Fernando A. Flores was born in Reynosa, Tamaulipas, crossed into United States as a young child, and was raised in a trailer in the Rio Grande Valley town of Alton. Though he’s very much a product of the region, his work has acted like an incursion on the area’s abiding literary conventions: his fantastical stories question the widespread assumptions that the border is anything more than an arbitrary delineation and that the Mexican Americans of the Rio Grande Valley are a backward people of scant literary sophistication.

Three books into a sui generis career, Flores represents a breakout from the strictures of social realism and documentary historical fiction, into a delirious literary mashup that conjures up the Texas writers Gloria Anzaldúa and Americo Paredes, as well as Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka, and Iggy Pop—an autochthonous punk-rock magicalism of the borderlands.

Flores’s first book of short stories, 2014’s Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas, Vol. 1, assembles outlandish tales of punk rock bands in the Valley. In one yarn, “The Eight Incarnations of Pascal’s Fifth,” a group of musicians reincarnate through the ages, as green-skinned children in a small Scottish village, as cloistered Mexican nuns, as militants taking on Sam Houston’s and Santa Anna’s armies, and, finally, as an experimental art-rock band in Port Isabel. His 2019 debut novel, Tears of the Trufflepig, depicts a near future in which narco lords have created an industry in the South Texas brush country, genetically engineering hybrid animals for the amusement of the super-wealthy.

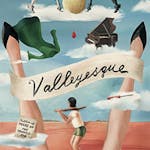

In Valleyesque (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Flores’s new collection of short stories, we encounter a shamanic version of Emiliano Zapata emerging from a mural; a couple nurturing a “baby” they’ve made out of their earwax; and the Polish composer Chopin, roaming the streets of Ciudad Juárez. A character in another story articulates Flores’s literary orientation, saying, “I feel I can reveal more by writing stories in the traditions of hard-core, maybe weird literature, rooted in something old and unknown, and infusing it with my life and where I come from, as unintentionally as possible.”

Flores lives with his wife, the Russian-born poet and fiction writer Taisia Kitaiskaia, and their dog, Adira, in a shaded bungalow in Central Austin. His study, where we had this conversation, is crammed with neat piles of books and a large collection of vinyl records in plastic sleeves, fastidiously arranged on shelves. At his writing desk, there’s a small portable Olivetti Underwood Lettera 32 manual typewriter, on which he composes all his work. A completed next novel, in marked-up typescript, hangs nearby from a clip on the wall.

Texas Monthly: Did you grow up going back and forth across the border?

Fernando A. Flores: Almost every weekend. My mother’s side of the family was very close. So we’d go to Reynosa to visit my grandparents every other Saturday. I was very connected to Mexican culture, to Mexican pop culture. I got to see how American culture is just everywhere over there; my cousins were obsessed with it. And I was living on this side, so I could connect with them.

Reynosa is such a strange city, it’s a mixture of all kinds of things. It’s very urban, more urban than South Texas. Everything’s more concentrated than where we lived, which was very rural. I grew up with a lot of really mean boys, and I was always an easy target to be bullied. I’d read the Lord of the Flies, and it was real for me in many ways. Growing up, you had nothing to do. You’d just walk around the orchards and stuff like that.

TM: How did the artistic impulse set in for you?

FAF: When I was in high school, maybe junior high, the American Film Institute released a list of its hundred greatest movies of all time, and there was this special about it on TV. They interviewed the movies’ screenwriters and directors, which were concepts that I’d never really thought of. So I became interested in storytelling that way. Those are the first stories that I really related to.

I ended up printing out the list in my computer class, and when I rented movies, I’d look for one of those films and cross it off the list. I just became obsessed. I’d drive around, looking for VHS cassettes.

TM: Any filmmakers who particularly influenced you?

FAF: Something that really inspired me was how [the screenwriter and director] John Cassavetes didn’t care about being totally broke. He’d refinance his mortgage and act in movies that he didn’t want to be in just so he could finance his own projects. And it’d take him five, six years to finish a movie because he’d make them in this way. It was inspiring to me how his entire life would fall apart every time he tried to make a movie. I realized I could be happy, even if I was totally broke, if I was always creating something.

TM: And all of that turned you into a writer?

FAF: Because of this whole cinema thing, I was interested in how to write screenplays. I read Syd Field’s famous book about how to write a screenplay, I read William Goldman’s books about Hollywood, and it was the first time I paid attention to a screenwriter who eventually wrote a novel. It’s rare for a screenwriter to cross over into literary fiction and be popular. I think that influenced me in some kind of way.

TM: How did you decide you wanted to tell stories set in the Valley?

FAF: I had a lot of crazy friends growing up. And movies like Independence Day would come out and we’d always wonder, “Why can’t we be attacked by aliens?” In the movies you see them in New York City and Los Angeles or whatever. But aliens attacking all these Mexicans in the Valley—to us, it was just really funny. So I was like, “Yeah, why not write a weird, sci-fi kind of story that takes place in South Texas? Why do we allow the conventions of publishing to tell us what kinds of stories we can tell about our culture and our region? Why do we allow those things to dictate our art?” I spent my twenties and my youth taking in Mexican American literature, which was very realist, and I was like, “If I’m going to write something that is realist, it’s just going to be a reflection of what these writers have already done and already done very well. What am I adding to literature that is interesting, even to me?”

I spent a long time writing material that ultimately I was not satisfied with. Tears of the Trufflepig is my first published novel, but it’s my third or fourth novel, really. If I would’ve known back when I was working on those novels that they wouldn’t be published, I would’ve probably gone crazy or something. Because you never think about these things. It isn’t until you have it in your hands that you can see the failure. That’s why I type my work out—I like to see the error on the page. I like to see my mistakes on the page; I learn from that.

