I walked among you, ate your barbecue, listened to your Billy Joe Shaver albums, wept with you when the price of West Texas Intermediate dropped below $27 a barrel. But I was not one of you. Outwardly a normal, functioning Texas human being, I carried within a shameful, gasp-worthy secret: it was 2016 and I had never seen a single episode of Friday Night Lights. Was this series about high school football indeed the most authentic depiction of modern Texas ever to appear on a screen, large or small? I didn’t know. I had to take your word for it.

No excuses; life had just gotten away from me. I had missed out on the five seasons of FNL, and now—five years after the series ended, ten years after it began—the idea of watching it from the beginning when there was already a cresting flood of high- (and low-) quality TV to catch up on felt like swimming against the tide of time. I wasn’t completely out of touch. I had read the H. G. Bissinger nonfiction book that inspired the series and seen the movie that had been released in 2004. I had even played high school football and had known the rapture of hearing hundreds of people chanting my name from the stands (though it turned out I was sitting on the bench and the guy who made the touchdown just happened to be wearing my number that night). But reading the book and seeing the movie and vicariously living the dream weren’t the same as actually watching the series, which was, I was emphatically told by my children and friends, a time-release, long-acting dose of pure Texas culture. And with a ten-year cast reunion scheduled for the ATX Television Festival, in June, I could no longer avoid the sense that a binge-watch of FNL had risen to the level of a moral imperative.

There are 76 episodes of Friday Night Lights, which meant a total eyeball commitment (without commercials, via Netflix) of roughly 55 hours. In my case, the viewing time was spaced over a month and a half, but all those back-to-back episodes still crowded my consciousness and infiltrated my dreams, especially during one weeklong stretch when I had the flu and my mind was burning so bright with fever that the phrase “Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Can’t Lose” demanded to be taken up as an urgent philosophical investigation. (Conclusion: you can still lose.) I watched the first episode with a mild sense of vertigo. The camera work was so fluttery and frenetic that the show looked as though it had been filmed by a hummingbird with a tiny GoPro strapped to its head. In subsequent episodes the cinematography settled down a bit, or maybe I did. In any case, it ceased to bother me and instead captivated me. The darting camera turned out to be an ingenious tool for eavesdropping on intimate moments between characters and for spotlighting crucial plays during the football games.

The TV version of Friday Night Lights, as you knew but I didn’t until I began my viewing project, takes place in the fictional town of Dillon, Texas. Bissinger’s book was set in Odessa, and Dillon—patched together mostly from locations in Austin and Pflugerville—mirrors the kind of scruffy, smallish Texas city where special-occasion dinners take place at Applebee’s and a public directive to bow your head in prayer is never out of place. As the show went on, Dillon seemed to enlarge and contract according to the demands of the story. In one episode a character mentions that the town has only two motels, which I thought odd since it also has streets lined with car dealerships and chain restaurants, a topless bar called the Landing Strip, hints now and then of a real skyline, and a pretty hefty McMansion or two. Geographically Dillon is a little blurry as well, apparently far from an interstate, more East Texas–seeming than West in terms of its African American population, its identity forged by football but its economy based on nothing in particular.

