Robert Earl Keen was coming home. The Houston-born songwriter was unwinding in the back of his tour bus as it barreled west through Louisiana in the predawn dark of an early-August morning. He and his band had been traveling at a relentless pace since March, crisscrossing the country to perform at arenas, theaters, festivals, and clubs from Santa Cruz, California, to Portland, Maine. Keen was exhausted but feeling good. They’d played well that night, and now they were entering the tour’s last leg—a final run through their home state. For months, they had been plagued by a string of lousy luck, but as Keen started to drift off to sleep, he thought maybe the curse had finally been lifted. That’s when the bus caught fire.

Just hours before, Keen and his band—Bill Whitbeck, bass; Brian Beken, fiddle and lead guitar; and Tom Van Schaik, drums—had stormed through a two-hour set at the House of Blues in New Orleans. About a thousand diehards had shown up to hear the meticulously crafted narrative songs that have earned Keen acclaim as one of his generation’s finest lyricists. They’d also come to party. For decades, Keen concerts have been notoriously raucous affairs. But the crowd that night wasn’t just rowdy, it was reverent. Like members of a boozed-up church choir, fans swayed to “Gringo Honeymoon” and sang every word to “The Road Goes On Forever” (a Keen-penned tune that is now considered country music canon). Standing in the middle of that tipsy ensemble, I watched a big, bald dude on the front row weep during “Feelin’ Good Again.” He wasn’t the only one whose cheeks glistened before the night was over. For most, this would be the last time they’d ever see Robert Earl Keen take the stage.

Back in January, Keen, who had just turned 66, made a surprise announcement. In a short video released on social media, he sat on a sofa, wearing a floral blazer and a maroon tie, and addressed his fans. His typically unruly gray and white hair was neatly cropped, and his famously husky voice was unusually tender: “It’s with a mysterious concoction of joy and sadness that I want to tell you as of September 4, 2022, I will no longer tour and perform publicly.”

An epic coast-to-coast tour was announced shortly afterward—95 shows in just six months. The schedule was ambitious even for a veteran like Keen, but he’d built a loyal following and felt compelled to visit as many places as he could. This celebratory send-off was for the fans as much as for him. As he’d explained in his video, he wasn’t in bad health or experiencing an existential crisis; he’d made this decision because he wanted to quit the road while he still loved performing, to go out on his own terms while he was still near the peak of his artistic powers.

At first, everything went as he’d envisioned. The year started with a solid string of gigs, including a tribute concert honoring his late mentor, Texas folk singer Nanci Griffith. That was followed by a benefit show with the young Kentucky songwriter Tyler Childers that raised more than $450,000 for the Hill Country Youth Orchestras, a nonprofit based in Kerrville, where Keen has lived for nearly two decades. But right as the tour was set to kick into high gear, in the spring, the bad luck began.

The band was preparing to film Keen’s fifth headlining appearance on Austin City Limits when Keen’s back gave out. He went from one doctor to another looking for a remedy. Instead of relief, the medications he was prescribed caused a series of allergic reactions. His weight plummeted from 210 to 185 pounds in ten days. His feet swelled to the point that he couldn’t wear boots. On the day of the ACL taping, in April, Keen’s bad back forced him to deliver his songs while sitting on a tall stool at center stage. Earlier that day, he’d taken a pill that triggered yet another allergic reaction. Two red welts that looked just like crosses appeared on the inside of his right forearm. “If you don’t think I’m cursed,” Keen would tell people, as he rolled up his sleeve, “check this out.”

Shortly after, Van Schaik broke an elbow. The wounded drummer managed to rearrange his snare setup and play through the pain. But the blows kept coming. That same month, the mother of Keen’s longtime bus driver died unexpectedly. The band canceled a mid-May recording session, and because of other forces beyond his control, Keen had to push the release of his thirteenth studio album, which had been scheduled for the summer, to next spring. Then, in July, the morning that the band was set to start a two-night stand at Irving Plaza, in Manhattan, Keen woke up to find that half his face was paralyzed. He was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, a condition that usually lasts at least two weeks. He’d have to sing out of one corner of his mouth. A few weeks later, Beken, the youngest member of the band, at 36, suffered a herniated disc. “Morale,” Keen said, “was at an all-time career low.”

Before the August concert in New Orleans, Keen visited Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo. “I bought four hundred dollars’ worth of voodoo shit to keep evil spirits away,” he said. “I had put it all around that back room of the bus. I had these candles going and these little bitty skeletons and a skull and some sage and some rosemary water I sprayed all over the place—the whole deal. I felt pretty good, like I had something to fight this curse with.”

But after the show, as the bus neared Gonzales, Louisiana, at around three in the morning, the engine started smoking. The driver quickly pulled onto the shoulder of Interstate 10. The door to Keen’s quarters flew open. “The bus is on fire!” the stage manager, Colton King, hollered. “Get out now!” Leaving his clothes and guitars, Keen rushed out with the rest of the band. He stood and watched as flames licked up the side of the bus, where he’d been half asleep a few moments before.

At that point, some folks might’ve considered throwing in the towel. But Keen had never been the kind to quit when things looked bleak. He’d struggled for much of his career—against being boxed in by critics, against being compared with his more famous peers, against his own rambunctious fan base, and against being defined by his Texas roots, even as he came to embody “Texas music” as much as any artist of the past few decades. He was only half joking when he’d told reporters over the years that his strategy for surviving the music business could be summed up as “brute force and ignorance.” His bullheadedness, coupled with his songwriting prowess, had been key to his ascent from front-porch-picking Aggie to Americana music icon.

