Even in these last weeks of 2021, the year still has an indeterminate feeling about it. In many ways, it began as an ugly coda to 2020: The COVID-19 pandemic was still unchecked by vaccines, which finally became widely available around March and April. The 2020 election didn’t feel over and done with, especially after the insurrection of January 6, an encapsulation of the Trump era with its combination of farce and violence. And then, of course, there was the deadly statewide freeze and grid failure in February.

Yet, by the summer, it didn’t seem things were all that bad. As more jabs were administered, cultural venues, including art museums and galleries, reopened. The public, including hundreds of thousands of new Texans, flush with cash, seemed eager to reenter the world and reengage with art. The Texas Biennial returned, as did local art events across the state that were canceled the previous year. And yet, 2021 is ending on a note of trepidation as another coronavirus variant spreads.

So what to make of all this? What makes 2021 strange is that there doesn’t seem to be a widely shared mood. There are plenty of valid reasons to feel optimistic, pessimistic, exuberant, exhausted, content, anxious, or some tangled combination of the above. By turning to art, perhaps we can help clarify, if only to ourselves, what 2021 was all about.

Below is a brief email conversation (lightly edited for clarity and length) among Texas Monthly contributors Michael Agresta, Molly Glentzer, and Rainey Knudson on works of art they felt captured something essential about the year, and on forthcoming 2022 shows they’re excited to see. —Josh Alvarez, arts and entertainment editor

Michael Agresta: The one work I saw in 2021 that, for me, most poignantly evoked what we’ve all been going through was Anri Sala’s Time No Longer video and sound installation in the Buffalo Bayou Park Cistern in Houston. I saw it in March, in what was still for most the pre-vaccine phase of the pandemic, at the end of a long, dark winter, especially for the older and more-at-risk. Sala’s image of a phonograph floating in an abandoned space station, in the aftermath of some unspecified disaster, the stylus now and then connecting with the record to play a beautiful quartet piece by the composer Olivier Messiaen, just spoke to me emotionally. (The installation was meant in part as a tribute to African American astronaut and saxophonist Ronald McNair, who died in the Challenger explosion.)

At that point I had felt so isolated from friends, family outside my household, and community life, and the future felt so clouded. Sala just captured that feeling, and he used this amazing underground public space filled with water to such incredible effect. I was floored.

Of course, what the pandemic means has changed since then, and 2021 thankfully had other chapters with different moods. Still, what a knockout in terms of delivering a timely, complex work under very difficult circumstances.

Molly Glentzer: I agree with you, Michael. Time No Longer profoundly affected me when I saw it in March, and it has stayed with me all year. I hope to visit one more time; it has been extended through January 17, 2022. I don’t know if visitors who walk in cold, without having read about the McNair background or the history of the abstracted Messiaen score, will understand all of the references. But that doesn’t matter.

Sala’s masterpiece also made me happy because it achieved the full potential of the cistern, which is a devilishly challenging environment. It’s an immense space, equal to 1.5 football fields but interrupted by 221 concrete columns that rise from its watery floor. It has a seventeen-second echo, it’s dark as all get-out, and visitors must follow a perimeter walkway. Previous installations by Magdalena Fernández (2017’s Rain) and Carlos Cruz-Diez (2018’s Spatial Chromointerference) were technically dazzling, but Time No Longer has a soul.

I very rarely experience what people call the sublime when looking at art, but it happened this summer in a place I least expected, within the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s meditative and too-short-lived show “Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock.” I was new to the work of Amaral, an 89-year-old Colombian textile artist known for her radical experiments with fibers (and other materials), color, and form. Think sculpture more than tapestries, or some hybrid of the two. Stillness 5, a hanging screen of black wool and horsehair, was the first stunner. Light bounced through and across it so that it appeared to ripple; I could have been watching a river flow. A large gallery of works covered in gold leaf felt as transcendent as a cathedral. For a while, I completely forgot the pandemic, and it was heavenly.

