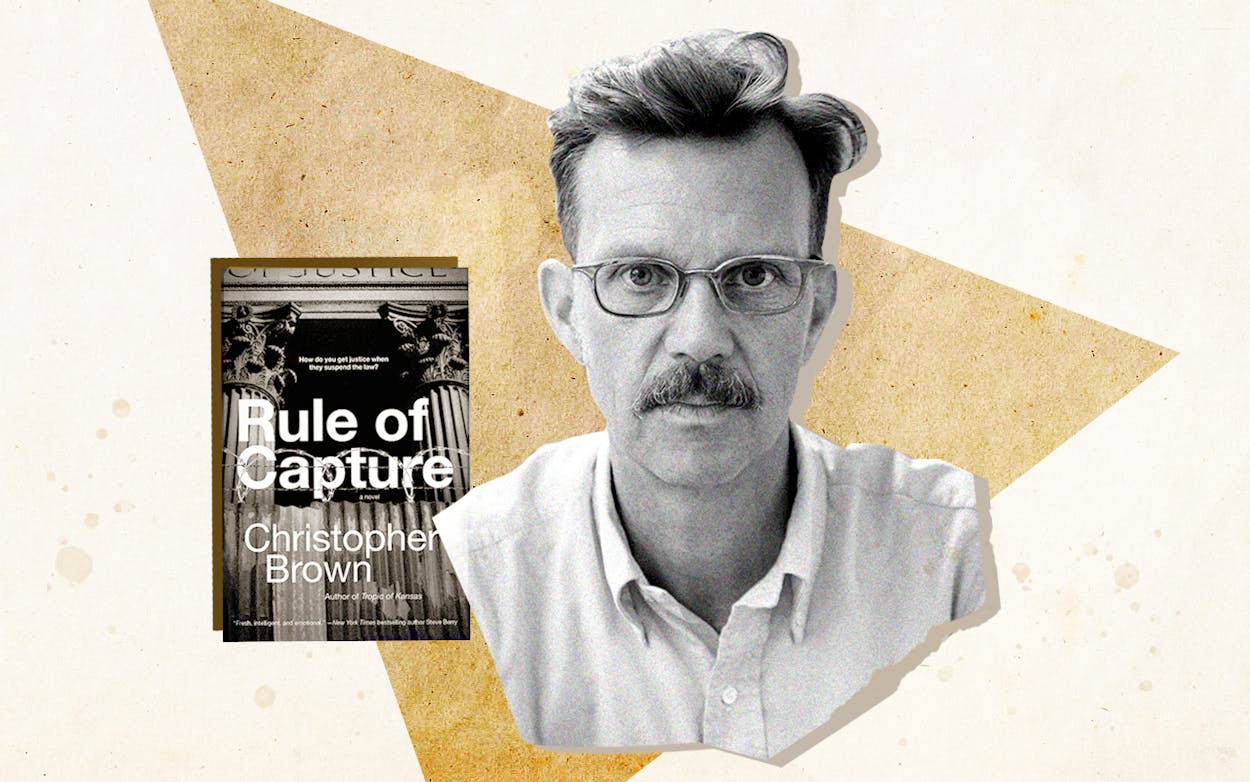

The Austin author and lawyer Christopher Brown’s second novel, Rule of Capture (Harper Voyager), is a legal thriller set in a bureaucratic dystopia as grim as anything imagined by J.G. Ballard or William Gibson. The novel’s protagonist, Houston public defender Donny Kimoe, works at a classified terrorist court, which is part of a Patriot Act-like clampdown on insurgency that follows a humiliating war against China and the rise of an “America First” government. More than war, however, it’s global warming that has remapped the country’s borders and created various uninhabitable regions, forcing vast numbers of people into stateless itinerancy—those who often comprise Kimoe’s roster of “terrorist” clients.

