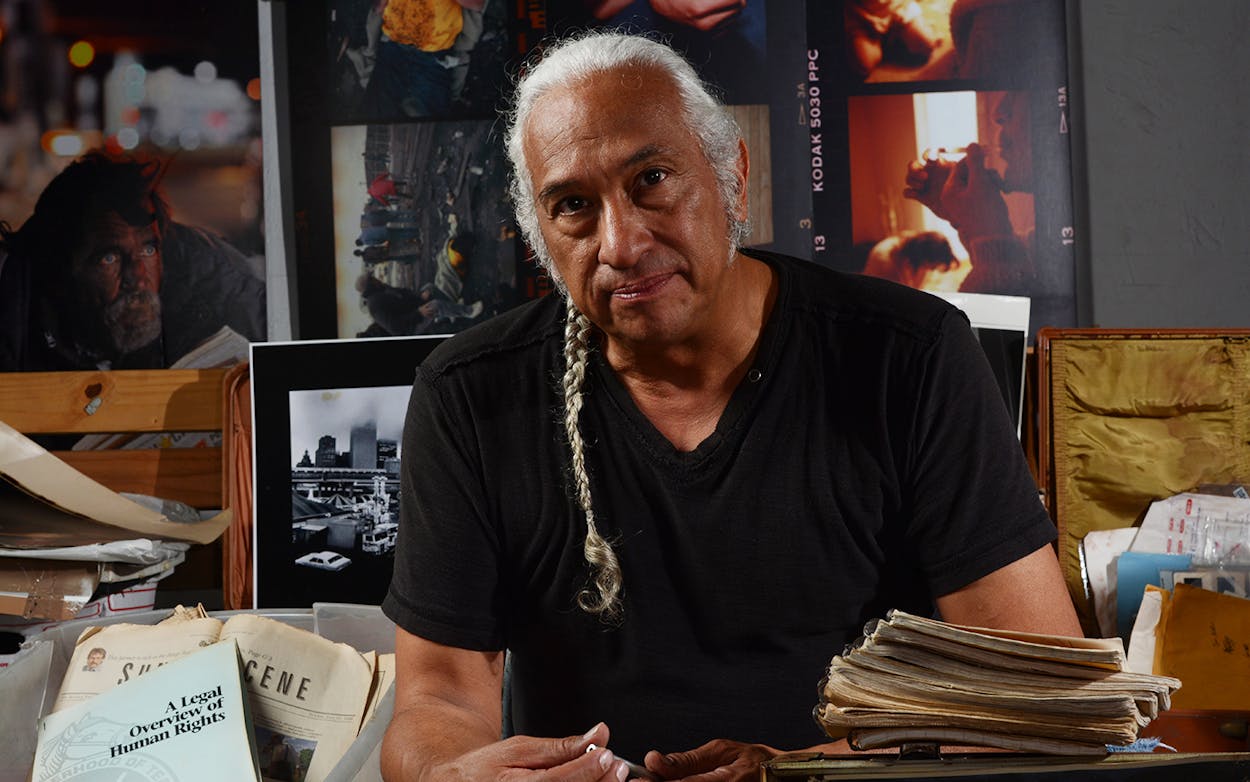

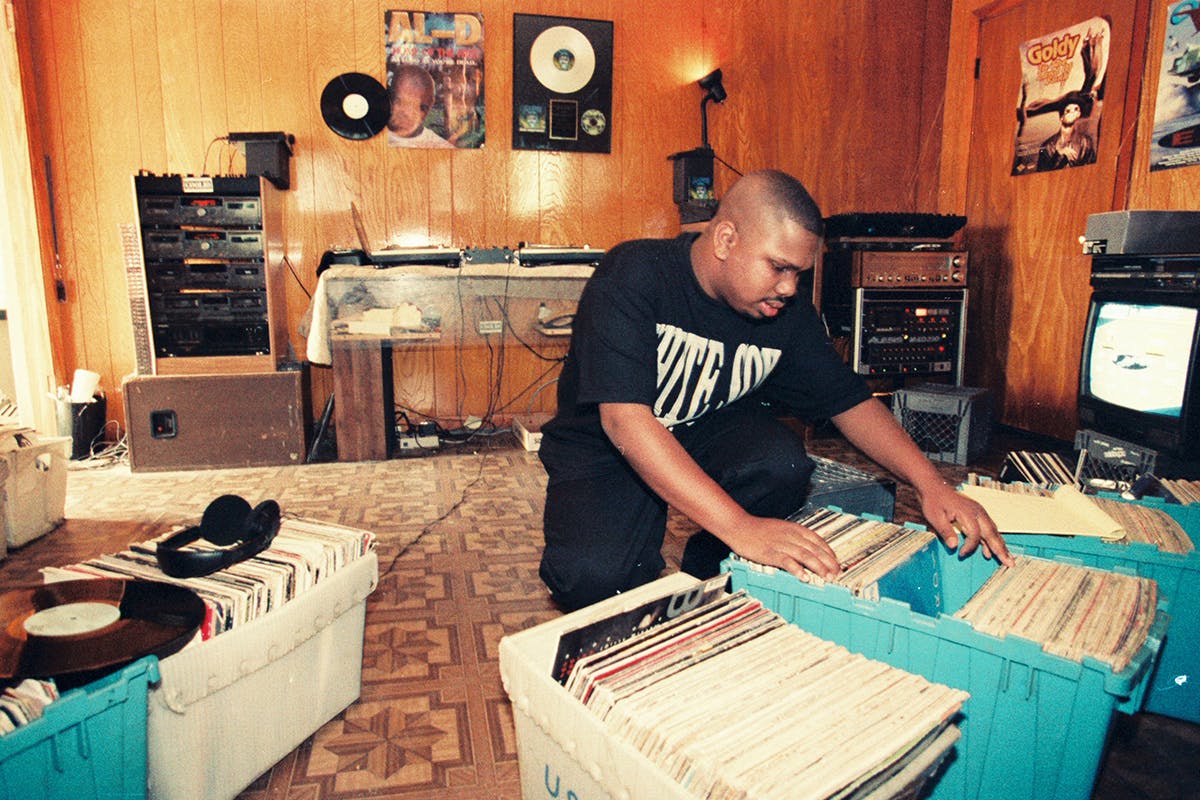

For 25 years, Ben Tecumseh DeSoto worked as a resident staff photographer at the Houston Chronicle. Documenting the results of public policy on homelessness and poverty is what the longtime Texan calls his life’s work. But the 61-year-old photojournalist is perhaps best known for the way he captured the energy and excitement of hip-hop and punk scenes as they unfolded in Houston in the eighties and nineties; through his camera lens, he documented the rise of local stalwarts including Geto Boys and DJ Screw.

In recent years, DeSoto has been accounting for his own life and work. The University of Houston Libraries Special Collections acquired his archive in 2018, and a new documentary directed by Andrew Benavides and Michael Witnes Zapata, Ben DeSoto: For Art’s Sake, is screening this weekend (at the African American Library at the Gregory School on Saturday, and Sunday at the Houston Cinema Arts Festival). DeSoto spoke with Texas Monthly about building an archive, how the film came about, and his work documenting Houston over the years.

Texas Monthly: What was it like to grow up in Pasadena?

Ben DeSoto: I grew up near Satsuma Park. Somehow or another, all the Mexicans ended up in a little five to six block area near the park. My family was a generation removed from Huntsville.

TM: You’ve spoken before about trying to cover a story, as one of your first jobs in photojournalism, that involved the KKK in Pasadena. What happened?

BD: So, I’m working at the Pasadena Citizen part time on weekends. And the klansmen had a rally on city property. And I show up [to shoot and report] and they say: “I’m sorry son, I’m not sure what you are, but you’re not white.” And they wouldn’t let me in. I took some pictures, and I wrote a little something about getting shut out. And very informally, the mayor and city councilman all personally apologized to me…and the klan closed their bookstore about a year later. I think they were confronted with the reality of discriminating against someone.