Rainey Knudson: I feel like I’m bringing a kazoo to y’all’s symphony, because a work that struck me was Houston artist Emily Peacock’s Funny Bone: I Don’t Feel It ’Til It Hurts, which is a life-size cast of the artist’s bent elbow that strongly resembles a butt. I mention this piece for a few reasons: first, it’s funny, and we are back in one of those dreary periods when art isn’t allowed to be funny (or at least isn’t rewarded for being so). Second, the implicit idiom of “not knowing your ass from your elbow” rings true—I feel like we are all part of the not knowing these days, and the artist seems to include herself in the carnival of ignorance. We’re all going through this confusing time together, which is what this elegant little white sculpture says to me. Which leads me to the third reason: it’s a remarkably beautiful piece. Funny, insightful, beautiful: an art trifecta that’s hard to beat.

MG: LOL, Rainey! A kazoo band would be right on key for so much of what transpired across Texas this year in the realms of, oh, voting rights, women’s rights, and the political polarization of public health. Gosh, we needed art escapes more than ever, funny or not.

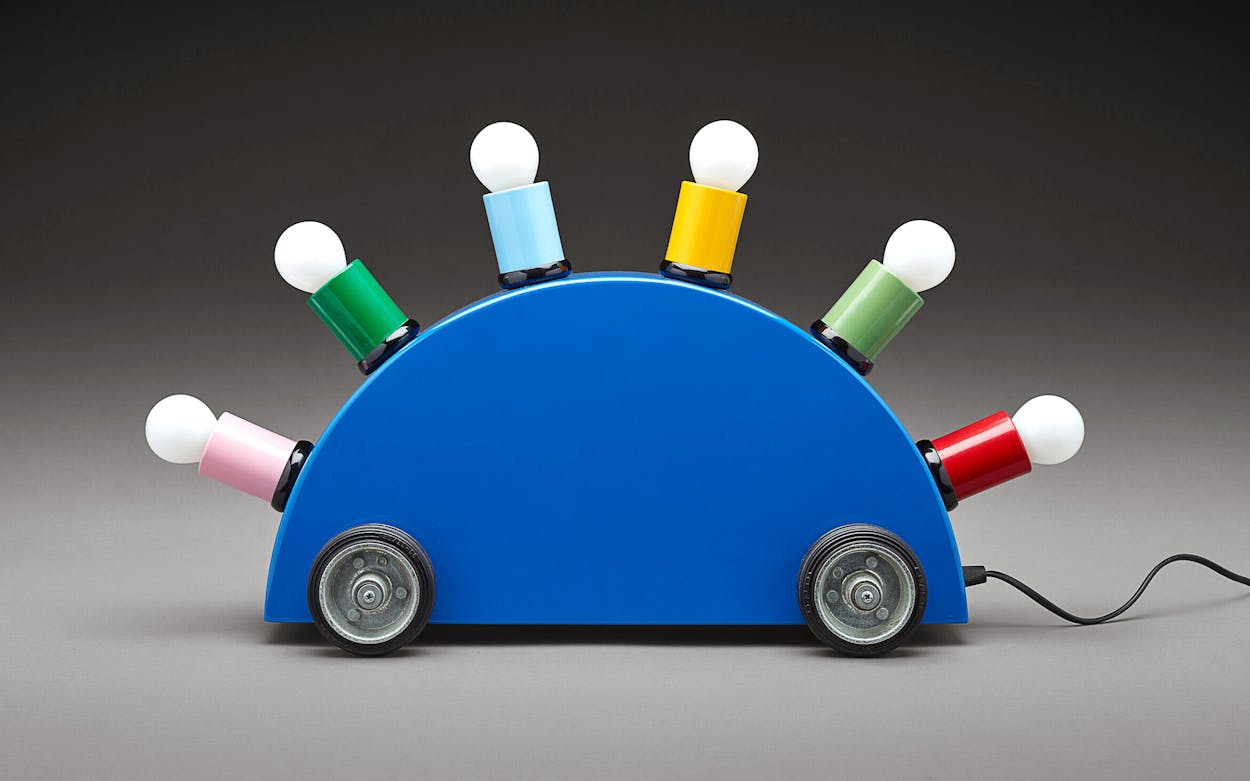

A couple of the memorable exhibitions in Houston did have some levity going for them. At the MFAH, David Hockney’s jaunty May Blossom on the Roman Road, one of the delirious canvases of “Hockney–Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature,” was landscape as cartoon, with shadowy plants as bogeymen. At about the same time, I fell inexplicably in like with Martine Bedin’s whimsical Super Lamp—a bright blue half circle with wheels and a “ray” of small bulbs atop multicolored cylinders. I first saw it in the MFAH’s elegantly uplifting “Electrifying Design” show. The shape makes me think “Volkswagen bug as sun on the horizon.”