For all its menacing atmosphere, the novel’s setting is not an imaginary, far-future Gotham, but a version of Houston that is in many ways only a slight exaggeration of the city we know today: afflicted with devastating traffic jams and floods, scattered fallout zones, and FEMA camps. Houston, in the author’s apocalyptic imagination, has become a balkanized dystopia and central political player in a fascist national regime, a twenty-first century city “that had been made from the idea of the things you take from the ground you seize, a city whose ethos had been the motive engine of the wars and deals that had kept it alive, even as much of the country around it began to wither from the way that model had drained the fuel tank of the future.”

Like Brown’s previous novel, 2017’s Tropic of Kansas, which is set a few decades later in the same world, Rule of Capture is a genre page-turner with intellectual ambition, rendering its speculative plot about Amerika’s war-machine with themes of disaster capitalism, the Anthropocene, and techno-fascism. Texas Monthly recently spoke with the author about the politics of disaster, Houston’s remix culture, and the zany auteurism of the “Texas Hammer.”

Texas Monthly: The book’s title, Rule of Capture, refers to an old English common law that says that a landowner has ownership over all natural resources on his property, whether it be oil, water, animals, etc. You also write at length on some of the country’s other bedrock principles, like the Discovery Doctrine’s law of conquered territory and the rules of martial law, which has often been declared within states to repulse workers’ strikes and civil rights marches. How much research did you do into colonial and state law to develop the book’s realistic legal codes?

Chris Brown: I tried to construct my dystopian legal system from real law as much as possible. I did a ton of research, most of it at UT-Austin’s Tarlton Law Library. I read transcripts from the Kafkaesque tribunals at Guantánamo, oral histories of the lawyers who provided pro bono defenses to the detainees, materials on the Baader-Meinhof trials and other terrorist prosecutions in 1970s Europe, and the case law from stateside military trials of civilians and spies from the Civil War to the Cold War. I found a whole section of treatises with titles like The Practical Administration of Martial Law—how-to guides from the period when, as you note, governors frequently invoked that emergency power to suppress labor actions. In Texas, the governor once declared martial law in a single county to enforce production caps on oil wells. I made the Coast Guard into FEMA Stormtroopers after learning that they’re the only branch of the armed forces that can be lawfully deployed for domestic operations. I dug into some of the far-out provisions of the Texas constitution, especially the military forces under the governor’s control, and wondered how far those powers might be stretched in the right circumstance—if, for example, you had young people taking to the streets the way they are in 2019 Hong Kong. One of the first reader reviews I got was from my accountant, an Army Reserve officer who leads joint operations with FEMA in Texas. He said my climate change-induced martial law no-go zone along the Ship Channel was the most realistic dystopian scenario he had ever read—something I was simultaneously delighted and horrified to hear.

TM: I was fascinated by the way in which you re-envision Houston as the center of political power in a future world-order rather than its traditional position as a regional outlier.

CB: As I was beginning to think about this book, I happened to watch Rollerball, the 1975 movie starring James Caan as a gladiatorial professional athlete in an imaginary 2018 Houston where, as the opening titles explain, “nations have bankrupted and disappeared, replaced by corporations.” There’s not much of the real Houston in that movie, but it got me thinking about the ways in which Houston works as both dystopia and utopia. And then, when I was on tour for Tropic of Kansas, I did a reading in Houston the night Harvey blew in and got out that morning just in time to avoid being stranded on a submerged freeway, a scene straight out of some 1960s J.G. Ballard sci-fi nightmare of the drowned world.

Houston to me is the most authentically twenty-first century city in the USA, and at the same time, the one that is most closely yoked to its own past. It’s more like the Los Angeles of Blade Runner than the real L.A. will ever be, somehow managing to make endless sprawl feel like maximum density, a totally globalized multicultural cityscape of ubiquitous advertising and looming corporate towers, a place where the weather always feels like nature is fighting back but mostly losing.

TM: What is it about Houston that makes it a cautionary tale or dystopian model for the future?

CB: Houston scared me at first, as a young Midwesterner finding his way through the flare-offs and freeways lined with crazy billboards, scary nightclubs, and scarier gun ranges. But the more I got to know it, the more I loved it.