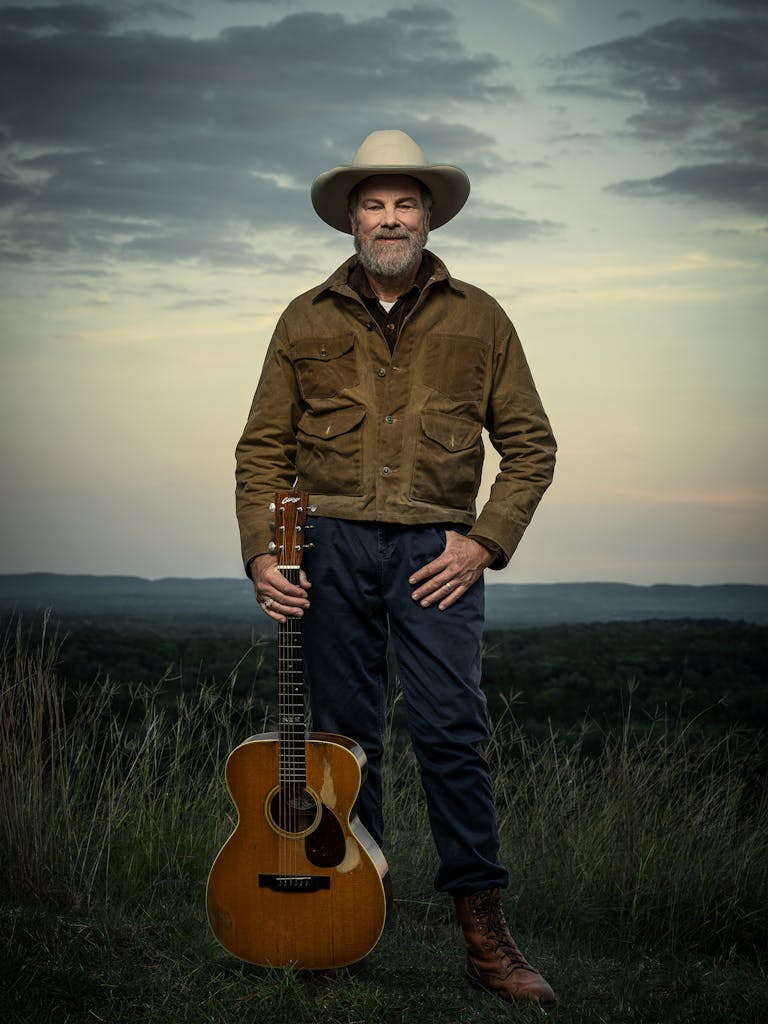

Back in April, Keen drove me from his Kerrville headquarters (a three-bedroom house converted into offices full of merch and memorabilia) to his five-hundred-acre spread some twenty miles to the southwest, near the small town of Medina. Behind the wheel of his black SUV, he steered us through a landscape of knobby limestone hills smattered with scrub oak and cedar brush. He unspooled tales about touring with Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt and about the blissful days of learning to pick guitar with his snuff-dipping, fiddle-playing buddies at Texas A&M. In person, his stories flow much like they do when he’s onstage, which is to say they’re brimming with humor and they often meander, picking up peripheral details and straying into side narratives until he somehow wraps them up with a perfectly executed punch line or a clarifying moment. Among all his artistic gifts, telling stories might be what Keen does best.

Making people laugh isn’t far behind. After we’d arrived at his modest one-story ranch-style house, Keen asked if I’d like a glass of red. It was three in the afternoon on a Tuesday, but I told him sure. He set out two glass goblets, then headed to the fridge. He returned bearing an enormous jug of crimson-colored Hawaiian Punch. He filled our glasses. “If you’re the least bit diabetic, you’re going to go into shock.”