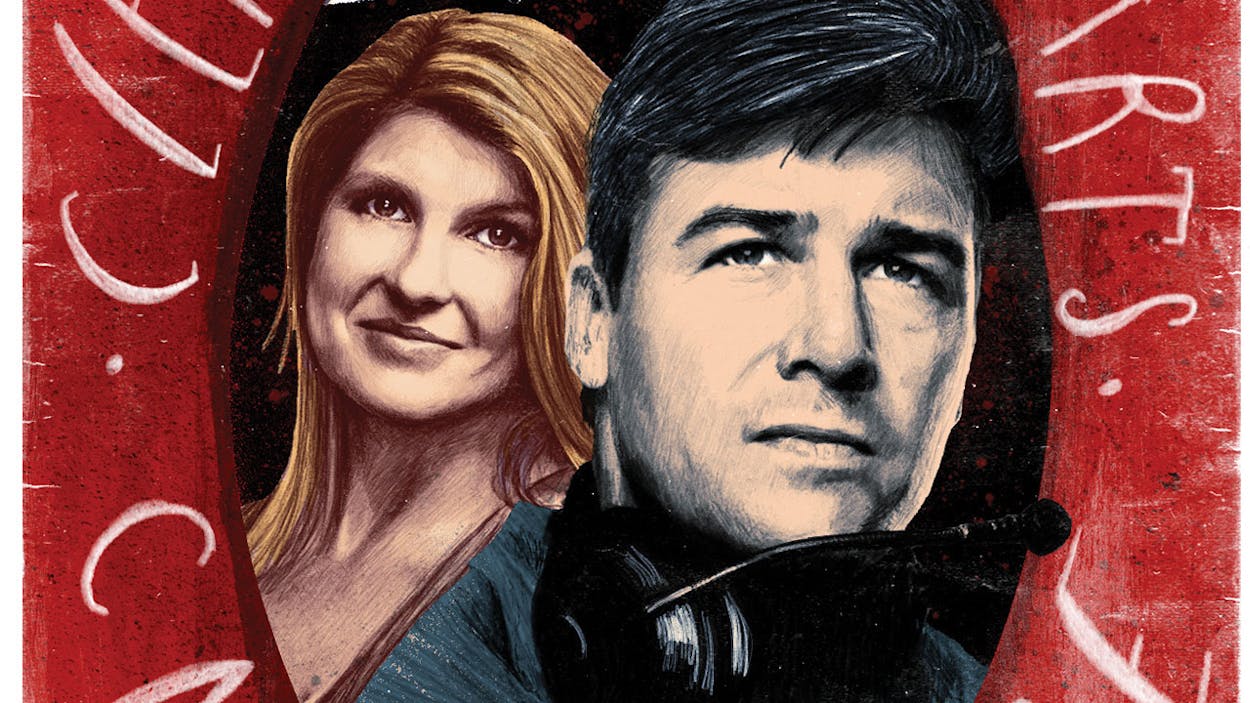

But the people of Dillon instantly snap into place. It misses the point to say that Eric Taylor—the head coach of the state champion Dillon Panthers and, later in the series, of the East Dillon Lions—is played by Kyle Chandler. He’s not played by anybody, he’s just Coach Taylor, the idealized but never sentimentalized manifestation of high school football coachness.

And then there is Mrs. Coach, who goes by the perfectly spelled first name of Tami. After I had emerged from my Friday Night Lights isolation tank and happened to come across an interview with Connie Britton on YouTube, the experience of hearing this Boston-born actor speak without a Texas accent almost skittered me into another dimension. It seemed deeply unnatural that she might say something like “Hi, everybody” instead of “Hey, all y’all”—that Tami Taylor and all her oozy West Texas maternal solicitude was not an inevitable presence but just a character that could be moved on from. Coach Taylor and his wife—who, depending on the episode, is either a high school guidance counselor or a principal or a guidance counselor again—are one of the great soul-mate acts in television history. But their careers are constantly colliding. The coach is a figure of crabby rectitude and rock-solid heartland values that are about five years behind the advancing wave of blue-state culture. He is rarely not in need of a lesson in gender equity from Tami, whose dawning career ambition is an important part of the narrative pulse of the whole series.

Another driving theme is Texas itself. “Here’s to God and football,” the hard-luck heartthrob Tim Riggins drunkenly declares to his best friend and teammate Jason Street in the first episode. “Good friends livin’ large in Texas. Texas forever, Street!”

Texas forever: it sounds hokey and is meant to sound hokey, to depict the self-conscious mythmaking of young people at the apex of high school football renown who are beginning to realize there might be shrinking horizons ahead. A few episodes later, “Voodoo” Tatum, a Katrina refugee whom Coach Taylor is trying to recruit for the Dillon Panthers, issues his own counter-manifesto: “This ain’t my home. It never will be. I don’t like the food here, the music, the weather. I can definitely do without everybody going on about the great state of Texas.”

