Julia Sweig’s just-published Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in Plain Sight (Random House) is the most significant biography of the late first lady to appear in more than two decades. For the book and her new ABC News podcast In Plain Sight: Lady Bird Johnson, Sweig, a nonresident senior research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, drew on audio diaries that Lady Bird kept during her White House years. The 123 hours of tape, which had been “hiding in plain sight” for years (a heavily redacted selection was published in 1970 under the title A White House Diary), portray Lady Bird as a far more active and influential participant in the LBJ presidency than most observers have thought. They also offer a vivid and up-close narrative of American political life during the sixties, featuring a cast of characters that includes Martin Luther King Jr., Jacqueline Kennedy, and Richard Nixon.

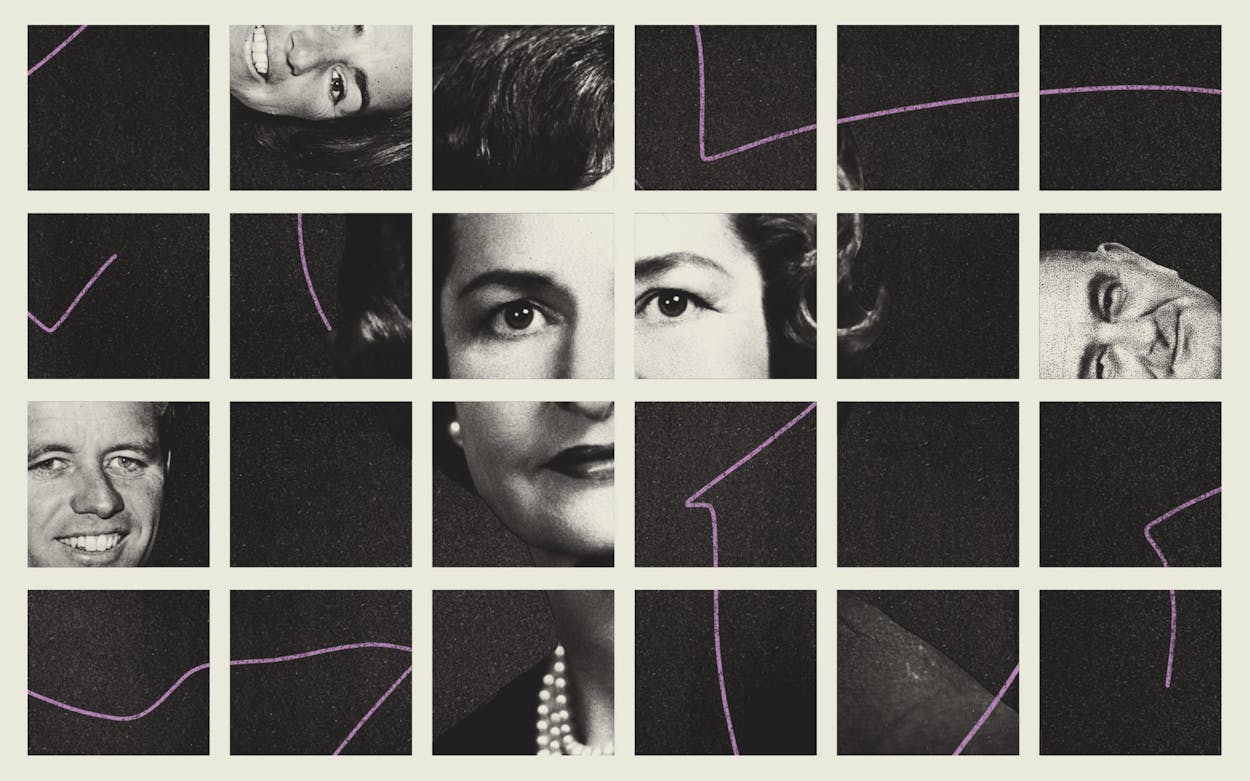

In this excerpt, the first couple attends Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 funeral in New York City. The Johnsons were as shattered as the rest of the country by RFK’s assassination, but their strained relationship with the Kennedy clan made the event a difficult one for them to navigate, as Sweig and Lady Bird make clear.