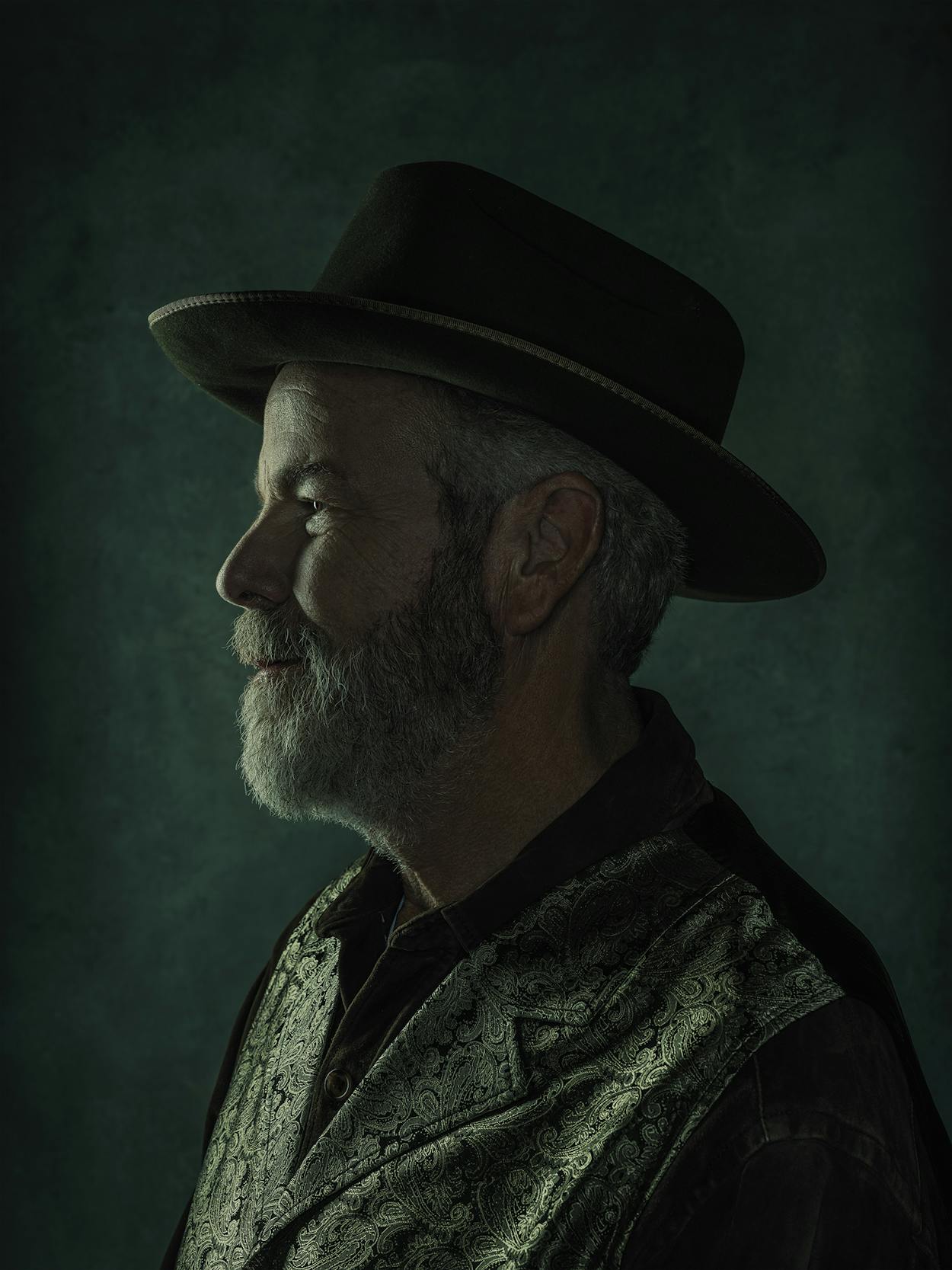

Keen loaded a wad of Copenhagen (for the snuff connoisseurs: original, long cut) into his bottom lip and we set off in his Kawasaki Mule four-wheeler for a tour of the property. In some ways, Keen is exactly the guy you’d expect to have written “The Five Pound Bass” and “That Buckin’ Song.” He loves to hunt and fish and knock back a couple of cold ones. But he doesn’t normally dress like the average country troubadour. On this day, he wore a forest-green short-brimmed Open Road Stetson, a maroon linen sports coat, a vest, a tie, baby-blue chinos, and a pair of white and blue sneakers. The ensemble gave him the vibe of a dapper, slightly eccentric Southern gentleman on his way to Mardi Gras. A pretty standard outfit for Keen.

Up a hill, past a small swimming pool, three horses milled about in their pen, a few goats stood in the shade of a mesquite tree, and a donkey wandered around, looking a little lost. Postcard views of the Hill Country stretched out in every direction. Even with the grass yellowed from drought, the place was beautiful. Keen told me his wife, Kathleen, was the one who’d found it for sale back in 1995, when they were living in Bandera.

“We had a little office, and my wife comes in and says, ‘I’m gonna go look at this ranch.’ I said, ‘We don’t have any money.’ She goes, ‘I don’t care. Doesn’t stop me from going to see a ranch.’ ” Reluctantly, Keen joined her. They both fell in love with the land and made an offer. Keen then had to figure out where he was going to find the cash. Soon after, an unexpected check for $50,000 arrived—royalties from a Jeff Foxworthy record that featured Keen’s song “Copenhagen.” “To this day, I’ve never found anybody who’s ever heard that record, but it’s him singing comedy songs, and he sold them at truck stops,” Keen said. “I didn’t even know he’d cut the f—in’ song! But I tell you what—thank you, Jeff Foxworthy.”

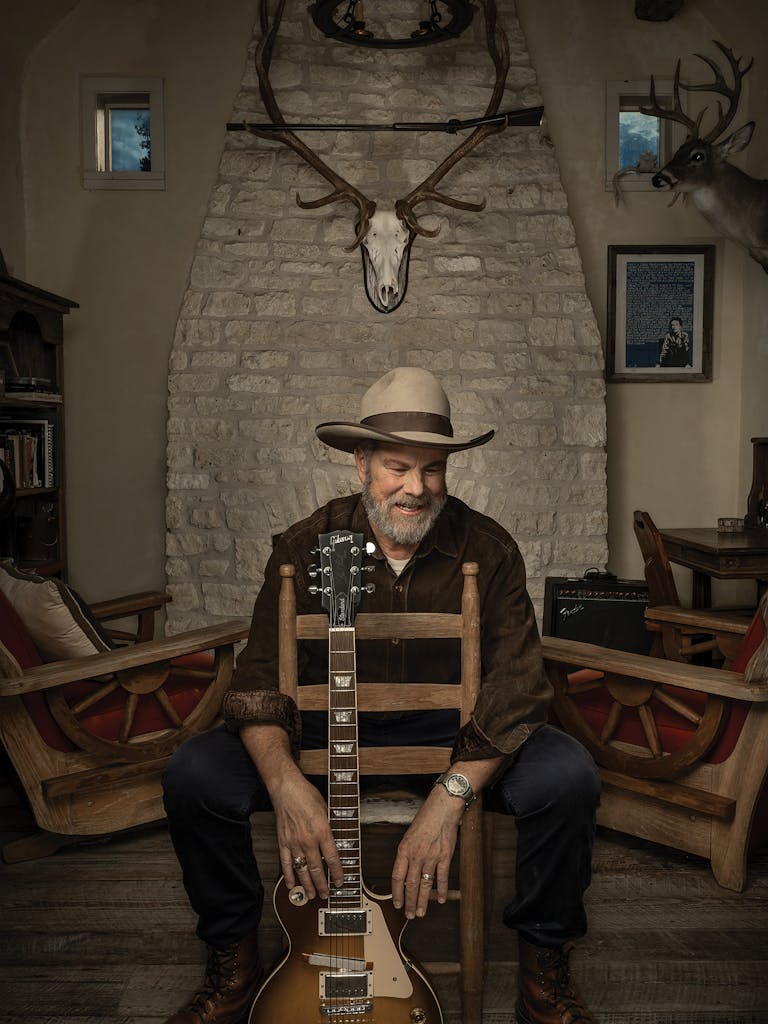

Keen and Kathleen, along with their two daughters, lived on the ranch from 1995 until they moved into Kerrville, in 2005. Keen still spends a good chunk of his time out here, especially when he’s got a creative itch. He pulled up to a corrugated tin warehouse he calls the Snake Barn. The building earned its name because for years it had been filled with junk and, as Kathleen warned, probably rattlesnakes. But they’d cleared out the cavernous room, swept the concrete floor, and converted the space into a kind of all-purpose studio. This was where the band escaped to play music during the long, lonely days early in the pandemic.

They also started shooting music videos. “I like theater,” Keen said, as we looked around inside. “So when we do a video, I like to build the sets to kind of fit the music or whatever we decide the theme is. People keep asking me what I’m going to do. I’m like, ‘Well, I’m not quitting music.’ This is the stuff I’ve been wishing I had more time to do.” And of course, he’ll continue doing what he loves most: writing. For that, he heads to the Scriptorium.

Among Keen devotees, the Scriptorium is a near-mythical place. The one-room stone structure sits atop a plateau, above the ranch house and Snake Barn, overlooking the scrubby countryside below. With its wooden shingles, vaulted A-frame roof, rough-hewn beams, and cream-colored limestone bricks, it could be mistaken for an old church. When Keen comes up here, he often stays for several days, sometimes a week or more, and he lives like a Hill Country monk, phoneless and with just venison sausage, white bread, and mustard for sustenance. The inside is austere. There’s no central heat or AC, though there is a fireplace. The walls are mostly bare: a black and white photo of seventies-era Willie Nelson, a few mounted racks of whitetail and elk, a pastel painting by legendary songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen, and a framed poster for There Will Be Blood, Keen’s favorite movie. Filling out the room are two vinyl chairs, a rolltop desk with sundry talismans (an old tab-topped can of Shiner, a Big Lebowski bowling pin, a Big Chief notepad), a jailhouse-style iron bed, and a bookcase populated by a wide range of texts: John Cheever short stories, West Texas history, Southern Gothic novels by Larry Brown, a dictionary/thesaurus, and several titles by Keen’s favorite author, Cormac McCarthy. Keen sank into one of the red vinyl chairs. He seemed more at ease than I’d seen him all day.