The Houston of Rule of Capture is the Houston of Enron and The Big Rich [Austin writer Bryan Burrough’s 2009 book about the Texas oil industry] channeled through an imaginative prism that riffs on the Houston of Rushmore and Donald Barthelme’s short story “The Indian Uprising.” And maybe more than anything, the Houston in my book is the lawyers’ Houston—a culture where the white shoe corporate firms invented greenmail, the plaintiffs’ bar figured out how to export the high-stakes contingent fee model to merger fights, and unembarrassed self-promoters like “the Texas Hammer” [personal injury lawyer Jim Adler] are so inventive in their commercials that they turn the lawyer ad into a form of art.

But more than anything, Houston was the ideal setting for an effort to use the tools of speculative fiction to tackle big issues about how the legal system defines our relationship with the natural world, and how the greener future we need to build can only be built by rethinking those rules. I’m interested in imagining a future where wild nature and the human city truly coexist, and Houston is the best real example I can find—and a perfect place to imagine a more intentional remix along those lines. But to find the path to that better future, you have to confront the darkest things about the present, and the past. Including the blood that’s in the soil along with the oil.

TM: Your dystopian Houston is not only a dark, balkanized industry city but also the home of an alternative underground world of jazz-inspired hip-hop artists, S&M/transgender clubs, and a new synthetic drug trade. Does the real city have such a transgressive history?

CB: Houston is a remarkably fertile field for artistic and literary innovation, and that’s one of the qualities that made me fall in love with the city. It was only after I had spent more time there that I realized how many innovative artistic works that I loved came from Houston. Writing this book, I very deliberately wanted to imagine an American version of Weimar Germany—a nation whose humiliating defeat in World War I opened up the parameters of the possible and engendered a flowering of new ideas [such as agit-prop theater, atonal music, and expressionist film]. And Houston makes a great alt-Berlin. The jazz-inflected hip-hop artists are already there in real life, people like Jawwaad Taylor, Perseph One, and the musicians around David Dove’s Nameless Sound project—many of whom studied under electronic music pioneer Pauline Oliveros, a Houstonian who managed the remarkable act of turning the accordion into an instrument of the avant-garde. I reread Lance Scott Walker’s amazing book Houston Rap, which really digs into the DIY roots and political edge of Houston’s unique underground music culture, and listened to a ton of early DJ Screw tapes. I reread the section of Tracy Daugherty’s biography of Donald Barthelme, Hiding Man, in which the author returned to his hometown to start the creative writing MFA program at U of H—and I imagined an alternate reality in which that Houston architect’s son stayed home and became the mayor, designing fabulist freeways instead of surreal short stories. After I finished the book, I came across Pete Gershon’s Collision, about the wild ’70s and ’80s contemporary art scene in Houston. There’s something there, something really unique about Houston, that produces these kinds of creators. Even Wes Anderson, whose work embodies that weird preppy whimsy and avant-wonder that the more privileged parts of Houston produce. Something about that “why not?” Texas attitude and the absence of a curated critical establishment lets people make the art they want to see. At least half of the artists and musicians I know in Austin are Houston transplants. Houston is smart, and cool, and crazy, and free, and it’s a fun place to write about—even when you are making up your own mirror-world variations on it.

TM: Both of your novels feel prescient and familiar in a way that is discomfiting, much like J.G. Ballard’s work, which describes societies both of the near-future and possible present. How do you negotiate between futurity and the contemporary when you write science fiction?

CB: I’m trying to write a science fiction that remixes the material of real life to show truths that conventional modes of realism cannot. I’m not so interested in futurity as I am in altering the aperture through which the reader views the world in order to let them see it though fresh eyes. If you unmoor the reader from the normal markers of identity and experience just a little—put a fun-house mirror up to the world—you can entertain them with imaginative play and also leave them thinking about the world around them in a different way after they put the book down.

