This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

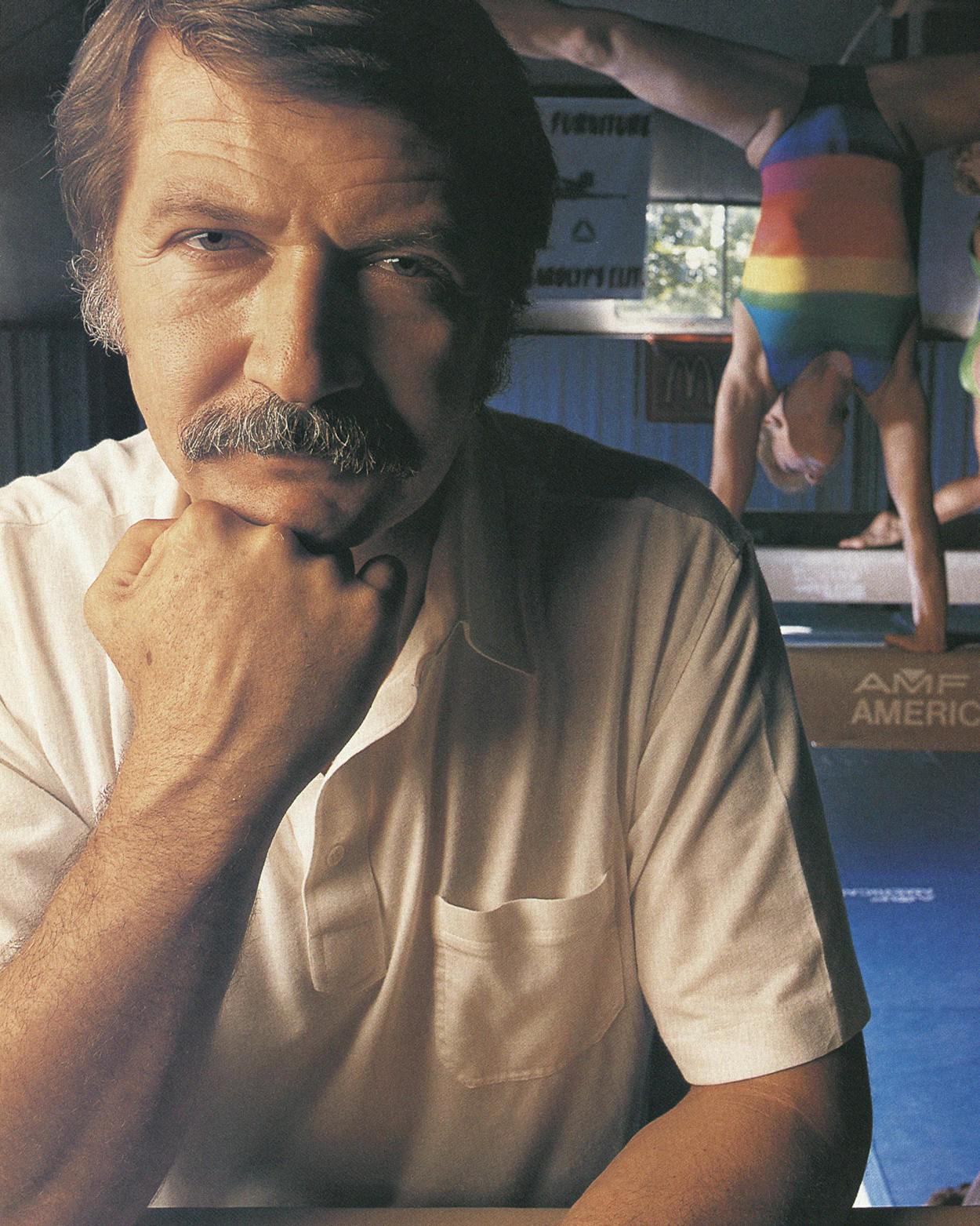

The five girls were at the uneven bars, busily rubbing chalk over their hands, their eyes aimed at the floor so they wouldn’t have to meet the smoldering stare of their coach. Bela Karolyi, the world’s most famous gymnastics coach, was furious at them again. In shorts, a muscle shirt, and tennis shoes, he stalked among the floor mats, his shaggy brown moustache drooping over the corners of his mouth, his arms held away from his waist like a gunslinger about to draw. “I’ve been telling you what to do,” he snapped in his thick Romanian accent. “Now do it!”