And then, in a class by themselves over at the Menil Collection, came Niki de Saint Phalle’s audaciously playful yet domineering Nana sculptures. (Anybody want to start a campaign to replace the Goddess of Liberty atop the state capitol with one of these ladies?)

Good humor also showed its face more slyly in places I didn’t expect it. I’m talking more about sensory delights than laughs here—the charge you can get from immersing yourself in galleries full of works that just kind of hum with inventiveness. “The Dirty South” at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, an exhibition people will reference for years, has that. Yes, much of the show is thematically heavy-hitting, but it’s also brilliantly paced, like a good album. And try not smiling at the outrageous outfit from a 2015 CeeLo Green performance on The X Factor—a coat and pants covered in a fur of pink, green, yellow, and white daisies. (Hockney, eat your heart out.)

MA: I don’t think this pick counts as funny, but if we’re talking about the most joyful, affirming art we saw in an otherwise frustrating year, my mind goes to Carlos Ramirez’s Altar to a Dream public sculpture in downtown Dallas this spring. Ramirez is California-based, but his parents immigrated to the Rio Grande Valley as teenagers and spent years driving around Texas and nearby states as migrant farmworkers. Altar to a Dream is a painted, decorated 1951 Studebaker surrounded by memorabilia reminiscent of Ramirez’s childhood years on the road. There are symbolic references to episodes of economic and racial oppression, but on the whole the piece gives off warm nostalgia and the sense of a family somehow making it through together, in tight quarters, with a lot of love, against all odds—which had obvious resonances for many of us in 2021. The piece also built on Houston’s fun, goofy art car tradition in an interesting way, I thought.