This is where Keen does his best work. “What I want to do,” he said, “is get to a place in my head where I can let all that junk go away. And I might sit here a couple of days and write some really crappy songs. Then I try to get to a place where I’m in touch with my surroundings. This has always been my favorite place to be, as far as writing. In general, I’ve probably written eighty percent of my songs outside, either on some porch or some backyard or whatever. I don’t know why, but I really like being outdoors. And this is as close as you can get to being outdoors and indoors at the same time.”

Keen’s prodigious catalog of songs is one of the most impressive ever created by a Texan. His expansive discography is near-impossible to sum up, but the bulk of Keen’s songs might best be described as four-minute short stories set to melodies that lodge in your head—forever. In fact, it’s easier to convey the literary quality of Keen’s tunes by comparing him to authors rather than songwriters. “Shades of Gray,” for instance, about some juvenile delinquents rustling cattle, sounds like something Denis Johnson might’ve written. The star-crossed lovers of “The Road Goes On Forever,” bound by violence and misfortune, could have wandered off the pages of Elmore Leonard. The stunningly evocative details of small-town Texas found in so much of Keen’s work (see: “The Front Porch Song”) recall Larry McMurtry. And McCarthy creeps up time and again in Keen’s matter-of-fact use of bloodshed and cowboy imagery, best exemplified in “Whenever Kindness Fails.”

“The thing that stands out for me the most is that he tells the truth,” Nanci Griffith, an acclaimed songwriter in her own right, told Rolling Stone in 2018. “His songs sound like they wrote themselves. They don’t sound like somebody sat around and labored over them; they just sound like they were always there.”

Griffith was the first to record one of Keen’s songs—she cut “Sing One for Sister” on her 1987 album Lone Star State of Mind—but many artists have since followed. Some of the most noteworthy covers include Gillian Welch’s gorgeous version of “I’ll Go On Downtown,” Lyle Lovett’s elegiac take on “Rollin’ By,” Shawn Colvin’s stripped-down “Not a Drop of Rain,” and the Chicks’ collaboration with, of all people, Rosie O’Donnell, on the dysfunctional holiday classic “Merry Christmas From the Family.” Keen’s most popular song, “The Road Goes On Forever,” was first covered by Joe Ely, in 1992. Three years later, the greatest country music supergroup ever assembled, the Highwaymen (Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson), would use the song as the title track of its final album.

Then, in 1998, the king of country himself, George Strait, recorded “Maria,” the first of two Keen tracks he took into the studio. As Strait tells it, he was driving home late one night after one of his son Bubba’s junior rodeos when the song came over the radio. “I’d heard it before, but for whatever reason it just hit me like a ton of bricks that night,” he recalled in an email. “My version is a bit different than Keen’s, as you would expect. His is better.” Strait remains a fan. “I, like all other Texans, love Robert Earl’s music. He’s written some classics that will live forever.”

Yet for all of Keen’s critical acclaim and all the admiration he’s received from fellow songwriters, he has never broken through to mainstream stardom. He’s had no number one songs or chart-topping albums. He’s never won a Grammy. For the most part, Keen has kept the music industry at arm’s length, which has, in some ways, hobbled his commercial success. It’s also the very thing that has drawn so many to his music.

When I first heard him, in 2003, I was nursing a recently acquired distaste for country. My West Texas granny had reared me on a healthy dose of the older stuff (Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams), but as an angsty teenager I leaned into punk rock. Then, late one Friday night my freshman year of high school, I came home to my younger brother Brighton playing a song on the family computer. “Mom got drunk and dad got drunk / At our Christmas party,” a voice—half rasp and half warble—sang from the speakers. “We were drinking champagne punch / and homemade eggnog.”

I sat down and listened. Here was a Christmas song not about chestnuts or sleigh bells but about mobile homes and blown fuses and trips to the convenience store for tampons and more tampons. The lyrics were funny, but more importantly, they felt true. “Who the hell is that?” I asked Brighton. He cued up another song. “Robert Earl Keen.”

Music was far from Keen’s birthright. He grew up in Bellaire, a suburb southwest of Houston. His father, Robert Earl Keen Sr., was a petroleum engineer and geologist. A few years after Keen was born, in 1956, his father drilled what was then the world’s most productive oil well, in Webb County. Keen’s mother, Juanita Puckitt Keen, was an attorney at a time when relatively few women were practicing law. Neither parent was musical, but Juanita loved pop-country musicians such as Marty Robbins and had a penchant for poetry. She’d pay her young son a quarter to memorize works by Robert Frost and Countee Cullen. At age eight, Keen wrote his first song, an ode to the enchiladas at Larry’s Original Mexican Restaurant, in Richmond.

Keen’s childhood got a jolt of drama when he was seven and two teenage half brothers from one of his father’s previous relationships showed up from California. “They were totally juvenile delinquents, like, hell-raisers, and I didn’t know them,” Keen said. “My house went from this perfect little family to this insanity kind of thing.” But one of those older brothers, Dan, was also into music, and he exposed Keen and his younger sister, Kathy, to new artists, including a not-yet-bearded Willie Nelson. Keen was soon pedaling his bicycle a mile to the record store.

Later, the family moved a few miles farther west, to Sharpstown, where Keen went to high school. He wasn’t a particularly good student. “I was still really outdoorsy,” Keen said. “I had cousins that had ranches out in West Texas and, man, that was what I looked forward to every time I was off of school. Christmastime, I was out there hunting. In the summer, I was out there working goats and cows.” At home, Keen did his best to lead a rural life despite being trapped in suburbia. He rode horseback on overnight trail rides and closely followed rodeo. He spent weekends traveling to nearby roping and roughstock events and idolized the cowboys. His hero was Phil Lyne, the all-around world champion in 1971 and 1972. Keen even made his own foray into the sport. As he’d later joke on The Live Album: “I had a rodeo career that lasted fifteen seconds—that’s five bulls times three seconds apiece.”