Fifteen-year-old Kim Zmeskal, the latest of Karolyi’s stars, twisted over the high bar and then, as she circled forward, dropped to the low bar. She almost lost her grip—for months she had been battling a stress fracture in her left wrist—but recovered in time to drop lightly to the floor. Karolyi stared at the heavens. “Holy cat,” he said (despite his having been in the country for a decade, his English is still somewhat perplexing). His huge body loomed over the four-foot-seven-inch Zmeskal. She looked up at him obediently, as she knew she must do, never complaining about her injury, never making excuses. “Kim,” he said, his dark eyes bearing in on her baby face, “that is sloppy as possible.”

If Kim was angered by the insult, she was smart enough not to show it. Any girl who crosses Bela Karolyi knows the consequences: He pushes her harder, acts even more derisive. The Bobby Knight of gymnastics, Karolyi rules his pixies through intimidation. He drives off the weak and molds the survivors exactly in his image. In practice, he allows no emotion in his gymnasts, no giggling, no crying. They do not speak unless spoken to.

“You, Betty,” he said, motioning to his other star, Betty Okino, a beautiful girl who, at the age of sixteen, has yet to find the time to learn to drive a car, let alone find a boyfriend, all because of her devotion to gymnastics. Still aching from a sore elbow that she broke a month ago in a practice session, Betty swung above the high bar. But in the process, her legs spread slightly apart. “No! What are you doing?” Karolyi protested. “Losing your mind? Do it again!”

It was a sultry evening in late July, and the five girls were sequestered inside a windowless gym on Karolyi’s ranch, seventy miles north of Houston. Members of Karolyi’s “elite” team, the young teenagers were among the most accomplished gymnasts in the world. At gymnastics meets they were treated like pop icons, surrounded by other children squealing their names, seeking autographs. In the next year they would have the chance to become Olympic heroines, the next Mary Lou Rettons, their faces on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

At the moment, however, they looked only like discouraged, sweat-drenched kids, their elfin bodies sagging with exhaustion. An atmosphere of siege pervaded the camp. Karolyi had kept his girls there all summer, working them seven hours a day, giving them one day off a week if they were lucky. Parents were allowed extended visits only on Sundays: One mother irritably began calling the ranch the Prison.

Karolyi, in typical fashion, showed no signs of letting up. If anything, he said, they should be training harder. The World Gymnastics Championships, the most prestigious event in the sport next to the Olympics, were only six weeks away, and Karolyi, the fifty-year-old defector from Romania, was determined to make his biggest breakthrough yet. He wanted to prove, for the first time, that his girls from Houston were better than the exalted Soviet and Eastern European gymnasts—that a U.S. team, under his leadership, could win it all.

“Go on. Do it now!” he commanded Erica Stokes, a fifteen-year-old with freckles and braces and auburn hair pulled back in a perky ponytail, a girl so enchantingly cute that the Minute Maid orange juice company featured her in a television commercial. At the age of six, Erica had sneaked away from her own backyard birthday party to watch Karolyi and his gymnasts in a televised gymnastics meet. By ten, she had left her family in Kansas City and moved to Houston to train with the great coach. Realizing that she was never going to quit, her father eventually asked for a job transfer and moved his family to Houston. Karolyi had great hopes for Erica; he once called her “the most coordinated gymnast I have seen in a long, long time.”

Then came a series of injuries over the past year and a half—ankle sprains, a pulled shoulder muscle, a split heel. She gained a few pounds, she lost confidence, she fell behind the other elite girls, and Karolyi started losing his patience. One of the worst sins in Karolyi’s world is self-doubt. He coddles no one; he never gives the old “come on, you can do it” speech. As Erica took to the bars, Karolyi folded his arms and cocked his head to study her movements. She landed a little too tentatively for his taste. With a great Balkan shrug of his shoulders, Karolyi lifted his arms, then turned away. In the silence that followed, the other girls kept their faces down. It’s one thing to be yelled at by the coach; it’s another to be ignored altogether. Erica, they knew, was in trouble.

