Behind any chart-topping boy band—whether it’s New Kids on the Block, One Direction, or recent K-pop powerhouse BTS—lies a devoted fan base vital to its success. Texan author Maria Sherman, who was born in Fort Worth and raised in San Antonio, is a “superfan” of boy bands herself. After years of covering pop culture for the likes of Billboard and Rolling Stone, the music journalist and senior writer for Jezebel, now based in New York City, set out to write a book taking a serious look at boy bands through several lenses, including race, gender, and sexuality. The definitive guide is the first of its kind, celebrating not only the bands but also the hordes of fans who’ve been by their sides through it all. “A boy band is a juggernaut pop culture application whose impact is monolithic,” Sherman writes. “Historically, yes, boy bands are hotties who harmonize, but fandom is the only true universal.”

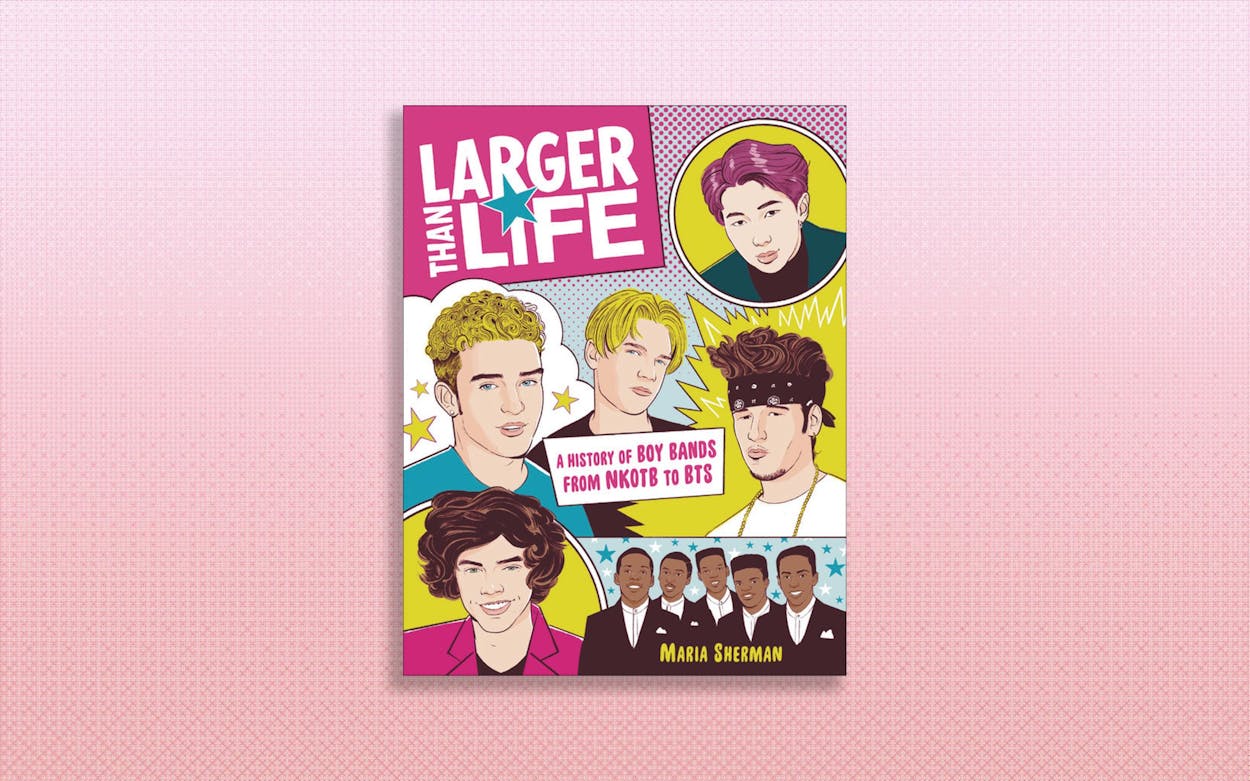

Out today from Black Dog & Leventhal, a Hachette imprint, Larger Than Life offers a comprehensive history of the boy band phenomenon over the years, going as far back as the thirties, when barbershop quartets emerged singing a cappella harmonies, and analyzes what the future of boy bands could look like (think bands venturing out of the pop genre, like King Calaway, or fully LGBTQIA+ crews, like No Daughter of Mine). The book also probes the exploitative business practices that some successful boy bands, such as ’NSync and Backstreet Boys, have been subjected to. Ultimately, it investigates the cultural impact these bands have made, despite being seen as frivolous or trivial by some.