When he wasn’t in the bleachers at some county arena, he and his best friend, Bryan Duckworth, drove around in Duckworth’s rust-red 1970 Ford Maverick, drinking cases of Texas Pride beer and listening to eight-track tapes of bluegrass legend Bill Monroe and Depression-era country singer Jimmie Rodgers. Around this time, Keen’s fifteen-year-old sister Kathy earned a reputation as the “champion foosball player of downtown Houston,” and he often acted as her chaperone when she went to play in bars. While Kathy smoked Benson & Hedges cigarettes and dominated the foosball tables, Keen would wander off and listen to whoever was strumming a guitar in the back room or on a small corner stage. Keen skipped his senior prom in 1974 to watch Willie Nelson play a Pasadena honky-tonk called the Half Dollar. That same year, Keen also attended Nelson’s second Fourth of July Picnic, held in College Station. He had to hitchhike home to Houston after his Chevrolet Bel Air caught fire and burned to a blackened husk in the parking lot.

Still, Keen wasn’t musically ambitious. He’d never even picked up an instrument. That changed shortly after he followed Duckworth to Texas A&M. Keen’s first semester as an Aggie was rough. “I got my first D in biology,” he said, “the lowest-level biology class that I could take. I thought, ‘You know, this studying stuff I’m not very good at, so I need to find something else.’ ” What he found during a trip home was his sister’s nylon-stringed Alvarez guitar, unused and stashed away in her closet. He took it back to College Station, and for the first time he knew what he wanted to do with his life. “From about the time that I could really strum a D chord, I never had much serious thought about doing anything else.”

During the summer break, Keen roughnecked on oil rigs in East Texas. He brought a guitar and a songbook titled something like “Ten Most Famous Country Songs.” The first tune he committed to memory was Nelson’s “Hello Walls.” Upon returning to A&M, Keen moved into the now famous house at 302 Church Street. Every Keen fan knows this part of the story by heart, and many can recite verbatim the version Keen tells on The Live Album. For everyone else: the Church Street house became an informal salon for any Aggies who wanted to drop by and pick tunes and drink beer. Impromptu sessions of bluegrass and traditional country could be heard at all hours. One day a curly-headed journalism major pulled up on his ten-speed. His name was Lyle Lovett.

Keen and Lovett’s lifelong friendship began on that porch. It was Lovett who suggested that Church Street’s ragtag ensemble of musicians, including Keen on guitar and Duckworth on mandolin, call themselves the Front Porch Boys. Soon the group was booking gigs: Methodist spaghetti suppers and the rodeo in downtown Bryan, which they played while crammed into the bed of a pickup. Keen switched his major from agriculture to English, and though he enjoyed the subject, he was suspended for poor grades. He spent the time away from school tripping pipe on oil rigs, including the summer he spent living with his brother on the Texas coast, partying when he wasn’t in the derrick. (He’d later memorialize their misadventures in “Corpus Christi Bay.”) Keen eventually earned his degree, in 1980, and in November of that year he moved to Austin to work as an oil proration analyst at the Texas Railroad Commission.

“It was totally a bureaucratic job, like a pencil-pusher thing,” Keen said. “It wasn’t hard. You didn’t have any homework after you finished your day, so it allowed me to go around and play every place I could.” That is, if he could persuade someone to book him. “There was a place called Xalapeño Charlie’s down on Barton Springs. It was really funky. Charlie had this old tin shack in the back where he kept extra stuff, and I asked him if I could go play back there and set up a tip jar. Another place was Spanky’s Hot Dogs. I talked that guy into letting me just kind of stand out on the sidewalk and play. And then there were a lot of places that were, you know, real venues that had music, and I would be hauling my ass over there at five o’clock and banging on their door.”

At the time, the Austin scene was more interested in the electric blues of Stevie Ray Vaughan than in the folk-country sound Keen had been cultivating at A&M. But Keen was stubborn. He hounded the owners of Emmajoe’s for more than a year before they finally agreed to let him open for bluegrass musician Peter Rowan. The club turned out to be a receptive environment for the new material Keen was writing, and it soon became one of his regular gigs. He got his first small taste of success when he won the vaunted New Folk Songwriting Competition at the 1983 Kerrville Folk Festival.

Around this time, his buddy Lovett handed him a book: How to Make a Record. Keen read it from cover to cover and basically did what it said. He hit up twenty friends for $100 each, borrowed $2,000 more from an Aggie banker, and recorded his 1984 debut, No Kinda Dancer. It opens with this verse:

The first of the month

Brings back the notion

Of a big round white dance hall

And a cool summer night

Red cherry faces set black shoes

in motion

To the oom-pa-pa rhythm of a

German delight.

That same year, Tracie Ferguson, who booked bands at Gruene Hall, in New Braunfels, went to watch one of Keen’s sets at Emmajoe’s. She brought along her friend Kathleen Gray.

“We went down there and got really, really drunk,” Kathleen told me. “And I think we were the only two people in the audience. Robert did this great song called ‘Yankee Ingenuity.’ The last line of it was ‘Do they make a Shiner Light?’ At that time it was hilarious. Now they make a Shiner Light.” She was five years Keen’s junior, but they became friendly. She was an intern at the PBS show Austin City Limits, and the two connected over music. Both were in relationships, but they ran into each other at Nanci Griffith’s ACL taping and met up at the Texas Chili Parlor afterward. “We just hung out until they kicked us out,” Keen said. They’ve been hanging out ever since.

With Kathleen on his arm and a record under his belt, Keen considered his next step. He was barely making any money and by then had blown through a series of crappy day jobs, including construction and a four-month stint at the IRS. Then he ran into a pal, San Antonio–raised songwriter Steve Earle. “Steve told me there were too many pretty girls in Austin, too much cheap dope, and that it was too close to Mexico,” Keen said. “It was too easy. So I had to move to Nashville. I had to suffer for my art. And, man, did I suffer.”

Though he wrote about snuff and dance halls, Keen was more mild-mannered folkie than bad-boy country singer, an image popularized in Nashville at that time by Earle and Houstonian Rodney Crowell. Keen wore his long brown hair in a ponytail and had yet to drop the “Jr.” from his name. By coincidence, he’d moved to Nashville the same week as Lovett and Griffith, and while those two were getting attention from Music City execs, Keen was shut out. “I really didn’t have any good fortune whatsoever,” he said. “I had lots of doors slammed in my face.”

For one thing, Keen’s clever songs and nasal baritone came across best in a live setting. But Nashville didn’t foster a live scene the way Austin did. “There was no place to play. There was a time I had to go audition for an open-mic night. I was auditioning a month ahead so I could go play three songs for free at the Bluebird.”

