In his role as the Greek deity Hades in The Vortex Odyssey—a drive-through theater production staged by the Vortex theater company of East Austin—Michael Galvan stands in front of an ominously lit launderette loading dock, waiting on the next group of audience members to pull up to his station. The 23-year-old Arlington native doesn’t mind lip-synching to a prerecorded dialogue track. Nor does he seem fazed that blinding headlights from audience members’ cars prevent him from seeing beyond his own hands outstretched in front of him.

It’s the toughest role yet for the actor, whose fall 2019 turn as the domineering Beto in Krysta Gonzales’s one-act play Más Cara netted him an acting nomination in the B. Iden Payne awards—the city’s top theatrical honors. But in a time when nothing seems normal, acting in a drive-through is close enough to the real thing. “My biggest fear is losing the momentum I’ve worked for,” Galvan says. “At this point, I’m grateful for any work where I can use my art form.”

Ten months ago, the coronavirus pandemic darkened Texas’s stages indefinitely. But theater companies and artists across the state have taken steps to return to performance, and connecting with audiences, albeit in new ways. Up north, Dallas–Fort Worth theater companies such as Stage West and Teatro Dallas have produced a wealth of livestreamed and in-person productions, including the latter’s November production, Mike Soto’s “narco acid western” play, A Grave Is Given Supper, in which actress Elena Hurst performed solo for 24 audience members per show on the Dallas Latino Cultural Center’s outdoor plaza. And San Antonio’s Botanical Garden has become an impromptu performance space, with groups including the Classical Theatre of San Antonio and the children-focused Magik Theatre staging distanced productions in this lush outdoor venue.

Of course, the challenges underlying COVID-era theater-making are hardly exclusive to any particular scene. But for Austin-based playwright Virginia Grise, the capital city’s “pandemic theater season,” as she’s taken to calling it, represents something especially unique: a level of creativity she’s not seen since nineties-era Austin. “Back then, you would see these wildly imaginative, experimental pieces of work coming out of the city,” says Grise, citing the work of such artists as Daniel Alexander Jones, Sharon Bridgforth, and the city’s still-operational avant-garde theater collective the Rude Mechanicals. “Rent then was cheap enough that artists had the financial stability to live in that place of sustained curiosity,” she adds.

Now, with Austin’s fractured artistic community left stewing for months in its pent-up creativities and frustrations, Grise has witnessed the scene again grow bolder and more esoteric, yielding such socially distanced adaptations as telephone dramas, plays by mail, and even drive-through performances. “I feel like we’ve shifted back into this place of extreme exploration. Artists are not preoccupied with ‘how does this thing get produced?’ They’re just doing it. That’s the spirit of Austin I fell in love with.”

But such a return to creative form doesn’t happen overnight. In the weeks immediately following Austin’s lockdown, more than half of local theater groups worked at breakneck speed to pivot from live programming to virtual performances, including play readings over Zoom, livestreamed performances, and prerecorded short films. While the move temporarily helped some companies see their halted productions through, it also resulted in a glut of online-exclusive productions—to the point where the B. Iden Payne awards council created a new digital-performance category just to keep up. But “Zoom fatigue” has only left thespians hungrier for more meaningful and intimate avenues of expression.

That’s what led dozens of local artists, including Galvan, to jump at the chance to join an ambitious production such as Odyssey, which ran in early October. For Vortex technical director Teresa Cruz, creating eleven total performance installations for audiences to view from the safety of their cars was no small feat, even by pre-pandemic standards. “The fact that [fifty artists] together accepted this gargantuan task, not knowing what the rate was going to be, is—in my opinion—proof of the magic theater inspires,” Cruz says.