Ahead of the book’s release, Texas Monthly spoke with Sherman about how boy bands are changing, what she hopes readers take away from the book, and Texas’s own boy band, Brockhampton.

Texas Monthly: What was your favorite part about writing Larger Than Life?

Maria Sherman: Probably knowing that by writing it, I was going to legitimize boy bands in some sort of fashion. I always had the idea back in my head that it’s very strange that this book doesn’t exist and I hope a lot of people, especially young women who largely make up boy band fandom, see themselves reflected in it. It’s also just fun to watch a thousand boy band documentaries on YouTube. The whole thing was enjoyable. I just wish I had, like, six years to write it and it became an encyclopedia series, versus a little less than two years and just one book.

TM: Have you considered writing a follow-up book?

MS: I would love to. People have been asking me if I would want to write a book on girl groups and I think that would be pretty interesting. It would open up a lot of the conversation about how pop stars are sexualized, especially at a young age. And so much of the boy band identity is operating in a space where it’s crushable, but not sexual—it’s just butterflies in your stomach and no touching and the hand-holding stage forever. I think if I were to write about girl groups that would be explored in a more explicit way of how those people are sexualized.

I also think it would just be fun to explore boy bands as a topic in a racial history or queer history. I allude to that in the book and I wish I had more space for that. But I really hope this is a primer for people so they can make connections in the story that maybe they otherwise wouldn’t. I also hope other people write boy band books, because it would be really thrilling. Someone’s got to write the definitive One Direction book I’ve been waiting for.

TM: Did anything surprise you while you were researching and writing the book?

MS: Definitely how connected everything seems to be. I knew that there were layers that existed throughout the boy band history. This is before my time, but I was aware that Maurice Starr developed New Edition and New Kids on the Block. I didn’t realize how quickly that jump was, even the fact that [NKOTB] were supposed to be the white New Edition feels like a very obvious through-line. Or the fact that the Backstreet Boys sort of happened because Lou Pearlman wanted to do what New Kids on the Block did. And then in the U.K., with Simon Cowell appearing much more frequently than I thought. As an American, I had no idea. I just thought he was the American Idol guy and then the One Direction man.

And then also so much of the boy band story is about these exploitative practices behind the scenes. It’s a lot of business exploitation and unsavory topics people don’t like to talk about, like sex crimes and then, later in the hip-hop chapter, stuff about drug use. And I was always conscious of Lou Pearlman as this sort of horrible player, [and] the unspoken abuses that continue to be hidden in the way that pop music tries to hide negativity because it’s bad business. But unpacking that and laying it all out there felt like the pieces were coming together. I felt like the meme of that woman with all the math on her face.

TM: As a fan, how do you reckon with knowing about those exploitative practices but also enjoy this music?

MS: It is challenging. And one thing that I find really interesting about it is that it was so hidden and the internet has a tendency to expose ills in a way that maybe otherwise we wouldn’t have access to, or there would be no transparency. Up until now—with K-pop fandom being a digital-native audience—I don’t think boy band fans have ever really had to interrogate what their fandom means, because they had no idea that these things were happening behind the scenes. Or if they did, they probably just thought it was bad business practices, such as bands protesting Pearlman outside of the courtroom with ’NSync.