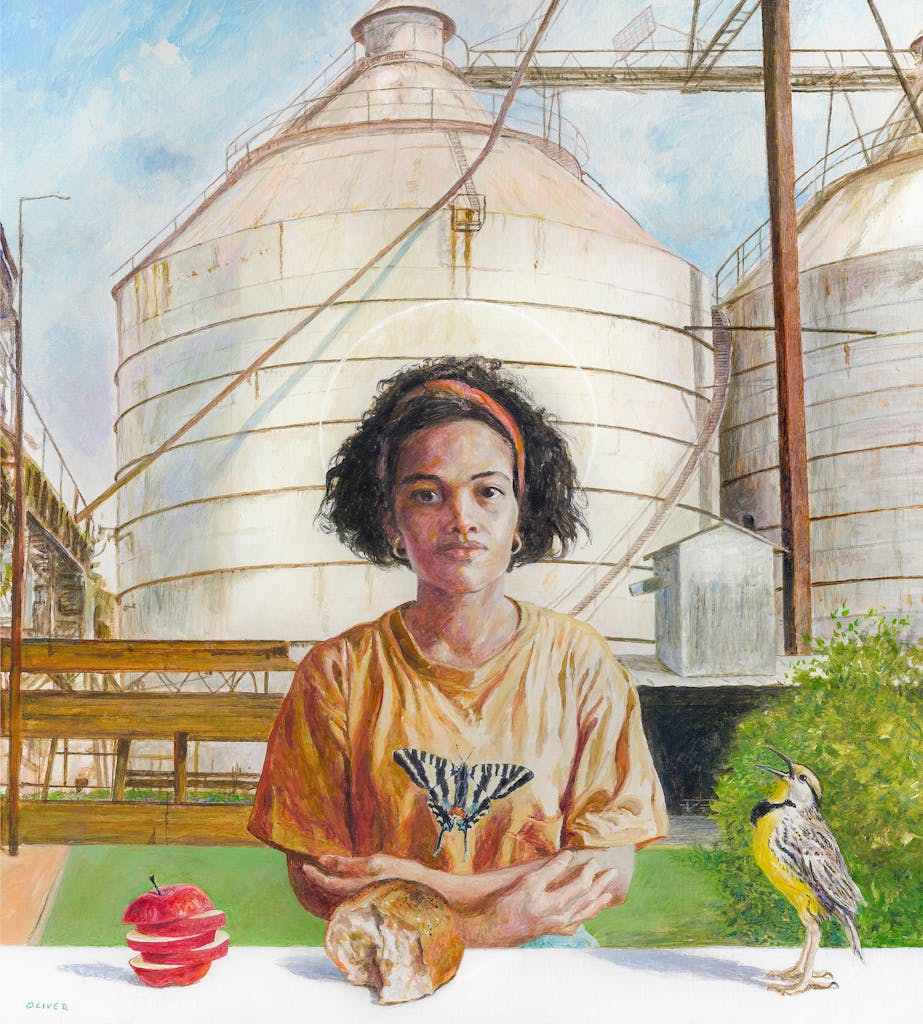

I’m curious what we’re all excited about for 2022. Any exciting developments on the Texas art horizon from where y’all stand? My answer to that is perhaps a small thing, but I thought it was very cool that I got to attend an absolutely top-notch art exhibition in Waco this October. The show, featuring paintings by reclusive mailman/genius painter Kermit Oliver, has been extended through Jan 22, 2022 at Art Center Waco. A lot of Texas cities are booming right now, not just the biggest ones, so it’s fun to see a town like Waco start to put itself on the map, artwise.

RK: Kermit Oliver is wonderful. I’m glad for the reminder to see that show in Waco.

As for me, the show I’m probably most looking forward to is Lynda Benglis at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, opening in May. Benglis is a genius with materials, and the show will focus on new and recent work, including her wonderful, meaty wall works covered with glitter. Some readers might be familiar with the Benglis in the permanent collection at the Fort Worth Modern—a wonderful, dark gray, blobby corner piece from 1970 titled For Carl Andre. Her work is rough-and-tumble and super energetic. I can’t wait.

MG: I am hopelessly and unrealistically ambitious: I want to see everything!

But if I have to choose . . . I am jazzed about the prospect of geeking out with “Soundwaves: Experimental Strategies in Art + Music,” which opens at Rice University’s Moody Center for the Arts in January. It will combine sculpture, audio, video, painting, and performance, and it will feature a bunch of artists whose work I love (Anri Sala alert, Michael!), plus some I am looking forward to learning more about. Nevin Aladağ, Nick Cave, Raven Chacon, Charles Gaines, Jennie C. Jones, Idris Khan, Christine Sun Kim, Jason Moran, Sarah Morris, and Trevor Paglen also are on the list. And Jamal Cyrus, Spencer Finch (whose lighting installation hangs at the MFAH’s Cafe Leonelli), and Jorinde Voigt are creating new works for it.

It’s also a FotoFest year, although the big Houston biennial—which has always been in March and April and takes over spaces across the city—is moving to the fall. What I don’t expect to change is the serious engagement with social, political, and cultural issues through the lens of any medium that classifies as “contemporary image production” at the big headquarters show—territory that’s always a fun dive. Amy Sadao, who joins FotoFest’s Steven Evans and Max Fields as a cocurator for this biennial, will likely bring some community activism into it. I don’t think they’ve yet come up with a more specific theme, but they are promising to feature “artists, photographers, and activists from around the globe who examine various modes of image-making, from social media and computer-generated renderings to news media and surveillance technologies.”

And . . . no matter what we’re seeing, wouldn’t it be nice if the pandemic were under control enough sometime in 2022 that we could see it without wearing masks? I’m not griping; art spaces have felt like some of the safest places to be in the past year. Just sayin’.