Using Homer’s epic poem as a loose inspiration, musical vignettes by more than a dozen local playwrights and composers served as canvases for Odyssey’s 11 feats of costume and set design. In station number four, set in a residential East Austin neighborhood, Hayley J. Armstrong’s performance as enchantress Circe—clad in an elegant blue silk robe, a golden seashell crown, and a studded black face mask—was a master class in how and actor’s eyes alone can convey worlds of emotion. Two stations down the road, in the Cyclops’ lair (staged outside of a shuttered storefront), audiences encountered a lumbering cyborg, complete with a fully functional mechanical forearm that actor Kami Cooper pulsed in rhythm to a techno-inspired earworm.

The technical prowess required to mount this, not to mention the necessary financial buy-in, makes Odyssey more of a onetime show of artistic resilience than a realistic model for future pandemic-era productions. For Austin’s cash-strapped theater companies, survival means risk-taking adaptation. “Right now, across the globe, theater artists are grappling with ‘What is theater—what separates us from TV or film?’” says Nicole Oglesby, co-founder of the Austin-based Heartland Theater Company. “[The question] for us becomes ‘How can we create an inherently theatrical experience in our current moment?’” Adds playwright Krysta Gonzales, “Theatermakers have this breathtaking ability to work within new limitations. Now that we’re working within a different container, we’re seeing the definitions of theater shift.”