Indeed, a week later, Erica—who had devoted five years of her life to Karolyi, whose parents had paid him around $350 a month in fees and spent thousands more in paying for her trips to meets around the world—was kicked out of the gym, told to pack her bags and leave. Karolyi said that she had become a distraction. She was holding back his top girls like Kim Zmeskal and Betty Okino. She was not working hard enough, he said, to become a world-class gymnast. When a weeping Erica left the camp with her mother, her career apparently at an end, the coach was not around to say good-bye.

Bela Karolyi is one of the most perplexing figures in American sports—a mysterious, untamed bear of a man dedicated to a bunch of teensy sprites who, even on tiptoe, can’t see over the top of a Volkswagen. At times, he is devastatingly charming, a master storyteller capable of regaling an audience, in that irresistible accent that reminds one a little of Inspector Clouseau, with one tale after another. Sportswriters chuckle throughout his boisterous press conferences. Worldwide TV audiences have grown accustomed to the sight of him bounding jubilantly across the arena to gather up his winning gymnast in a massive hug. At the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, when an emotional Karolyi embraced his student Mary Lou Retton moments after she had become the first American woman to win a gold medal in gymnastics, the image was as stirring as Bob Beamon’s historic Olympic long jump or the U.S. hockey team’s upset victory over the Soviet Union.

And then there are times when he is simply frightening. This is the Karolyi the public often does not see—a gloomy, glowering figure who hulks about his gym, lashing out at his students for the tiniest of imperfections. Bela Karolyi is the most disliked figure in competitive gymnastics. Other coaches claim that his golden touch is really a savage one, that for every successful gymnast he develops, he drives off half a dozen more. They see him as a tyrannical Svengali figure who calculatingly tries to wear down his top girls until only the two or three best ones are left standing. “Karolyi’s girls,” said one nationally respected coach, “don’t so much retire as expire.”

“I’ve seen so many of his girls who are just psychologically damaged,” added Debbie Kaitschuck, a rival Houston coach whose own nationally prominent program is filled with many talented girls who have left Karolyi’s program. “He has played so many mind games with them that they are in the gutter, convinced they can’t do anything.” One official from the United States Gymnastics Federation (USGF) said other coaches had complained to her that Karolyi’s long, strenuous workouts “physically drive a girl into the ground—and when she gets injured, he’s always ready with a new girl to put in her place.”

Although gymnastics has always had its share of politics, jealousy, and ancient personal grudges, the animosity toward Karolyi is startling. He has been labeled power hungry and publicity mad, so intent on keeping his legend alive that he allegedly recruits top gymnasts who are working with other coaches. The bitterness runs so deep that coaches and federation officials prevented him from being named the coach of the women’s U.S. Olympic gymnastics teams in 1984 and 1988, although many of the team members had been trained by him.

Even the parents of the girls who flourish in his program aren’t sure whether to praise or rebuke him. Erica Stokes’s mother recalled that in six years she had had maybe two or three conversations with Karolyi that lasted longer than a few minutes. “We are all Bela-ologists: We all try to figure out why he’s in a good mood one day and then furious the next,” said Kim Zmeskal’s mother, Clarice. “He is a very temperamental man who spends more time raising my child than my husband and I do. And, I have to say, that’s a little unnerving. I see him yelling at Kim, and I want to go through the roof.” Clarice Zmeskal paused. “But I can’t argue with his success.”

There, essentially, is the rub. The fact is, Bela Karolyi dominates the landscape of competitive gymnastics. In 29 years of coaching, he has produced 27 Olympians, 7 Olympic champions, and 15 world-title holders. Besides Mary Lou Retton, he created the beloved Romanian Nadia Comaneci, who in 1976 scored the first perfect ten in an Olympic gymnastics competition. Since Karolyi’s arrival in the U.S. in 1981, he has set new standards of performance that other American coaches have rarely been able to match.

“These critics of mine, who do you think they are?” asked Karolyi. “They are jealous coaches, nonproducers.” He chuckled triumphantly. “When they say, ‘Oh, that goddam Bela,’ it is because I have made their lives miserable. They now have to work as hard as me, all day long. They can’t come into a workout in a suit and tie and say, ‘Okay, girls, try very hard now and do fifteen minutes of conditioning while I leave early to play some golf.’ Those coaches, my friend, are finished.”

