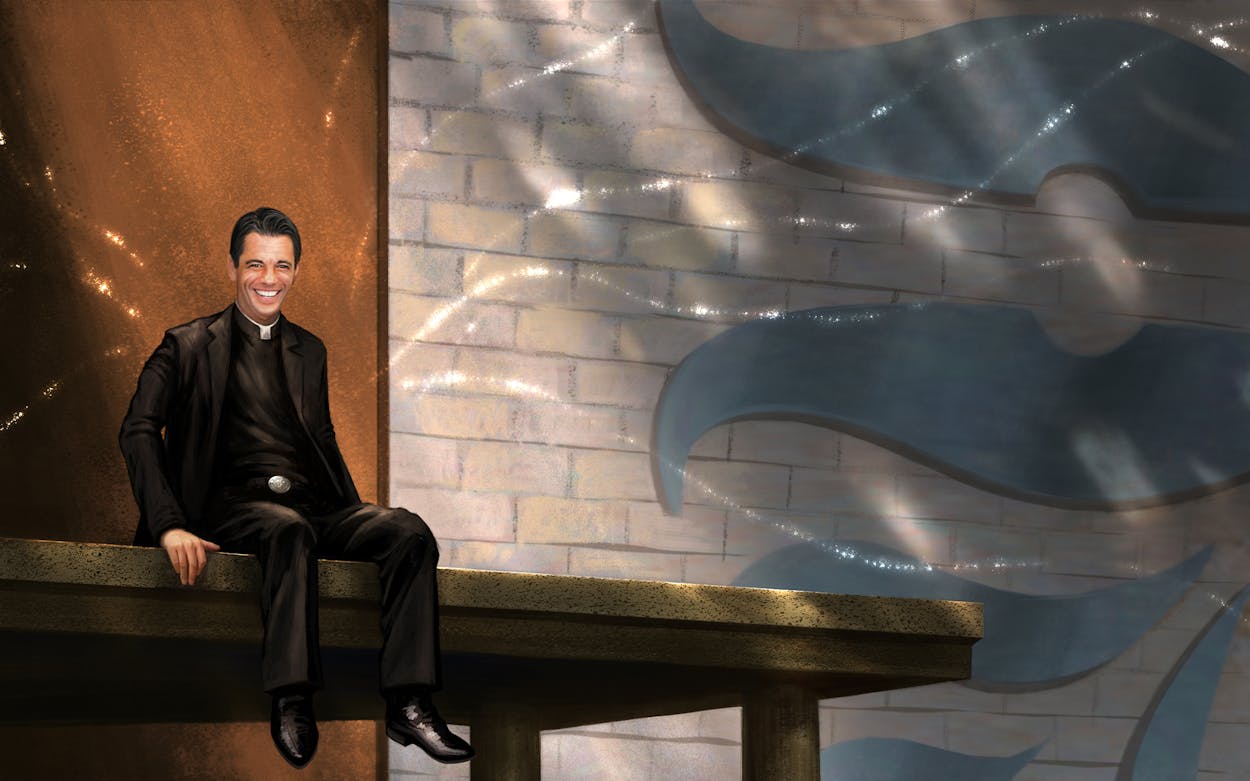

Though cancer rendered him skeletal in the last few months of his life, the high-voltage smile of Father Antonio “T.J.” Martinez could not be dimmed. Though feeble and in pain, he remained the same old beaming Father T.J., drawing laughs from the altar during his homilies and making the rounds at Cristo Rey Jesuit College Prep in Houston, which he founded with the mission of bringing rigorous academic opportunities to some of Houston’s poorest young men and women.

For just as long as he was able, the Brownsville-bred priest walked the halls of CRJ, his big silver rodeo belt buckle glittering against his black robes, an ever-changing gelled hairstyle crowning his head, his trademark cowboy boots clomping on the tiles. Students called him el Padre con botas, the priest who wears boots.

Even among other priests who have helped open private schools expressly for the poor, all of Cristo Rey’s 32 schools across the U.S. only admit students at or below the poverty line, Martinez stood out as a rock star. Thanks to his efforts in getting CRJ-Houston off the ground, in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI dubbed him a member of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre—a papal knight, in layman’s terms. In 2014, the Houston Chronicle named him “Houstonian of the Year,” the first time in history that award has been bestowed posthumously.