A few months after Keen moved to Nashville, Kathleen followed. The couple planned to get married, though her parents were opposed. “They weren’t going to be supportive of me marrying a man who only had a 1963 Dodge Dart and a Martin guitar,” she said. “As soon as I got in the car and left, they cut me off.” She landed a job at Hatch Show Print, the storied letterpress company known for its concert posters, while Keen worked at Taco Bell, dug ditches, and delivered “I Love You” balloons. They were miserably broke. Still, Keen was determined. He signed a contract with a publishing company and contorted his writing to better fit into the Nashville box. He took whatever gigs he could find, including a monthly show four and a half hours away.

One freezing day in January 1987, he and Kathleen were on the way back from a not-great gig in Kansas. Their car broke down. As Keen tinkered under the hood, a big, gleaming tour bus whizzed by. “Steve Earle” was printed on the side. It took all of Keen’s gig money to fix the car, and when they finally made it back to Nashville, they found that their home had been robbed. The thieves had taken “everything that was important to us, which was a jar of change and an eight-inch black and white television,” Kathleen recalled. The next day it was 2 degrees. Keen shivered over to meet Kathleen at a Chinese cafe near her workplace downtown. As he’d later sing in “Then Came Lo Mein,” he finally snapped: “I was steamed, I was fried / But you stood by my side / When I had my nervous breakdown.”

“That was on Friday,” Kathleen said, “and by Monday, I’d called my parents, and they’d offered me a job in Bandera.” After 22 brutal months, Keen’s Nashville dream was over. He returned to Texas tuck-tailed and sure that his career was kaput. “I was completely broken down,” he said. “I had nothing going when we moved to Bandera, and I really did sit around for about five months with my head in my hands.”

While working on his father-in-law’s property in Bandera, a small town about forty miles northwest of San Antonio, Keen met an undocumented

migrant worker. The encounter inspired “Mariano,” a song about a gardener from Guanajuato who “works just like a piston in an engine.”

“That was the turnaround,” Keen said. “I was able to disconnect myself from the thought that I had to write hit songs. After I wrote ‘Mariano,’ I thought, ‘No, this is what I write. This is the kind of stuff I love.’ ”

Keen landed a twice-weekly gig at Gruene Hall, playing for four-hour stretches in the biergarten. These shows pushed him to expand his solo acoustic act. His old pal Duckworth joined him, on fiddle, and was followed by a stand-up bass player and a drummer. Keen’s music started to evolve too—the soft folk tones gave way to a louder roadhouse sound. He signed with North Carolina–based Sugar Hill Records, a label that boasted a roster of serious songwriters, including Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. In 1988 Sugar Hill released Keen’s second LP, The Live Album. As with the first album, the record generated some regional fanfare but didn’t exactly fly off the shelves.

At the time, Kathleen was running a nursing home her parents owned in Bandera. She had a receptionist who, along with her beau, always seemed to find trouble. The woman’s name was Sherry.

Sherry was a waitress at the only

joint in town.

She had a reputation as a girl who’d

been around.

Down Main Street after midnight,

brand-new pack of cigs.

A fresh one hangin’ from her lips, a

beer between her legs.

She’d ride down to the river and meet

with all her friends.

The road goes on forever and the

party never ends.

So begins “The Road Goes On Forever,” Keen’s eight-verse magnum opus, a modern-day Bonnie and Clyde anthem that is now generally considered the best Texas country song ever written. When Keen first recorded the tune on his third album, 1989’s West Textures, he didn’t even consider it the best on that record. He certainly didn’t expect it to change his life.

Steve Coffman, a disc jockey at San Antonio’s KRIO, first heard “The Road Goes On Forever” during Keen’s afternoon sets at Gruene Hall. He started playing it on his weekday morning show, one of the few programs that allowed their deejays the creative liberty to stray from the three-minute cookie-cutter country tracks that ruled the airwaves. The song was an instant hit with Coffman’s listeners. Joe Ely cut a version, then so did the Highwaymen. Keen’s cult following had begun.

By the mid-nineties, Keen had released three more albums that would become classics: A Bigger Piece of Sky (1993), Gringo Honeymoon (1994), and No. 2 Live Dinner (1996). These were kerosene on an inferno. Keen’s audiences grew larger and larger; they also became wilder and younger. Bars started selling out of beer during his shows: the Shiner-swilling frat crowd had discovered its new hero. These collegiate kickers and wannabe kickers worshipped Keen, much as young cosmic cowboys had deified Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker in the seventies.

Bill Whitbeck joined the band in 1995, just as the Keen craze was nearing a crescendo. Whitbeck beat out more than a dozen bass players for a spot in the lineup, in part because after his audition he handed Keen a book of Raymond Carver short stories. “I had run into Duckworth about a year before, right about the time Robert blew up,” Whitbeck recalled. “And Duckworth said, ‘Hey, you should come out on Sunday afternoons. We play at Gruene, and people sit on blankets and Robert tells stories.’ So I had this folky sort of idea of what went on. I get the job, and the first gig we played was in College Station. When we walked in, there were eight hundred screaming eighteen-year-olds. I was like, ‘Oh, shit! This is not at all what I thought was happening.’ ”

On one hand, Keen, who turned 39 that year, was grateful for the bibulous youth screaming the words to every song. On the other, there were times when his fan base proved problematic. Keen’s publicist told him that a magazine had refused to review one of his albums because “he’s too much of a frat-party band.” The tension between Keen’s artistic aspirations and his disorderly fans escalated. Two decades after his Chevrolet Bel Air burned up at Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic, Keen was invited to play the festival, held this time in Luckenbach. His short, twenty-minute set happened to fall right before that of folk-country icon Emmylou Harris. When Harris took the stage after Keen, the unruly crowd continued chanting for more REK. Harris was drowned out and quit her set early. Keen was humiliated.

Whitbeck told me that the reputation of the frat crowd distracted from the true essence of Keen’s appeal. “I remember telling somebody that this may be the first actual literature these people have been exposed to,” Whitbeck said. “It wasn’t just stupid songs to elicit a response from a bunch of eighteen-year-old guys; it was real, serious songwriting that they took to heart.” And some fans took it a step further: they picked up guitars and started writing songs of their own. Today, Keen is credited with having inspired an entire generation: Pat Green, Jack Ingram, Reckless Kelly, Cody Canada, Jason Boland, and Randy Rogers, to name a few. By the late nineties, Keen’s disciples had started touring and releasing records—and some, such as Green, did so to enormous success. Radio stations across the state recalibrated their formats to capitalize on the popularity of this subgenre, which came to be known as Red Dirt or Texas country.