Indeed, Karolyi is now the Pied Piper to thousands of starry-eyed moppets. Each year, more than six hundred of them from around the country, some as young as two years old, arrive at Karolyi’s World Gymnastics, a couple of warehouse-size, prefabricated metal buildings in the bleached-out suburban expanse of North Houston. There, they work with one of eight assistant coaches, hoping that the Great One, watching somberly from a distance, will someday tap them for his elite team. “Little girls,” said Kathy Kelly, the program administrator of women’s gymnastics for the USGF, “always want to please the adult in charge. With Bela, they all want to please him, to win his affection. Frankly, they’ll do things for him they’d never do anywhere else.”

It was seven in the morning, the sun barely up, and Karolyi, striding like a man possessed, was headed to the elite team’s gym for another workout. “My attitude,” Bela Karolyi was saying, “is never to be satisfied, never enough, never. The girls, they must be little tigers, clawing, kicking, biting, roaring to the top. They stop for one minute—poof!—they are finished.”

The girls were already there, stretching their constantly sore bodies. When they awaken after a night’s sleep, they are like old women, their joints as stiff as boards. One of Karolyi’s homegrown stars, the peanut-size Hilary Grivich of Huntsville, can hear her ankles, knees, and back pop when she gets out of bed. A doctor once told her that she has the aches and pains of a forty-year-old woman. Hilary just turned fourteen last May.

“Okay, my leetle ones,” said Karolyi. “We have a good workout today, yes?”

For the next three hours—just as they do every morning—the gymnasts went through an astonishing workout. They ran around the floor for thirty minutes, sometimes turning to run backward, then sideways, then forward again, pumping their knees up as high as possible. They performed hundreds of sit-ups, push-ups, leg lifts, pull-ups on a bar, then more sit-ups hanging off a bar. And always there was Karolyi, missing nothing.

Twenty years ago, the great gymnasts came of age in their late teens and early twenties: elegant young women with swanlike necks and sleek, almost invisible muscles. The sport was more like an art form, closer to ballet. Today, the game belongs to a breed of wunderkinder who are less than five feet tall, weigh about eighty pounds, and perform like exploding firecrackers. They thunder down an 82-foot runway, blast off a springboard, vault over a leather horse, and still find time in midflight to execute a double back somersault with a full twist. The standards have changed so considerably that the best performers are those who are able to produce a variety of gravity-defying flips—always landing on both feet, without a wobble.

Much of that change, of course, is due to Karolyi himself. In the past decade, he has masterminded the rise of gutsy kids who produce spectacular bursts of energy in mere seconds. They perform whirling floor exercises, they attack the uneven bars with a barrage of multiple hand changes, and they frolic on the perilous four-inch-wide balance beam, springing up, twirling, then landing as delicately as a snowflake.

Although Karolyi’s gymnasts have no breasts or hips to speak of, they possess calf muscles the size of baseballs, thighs that an NFL running back would admire, and shoulder and back muscles that ripple every time they move. Even their bottoms have clearly defined muscles.

In addition—and this is strangely important—they have not reached puberty. While any other teenage girl prays for a fully developed figure, gymnasts see puberty as their enemy. At this level of competition, some girls say a bust line and a protruding pelvis are the very things that can physically slow them down and ruin their careers. They are on a race against time, to reach their peak before their bodies betray them. That is why a gymnast’s career can be mercilessly short. The best gymnasts start hitting their stride by fourteen; then abruptly, they announce their “retirement” at the wizened old age of seventeen or eighteen.

Though devoting one’s entire childhood for such a fleeting chance at adolescent glory seems absurd, that might be exactly why the sport captures the imagination. Women’s gymnastics has really become little girls’ gymnastics. It is filled with the flower of youth, with innocent munchkins in leotards leaping about as if they have helium in their legs. Women’s gymnastics has become the perfect television event: The girls, just the right size for the TV screen, look like porcelain dolls that move.

Not that anyone would find anything cute about one of Karolyi’s tediously repetitious workouts. As each gymnast goes through a routine, Karolyi barks at her in a clipped tone: “Keep your stomach. . . . Don’t block on the upswing. . . . Round it off. . . . Stretch on top.” Says the USGF’s Kathy Kelly, “There’s not a lot of stroking of the elites in his gym. There’s mostly criticism, and the phrase you hear him say most is ‘do it again.’ I know if someone asked my own daughter, who is a gymnast, to do that many routines in a row, she couldn’t cope.”

