When Austin filmmaker David Modigliani began shooting a documentary about Beto O’Rourke in November 2017, the El Paso congressman and U.S. Senate candidate was still little known throughout much of Texas and was a long way off from erupting on the national stage. By the time Modigliani shot his last footage on election night of 2018, O’Rourke was one of the biggest stars in the Democratic party and would soon become a candidate for President of the United States.

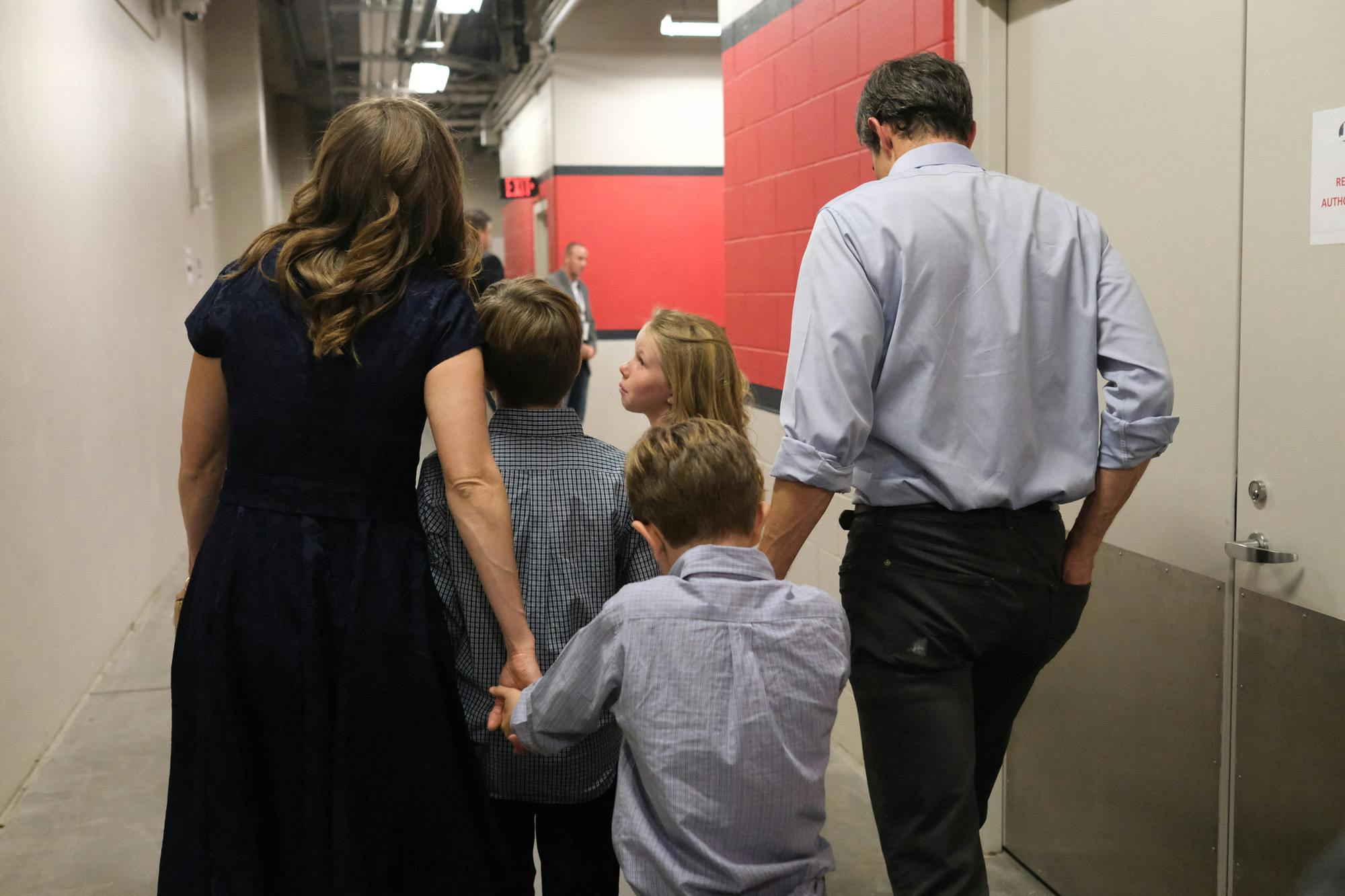

Modigliani modeled his film, Running with Beto, which premiered in March at SXSW in Austin, in part after D.A. Pennebaker’s famous 1967 documentary, Don’t Look Back, which captures Bob Dylan on a tour of the United Kingdom facing mega-fame for the first time. “I felt like Running with Beto in many ways was like following a rock band that hit it big but refused to change any of what had gotten them there,” Modigliani says. And the result is an intimate look at O’Rourke’s senate run from the inside—with testy moments with his staff, bittersweet interactions with the family he sees less and less of, and the intoxicating energy of the campaign trail.

Before the HBO debut of Running with Beto tonight (May 28 at 7 p.m. CT), Texas Monthly’s Eric Benson, who covered O’Rourke’s campaign for the podcast Underdog: Beto vs. Cruz, talked with Modigliani about the behind-the-scenes process of making a behind-the-scenes film.

Texas Monthly: You invested more than a year of your life into this project. How did you decide to make it?

David Modigliani: Well, like many great things in life, it comes back to baseball. I’m a founding member of the Texas Playboys Baseball Club, which is a sandlot baseball team here in Austin, and friends will form teams in other cities. The El Paso Diablitos came and played us in April of 2017 in Austin, and they had a lanky center fielder with a name I hadn’t heard before who happened to be a U.S. Congressman and he had announced that he was running for senate about six weeks before that.

