Garland native Caleb Landry Jones isn’t a household name quite yet—but he’s had memorable roles in movies and TV shows that long ago cemented his status as a celebrated “that guy” of cinema. The thirty-year-old’s face is tattooed on the memory of anyone who saw him play the creepy brother Jeremy Armitage in Get Out or the creepy boyfriend Steven Burnett in Twin Peaks: The Return. He’s simply too weird not to have made an impression.

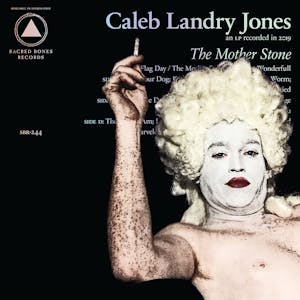

To no one’s surprise, that oddness extends toward other artistic mediums—and Jones’s debut album, The Mother Stone, is similarly unsettling. Out this Friday on Sacred Bones, the album is 65 minutes of rambling psychedelic fuzz that could easily be the background music at a haunted circus from which you may not escape alive. The video for the lead single “Flag Day/The Mother Stone,” which features a semi-nude Jones in a Marie Antoinette wig and clown makeup (that he also dons on the album’s cover), is no less menacing. But like other onscreen performances from the man New York Magazine once once referred to as “Hollywood’s go-to weirdo,” the music stays with you. And it prompts questions like: “What is this guy’s deal?” and “From what demented brain does this creative energy flow?”

Fortunately for us, the affable Jones was happy to elaborate over the phone about his creative process, how film informs his music, and the strange images he imagined as a kid listening to The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Texas Monthly: How’s your quarantine going?

Caleb Landry Jones: Oh, it’s going fine. I’m at my parents place in Farmersville, just outside of Princeton. So it’s nice out here.

TM: Is that the same place with the barn where you recorded a lot of early stuff?

CLJ: Yeah, my parents’ place.

TM: Tell me about putting the album together.

CLJ: I write a lot of music whenever I’m not doing anything. Because of acting, I wouldn’t get many chances to record. Then I’d be done for a few months or a month or a few weeks, and I’d come to Texas. And then the last ten years, it’s become more frequent that I’d write stuff while I was working, because I’d spent so much time away. Then I’d save it all up until I could come back to the barn and then I’d unload it all in the barn.

So this record happened in the same way. But I was writing songs, and then just more kept coming and more kept coming. And then I got to Los Angeles eventually and couldn’t leave LA, so I reached out to a friend of mine from the band Night Beats, Danny [Lee Blackwell]. And he’s a close friend and also he’s worked with Nic [Jodoin], the producer of the album, and his studio Valentine [Recording Studios]. So Danny put me in touch with him. And then Nic had some time one week that I could come in, and went from there. I was telling someone today that it’s like lighting a firework or something. We just kind of we lit the fuse and then stood back till it was all done.

So this record happened in the same way. But I was writing songs, and then just more kept coming and more kept coming. And then I got to Los Angeles eventually and couldn’t leave LA, so I reached out to a friend of mine from the band Night Beats, Danny [Lee Blackwell]. And he’s a close friend and also he’s worked with Nic [Jodoin], the producer of the album, and his studio Valentine [Recording Studios]. So Danny put me in touch with him. And then Nic had some time one week that I could come in, and went from there. I was telling someone today that it’s like lighting a firework or something. We just kind of we lit the fuse and then stood back till it was all done.

TM: So what was the songwriting process like? You say “they just keep coming.”

CLJ: Sometimes with songs, you’re just struggling to keep up with what your head’s telling you to write down. And then other times, I’ll find myself in the barn and I need to get out a feeling, but I’m bled dry of any thoughts of music or anything, and then forced something. Sometimes it comes from fiddling around on an instrument, and really wanting something to happen, and nothing happens. Sometimes something comes out of nowhere. And then you play that and then that leads to something else and that leads to something else and then before you know it, you got yourself a song.

TM: Can you describe the barn for me?