Karolyi also has little tolerance for injuries or illness. If a mother calls to say her daughter can’t work out because of a cold, Karolyi threatens to kick the girl off his team. Mary Lou Retton recalled attending a workout with a broken finger. Karolyi told her to perform her uneven bar routine. Because of the pain, she fell and landed on her chin. “I started bleeding from the mouth,” said Retton, “and as much as I tried not to, I started to cry. And Bela just got really mad at me. He said, ‘Get back on the bar.’ I was just gushing blood. I tried to get back on the bar. I couldn’t do it. So he said, ‘Okay, then get out of the gym! You’re through!’ ” Karolyi returned to the workout, and Mary Lou was taken to a hospital emergency room. She was back at the gym the next day.

To understand how Karolyi could act that way with young girls, it is important to remember that he is very much a product of the totalitarian athletic system of communist Romania. He might live like a free-wheeling capitalist—he splits his time between a 248-acre ranch and a large Houston home and takes in around $80,000 in annual fees from his gym and summer-camp programs—but he regularly complains about “weak American parents” creating “children without backbone.” He scoffs at American coaches who allow girls to take bathroom breaks and chew gum. He nods his head sadly when he hears that one of his rivals, the boyish Stormy Eaton of the Desert Devils Gymnastics Team in Arizona, takes his girls waterskiing during off days.

Karolyi refuses to speak with the girls about their personal lives. Like a dictator, he demands absolute submissiveness. “What do you think we are doing, working out in a cabaret? No. I am not their playmate. I take the emotional garbage off of them, the worthless goofing off, the crying scenes, spilling the Coca-Cola. We have our relaxing moments, but never in the gym.”

Growing up in Transylvania, the mountain country of Romania, Karolyi was put to work at an early age on the family farm. A strapping, powerful athlete, he became a top college discus and hammer thrower and never particularly cared about gymnastics until he flunked a college gymnastics course. Irate over his failure, he became obsessed with the sport, determined to prove himself.

He met and married a pretty blond Romanian gymnast named Martha. Together, in 1963, they began teaching physical education at a school in a small Romanian coal-mining town. Karolyi brought in a couple of old mattresses and began teaching the kids handstands and somersaults. Within a year, his students won a regional gymnastics meet. “I was not a technical coach,” he said, “but I knew the secret to gymnastics. It is, my friend, discipline. The man who can teach discipline, who can teach aggressiveness, this is the man who wins.”

A great gymnastics coach in Romania is treated like a national hero. The ambitious young Karolyi saw the sport as the place to make his mark. He and Martha moved to a larger city, where they were given their own gymnasium. Martha concentrated on the girls’ balance beam and floor-exercise routines. Bela focused on the vault and uneven bars (a system they follow to this day). They would scout kindergartens at recess, looking for the most athletic girls (Karolyi didn’t like coaching boys because, he said, they were restless, unfocused, and at that age, physically incapable of performing as well as girls). As a test, Karolyi had the girls sprint for fifteen meters and then walk on the balance beam; if they showed the slightest timidity on the beam, Karolyi sent them home.

It was at one kindergarten recess that he saw a slim, dark-eyed beauty. “Before I could reach her,” Karolyi recalled, “the bell rang. She disappeared with everyone else inside the school. My God, I was desperate. I went inside, going through each room, looking for this little girl.” He paused, melodramatically holding out his hands. It was impossible to tell if he was making this up as he went along, but one couldn’t help but be swept along by the power of his storytelling. “I would cry into each room, ‘Who loves gymnastics? Who loves gymnastics?’ And then, there she was, raising her hand in the back, saying, ‘I do. I do.’ The child was”—he paused again—“Nadia Comaneci.”