It is just crazy cognitive dissonance and it’s challenging to unpack. And I think it’s up to the individual to reckon with that. At the heart of it, though, I try to make the argument that if you enjoy this music and it means something to you and it gives you something—and if that’s something that’s feeling good or a distraction or whatever—there’s an inherent value in that. But that doesn’t mean that we as women fans should have the privilege to ignore some of the seedier aspects of it. And nothing is as pure as it seems.

TM: Do you feel like we’re steering away from those practices since these things are coming to light more with the internet and increased access to this information?

MS: Yeah. I really think that because fans … who are going to spend the money and support things that reflect their value systems are being more critical and less complicit when they recognize something. And I’ve noticed that even with K-pop fandom, because they take a participatory role in their consumerism. If they see something that’s unjust, they’re very vocal about it. And we’ve seen that reflected recently with BTS posting about Black Lives Matter and donating a million dollars to the movement and even shutting down the Dallas iWatch app on May 31 by flooding it with fan cams. I was really proud of that: that’s doing something good for my state and for those protesters. It’s clear that boy band fans specifically, but also young pop fans at large, are interested in figuring out what’s going on and being very critical of it with the hope and the ambition of it changing.

TM: What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

MS: I hope that they interrogate the idea of boy bands being “uncool”—why do we believe that? Because there are so many unconscious biases that everybody has that can come down to what is considered legitimate or valued. I hope they see this and think, “Oh, maybe people are dismissing me because of this greater patriarchy”—for lack of a more nuanced term.

Also, it was really crucial to establish this framework as existing in Black and brown communities first and foremost, and then be taken away from them. It’s interesting to me that in the section where I talk about the etymology of boy bands, we weren’t using the term “boy band” until New Kids on the Block happened. We’re not even defining the history until it’s already divorced from the Black source material. It makes me so mad. If you don’t go back and write that history, is it ignored or is it just rewritten as something else? I think that’s what happened with New Edition. We just think of them as an R&B group, but they were children singing and dancing together—there’s nothing more boy band than that.

Also, hopefully [readers] get a tinge of optimism at the end, because it is interesting to see how artists are acknowledging the boy band formula and continuing to dismantle it. The best example of that is Brockhampton.

TM: Do you feel like Brockhampton is redefining what a boy band is?

MS: There are contemporary boy bands that are huge—the obvious example being BTS. [Brockhampton] is sort of an alternative that I think still deserves space. It’s interesting that they came together in the way that they did, which was a post in an online Kanye fan forum. There’s something really DIY about that, which inherently is the antithesis of a boy band.

I was thinking about the role that Texas has played in the boy band story beyond the Dallas iWatch stuff. In the Jonas Brothers documentary Chasing Happiness, they talk about how they didn’t realize that they were famous until they played at the State Fair in Dallas in 2007 and 50,000 kids showed up. Someone told them that the line was going all the way up to Oklahoma. That’s a great hyperbole, but I think there always has been such a large boy band community in Texas. And it makes so much sense to me that Brockhampton—a hip-hop collective that’s labeling itself as a boy band—would come from the state where this is already such a popular thing.

TM: Would you say that Brockhampton is paving the way for other Texas boy bands?

MS: I hope so. I search for boy band names on Twitter, just because I’m curious about whatever conversations are happening, and it does seem like there is a pride in Texas, with Texas fans [claiming] ownership over Brockhampton. Even though they’ve been in L.A. for a considerable amount of time, their Texas identity obviously plays a role, like with them yelling “yeehaw” at concerts. I imagine there are budding boy bands trying to develop themselves in Texas. It’ll be cool if there’s a coed post-Brockhampton group in the works. If that doesn’t exist, I really hope somebody reads this and decides to get together and make that happen.

TM: Are there any other Texas boy bands that you’ve seen that you think are on the come up?

MS: No, and it breaks my heart. But I’m sure it’s just a matter of time. There really aren’t Western boy bands that are ever going to successfully compete with K-pop. But Brockhampton really is the sort of exception because they’re occupying a space that no one even knew was vacant. They created it themselves, which is exciting. So I’m actually going to change my answer and say the only American boy band worth a damn in this modern age is Brockhampton from Texas. I’m proud.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.