In September 2017, as the narratives that would become the #metoo movement began to take shape, the Baylor University chapter of It’s On Us—a national organization that works to destigmatize sexual assault and provide an outlet for survivors to heal—gathered in the food court to discuss how to bring that conversation to campus. Earlier that week, I had been scrolling mindlessly through Facebook when I saw an article about how Kansas University’s installation of “What Were You Wearing?” displayed re-creations of the outfits people had on when they were sexually assaulted: a child’s sundress, a man’s gym clothes, a woman’s swimsuit. As a survivor of sexual violence myself, I found the anonymous, yet deeply personal nature of the clothes to be a meaningful way to share the stories of survivors. After I brought the article to our next meeting of It’s On Us, our members—five of us on a good day—decided to stage a similar event at Baylor in April.

This conversation was especially important to have at our school, which has been plagued by sexual assault controversies in recent years. After the highly publicized convictions of Baylor football players Tevin Elliot and Sam Ukwuachu in 2016, over a dozen survivors sued the university, alleging that their reports had been mishandled and covered up to protect the players. Other students then brought allegation of sexual assaults at fraternity parties and dorm rooms to the public, revealing that the incidents extended far beyond the football program. In response, the board of regents fired football coach Art Briles, athletics staffer Tom Hill, and Baylor president Ken Starr.

Two years later, Baylor’s Title IX department had hired new staff members experienced in addressing sexual assault cases, streamlined the reporting process, and rewritten its policy to better protect survivors. But campus conversations hadn’t progressed significantly. I would overhear my peers casually discussing (and sometimes even joking about) how an accuser should have expected to be raped after going out late at night or wearing such a short dress, but they’d never earnestly talk about how they, or Baylor as a whole, could make meaningful change. The conversations were rarely about supporting survivors, but instead about which coach was fired or which fraternity would be suspended. It was as if the only time someone cared about rape was when it affected an organization they were a part of.

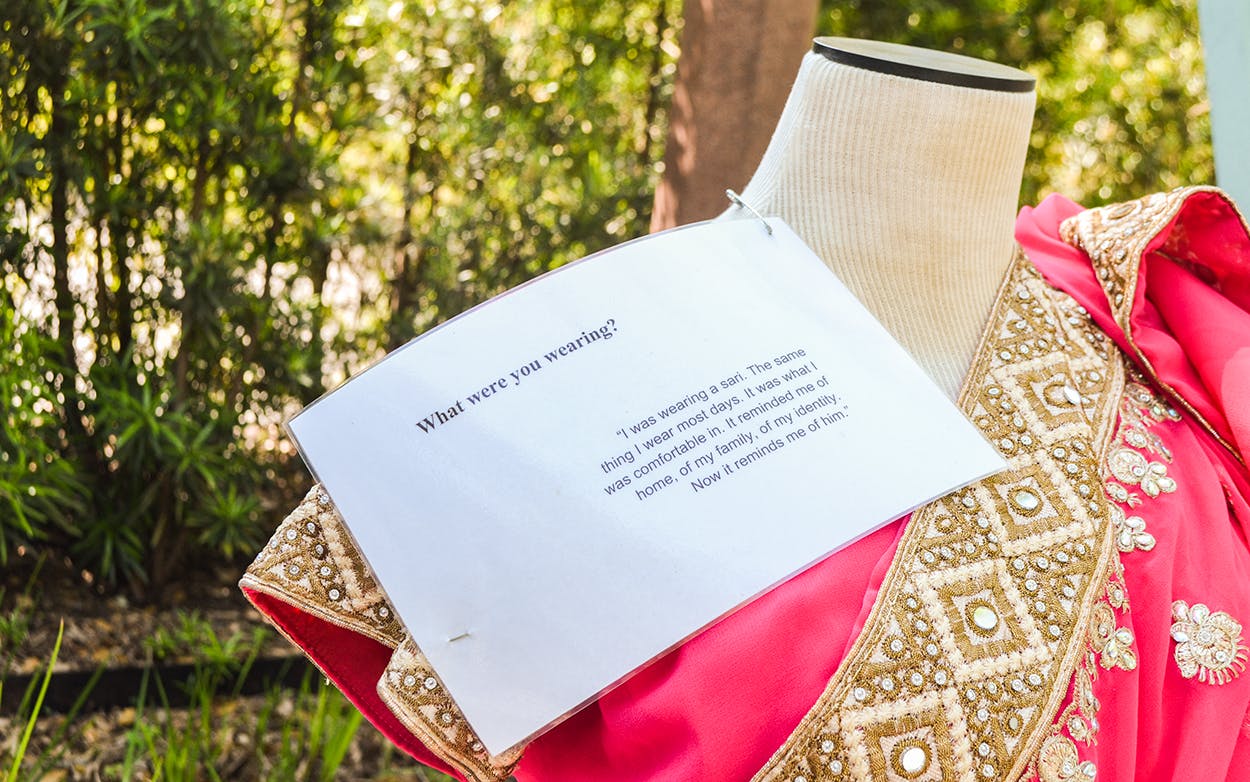

It’s On Us decided to create an exhibit depicting the varied experiences of sexual abuse survivors around Baylor—not just following the narrative of the rapist in a dark alley, but looking at the coworker at CVS, the study partner from math class, the family friend during a barbecue. The five of us made calls, collected clothes, and raised money. We partnered with Baylor’s Title IX department, the Waco Advocacy Center, and the Waco Family Abuse Center, and gained sponsorships from local organizations and businesses like Baylor Student Government and local bar Austin’s on the Avenue. We wanted to communicate the experiences of as many survivors as possible, so we posted on Baylor Facebook pages and left a drop-box at the Waco Family Abuse Center where survivors could donate their clothes and share their stories.