Karolyi drilled Nadia and her teammates, working them out five hours a day instead of the usual two and a half. He forced them to do strength exercises like weight training—unheard of for gymnastics in that day—and he ran them in the mountains. He told them what to eat and when to sleep. If a girl didn’t do what he said, he dismissed her. “She was just eliminated,” said Karolyi. “You were not good? Good-bye. If you goofed off once, you were out in two minutes. As a coach, I had no obligation to you. That was just the political system.” Regardless of Karolyi’s harsh rules, girls clamored to get in. It was an honor to be chosen for a government athletics program. Gymnastics—like basketball for some American kids—seemed to be the only way for little girls to break free of their dreary, commonplace socialist lives.

At the age of fourteen, Comaneci stunned the world at the 1976 Montreal Olympics with a repertoire of double somersaults and twists never before seen in competition. Karolyi, no stranger to self-promotion, relished the fame. On trips abroad, he would give blustery interviews to amused reporters about the way he produced champions. Meanwhile, government officials traveling with him would proclaim that it was the communist system producing champions. “What about my contributions?” Karolyi asked. “My God, it was like they forgot. They wanted all of the credit.”

When the Romanians lost the women’s team championship to the USSR in the 1980 Olympics, funding for Karolyi’s program was partially cut. He was livid. He raged that he was no longer appreciated. In 1981, on a trip to the United States with the women’s team, he got into another argument with Romanian officials and decided that he had had enough. With only $360 in their pockets, knowing just a few words of English, he and Martha remained in the U.S., even abandoning their seven-year-old daughter.

It was, in truth, the strangest of defections. Here was a man who defected not for any lofty principles of freedom over communism. He defected because he couldn’t run things the way he wanted to back home. He couldn’t be the all-controlling autocrat. He thus came to America to create his own empire.

To make a living, Karolyi swept the floors of a restaurant in Long Beach, California. He and Martha lived in a $7-a-night hotel room and learned English by watching Sesame Street. Their daughter soon joined them (she never seriously pursued gymnastics), and within six months, a friend from the University of Oklahoma hired him to work in summer gymnastics camps. In 1982 he moved to Houston—he had always wanted to come to Texas, he said, after seeing John Wayne cowboy movies—and began his own gymnastics program.

The famous Olympic coach tacked posters on trees in the neighborhood to announce the opening of Karolyi’s World Gymnastics. He could only hope that if he built a gym, they would come. And they did—Mary Lou from West Virginia, the wonderful black gymnast Dianne Durham from Indiana, Phoebe Mills from Illinois, who later would become the only U.S. gymnast to win a medal in the 1988 Olympics. The girls left their own families and lived with families in Houston. Those on the elite team would go to school only part-time or take correspondence courses so that their education would not interfere with Karolyi’s twice-daily workouts. They gave up slumber parties, Friday night football games, boys. They spent their summers at the gym on his ranch.

Many girls who pondered a move to Karolyi’s gym were told that he was a gymnastics version of Count Dracula, that he would starve and beat them. “My coach back in Illinois told me that I’d have to stay in Bela’s house, where he’d watch me day and night,” said Betty Okino, who had desperately wanted to become a Karolyi gymnast in her elementary school days after reading Nadia Comaneci’s autobiography. “He told me Bela would give me anorexia. Everything he said was pretty ridiculous—except for the part about Bela yelling.”

Intentionally, Karolyi plays the role of the hot-tempered father figure, never pleased, always looking for perfection, motivating through fear. It was an extraordinary motivational tool for ingenuous adolescents. “I know this sounds weird, but when he was real mad at me, it was kind of inspiring,” said Mary Lou Retton. “I was always trying to get him to smile over something I’d done.”

Although some labeled his techniques as cruel, others said Karolyi was exactly what American gymnastics needed. “In fairness to Bela,” said Muriel Grossfeld, the coach of the 1968 and 1972 women’s U.S. Olympic gymnastics teams, “learning gymnastics is such a hard task that you have to do everything in your day to make yourself better. Bela knows if a girl hasn’t pushed beyond her limits every day, she will never win.” It wasn’t until gymnastics meets that Karolyi would show his affection, lifting his victorious girl high above his head. Other coaches thought he was grandstanding, trying to get the attention of the television cameras. Karolyi, in response, would mock his competitors, announcing that he should be the coach of the U.S. national gymnastics teams because at least he knew what he was doing.

“You have to understand that a lot of these coaches had been working for years, working with girls around the clock, getting no publicity at all,” said Grossfeld. “Then, suddenly, parents started seeing Bela all over the television, and they said, ‘That’s the man who can take my daughter to the Olympics.’ So they showed up at the coach’s office the next day and announced they were moving to Houston.”