CLJ: Let’s see, I’m in here now. There’s a stove in there. There’s a whole lot of tools all over the place. Tools and tools and tools and tools and tools. And I’ve got my drums set in here, and there’s an old half a piano in here. And there used to be keyboards in here, but they’re all at the studio. So it’s a little vacant right now, mostly just tools at the moment.

TM: You come back there often when you’re not working?

CLJ: Yeah, yeah. Whenever I don’t need to be anywhere for any reason, I’m usually here.

TM: Were a lot of these songs inspired by dreams? They definitely feel dreamy.

CLJ: Some of the lyrics seem so out there that the only way I can explain it is like to say that they come from the same place that a dream comes from. A lot of the songs feel like they take place in reality, but then they take place in another reality, and then in a place where there’s no reality at all. I really like picking things up in the middle of places sometimes, or dropping in somewhere and not necessarily having any reference to anything else except for what came before it, and hoping that there’s some kind of logic that exists. And I hope that you can, as the listener, figure out for yourself what it is to you, whatever images it brings up for you. That’s perfect.

TM: Say you’re filming the new Twin Peaks or something, and so you’re in one creative headspace. Does an experience like that light anything up for you, musically?

CLJ: Big time. It’s a part of my life, and so it all goes into the music, just like everything I do. Certain aspects go into certain films, and certain parts of your life you can’t separate. It’s been really great as an entertainer to be able to have those things running at the same time. So it all feels like one train. But when I did that show that was also the year that I’d been a part of more projects. I think I did seven or eight acting jobs. And I’ve never done anything like that before. So I think by the time I got to make some music, it was just … all coming out so fast.

When I did [Twin Peaks], I didn’t bring any instruments with me because I told myself that the character didn’t play music. So all I brought was a harmonica, because if he was going to play music, it is going to be through something like this. And I used that quite a bit. It’s a way to make myself feel better, or get myself in a different mood; hop on the train tracks and play a little. You start feeling different.

TM: In terms of creative process or output, what do you think music provides that acting doesn’t?

CLJ: I think film and television uses music in a way that can be quite profound and elicit great emotion. And other times it can be misused greatly. Half the time I find that the audience member, the person listening to music at home, will probably create visuals ten times greater than whatever image somebody is going to put the music to. But music is its own kind of language. Music on its own, without any visual representation, is more powerful, like reading a book by yourself, and you create those visuals based on the information you’re given.

I’m so glad there wasn’t a film for Sgt. Pepper’s that I saw first. I’m really glad that [initially] happened in my head. And then as I got older, I saw what they looked like and I saw Yellow Submarine. When I saw that movie, I felt like I got to know the image that they were portraying a little better. But for a while, that image solely existed for myself, with my father, my brother in the car on road trips. And my brother and my father, they had their own things in their heads. And I had my own things. And I remember being conscious that this was creating something in my head that I was scared to share, because I didn’t know if it was healthy or if it was okay, because some of the images were weird and strange.

TM: What kinds of strange images?

CLJ: I remember listening to [The Beatles’] “A Day in the Life,” and the guy in the car accident … as a kid, I thought he’d blown his brains out, you know? I thought he’d shot himself at the stoplight, with other people behind him. And so that was a really strange image. I don’t think that’s what happens in the song, but in my head…you know. And so I remember like “Fixing a Hole” and this idea of this man is staring at this hole for four hours, thinking about fixing it but not fixing it, and then fixing it. I mostly remember these strange feelings I got from songs at the end of the record.

There was there was some darkness in [Sgt. Pepper’s] that scared me to death. But at the same time, I related. Like the strings at the end? It was so overwhelming for me, it’s like a fever dream. It was just anxiety overwhelming me. It was a feeling that I have so often. And I didn’t know that you could re-create these feelings in music, that that was allowed. And so to me they were quite wild, the patterns within the music, and yet very on the nose and catchy. Sometimes it felt very simple, but then when you learned how it was played it seemed quite complicated. But when I was eight years old, I just thought that was just a remarkably wild and strange record. I hadn’t had a piece of music evoke so much for me. There’s so many different parts of me, I suppose.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.