TM: You finished up college at the University of Houston’s photojournalism program and landed at the Houston Post, where you had previously been an intern. What was your life like when you started working as a photographer in Houston?

BD: I started at the Houston Chronicle at 23, the Houston Post at 22. In 1984, I was working the night shift at the Houston Chronicle from 3 p.m. until 11:30 p.m. I was the last one out, and the only people who were up were urban animals and punk band members. I really embraced and enjoyed the punk rock life and crowd and scene.

I was a fan like everyone else, and I wanted to photograph these bands. I started at the Island [the punk club] from the summer of 1980 until it closed in 1981. I dragged in lights and set them up in the ceiling. I had enough experience to know that if I used light stands, they would get knocked down. The place was a firetrap, anyway. And I say that with all the love you can have for a firetrap.

I had been photographing there probably a dozen times in that year when Mydolls shared the bill with Butthole Surfers and Stick Men With Ray Guns. There’s that iconic shot with incredible lighting of [lead singer] Bobby Soxx from Stick Men with Ray Guns dropping his pants and sticking the microphone up his crack. I had a few lights rigged up in there, one for the stage and then the other one was aimed out toward the crowd.

TM: Can you talk about the urgency in completing your photo archives?

BD: In 2016, I had some health issues. I was a working artist, and I was really challenged to complete a documentary work on poverty solutions—a cumulative of 30 years of work, including [documenting] the lives of two homeless people. One of my primary subjects, Ben White, passed away before my eyes. So what I thought was a happy ending turned into a document about a guy who has lived his entire life on the streets, to die five days after surgery for a tumor.

TM: How did the documentary about your life, Ben DeSoto: For Art’s Sake, come about?

BD: [The filmmakers] wanted to talk about the DJ Screw pictures. They actually caught up with me during Houston’s annual art crawl, when I was presenting my work on the “Understanding Poverty” project. By the time they finished the first interview, they knew they had something more. While I talked about my DJ Screw pictures, I was standing around all my street photography work.

My family has problems with Alzheimer’s, and I wasn’t very good in my self-care. And it reached a point of crisis. I was really fortunate to have my work in archives and have Andrew [Benavides] and Witnes [Michael Zapata] show up and document this. Because without them it would have been a little blip of a working archive. I was real fortunate that the timing was such that I was able to get all my archives into the University of Houston and the African American Library at the Gregory School. I had been working on that for some five years.

TM: The documentary details your work in music, but you also did so much with photographing daily life in Houston.

BD: Well, I was shooting pictures in the Fourth and Fifth Wards like that picture of [rapper] Scarface in the 1990s, hanging out with the Geto Boys and doing that [DJ Screw] stuff for Rap Pages. To cover assignments, a couple of times I would cut through the neighborhoods; they were my beat. I have extensive street photography showing the cultural blowback from the war on drugs that was aimed at the black community. I felt like my presence there was needed. Shooting in the neighborhood seemed like the natural thing to do.

TM: What are the symbols on your hands that appear throughout the film?

BD: I’ve been in recovery, and kind of taking care of myself. Someone gifted me a book on Reiki. It’s a healing technique, and one of things that the practitioners do is that they would draw power symbols on their hands before they start a healing session. I inscribed these tattoos on my palms back in 1980 when I started this work [covering homelessness and poverty]. I had to do something to express that I was recognizing I was stepping into someone else’s trauma.

[He points to his right hand, which has a pyramid with an eye inside]. The ojo de dios, the eye of God, the eye in the pyramid—this hand that takes the picture, and I hope to do no harm. And then this infinity symbol [points to his other palm], it’s a sign about the value of life. And what I’m photographing is merely a document of the current sin of neglect, abandonment, and despair.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- DJ Screw

- Houston