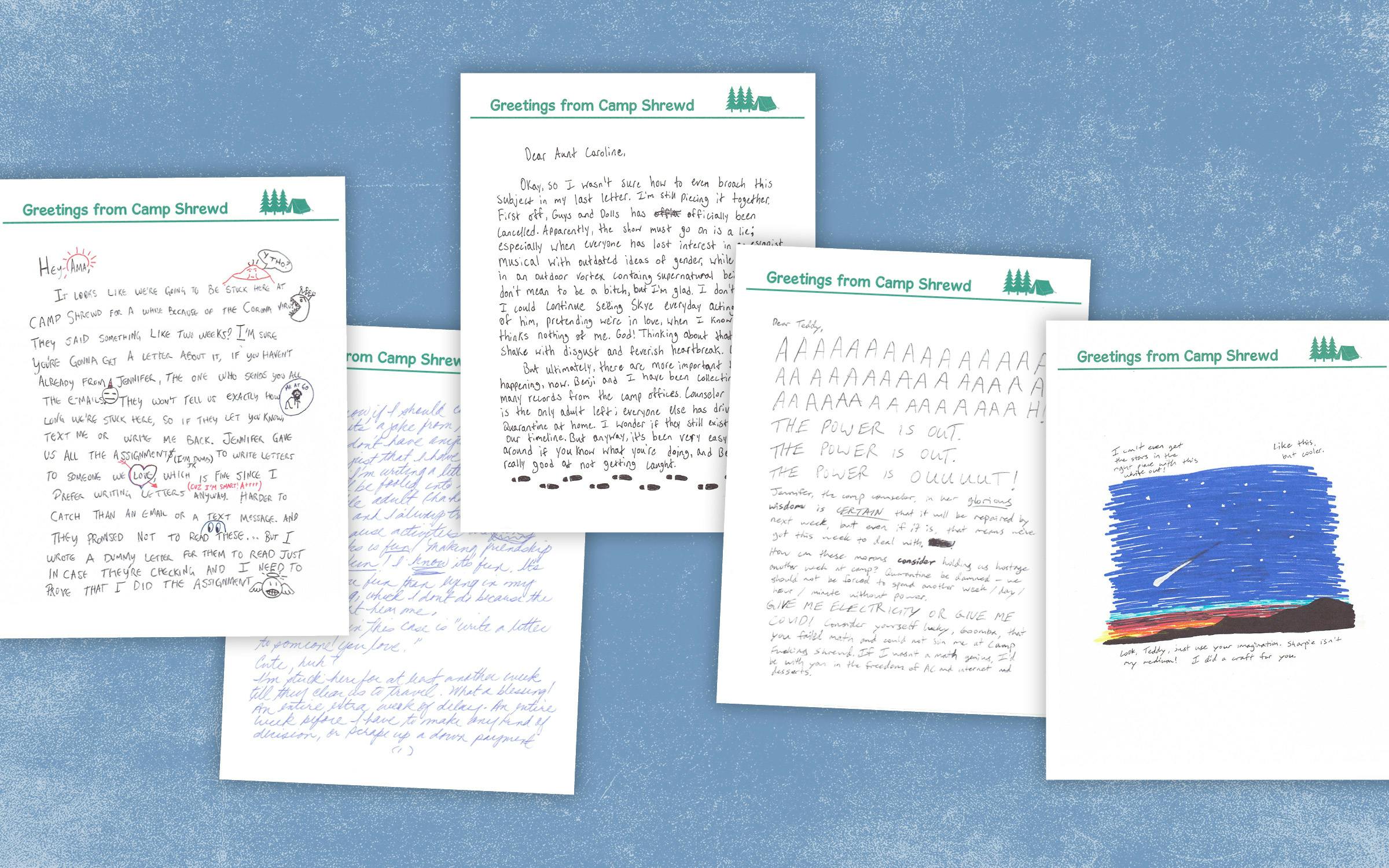

Gonzales’s first attempt at post-virtual pandemic theater involved rethinking the traditional actor/audience dynamic entirely. The latest from female-focused theater collective Shrewd Productions, Letters From Camp Shrewd, was an innovative play-by-mail experience. In it, the company presented an episodic mystery set in a children’s summer camp cut off from the outside world. A blend of horror, nostalgia, and fantasy, the play “came out of the question [of] how can we offer something tactile–something worth waiting for—in a time when everything is on screens,” says Shannon Grounds, the company’s founder.

Letters From Camp Shrewd’s unique concept, in which audience members were mailed a handwritten, story-advancing letter each week from their assigned character, was first conceived by Grounds and company member Anne Hulsman, and then developed by playwright and frequent Shrewd collaborator Reina Hardy—whom Grounds chose for her writing’s “innate whimsy.” From there, four additional playwrights, including Gonzales, were brought on to write a narrative from the perspective of one camper. “It was improv-style writing,” says Gonzales, “stealing story nuggets from each other and building these rich experiences based on how our characters would relate to one another. ‘Oh [fellow writer Briandaniel Oglesby] put this detail in his character’s last letter? I’ll build off that, see where it leads.’”

Grounds intended Camp Shrewd’s narrative world to be highly immersive for participants, which is why in addition to having each playwright customize the letters with unique doodles and drawings, each installment was also shipped with a different handcrafted souvenir from the story. Thanks to an idea inspired by the trinkets company member Anne Hulsman received from her own childhood pen pal, audience members were sent custom friendship bracelets, foreboding cootie catchers, and even confetti bombs courtesy of Benji, the camp’s resident prankster.

Each night, Shrewd’s social media pages came alive with audience members eagerly discussing the ongoing narrative as they received updates in the mail. What’s more, Grounds says she often received emails from patrons injecting themselves into the story—role playing, for instance, as campers’ concerned relatives. “The goal with Camp Shrewd was to give audiences a feeling of connectivity when we’re all so separated,” Grounds says. “For that reason, I was never worried that we’d stray too far from the craft of theater, as it were. It’s a story. And we’re interacting with people. To me, that’s the basis of the art form.”

For Ryan Crowder, artistic director of Round Rock–based Penfold Theatre Company, interaction-heavy productions like Camp Shrewd are key to maintaining meaningful connections with fans in our remote new world. ”The thing about theater is it’s an inherently immersive experience—even if it’s not expressly billed as ‘interactive theater,’” he says. “The event is unfolding around you in this space. Having a tangible element brings you into a world where this story could be true.” Crowder would know—he applied the same mind-set to Penfold’s own interactive play from home, The Control Group, an otherworldly, time-hopping sci-fi mystery delivered via telephone.