Coaches said that Karolyi was getting the credit for girls whom they had developed. They complained to the USGF that he was actively recruiting their girls. Karolyi denied all charges. “Girls came to me,” he said in his haughtiest voice, “because I am the best. I am sorry if this bothers the other poor coaches.”

If it is lonely at the top, it is simply because Karolyi likes it that way. “He thinks everyone is out to get him, he really does,” said University of Utah women’s gymnastics coach Greg Marsden. “He just doesn’t give a damn what people think of him. He has his own idea of what it takes to win, he has his own goals, and no one is going to get in his way.”

The problem, curiously enough, is that those who sometimes get in the way are Karolyi’s gymnasts themselves.

After the 1988 Olympics, Bela Karolyi began to build a new elite team to prepare for 1992. Among the younger girls working with his assistant coaches were some obvious candidates. The strong-legged Kim Zmeskal, a blond, blue-eyed Houston native, had been coming to Karolyi’s since the age of six, when her flabbergasted parents watched her turn cartwheels across the entire back yard, hang upside down from the jungle gym, and flip over the living room couch. There was also Erica Stokes, who had so impressed Karolyi when she left her family at the age of ten to train at his gym. And there was Chelle Stack, who had moved with her parents from Pennsylvania when she was only nine to be with Karolyi. An early bloomer, Chelle had been named to the 1988 Olympic team when she was just fifteen—the youngest member of the squad—and she wanted to try again.

Karolyi picked a few others, but the body count quickly soared. One of his best girls fell in the gym and injured her back. Another, whom Karolyi had ridden for laziness, finally quit after she came down with the Epstein-Barr virus. Never at a loss for talent, Karolyi had a ready supply of girls to take their places—such as Betty Okino, who arrived from Illinois.

In 1990, at the age of fourteen, Kim Zmeskal won the U.S. national championships; she repeated as champion this year. But others were faltering. Last spring, after Chelle Stack did poorly at a USA-Romania meet, Karolyi suggested that she move on to another gym. In part, Karolyi didn’t like her because she was nearly eighteen, she weighed 97 pounds, and she had not emerged from what Karolyi calls “the storm of puberty.” She wasn’t as emotionally directed; she was hesitant on the balance beam. “I told her there were no hard feelings,” an unmoved Karolyi remembered, “but please leave. She said, ‘I’m trying,’ and I said, ‘But you are not progressing. I can’t accept this.’ ”

Karolyi’s reaction should have been no surprise: In 1987, Kristie Phillips, who under Karolyi’s coaching had become the best gymnast in America, left under disputed circumstances after hitting puberty and gaining twenty pounds. Chelle moved to Debbie Kaitschuck’s gymnastics program in the Houston suburb of Cypress. Of the eight girls on Kaitschuck’s elite team, five are from Karolyi’s gym. The 35-year-old Kaitschuck, a former all-American college gymnast, said the girls still have the potential to compete internationally. “But they’re just traumatized by Karolyi’s drill-sergeant tactics. I have to spend a lot of time showing them some compassion and rebuilding their confidence. It’s amazing how parents get brainwashed into thinking Bela’s gym is good for their kids.”

Karolyi, meanwhile, relentlessly pushed toward the World Championships. For the first time, he was going to be the U.S. team coach at the event. If his girls could beat the Soviets, his place in gymnastics history would be assured. When summer arrived, he cranked up the tension even more. He knew that if his elite girls could endure a summer of his withering appraisals, they would have no trouble handling the pressure of the World Championships. He gave them uplifting speeches that would have made Vince Lombardi proud. “My leetle ones,” he said, his voice rising with each sentence, “every day will be a rocky road. Every day you are going to have to fight, because, listen to me, all over this world, right now, there are hungry, determined gymnasts working as many hours as you, thinking about you, wanting to destroy you!” The silent, wide-eyed girls looked as if they were being sent before a firing squad.

Away from the gym, in his cedar-log ranch home decorated with a John Wayne picture and trophies from his hunting trips, Karolyi can be the most pleasant of hosts. In his wine cellar, he drinks a Heineken and talks endlessly to a visitor about his “leetle ones.” Remarkably, while most American gymnastics coaches quit by Karolyi’s age of fifty, burned out from the stress of such intense work with children, Karolyi keeps going.