“Before Robert influenced all these younger guys, there wasn’t much of a Texas country scene at all,” Whitbeck said. “I mean, people didn’t even think of it like that. Sure, you had the first wave of redneck rock—Jerry Jeff and Michael Murphey and all those guys from the seventies—but looking back, there wasn’t this big scene until all those young guys started wanting to sing because they heard Robert.”

“He’s like the black knight in the Monty Python Holy Grail movie,” Whitbeck told me later. “It’s like, ‘I can’t stand up, I’m still going to play.’ ”

One of Todd Snider’s most popular songs, “Beer Run,” is about a couple of frat guys from Abilene going to an REK show. Charlie Robison reportedly has lyrics from Keen’s song “For Love” tattooed on his chest—backward, so he can read it in the mirror. The Keen phenomenon has even been studied by academics. Pioneering Texas-country deejay Richard Kelly wrote his 2017 master’s thesis about Keen’s pivotal role in the formation of this movement. “As a result of Keen’s inspiration,” Kelly wrote, “these fans launched their own musical careers and created one of the largest and most commercially successful regional music scenes in Texas history.”

Keen was a reluctant figurehead. He chafed at being lumped in with some of these young artists, whose writing he considered subpar. In 2001 a Houston Press reporter asked how Keen felt about having inspired, among others, the then-red-hot career of Green, to which Keen answered, “Do you think ‘inspired’ is the right word? ‘Spawned’ is more the right word—the devil’s spawn.” Keen also felt that “Texas country” was reductive. “I figured out a long time ago that the ‘Texas’ label is not necessarily the right one to be under all the time. I tried to get away from that as much as possible,” he said. “I had always toured outside of Texas—from the very beginning—because I had this whole thing about ‘You can’t be a hero in your own backyard.’ ”

Keen felt more comfortable calling his music Americana, a lyrics-focused roots style that pulls from blues, folk, and rock but has a country backbone. It was first described as a genre in 1995 by the Gavin Report. The radio trade publication was attempting to better define the not-quite-country music being made by industry outsiders such as Keen and Lucinda Williams. As one of Americana’s earliest champions, Keen appeared on the cover of the issue that announced the launch of the genre’s radio chart. Today it’s recognized with its own Grammy category.

In July, I flew to New York for Keen’s back-to-back shows at Irving Plaza. Having seen him play dozens of times, mostly in rural venues across the Hill Country and West Texas, I found it a little surreal to walk past the Flatiron Building and into an REK show.

There were, of course, a fair share of homesick Texpats sprinkled throughout the cavernous, ballroom-style venue, and I noticed a conspicuous amount of maroon for Manhattan. (If Keen played a secret show in an unmarked cave in the middle of Kazakhstan, at least a handful of Aggies would show up.) But this wasn’t the same audience you’d find at Gruene Hall. There were more fedoras than cowboy hats, and at least two couples sported matching athleisure outfits. I wasn’t sure what to make of this Yankee gathering—until the crowd started chanting “Robert! Earl! Keen! Robert! Earl! Keen!” Okay, I thought, they’re pros.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that morning Keen had woken up to discover that he had Bell’s palsy. He could use only the left side of his mouth to sing, his right eye wouldn’t close, and his right eardrum wasn’t functioning properly, so that even quiet noises sounded huge. But Keen does not miss gigs. “That f—er, if he’s got a gig booked, he’s going to play it,” Whitbeck told me later. “He’s like the Black Knight in the Monty Python Holy Grail movie. It’s like, ‘I can’t stand up, I’m still going to play. My face is f—ed up, I’m still going to play.’ ”

Keen came onstage in an all-white suit, a silverbelly hat, and a pair of round-lens sunglasses. He took his seat on a tall swivel chair, and the band launched into “The Man Behind the Drums.” Though he struggled at times, he delivered a solid performance. The crowd loved it. Two Gen Z women held each other through most of the show, singing nearly every song. When guitarist Beken started picking the opening of “Feelin’ Good Again,” I got goose bumps—down to my knees.

I thought back to high school, when my best friend Sam and I would drive around our hometown drinking Coors and listening to Keen. “Corpus Christi Bay” was the first song I remember hearing about roughnecks and rigs; it became an anthem for us kids living in the Permian Basin oil patch. Keen’s music made us proud to be where we were from, even as he refused to peddle the kind of flag-waving sentimentality that other Texas artists were touting to sell records at the time. While I’ve since outgrown a lot of the music I listened to back then, my appreciation for Keen has only deepened. I suspected many in the crowd felt the same way.

Keen’s “brute force and ignorance” has led him to forge a path entirely his own. Sure, he’s played arenas with George Strait, but he’s also toured with the Dave Matthews Band. Though he’s never strayed too far from his country-folk roots, he’s always been willing to experiment. Some of the production on his 1997 album, Picnic (which features a re-creation of his car ablaze on the cover), wouldn’t sound out of place on an R.E.M. record, and 2015’s Happy Prisoner is a return to his first musical love: bluegrass. Over the past decade, Keen has been inducted into the Texas Heritage Songwriters’ Association and the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame. The university that kicked him out for bad grades has since honored him as a Texas A&M Distinguished Alumni. And he eventually made peace with his role as a standard-bearer for Texas music. He was on hand in 2009 when more than two dozen artists got together to record a live album, Undone: A Musicfest Tribute to Robert Earl Keen.

After a second night in New York, I took a train to Washington, D.C., to watch Keen in an entirely different environment. The Birchmere is a five-hundred-seat old-school listening room. Patrons sit at long communal tables covered in red plastic, drinking pitchers of cheap beer and eating plates of fried catfish ferried by servers who know their way around in the dark. That night, the room was filled with government workers dressed as if they were heading to the beach. The bar quickly sold out of Shiner Bock.

Keen is one of the increasingly rare artists with a truly bipartisan fan base. Over the years, he has played campaign rallies for several Democrats, including for then–presidential candidate Joe Biden. He also played at a George W. Bush inaugural ball in 2005. (Bush’s daughters are major fans.) Another admirer is fellow Aggie and former Republican congressman Will Hurd. Keen cites “Mariano” as an example of how music can resonate with folks regardless of their political affiliation. “People love that song,” he said. “And they love it on both sides. But I left it somewhat open-ended. People are able to come to their own conclusions, which is something that I’ve always strived to let them do.”