All that in just 44 years on earth.

“What we all remember most about him is his smile and his laugh,” says David Warden, a longtime friend, and the co-author of Miracle in Motion, Martinez’s literary “last will and testament,” a compendium of spiritual advice not just to the impoverished young men and women who attended Cristo Rey, but also the corporate high-flyers who comprise the school’s donors and community partners.

Warden, who calls Martinez “equal parts friend, hero, and saint” was there when the priest started the book, and had the honor of finishing it for him after the priest became too ill to write.

“The message of his book, for his kids or anyone else who wants to read it, is to follow your passion, but bear in mind that life doesn’t always follow a straight path,” Warden says.

Son of a prominent attorney, Antonio Martinez was raised in Brownsville, where he graduated from St. Joseph Academy. During undergrad at Boston College, he began to feel a calling toward Jesuit priesthood. “The Jesuits reignited the idea of heading out and doing good,” he told UT Law magazine. “That caught my imagination. The Jesuits are known as the soldiers for Christ and the vanguard of the Church. That spoke to my faith and my sense of adventure.”

There was a snag. He felt an equally strong obligation to follow his father into law, and so he did, at least for a little while. After spending a year volunteering in the Bronx, Martinez and his younger brother, Trey, entered law school at the same time. During his second year of law school, that priestly calling only grew stronger and stronger for Martinez. Bound by familial duty, he finished up anyway, and then passed the bar. So did Trey, which gave Martinez his chance: Trey would carry on the family tradition, and Martinez was free to heed the call. In 1996, ten days after he passed the bar, he took his initial vows in the Jesuit Seminary in Grand Coteau, Louisiana.

It can take anywhere from eight to sixteen years to become a fully-ordained Jesuit priest, and Martinez attained it in twelve. In the meantime, he’d received a Master of Arts in Chicago and taught at Dallas’s Jesuit College Prep for three years, beefed up on his theology at the Weston School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and racked up a Masters of Education at Harvard, across town, given the Valedictory speech, to boot.

By then he was ready for his final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and around that time he got a phone call from his soon-to-be-boss, Father Fred Kammer, SJ, provincial of the Jesuit Fathers in the South. Father Kammer told Martinez that they were looking for someone just like him to open a Cristo Rey school in Houston. Someone young, Spanish-speaking, energetic. Martinez was thunderstruck. He had no experience, he said, and what was being asked of him was simply too much. He begged for something, anything other than that.

A few days later Father Kammer rang Martinez again. “You know, I’d really like you to get that school in Houston off the ground,” he said. Again, Martinez pleaded for almost any other assignment.

And then there was a third call, which Martinez detailed in Miracle in Motion: “‘Congratulations, you are the founding president of Cristo Rey Jesuit.’ I thought to myself, ‘So this is how the vow of obedience works.’”

“He never got the assignments he wanted,” Warden chuckles. “But he told the ones he got were always better than what he wanted.”

The Jesuits have a few catchphrases unique to the order, not generally used in other strains of Catholicism. Chief among them is Ad maiorem Dei gloriam, the official Jesuit motto, meaning “For the greater glory of God.” The self-explanatory but deceptively profound “Finding God in all things” is another, and when you are a student in a Jesuit school, you are urged almost daily, perhaps several times a day, to strive to become “A man or woman for others.”

Martinez was very fond of uplifting his young and hungry and newly hopeful flock with another: “Set the world on fire!”

“I knew from the moment I first saw him that he would be something else,” says Andres Salgado, a member of CRJ’s first graduating class who went on to study computer science at Rice. “He took a hot gymnasium full of awkward teenagers reluctant to be there, and gave one of many fiery speeches that I would have the privilege to hear. Little did I know that this small man would become such a large part of who I am today. As many people have said, he was, and still is, larger than life.”

But before he could start getting his students to set the world on fire, he had to do so himself. When he arrived in Houston in June of 2008, he had limited funding, no building, no employees, zero students, and a deadline of two years to create this whole little world from scratch. He knew nobody in Houston and had never persuaded anyone to part with so much as a dime, which would become a key part of his job.