The morning of Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral, Lyndon and Lady Bird turned to their usual review of newspapers, finding them “drenched with every aspect of the story,” as she recorded in her diary. The relentless media exposure of the violent details of Kennedy’s assassination on June 5, 1968, and the painful displays of family and national mourning had exhausted the country and the Johnsons. It would be a long day: attending the funeral at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, in New York City, receiving the train carrying RFK’s coffin and entourage later that afternoon back in Washington, joining the procession through the capital to the burial site at Arlington Cemetery.

During LBJ’s last trip to St. Patrick’s two months earlier for the ordination of the new archbishop of New York, the crowds had greeted the president with a measure of respect and relief, reassured and impressed by the statesmanship of his withdrawal from the presidential race four days earlier. But the tectonic political and emotional shift of a country wrestling with the assassinations of RFK and Martin Luther King Jr.—a country whose maladies LBJ had come to personify at home and abroad—was now palpable in the crowd inside and outside St. Patrick’s.

On the Saturday morning of June 8, “New York was a strange sight,” Lady Bird recounted. “The streets were lined with people who stood silent, motionless . . . the voiceless chorus” of a Greek tragedy. St. Patrick’s was filled to overflow with four thousand people. Inside, an “absolutely stricken” Pierre Salinger, RFK’s campaign manager, escorted the Johnsons up the nave. They paused briefly as they passed Bobby’s flag-covered coffin, before taking their seats in the front row, on the left side of the aisle.

Just as they moved into their pew, the congregation “silently, and without signal,” rose to its feet. Lady Bird’s predecessor, Jackie Kennedy, “in black and veiled,” had entered, along with John Jr. and Caroline. JFK’s widow and children walked past the Johnsons to take their seats in the front row on the right side of the aisle, the Kennedy family side. Bobby’s widow, Ethel, and her ten children, who ranged in age from one to sixteen, sat to the right. A third widow, Coretta Scott King, sat a few rows back—also, Lady Bird noticed, on the Kennedy family side of the aisle.

Under the cathedral’s vaulted ceilings mourned members of Congress, current and former Kennedy and Johnson cabinet members—the Goldbergs, the McNamaras, the Rusks, the Dillons, the Harrimans—military brass, New York’s scions of philanthropy, and the country’s leading journalists, artists, and intellectuals. The pews were filled with campaign and policy advisers who just two days earlier had imagined themselves staffing an RFK White House, and with the leaders of the new American political coalition RFK had begun to stitch together during the primaries, including activists César Chávez, John Lewis, and Dolores Huerta. Other than George Wallace and Dick Gregory, every 1968 presidential candidate sat among the mourners.

And so, too, did each of Lady Bird’s potential successors: Muriel Humphrey, Abigail McCarthy, Happy Rockefeller, and Pat Nixon. Lady Bird could see Leonard Bernstein only from behind, but as he conducted a painfully beautiful rendition of Mahler’s “Adagietto” from Symphony No. 5, she saw in him “an expression of the utmost of passion, of torment and talent,” words Lady Bird may well have reserved for Bobby himself. In some ways, the gathering felt like a requiem not just for Bobby Kennedy but for the Democratic party—or for the Johnson chapter in American political history.

Senator Ted Kennedy’s “most beautiful eulogy” equally moved the first lady. Well practiced in scrutinizing how public figures delivered their messages and connected with their audiences, Lady Bird captured the moment: “Partway through, his voice began to quiver but then came under control and ended calmly.” Teddy’s eulogy included a composite of a number of speeches his brother had given—in South Africa, in Mississippi. His eyes “red-rimmed,” Teddy “asked that his brother be remembered simply as a good and decent man who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it,” she recorded. Another line of “sheer poetry” from George Bernard Shaw that Bobby had often paraphrased, although the first lady didn’t know its provenance, was also memorable: “Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not.” At that moment, the purity of grief had transcended the resentments that had built up between the Johnsons and the Kennedys over the years.

The president and the first lady were the first to exit the cathedral after the funeral. On their way, they walked over to the Kennedy family. The patriarch, Joseph Patrick Kennedy Sr., who in 1955 had offered to back an LBJ presidential bid if he would make Jack his running mate, had been unable to travel to his son’s funeral, his health severely diminished by a stroke. But LBJ shook hands and spoke briefly with Teddy, and Lady Bird grasped Teddy’s hand too. They stopped to speak with Ethel, Bobby’s greatest advocate and protector, her face “beautiful, sad, composed.”