The tension between the conviction that Texas is a land of dreams and the suspicion that it might not be that special after all is one of the elements that keeps Friday Night Lights intellectually honest. But the authenticity is also sustained by a never-ending supply of specific details—the local Dairy Queen knockoff called the Alamo Freeze, the uncommented-upon churchgoing, the precision of the plays that the Dillon coach drills into the heads of his team: “You let the tight end clear. The slot receiver crosses underneath. You hold. You hit the third receiver, who’s running a delay. Can you see that?”

And long before Game of Thrones arrived on HBO, there is Westeros-level intrigue brewing in Dillon. The gallery of people constantly scheming to undermine Coach Taylor includes inflexible bureaucrats, jealous rivals, predatory college football scouts, and pushy fathers who’ll do anything to make sure their sons are in the starting lineup for the big game. On the other hand, throughout all five seasons, the coach has on his side the splendidly realized Buddy Garrity (Brad Leland), the former Dillon quarterback still drunk on teenage fumes of glory, a local car dealer and booster of all boosters who can’t stop screwing up his life but, when it comes to Panther pride, has the pure-hearted devotion of an Arthurian knight.

There were other characters I found just as indelible, starting with Landry Clarke, the nerdish outlier played by Jesse Plemons. Landry is a brilliant creation, though I’m not sure that after they created him the writers knew exactly what to do with him, since his story arc eventually flattens out and he unceremoniously slips off to attend Rice at the beginning of the fifth season. But whenever he’s on-screen he’s a heartening presence, the boy who is not going to peak in high school, who remains stubbornly unnoticed and unappreciated by almost everyone, including Coach Taylor, who keeps calling him Lance instead of Landry. And there’s Landry’s best friend, quarterback Matt Saracen (Zach Gilford), abandoned by his mother and more or less abandoned by a father for whom fighting in Iraq is less intimidating than making small talk with his son. Matt’s devotion to his dementia-afflicted grandmother was the plot element that kept drawing me back the most reliably, even during the silly season of Friday Night Lights’ second year, when the world’s most beautiful Guatemalan caregiver inexplicably showed up at the Saracens’ door to look after Grandma and fall in love with Matt.

Oh, that season two! The season of a thoroughly ridiculous murder involving Landry and the slinky Tyra Collette, his never-quite-to-be girlfriend; the season of paralyzed quarterback Jason Street going to Mexico for stem-cell surgery and jumping out of a boat in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico; the season of Buddy’s daughter Lyla falling hard for Jesus in a subplot so tepid I could almost hear the yawning and groaning from the writers’ room; the season of Coach Taylor jumping up from his chair in a nice restaurant to wrestle Tami’s blowhard old boyfriend to the floor.

The show got its mojo back, but let’s be honest: Friday Night Lights is great, but it was never flawless. When you watch a series night after night instead of week after week, you gain a God’s-eye perspective you were never meant to have. You see right through it. You begin to realize that things are happening just for the sake of happening, that it’s time for Tim Riggins and his brother, Billy, to make another stupid decision, for Landry not to win the heart of another unobtainable girl, for the new quarterback played by a young Michael B. Jordan to have another run-in with his ex-con father or be lured back into street crime by his surly gangsta friends. The carousel of misunderstanding revolves and revolves. The pot is constantly being stirred without the plot ever quite advancing. What happened to the inappropriate English teacher in season two who looked as though he was going to be such a sexy nemesis to the Taylors’ older daughter? Or the prescription drug addiction that Luke Cafferty (another quarterback: FNL is big on quarterbacks) seemed to be developing? Or the dreamboat hippie football player who came aboard in season five as a presumptive major character but just sort of disappeared? And what’s the deal with that goofy assistant coach who in the end turned out to be just a bundle of random quirks?

I watched too much FNL too fast and have not yet been absorbed back into reality. Until I am, it’s hard to know if these are just quibbles or substantive quarrels. Either way, I can say with clear eyes and a full heart that Friday Night Lights never lost me. And I’m not just saying that because I have to find a way to end this column. In the words of Buddy Garrity, “You can’t fake boosterism. It comes from the heart.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Television

- Friday Night Lights