During the seventh-inning stretch, he got up on a hay bale and brushed his sweaty locks aside in his dirty uniform and it was very clear, “Oh, this guy is incredibly magnetic.” But beyond that, it was like, when he described the type of campaign that he was going to run, that sounded like an odyssey that would be exciting to follow and would lend itself well to the structure of film.

TM: To make that kind of documentary, you had to get Beto and his campaign on board. How did you pitch him on it?

DM: I had the chance to have breakfast with him a couple of months later in Austin. I think in some ways, in a breakfast meeting, people’s minds are maybe a little less cluttered and maybe a little more open.

TM: Did he have concerns about opening up so much of his life to a camera?

DM: At the beginning I’m not sure he really knew what he was signing up for. And honestly, I think earning that trust came over time. I told him that we were going to need access that nobody else would have.

TM: He was campaigning nearly every day for almost two years. How often were you actually filming him?

DM: We started shooting in November of 2017. So we basically shot for the last twelve months. But we certainly were not filming every day. We tried to sort of capture a variety, I guess, so we tried to be in small towns and big cities. We were able to shoot some nine-person rallies and some 5,000-person rallies. We tried to be in, you know, all the corners of the state, and I think we were in the Valley nine times, went out to East Texas a couple of times, went to the Panhandle once, went out to West Texas a couple of times. We had 700 hours of footage, so there was a lot of good stuff.

TM: One thing that I’ve noticed in my time reporting on the campaign trail is you see a lot of the same things over and over again. Even with a guy like Beto, who doesn’t have a totally rehearsed stump speech, he’s saying a lot of the same things multiple times a day.

DM: I think part of it is about being around for some of the monotony, just waiting for the occasional happy accident. There’s this scene in the car where he’s really frustrated with the staff, where he’s talking about how he had to talk to all these reporters and not eat lunch and then they showed up late. He was like, “It’s hard for your brain to relax and unclench and it fucking sucks.” Getting that is a function in just being there.

TM: When you decide you wanted to make this film, how loud was the voice in your head that said, “I really, really hope this does end up being a close race?”

DM: Plan A was that he was likely to lose, and I knew that we could make a strong film even in the case of a loss. I took a lot of inspiration from the movie Street Fight, which is about Cory Booker’s first mayoral campaign in Newark, which he loses. That film went on to be nominated for an Academy Award. But I did feel like if Beto lost by 15 points or more, it would be harder to make a great film.

TM: Ted Cruz doesn’t appear very often. Did you want more access to him? Was there a scenario in which he would have become a bigger part of the film?

DM: Yeah, not really. I felt like we wanted to make a fair film, but not a film that was necessarily balanced in terms of its coverage of the candidates. In other words, we were making a film with a strong point of view, which was through the eyes of this candidate, his family, and his team. And we wanted to see Cruz the way that Beto and his team were seeing Cruz, which was largely through the news, through Twitter, through the negative advertising that was coming at them. This is not a hagiography about Saint Beto who is this perfect candidate. But I didn’t feel like we needed to show Cruz in order to do that.

TM: Did you model this after other campaign documentaries? Running With Beto is really different from a film like The War Room, about Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, which focuses mostly on his top advisors and not Clinton himself. Your film is very focused on Beto and his family, and it’s not as much about the machinations of the senior staff.

DM: Yeah, it wound up being a little bit less about the x’s and o’s of the campaign and more about the lived experience of it for Beto, his family, and then the sort of ground-level supporters that were out there. But it’s funny you mention The War Room. It was actually, in some ways, a different D.A. Pennebaker film that was a big inspiration for me: Don’t Look Back. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it.

TM: That’s the Bob Dylan one right?

DM: Yeah, I highly recommend it. It’s basically about Bob Dylan’s first big tour of the U.K. after he has really hit it big, and it’s just this wonderful cinema verité, scene-to-scene, immersive film that is following kind of a truth-teller who has really taken off and what the experience of that attention, that pressure, that excitement is really like to live through. You see him experiencing fame for the first time.

And so I felt like Running With Beto in many ways was like following a rock band that hit it big but refused to change any of what had gotten them there, you know, kept playing the same hits, kept the same small team together, and were sort of living through this wild explosion of attention in response to them doing something that was kind of profoundly new in many ways.

TM: Once Beto went Bob Dylan on you, did it become tougher to get access?

DM: A couple of months before the election, when Beto had really taken off, and they were just besieged by crews from around the country and from around the world, we were starting to get lumped in with the rest of the media. I was beginning to worry that the behind-the-scenes film we were making was going to wind up looking like something shot from the outside-in. And so I had to reach out to Beto and his wife, Amy, and the senior staff, and say, “Hey, I think we’re making something that could be special, but we really need to preserve some of this access. Here are some key moments that we really are going to need to capture.”

TM: Was there a moment during the year you were filming when you felt like you had it, where you said, “Even if Beto calls me up tomorrow and says, ‘we can’t have you film behind-the-scenes anymore,’ I have all I need for a good film?”

DM: That didn’t come until they invited us into their kitchen on election night after the loss. I wasn’t sure that we were necessarily going to get it, but the fact that they were willing to have us with them in that most vulnerable moment was probably the most special moment of my career.

TM: Did you have any inkling as you were making this film that he was going to end up running for president?

DM: In the closing months of the campaign, you certainly heard chatter about that from political pundits, but I think probably the biggest thing, probably the more relevant answer to that question is we saw up close how challenging it was for his family and his relationship with his family. He was basically home two days a month for two years. It seemed unlikely to me that they would all be willing to go through it again. After the campaign was over, I had thought to myself: “If he doesn’t run for the presidency, this film will help show why he made that decision because of the experience that he and his family had being apart from one another. And if he does run for the presidency, the film will show part of the sacrifice that I think every family involved in politics makes.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- Beto O'Rourke

- Austin