Conceived by playwright Monica Ballard, this sprawling weeklong production, which ran for five weeks from October 19 to November 20, is one Crowder compares to three plays unfolding at once. Built around the narrative premise that something’s gone disastrously awry in a future timeline and only the audience can correct it, The Control Group consists of a daily phone call between an audience member and “Director D’Souza,” head of the fictional shadowy government agency that gave the production its title. Peppered throughout audience’s one-on-one conversations with D’Souza (a character portrayed by seven actors, each of whom were assigned their individual audience member at the outset of a performance week) are several prerecorded field reports from other “members” of the control group. “Those are basically audio dramas; you’ll get a field report from say, an agent in 1944 and then another in the sixties,” Crowder explains. What’s more, audience members are mailed a case file at the show’s outset, featuring “classified” dossiers, photos, and other documents.

Ultimately, The Control Group is less about unraveling a mystery and more about the real-time interplay between D’Souza and the audience members. “It doesn’t get much more intimate than doing theater over the telephone,” says veteran theater maker David Jarrott, a Texas Radio Hall of Fame inductee and one of the actors recruited to play the role of Director D’Souza. “When you’re on the radio, you’re talking to one person at a time, not thousands. It’s a similar concept with Control Group. You have to establish trust immediately from that first phone call […] I’m always taking notes to refer back to; recalling something as simple as my audience member mentioning their dog’s named Sparky goes a long way to making that one-on-one bond even more secure.”

While artists including Grounds and Crowder will tell you their companies’ new immersive productions are nothing more than a temporary pivot from the straightforward work they’re used to, industry veterans, including event producer Justin Sudds, feel that the shift toward more interactive programming was going to happen anyway. “Right now, we’re seeing wide acceptance of these new immersive shows out of sheer need,” Sudds says. “But take the pandemic out of the equation and there was already a clear trend moving towards such programming.”

As the cofounder and executive producer of the Canadian production company Right Angle Entertainment, Sudds noticed that his industry began to shift toward more immersive experiences around 2012, around when he was producing the touring stage version of TV game show The Price Is Right. Surprisingly, Sudds says, the decades-old property, which relies entirely on audience participation, sold well among audience members ages eighteen to forty. And the producer would see this trend repeat over subsequent years, most notably when he was helping to create live shows for rising social media influencers/celebrities, including popular YouTube gaming personality Mark Fischbach, a.k.a. Markiplier. “You’d start seeing audiences [that] would utterly reject a show that wasn’t interactive … Now you’re designing shows to have as much interactivity as they possibly can, where the audience feels like they’re getting a unique experience every night.”

Sudds’s first step into post-COVID performance production was the show Art Heist, an easily adaptable urban walking tour that hinges on audience interaction. The ninety-minute family-friendly program, which Sudds coproduced for Montréal’s socially distant 2020 Fringe Festival, features groups of participants traveling from one performance station to another, interacting with live actors to solve the mystery of the 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum robbery.

Following Art Heist’s warm reception in Canada, Sudds brought the show to Austin in October, staging the show with local performers and creatives around Congress Avenue’s historic Paramount Theatre. After a massively popular proof-of-concept staging, one that saw the show’s Austin run extended from three weeks to six because of high ticket demand, Sudds plans to stage Art Heist in dozens of cities across the United States. “If you told me eight months ago that I was going to be producing shows for 35 people [at a time] in Austin, Texas, that’d have seemed crazy,” he says. “But it’s an effective business model, and I believe we’ll see many more similar models brought to market in 2021.”

Looking at the number of interaction-heavy productions set to premiere over the coming months in Austin, it seems Sudds might not be far off. Cyrano Plays, a performance-from-home concept that erases altogether the line separating audience and actor, debuted in December courtesy of acclaimed experimental performance collective the Rude Mechanicals (or Rude Mechs). Founded in the late nineties by five UT Austin alumni, the Rude Mechs have long worked to carve out a distinct niche in Austin’s theater scene, staging many outlandish live productions, all sharing a gleeful defiance of convention. The most recent example of these shows, Not Every Mountain—a poetic meditation on change and destruction—saw performers spend an hour constructing a fifteen-foot mountain from cardboard and magnets, only to topple the structure at the show’s end.