Unlike at other similar exhibits, like at the University of Kansas or Henderson State University, we decided to nail the clothing to teal doors, to represent how we wanted to open doors to new conversations. As we stood in the president’s backyard, carefully arranging the outfits to represent the height and size of the survivor and painting rape statistics on the doors, we sometimes chatted, but oftentimes worked in silence, shaken by the relics of so much pain.

When visitors walked through a teal door frame into the exhibit, they encountered the narratives through a semi-circle of doors, each with an outfit nailed to it. One door held a pink, flowery swimsuit and was painted with waves lapping at its feet. Another looked like the door of a dorm room, decorated with a “freshman” sticker and displaying a Baylor University sweatshirt and sweatpants. One door, which I could never look at for too long, held a small child’s dress, so small that the fabric only went up a third of the door.

At first, we planned for the exhibit to last a week or two on Baylor’s campus. Then, just weeks before the exhibit opened, McLennan Community College reached out and asked if they could display a few of the doors on their campus, and other local organizations followed. In total, “What Were You Wearing, Waco?” was displayed at twelve locations across the city over the month and was visited by over 2,000 people. On Facebook, hundreds of thousands shared and commented on photos of the exhibit, excited to see a shift in Baylor’s narrative.

As the president of It’s On Us for the 2018-2019 school year, I spent most days at the exhibit, either at the campus location or at the exhibit outside a local bar, keeping an eye on the doors and passing out information on sexual violence and resources for survivors. Some people would walk by without looking. Others would read a few doors and leave. Many would walk slowly to each door and stand for a few seconds in reverence, like a visitor at a war memorial.

I heard comments of all kinds. “Are those boys’ clothes? That’s not possible,” said one woman, visibly shocked to see a middle school boy’s polo and khakis nailed to a door. “This is so powerful,” said another. “I think I own that dress,” a college student whispered.

The most meaningful reactions came from other survivors. They would always start the same way. A person would walk up to me and ask a few questions about how we got the clothes or what organization we were with. Then they would quietly say something to the effect that if “I had known you were doing this, I would have donated my clothes.” These conversations broke my heart every time. I could see how hard it was for these men and women to say the words out loud. I would ask them if walking through the exhibit was difficult, see how they were doing, and then point out which door was mine. Often, I would give them my phone number in case they ever needed to talk. Despite having worked with sexual assault survivors for over two years, I still feel guilty that I cannot take away their pain. I cannot throw their attacker in prison. I cannot keep them safe.

But not all of the reactions were supportive. One night, we were putting up the exhibit next to Austin’s on the Avenue. One of the doors, leaned up against a wall, displayed a basketball jersey and athletic shorts and told the story of a man who was assaulted by his long-term girlfriend. Suddenly, a drunk man stumbled into the exhibit, ripped the jersey off the door, and threw it down the alley. It was exactly what society has done to survivors for centuries: take our stories and toss them aside as meaningless. As a society, we too often silence survivors because it makes us uncomfortable to address the truth: rapists walk among us. Perpetrators commit these crimes unprovoked and they could attack someone of any age, any gender, in any clothing. The doors—one showing the rape of a child committed by a close family member, another of an assault by a girlfriend, a third of assault from a friend’s boyfriend—made that point clear.

The exhibit gave us a chance to host those difficult conversations among groups who don’t often talk openly about sexual assault, including several events at local churches. I hosted one discussion before a congregation of older, mostly retired professors about a proper Christian response to sexuality and sexual violence. After we finished our discussion, a man in his eighties walked up to me. He said he felt empathy for survivors because he was one. He told me how he was assaulted as a child in a small town by a public figure in the community, and said he spent years asking himself what he had done to provoke his attacker.

The elderly man looked like my grandfather. He had wrinkles, thin hair, and bright blue eyes, but as he told his story, I saw a ten-year-old boy still doubting himself. I realized at that moment how long society has allowed survivors to live with undeserved guilt, while perpetrators walk with clean consciences.

On May 5, a week after we took down the exhibit, our team of rag-tag curators and survivors gathered around a bonfire outside of Waco. Each survivor took turns speaking before tossing the clothes from their assault, letters written to their attackers, or pieces of the exhibit’s doors into the fire. Some cried as they spoke, tossing their effigies into the flames hesitantly. Others threw theirs in silently, with a deep and unspoken rage. One cracked jokes as she tore hers apart and watched the pieces burn. I cried harder than I had in a long time.

- More About:

- Art