Dystopian novels often purport to be—or are assumed to be—set in the future, to suspend disbelief in their fantastical elements. But the reason books like 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale get called “prescient” isn’t because their authors were practicing predictive futurism, but because they reported accurately on the character of the contemporary world they saw. The same lens that novels use to explore what happens to the dynamics of a family when something bad happens can widen its aperture to explore what happens when some fundamental aspect of society— politics, environment, technology—is altered or some latent tendency in our natures is allowed to express itself. All novels are set in alternate worlds, even if most writers only invent the people that inhabit them. Dystopia just expands the scale of the alteration.

TM: Rule of Capture makes many references to a Trump-like regime, an expanding far-right, the breakdown in legal norms and international diplomacy, conflicts with China, and an ecological disaster. How much of the book had you laid out before Trump’s election?

CB: The incipient corporate fascism in Rule of Capture is something I invented for my prior book Tropic of Kansas, which actually takes place later in time, after that regime has fully taken control. And when I wrote that, it was in 2013-14, when Trump was not even on my radar screen. But that idea had been kicking around for a long time in certain circles—that there’s no better qualification to run a country than to have run a company. That was a big part of the narrative behind Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign—the private equity turnaround guy who would turn around the whole USA—and both Presidents Bush. I wanted to explore what that idea would be like in real life—informed by my own experience as a corporate lawyer, which taught me that corporations are not democracies, they are dictatorships, places where free speech does not exist and the person at the top gets to “axe” his or her enemies. I also wanted to bring out some of the ways in which the America I saw in that period was looking a lot like what we imagine as “third world”—if not post-apocalyptic, especially in the degenerating heartland of the Midwest where I grew up. When I was done, I actually put the book aside for a few months thinking it was too implausible—only to see the real-world headlines rapidly start to catch up as 2015 unfolded.

TM: One of the phenomena you explore extensively is the growth of disaster capitalism—a term popularized by Naomi Klein’s book The Shock Doctrine about the infrastructure of post-war and third-world redevelopment—but which occurs in your book after the ecological collapse of the U.S. We’ve already seen this begin to happen in the Gulf states with Hurricane Katrina, the Deepwater Horizon, and the Houston floods. Did you do any research into the disaster-recovery industry and were you surprised by what you discovered?

CB: During the Deepwater Horizon crisis, I visited Houston one weekend. And on Saturday night I found myself in the bar at the Four Seasons Hotel downtown, amidst a mob of what I realized were a crowd of disaster capitalists blowing off steam as they tried to plug the hole in the world and make a fortune in the process. It was like some crazy J.G. Ballard version of a Western, so quintessentially Houston. You knew that as the apocalypse unfolds, Houston will make good money right up until the end, and party away a fair share of it.

A few years later, I went to Houston to attend a different kind of disaster capitalist event—the first installment of Space Com, a trade show devoted to the commercialization of space. There were venture-backed hucksters pitching mineral rights in asteroids, Chamber of Commerce types promoting Spaceport Houston, and some more far-out sorts planning colonies on Mars. And, again, you could see what a perfect cultural platform Houston provides for that kind of thinking. Roughnecks on the moon? Why the hell not?

TM: Did you see any evolution or revolution in Texas politics in the next generation?

CB: I’m not an expert on Texas politics. But I do know a fair bit about Texas ecology. My family and I built our house in an East Austin brownfield where a petroleum pipeline once ran, and through our work restoring that acre to blackland prairie, we have become very involved in the wider restoration movement. Texans are very good at making the land work for them, at capturing the value it holds and selling it to the highest bidder. But they also love the land in a unique way, and I believe people like the green roof designers at Austin’s Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, the visionary family behind the Native American Seed farm in Junction, and the folks behind the restoration of Buffalo Bayou in Houston portend a green future for Texas, one that helps bring back the wild that’s right there in the liminal spaces of our cities, and in the process reinvigorates the idea of the commons that I think our hardscrabble ethos has mostly lost. And to me, there’s no more important political issue in the early twenty-first century than what kind of ecological inheritance we bequeath our grandchildren. I’m optimistic on that front, maybe because I have witnessed the resilience of nature—and the resilience and good nature of Texans.