So, when the Rude Mechs approach a work like Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, it’s safe to assume they’re doing so with a form-bending trick or two up their sleeves. Enter the group’s long-awaited smartphone app, Cyrano Plays—quite possibly the future of interactive performance, or at least a memorable way to stage a play from one’s living room.

Designed by a number of local developers, the app’s user experience is described by the group as “33% charades, 33% karaoke, and 33% great storytelling.” As far as setup goes, audience members gather in (socially distant) groups of four or more (eight is recommended for this particular production), download the app, and pick which characters they each want to play. When the time comes for each actor to speak, sing, or move, Cyrano Plays whispers, via earbuds, instructions and lines—which participants emulate to the best of their ability (hence: karaoke).

After meeting the project’s crowdfunding goal last October, the company released the app’s first interactive offering, A Karaoke Christmas Carol, to Kickstarter backers in December. “Christmas Carol is the one play even people who don’t like theater usually go see,” says Kirk Lynn, a cofounder of Rude Mechs. If you’re going to see this play with your aunts and uncles already, why not instead make it in your own house, save a bunch of money, and laugh your ass off as Uncle Artie falls on his face trying to play Marley?”

While his team rigorously tested Cyrano Plays to ensure it would work in a various holiday-party circumstances (for example, with drunk or sober participants, with experienced actors or without them), Lynn believes the show’s humorous unpredictability is key to its charm. “We’re fans of embracing that chaos. One, because wildness is fun—there’s a part in the show where everyone sings ‘Carol of the Bells’ at once and the echoes make it sound psychotic, like Christmas on LSD—but also because [Cyrano Plays] is about experiencing theater’s unique liveness together. There’ll be some performances that are gorgeous and tearjerking, and nobody will ever see it save for the one family in the room that night.”

Following Christmas Carol Karaoke’s limited debut, Lynn says the app will be released fully around Valentine’s Day. At that time, audiences will be able to access a similarly interactive production of “Pyramus and Thisbe,” the play-within-a-play staged by in Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream by fictitious performance group the Rude Mechanicals (and from which Lynn’s company derives its name). And the team isn’t ruling out including Karaoke Christmas Carol with the app’s February release, but Lynn says they may wait until the next holiday season to do so.

Lynn is more than aware his latest production will capped what can only be described as the worst year for Austin theater makers in recent memory. Still, the UT theater professor sees a silver lining in the creative productions that groups like Shrewd, Penfold, and dozens of other companies are staging. “For a while [pre-pandemic], it seemed that theater only wanted to get bigger. ‘Can we create a show for two thousand people?’ That seems less safe right now, but maybe it’s also less valuable,” Lynn says. “It’s my hope that shows that value the connections theater fosters—over an obsession with slick production—keep coming forward.”

Going into an uncertain 2021, the scene’s many weary theater artists say there’s comfort to be found in the art form’s resilient nature. “Theater has existed since humans could dance around fires,” says Oglesby. “It’s in us to tell stories. To create.” Adds Lynn: “The essence of theater is that a bunch of weird people want to get in a dark room and make something happen. People will always want to do that.”

As Michael Galvan wraps up his final performance as Hades in Vortex’s Odyssey, a group of inebriated passersby stumble upon the actor’s drive-through set. Curious, they stay to watch Galvan’s final soliloquy as the ruler of the underworld, which the actor now delivers with renewed vigor, relishing what would be his last performance for a live, tangible audience in 2020—and likely a long time after.

“All throughout the production, people would drive up asking, ‘What is this? What’s happening here?’” says Vortex founder and Odyssey director Bonnie Cullum. “To me, that was the most joyous thing about Odyssey: This sort of genuine disbelief that theater could actually be happening during a pandemic.”

Update 1/12: A previous version of this article stated that Ann Marie Gordon had come up with the idea of trinkets for the Camp Shrewd production. The story has been updated to reflect that Anne Hulsman conceptualized the idea.