Something about the precisely choreographed environment of gymnastics lures Karolyi. Here is the one place where the human body can be fashioned to perform flawlessly, where a person’s mind and muscles can work as one. In some ways, gymnastics can be as absorbing as art. “It is like a goddam disease,” said Karolyi. “My God, you don’t know. It still wakes me up at night. How to get Kim to stretch on the bars? How to get Betty to move faster? I cannot get these thoughts out of my head. I am up at five in the morning, writing down notes on what I will do for them that day.”

Throughout the summer, Karolyi gave his girls little time to think about anything else but gymnastics. Between the morning and afternoon workouts, he would let them sunbathe by the swimming pool or watch Days of Our Lives back in their own cabin. A couple of Seventeen magazines were scattered about, the articles in them dealing with teenage romance and sex and peer pressure at school—issues that Karolyi’s kids, in their isolation, had little opportunity to experience. But there were no complaints. Although they slept with stuffed teddy bears in their bunkbeds, they were just as driven as any professional athlete—as driven as Bela himself.

“What scares me about quitting,” said Kim, “is that I’ll have to do regular teenage stuff. I think maybe I’ll get bored. I mean, there are lots of nights when we ask one another why we’re doing this, why we put up with Bela yelling at us.”

She chewed on a fingernail, thinking carefully. “But I know if he didn’t make us work so hard, we wouldn’t be so good. We wouldn’t have a chance to go to the Olympics. We wouldn’t get to be on TV and travel around the world and stuff.”

As Kim knows all too well, life with Karolyi can end with stunning swiftness. Throughout the summer, she and the others could see that Karolyi was cracking down unusually hard on their friend Erica. Even so, it was a shock when Karolyi stopped a workout and told Erica she was finished. Erica might not have been as good as Kim Zmeskal, but she remained one of the better competitors in the country. Why couldn’t Karolyi have kept working with her? Couldn’t he have shown a little loyalty to one of his most loyal students?

“I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand what makes Bela tick,” said Susan Stokes, Erica’s mother. “He is so committed to making these girls champions, but I have to wonder if he has any personal feeling for them at all. Does he care about them? Or does he do all this for his own fame? Sometimes I think this is just an ego, power thing for him. He doesn’t see little girls for who they are. He sees them as beautiful little machines that he can create and show off to the rest of the world.”

This past September, in front of 15,103 screaming fans at the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis, Kim Zmeskal battled it out with the USSR’s Svetlana Boguinskaia for the women’s all-around title at the World Gymnastics Championships.

Boguinskaia, the defending champion, was considered the favorite. But in the vault, Kim made her move. She gunned down the runway, her little legs a blur, banged onto the springboard, and after coming down a couple of somersaults later, found herself with a nearly perfect 9.962. Then, in her floor routine, she performed three back flips without using her hands, ending with a breathtaking double back flip.

The score came up 9.987, just enough to win. A delirious Karolyi was up and running. With both hands, he lifted Kim aloft. For the first time in history, an American woman had captured the all-around title at the World Championships.

Kim also won a bronze in the floor exercise; Betty Okino won a bronze in the balance beam. Though the Soviets again won the team title, the U.S. women’s team (composed of six girls, four of whom belonged to Karolyi) came in second, its highest finish ever. “This is one of my greatest moments in coaching,” Karolyi proclaimed at a packed press conference.

And Erica Stokes? Vowing to prove herself—to show Karolyi that he had made a mistake—she and her mother had moved to Oklahoma City, where Erica was working out at Dynamo Gymnastics, a prominent program run by Steve Nunno, a former Karolyi assistant who is now one of Karolyi’s biggest rivals. Already she had lost ten pounds and learned more than half a dozen new skills. “The fire is back in her eyes,” said Nunno. “I think, come Olympic time, you’re going to see great performances by her.”

But if Erica’s return to another gym bothered Karolyi, he didn’t show it. He had other things on his mind. Only one week after the World Championships, his girls were back in the gym, ready to start all over again.

“Okay, my leetle ones,” said Bela Karolyi. “We have a good workout today, yes?”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Huntsville