. But he also says it didn’t deter him—instead, it solidified his identity an artist.

“I knew then, even at the tender age of five, that this is me and I’m not what you just did,” he says.

He continued to draw on the walls of his bedroom, mostly characters from his beloved comic books. In 1992, to his father’s ire, Adams dropped out of Texas A&M University after his freshman year. He’d earned a full scholarship and planned to study accounting, but his heart wasn’t in it; he was ready to pursue art full time. He moved in with his mother in Houston and immersed himself in the city’s burgeoning art community. Adams began networking and meeting leaders in the field, including Michelle Barnes, cofounder of the Community Artists’ Collective, and Rick Lowe, founder of Project Row Houses, the nationally recognized program that blends affordable housing and cutting-edge art and design.

Barnes helped Adams land some of his first jobs, teaching art classes at Shape Community Center and at the Community Artists’ Collective. He paid the bills by juggling a range of art-related jobs: painting signs and teaching at after-school programs, among many other gigs. Barnes says Adams’s creative flexibility has served him well.

“He doesn’t try to make something that worked in one project work in another. But he’s learned and grown through those previous experiences, and each new project presents a new challenge,” she says. “There’s no formula to it. He’s just up for the challenge.”

Adams was 21 when he took on his first large-art public project. El Franco Lee, former Harris County commissioner, tasked him and a team of artists (with help from Barnes) with designing a memorial park for congressman Mickey Leland, who died tragically in a plane crash in Ethiopia in 1989.

Each commission led to the next. In 2019, Adams was the lead artist for the $33 million renovation of Emancipation Park, the city’s first public park and a popular gathering place for Juneteenth celebrations. He helped design four mosaic monuments honoring the founders of the park. With more than 800,000 glass tiles in colors representing earth, wind, water, and fire, the statues position the four men who created the park—community leaders and former slaves John Henry “Jack” Yates, Richard Allen, Richard Brock, and Elias Dibble—as elemental to Houston’s history.

About a year ago, Adams started using the title “the Creatives” to refer to the loose collective of artists he partners with. He often collaborates with artists from diverse backgrounds; the team on the Galveston mural included an artist from Nigeria, Sam Abimbola Adenugba, as well as three Houstonians.

Last summer, as the pandemic raged and the death of George Floyd flooded news coverage, the Creatives painted a mural in his memory at the Breakfast Klub, a beloved diner in the Third Ward, Floyd’s old neighborhood. The work was cathartic.

“It was therapy, because I’m angry, I’m frustrated, I’m confused. Like, how are we letting this happen?” Adams says.

After Floyd’s death, as Black Lives Matter protests took place around the country, Juneteenth celebrations also garnered more attention. Black Texans have always celebrated Juneteenth, of course, but now 49 states and the District of Columbia officially recognize the holiday. Samuel Collins III, a Galveston historian who serves on the board for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, thought now was the time to create a larger conversation around Juneteenth in the city where the declaration was issued.

“I believe all of those events unfortunately were like a constant drip on a rock, and this rock burst open,” said Collins. “Now there is a window of opportunity to be more proactive in the work.”

In 2012, Collins raised funds for a historical marker at the site of the former Osterman building, where General Gordon Granger read General Order No. 3 aloud. The marker was erected in 2014, but Collins was disappointed to see that few passersby seemed to notice it on their way to the restaurants and bars in Galveston’s downtown square. A mural would draw more attention, he decided. He quickly secured permission from the building owner, Mitchell Historic Properties.

A young Houston-bred artist named Chayse Sampy drew the first sketch of the mural, and eventually Adams got involved to help. Adams’s design was submitted to the Galveston Landmark Commission for approval. In March, the artists began working on the mural, which shows key figures central to Juneteenth and the racial justice movement: Abraham Lincoln, Harriet Tubman, General Gordon Granger, and the United States Colored Troops. Visitors who download the free Uncover Everything app can scan the mural with their phones to see videos and read more on the history of Juneteenth.

The mural features five round portals (circles are a recurring motif in Adams’s work). The first depicts Esteban, or Estevanico, who is believed to be the first enslaved African to come to North America. He was shipwrecked on the Texas coast with the Spanish Narváez expedition of 1528, and later led more expeditions for Spain. He’s followed on the mural by abolitionist Harriet Tubman, one hand beckoning escaped slaves to follow her on the Underground Railroad, and the other grasping a lantern. In the next section of the mural, Abraham Lincoln, who issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, stands stoically, grasping a chain with open manacles. We also see General Gordon Granger signing General Order No. 3 (whose text is included in full at the bottom of the mural) as the United States Colored Troops look on solemnly. The mural includes an astronaut, symbolizing continued exploration. Finally, there’s a group of people walking forward, marching toward the idea of “absolute equality.”

Adams is finalizing a documentary about Juneteenth and the production of the mural. He and his team are also designing six murals for the Edison Arts Foundation, creating a series of sculptures for a new community park in Houston, and designing artwork and graphics for two floors of a new hospital in San Antonio. But he says he’s especially proud of the Juneteenth mural.

“Part of the journey of what our ancestors died for, was for us, you and I, to be able to do what we’re doing, so that what they did was not in vain,” he says. “It should become a trend. It needs to. Everybody and their mama needs to know what Juneteenth is about.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- Galveston