They spoke to several of her children and also to Rose Kennedy, the matriarch, whom Lady Bird had admired when they first met at the Kennedy family’s Hyannis Port compound in August 1960. During that visit—just after the Democratic convention, when the Johnsons accepted the vice presidency and threw their lot in with the Massachusetts clan—Jack and Jackie had gone out of their way to make the Johnsons comfortable, hiding their own toothbrushes, emptying their drawers, and squeezing into a twin bed in a guest room so the Johnsons could spend the night in their room.

It was also, apparently, when Jackie began to develop her first impression of Lady Bird, whose habit of taking notes whenever her husband spoke reminded Jackie of “a trained hunting dog.” That was a severe misjudgment of Lady Bird’s ability to deploy her 360-degree powers of observation and encyclopedic recall in the service of Lyndon’s and her own sizable ambitions.

It had been almost eight years since that visit, when a pregnant Jackie had asked Lady Bird’s advice on how best to help her husband’s candidacy while sitting on the sidelines, minding her womb. And it had been almost five years since Jackie and Lady Bird navigated, together and separately, the brutal reality of Jack’s assassination and the fourteen excruciating days of transition that followed.

In the early weeks and months after Jackie’s exit from the White House and then her departure from Washington, the Johnsons had stayed in touch with her with letters and with invitations, all declined. They renamed the White House’s redesigned East Garden the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden. Even as Lady Bird finally felt she had gotten out from under Jackie’s shadow, she built on Jackie’s initiative to fill the White House with notable works of art and continued with her historical preservation projects. But there was only so much Lady Bird could do to heal the wounds of November 1963. By June 1968, Jackie had been living on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan for four years and had begun to date Aristotle Onassis, a Greek shipping magnate, far older and shorter than the multilingual equestrian debutante.

After the warm exchange with Ted, Ethel, and Rose, Lady Bird perhaps expected to find a similar display of manners from the wounded yet ultracareful Jackie, the one Kennedy with whom she shared the most history. Not so. “And then,” Lady Bird recorded, sounding a bit perplexed, “I found myself in front of Mrs. Jacqueline Kennedy. I called her name and put out my hand. I hardly know how to describe the next few moments of time. She looked at me as though from a great distance, as though I were an aberration. I felt extreme hostility. Was it because I was alive? At last, without a flicker of expression, she extended her hand very slightly. I took it with some murmured words of sorrow and walked on quickly. It was somehow shocking. Never in any contact with her before had I experienced this.”

Jackie’s losses had again mounted. Two infants. One husband. Now a beloved brother-in-law. Defying the mythology of Kennedy stoicism in the face of tragedy, she had practically collapsed at one point during the ceremony. Making Lady Bird feel at ease, a skill Jackie had mastered between 1960 and 1963, was perhaps not her highest priority in 1968. Was it a measure of survivor’s guilt that Lady Bird had projected onto this potent encounter? She had every reason to feel it. Her husband was still alive, even if his presidency was politically moribund.

As Jackie, Coretta, and Ethel mourned their fallen husbands, Lady Bird felt especially helpless and purposeless. “Once again, the country is being revived by the sight of a Kennedy wife, behaving with perfect nobility,” the journalist Mary McGrory wrote of Ethel’s grace at the funeral. Perhaps the hardest truth was that there was nothing Lady Bird, in her capacity as first lady, could do to provide comfort to the three widows or to a mourning nation.

IMAGINE IF SHE'D HAD TWITTER

Between November 30, 1963, and January 31, 1969, Lady Bird recorded 850 diary entries.

After Lady Bird returned to Washington, she spent the rest of the day unable to concentrate on work; she played bridge with her daughters, “hung in this interval of time between the funeral and the burial with everyone in a sort of emotional trance.” After a family dinner with Reverend Billy Graham, now a regular at the White House, the Johnsons were finally summoned to Union Station, where the train carrying Bobby’s body, Ethel and the Kennedy clan, and hundreds of friends, journalists, and political allies would shortly arrive. From there, the president and first lady would accompany the funeral cortege to the burial at Arlington Cemetery.