“There is never a good time to start a school for economically disadvantaged children, so why not now?” he told UT Law, in 2010, a year after Cristo Rey opened its doors a full year ahead of schedule. “I have to answer to God, and I’d rather start now than wait.”

He did have land — part of the campus of the shuttered Mount Carmel High School, on whose bones the new building now stands. Warden says that the old school was ripped apart down to the studs on the inside and the exterior totally rebuilt, thanks in large part to a $1 million donation from Houston’s Kinder Foundation. And with Martinez’s charm and persuasion having done its work, up the building went, with an initial class of 77 freshmen.

Under Martinez’s direction the school grew and grew, with each entering class a little bit larger than the last, and now overall enrollment tops 500. All the while, his health was failing. He received his diagnosis of stage four stomach cancer eight months before he died in late November 2014. Knowing his race was nearly run, Martinez was desperate to leave behind something even more substantial than the school and the hundreds of students he had inspired, and as a man who had taken a vow of poverty, his wisdom was all he could leave the world.

Martinez and Warden were having a glass of wine one night, and the priest asked his friend a question. The chemo treatments were not going to save his life, only prolong it, he said, and they made him feel too sick to accomplish much of anything. Should he quit that regimen? Should he exchange a few weeks of miserable life for the last few weeks of action he had left in him?

Warden told him he thought that was a good idea. Martinez agreed.

The first thing Martinez wanted to do was write a letter to his students, and anybody else who wanted to read it, about his life, the lessons he learned, and those that he could teach.

“By the second glass of wine, it had turned into a book,” laughs Warden. Knowing time was running out, they tore into that book’s writing, outlining each chapter, fully completing the first and last of them, compiling interviews, until at last Martinez could work no more.

Warden recalls one of the last times he ever saw his friend. By that time he’d already been in hospice care for a week, fading fast, with his friends and family at his bedside. In a lucid moment, Martinez heard that one his heroes, Archbishop Emeritus Joseph Fiorenza, wanted to pay his final respects.

“T.J. welcomed the opportunity with his huge smile,” Warden remembers, in a written reminiscence. “Before the Archbishop arrived, T.J. had insisted on getting dressed in his full Roman collar as a proper priest. His brother Trey helped him do that and then lay him back in bed. When he arrived, the Archbishop was left alone for a while to chat, and T.J. was clearly near the end of his life, in and out of consciousness. The Archbishop later commented: ‘My God, the man is dying and he got dressed just to receive me. I told him that was not necessary.’ But T.J. knew it was necessary, and had replied: ‘It was the right thing for a young priest to do.’”

“T.J. was like that,” Warden continued in his reminiscence. “Anything he did, he wanted to do right. Maybe that is his legacy. He showed us how to live a full life, as though each day might be our last, and then he showed us how to die with dignity and purpose, and without any fear.”

Warden also says that Martinez had a magical way of tricking people into becoming far better than they were before they met him. “T.J. changed many lives for the better. His reach was well beyond the marginalized kids he championed, to the CEOs and community leaders and corporations he enticed to help provide his kids a hand up to a better life through education.”

Warden points out the case of Paul Posoli. Before meeting Martinez, he was a hard-charging, high-flying type-A, downtown Houston energy trader, a man of faith certainly, but perhaps not first and foremost.

“Father T.J. asked him to become interim president of Cristo Rey,” Warden says. “And he is still the president of Cristo Rey, years later.”

His successor more or less got the job the same way he did – he didn’t think he wanted it, but he found he needed it. The same crooked path that led St. Ignatius from soldier to priest—that conveyed Martinez from lawyer to priest—had worked on Posoli.

The chain-of-command question settled, and all of the wisdom he could convey in Warden’s hands, and knowing his book would be forthcoming, Martinez sent out a short message to his students, former and current: “You guys are my pride and joy,” Martinez told his students. “You are the highlight of my life, and I will live and die with my favorite story being you and this school.”

Even through his grief, Cristo Rey graduate Andres Salgado knew that the last thing Martinez would have wanted would have been to have him sitting around moping. That was not what he was about, in life nor death.

“Now it’s time to go and set the world on fire,” Salgado says. “¡Viva el Padre Martínez! ¡Viva el Padre con Botas!”

- More About:

- Books