Keen’s intimate connection with fans was even more evident at the Birchmere than it had been in New York City. I watched as a quiet, bespectacled man, who looked as if he’d escaped from a desk in the bowels of the Commerce Department, grew more animated as the night went on. By the time Keen played “Amarillo Highway,” the man was dancing in his seat and twirling an invisible lasso over his head. I spoke with people from all walks of life, including a New England defense contractor who’d brought an Oklahoma-based colleague and a Midwestern airline lobbyist who just about lost her mind during “Corpus Christi Bay.”

During “What I Really Mean,” I noticed a dark-haired man with a neatly trimmed beard singing along with his eyes closed, completely absorbed. I tracked him down after the show. Richard Fawal is 55, and he told me his family had emigrated from Palestine to Birmingham, Alabama, before he was born. He’d stumbled onto Keen’s music when he moved to Austin in the late eighties. “I just fell in love with the storytelling aspect,” Fawal said. “It wasn’t like anything else I had ever heard.” Even after he relocated to D.C., in 2002, he continued following Keen’s career. “About a decade ago, I picked up a guitar,” he said. “Now I know a dozen Robert Earl Keen songs that I play for myself and when I hang out with friends.”

I saw Fawal again the next night. This time he’d brought his daughter. She was singing along with her dad.

Outside the Birchmere, I sat with Kathleen on a picnic bench while the band loaded up. She has a roving intellect that bounces seamlessly from Russian history to peanut farming in South Texas. While Robert tends to reference movies, Kathleen is more likely to cite poets such as Seamus Heaney or, her favorite, William Stafford. When she married Robert 36 years ago, her family was sure it wouldn’t last. “None of them bet on us past five years. I was too high-maintenance, too expensive, and Robert didn’t have any promise, as far as they were concerned. They didn’t know the real thing when they saw it. And I did.”

The couple always made family a priority. Their daughters, Clara and Chloe, were both at the Birchmere that night. Clara, who is 28 and lives in Nashville, is funny and self-deprecating like her dad. She helped manage the tour and was grateful for a chance to give back to her parents. “They did their best for me and my sister—all the time. I’ve seen a lot of people who that hasn’t worked out as well for in this business. I don’t think there’s a moment they took anything for granted.”

Keen is also uncommonly gracious toward his band. At each of the nine shows I saw him perform this year, he never failed to thank every member individually, along with the stage manager, the venue, and the sound guy. Whitbeck told me this wasn’t just for show. “The day I auditioned for Robert, he told me, ‘I pay my band salary. I want you to feel like you have a real job.’ ” Keen also provided health insurance and a retirement plan. During the pandemic shutdowns, he mortgaged his house to keep his band and team on salary, with benefits. “I don’t know anyone else who did that,” Whitbeck said.

As the tour wound down, it was hard not to think of what comes next. Keen isn’t quitting music, just the road. He hosts the popular Americana Podcast, in which he interviews artists such as Lucero’s Ben Nichols and the Suffers’ Kam Franklin, with Clara producing the show. Keen looks forward to spending more time on that project. There’s the album already in the bag, Western Chill, set to come out next year, along with an accompanying graphic novel and songbook. And he’s hoping to find ways to help young artists who are where he was at their age—talented but struggling to find a place in the industry.

But before this next chapter got underway, he had some unfinished business in Texas.

For Keen’s finale, he returned to his favorite venue, John T. Floore’s Country Store. He had a lot of history with Floore’s. Located in Helotes, fifteen miles northwest of downtown San Antonio, Floore’s is a honky-tonk and cafe with an outdoor stage in the back. Over its eighty years, the venue has hosted many of the biggest names in country music, from Patsy Cline to Willie Nelson, but the act that became most closely associated with it was Keen. He’d played countless gigs there over the years, including one that was recorded and became his best-selling album, 1996’s No. 2 Live Dinner. Now, over three nights of Labor Day weekend, Keen would close this part of his career on the stage that had helped launch it.

Tickets had sold out nearly instantly. They weren’t cheap, and there was a feeling that everyone who’d managed to make it to the show was a True Believer. The atmosphere was unlike anything I’d experienced at a concert—exuberance tinged with melancholy. Will Hurd was there one night, and so were many of the artists Keen had inspired. Some of the fans whispered about the possibility of former bandmates making a cameo, or possibly Lyle Lovett. But except for the addition of Lubbock legend Lloyd Maines on pedal steel, Keen chose not to pull out any tricks. He stuck to the gang that had persevered through the past few madcap months.

He did, however, invite one special guest to the stage. Reading from prepared notes, Keen addressed the audience, talking about the tour’s many challenges. “There was one thought that kept driving me throughout this rigorous ordeal, and that thought was branded on my brain in 1974, my senior year in high school. I’d grown up in Houston with dreams of being a cowboy.” He told the rapt crowd about his adolescent rodeo obsession. “I became a lifetime fan of a man that I consider to this day the greatest sports hero ever. . . . When he quit rodeo, he was at the top of his game . . . I thought that was the coolest, most dignified exit from anything a person could accomplish. I thought that if I ever had a moment of clarity like my rodeo hero, I promised myself I would follow his lead. At this time, I would like to introduce you to my hero and thank him for showing me the way.” Keen’s boyhood idol, Phil Lyne, walked onto the stage and took his place next to Keen as the crowd erupted. “He is here tonight to stand by my side, so you wonderful people could see this amazing man and know that heroes are real.”

Keen and his band played with everything they had. They served up the classics, they threw a few curveballs—deeper cuts such as “A Border Tale” and “Ride”—and Keen took time to pay homage to some of the artists who’d influenced him, covering songs by Steve Earle, Terry Allen, James McMurtry, Guy Clark, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Nanci Griffith. On the final night, Keen closed with his song “I’m Comin’ Home.” He rose from the chair he’d used onstage since early spring. The rhinestones on his suit sparkled under the lights, and he swaggered like a prizefighter, playing the late Jerry Jeff Walker’s guitar.

I looked around. This, I realized, is what truly sets Keen apart, what defines him more than Texas or his humor or even his storytelling—his ability to capture joy. I remembered something Kathleen had told me: “Happiness comes in glimpses.” For a moment, we all shared a glimpse with Robert Earl Keen.

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Road Can’t Go on Forever.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Bandera

- Austin