Inside the huge concourse, the vaulted doorways were draped in black, as the White House had been in 1963. The last time Lady Bird had been at Union Station as part of a funeral was for General Douglas MacArthur in April 1964. She stood then with Bobby Kennedy, still the attorney general, waiting for MacArthur’s train to arrive from New York. Bobby turned to her and said, “You’re doing a wonderful job.” He paused and added, “And so is your husband.” It was a single kind moment in an otherwise fraught relationship.

Overcome by Rose Kennedy’s suffering and also by her strength in the face of so much tragedy, Lyndon welled up with tears during the rainy ride to the station. Lady Bird tenderly touched his arm. When they arrived, they found Vice President Hubert Humphrey and his wife, Muriel, waiting, and invited them into the presidential limousine. “The ever ebullient” Hubert, then in the midst of what would turn out to be a successful run for the Democratic nomination, “looked for once drained and empty.”

The 21-car train that finally arrived carried what only a few days before was the nascent RFK administration. The Johnsons’ limousine followed fourteen cars behind RFK’s hearse. The motorcade’s route traveled from Union Station along First Street; turned west along Constitution Avenue, where it paused at the Justice Department, where Bobby had served as attorney general; and then west to the Lincoln Memorial, past Resurrection City, an encampment on the National Mall established in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination to highlight the indignities of poverty in America. There, under a bright moon, the cortege stopped.

Onlookers, at times six people deep, lined the lawns and sidewalks nearby. From Washington, Maryland, and Virginia, some from the South, others from across the country, they’d been waiting all day. The raised fists of the crowd at Resurrection City cut a dramatic contrast with the Cadillacs and National Guardsmen posted nearby. The Marine Corps brass ensemble accompanied two local choirs to perform “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” But the Secret Service cautioned Lady Bird against lowering her window to listen to the abolitionist Julia Ward Howe’s classic of the American songbook.

People, more people, candles in hand, lined Memorial Bridge across the Potomac to Arlington Cemetery. There, too, Americans had been waiting for hours to see the cortege pass. Inside the gates of the cemetery, more candles still. The Kennedy family friend Bunny Mellon had selected the grave site, on a slope shaded by two magnolia trees, “right close to President Kennedy’s tomb,” Lady Bird recorded.

Joe Califano, one of LBJ’s top aides, had negotiated every detail of the Johnsons’ role for that day. Going over the choreography, Califano had told the president that when the flag came off the casket, “they want you to present it to Mrs. Kennedy,” to Ethel. “I’ll be glad to do it, but I want you to make sure that this is what the family wants,” LBJ replied. Califano reassured him. “Yes, sir,” he said, “we have asked them three times.” LBJ said later that he was glad his last meeting with Bobby, a couple of months earlier, the day before MLK’s assassination, had been at least outwardly friendly. The day after RFK’s funeral, New York Times journalist Max Frankel captured the two men’s “braided” fates:

“Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy thought of each other as unruly detractor and unqualified usurper and their thoughts of each other could provoke them to private profanity. Yet they fought by the proper processes and peculiarly respected even what they resented. For a decade their lives were tautly intertwined, and as they pulled apart politically, they managed only to strangle one another.”

Lyndon was confounded by his inability to read the Kennedy clan and deeply frustrated by their rejection of his talents during his years in the White House.

In the end, after a brief ceremony, the Johnsons hung back. They stood when the family stood, kneeled when the family kneeled, and watched as one of the pallbearers, astronaut John Glenn, folded the flag with military precision and handed it to Teddy Kennedy—and Teddy, not LBJ, carried it to Ethel. “This was,” Lady Bird recorded, “as it should be.” Knowing the family’s wish to “linger alone,” the president and first lady said their goodbyes to Ethel and walked down the slope, Washington’s monuments and the Capitol dome illuminated ahead of them. “There was a great white moon riding high in the sky—a beautiful night,” Lady Bird recalled. “This is the only night funeral I ever remember, but then this is the only [such] time in the life of our country—an incredible, unbelievable, cruel, wrenching time.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Alone in a Crowd.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- LBJ

- Lady Bird Johnson