TM: What were those early attempts like?

FAF: I wrote an autobiographical novel, and I liked it. It had my voice and my experience in it. But I was like, “What is it really doing? Why do I want this out there? Just because I wrote it?” I really had to ask myself all these difficult questions.

TM: Your first book of short stories won you an honorable mention for the Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Prize, granted by Sandra Cisneros, which came with a check for $10,000. How did that affect your career?

FAF: For the first time in my life I had a chunk of money and time, and I was like, “Am I going to revise my first-person autobiographical novel? Or am I going to try and do something new?” The idea of doing something new just seemed scarier and more fun. So, out of sheer fear, I wrote Tears of the Trufflepig in three months, and I was happy with it. I had never done anything like it. That’s where my writing really changed. I forced my writing to change when I was in my early thirties. I allowed myself to break all the rules of writing and avoid the low-hanging fruit, like writing about being an immigrant in an obvious way.

TM: What sorts of experiences affected that change?

FAF: I read a lot. That’s pretty much what I do. I never go anywhere, do anything, really. My life is pretty much reading and taking in art and literature. I read a lot of musical stuff, like essays by [the Hungarian classical composer Béla] Bartók.

My approach as a writer is inspired by [the visual artist] Joseph Cornell, who made these boxes that were collages of found objects; he’d create a narrative out of those pieces. To me, that was very inspirational, to be able to find things around your neighborhood and create a narrative out of it. That’s how I approach writing—all these little things that I find in my everyday life and that I pick up in my reading come out in these stories.

TM: Your stories are always giving evidence of something that’s going on deep underneath the visible world of the Valley—something that’s taking shape at a subliminal level. What is it about the Valley that is so protean, so full of wonders and horrors and things that are shocking, things that are endearing?

FAF: I’ve been saying that Valleyesque is the third and last book of my South Texas trilogy. It’s an unofficial trilogy, but the binding thing about all three are myths. Bullshit Artists of South Texas deals with these music-scene myths—these artists who come and go, who are unsung, and who are eventually forgotten, but who are mythical nonetheless in a certain underground scene. Tears of the Trufflepig dealt more with dreams and actual mythology and legends and death.

And then with Valleyesque, I thought about works like Plutarch’s Lives, which are these capsule mini-biographies of important people, and Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives, which was published 120 years ago and deals with historical figures in a fictitious way. Every short story in that book is about a famous person in history but it doesn’t deal with a major moment in their lives, but with a mundane, almost insignificant moment.

To me, these concepts were funny. And then there are all these South American writers, like Roberto Bolaño in Monsieur Pain, who would have a cameo of a famous person in their novels. So I thought about all these people who are always wandering around Texas, these mythological figures, like Lee Harvey Oswald [who appears in Valleyesque]. When the violence on the border was really bad, about ten years ago, I was listening to a lot of Chopin, so something about Chopin and border violence emerged, and that’s how that story came about.

TM: What do these stories tell us about the Texas borderlands?

FAF: There’s some kind of unexplained meaning about this area that I’m still trying to discover. When there’s a big global disaster, the refugees always end up on South Texas’s border, because that’s the way to cross. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the Ukrainian refugees ended up at the border, and so did the Haitian refugees who left because of that terrible earthquake years ago. All these people from all over the world end up there, and at the same time, Elon Musk is launching rockets from South Texas that may get to Mars. The border becomes the border not only between the United States and Mexico but also the border between Earth and Mars.

To me, that’s the mythological significance of South Texas, and it’s been my obligation, I felt, to try to access it. And now that I can see all three of these books, I feel that I did what I set out to do, even if I didn’t have a legit agenda.

TM: Many readers see magical realism in your work. Is that a literary style you associate with your writing?

FAF: “Magical realism” is a term that everybody has their own definition of. I think that’s maybe why I called this book Valleyesque. I wanted to have a word that was sort of like “Kafkaesque” or “Felliniesque.” It kind of describes a genre beyond the author. You can describe something that’s not written by Kafka as “Kafkaesque.” I wanted to have a word that was geographically attached to the Valley that also was maybe an adjective to describe weirdness.

When most people say “magical realism,” they really just mean [Latin American writers] like Gabriel García Márquez. Whenever somebody calls my work “magical realism” or anything like that, I’m okay with it, but I would never call it that myself. “Magical realism” is a strange term. We don’t call Shakespeare a magical realist, even though all these weird things happen in his plays. Hamlet’s father’s ghost is in Hamlet. You’d never say Don Quixote

is magical realist, even though a bunch of weird magical realist things happen in it, you know? Or Kurt Vonnegut. Nobody says Kurt Vonnegut is a magical realist, even though the same rules apply to his work that would apply to García Márquez.

So it’s an interesting term, but to me it’s not applicable to what I do because I’m from the border, and I can’t think of any magical realist authors who come from where I come from.

I feel more like an outsider than ever among the literary fiction community—especially among the Mexican Americans. Lord knows I’ve tried to fit in. I hate to say it, but when I was starting out, all the literary magazines claiming to be representative of Chicanx or Mexican American literature were the first to consistently reject my work—even the agents and editors who had a reputation for championing this type of material. These are the people who avoid me now too, so it’s still isolating. I write stories that are not easy to classify. I’m forty years old now, older than your average author who’s this early in their career, and it took a tremendous amount of work to finally get my books published.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Fernando A. Flores Is Bringing to Life the Punk-Rock Magicalism of the Texas Borderlands.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books

- Writer

- Rio Grande Valley

- Austin