This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

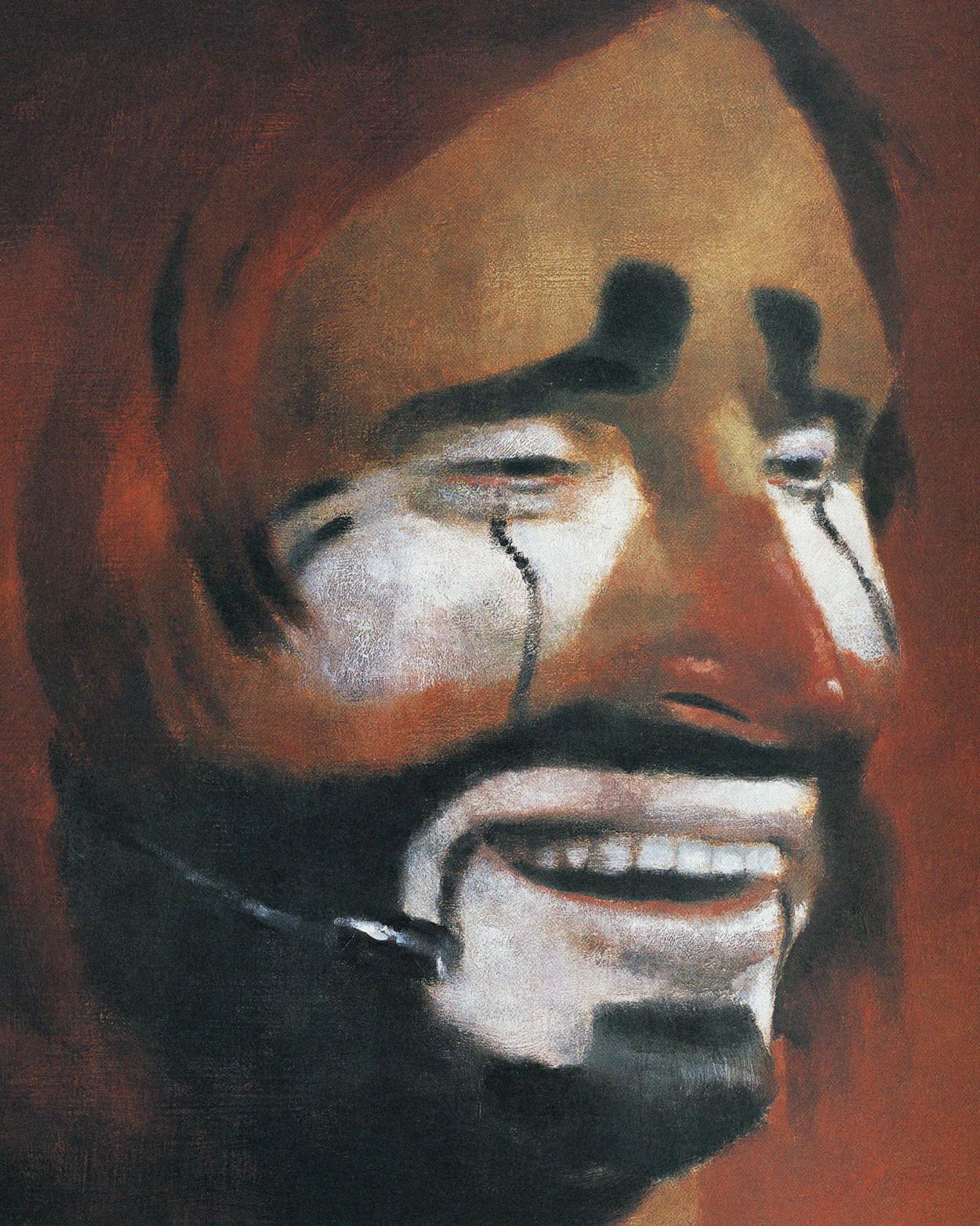

In the sultry glare of the rodeo ring, Lecile Harris is working a crowd of six thousand. He limps in the spotlight, famous to the fans in his tramp makeup and cheesy red wig. One minute he roams the arena like Groucho Marx, striding low in his baggy pants. The next, he kicks at the dirt and grumbles into his wireless microphone like a genial maniac carrying on a public dialogue with his demons. For more than three decades, throughout Texas and across the chigger latitudes, this is how Lecile (pronounced Lee-sill) has made his living: first as a hillbilly bullfighter, now as a cracker Benny Hill, one of the last pure burlesque comics in America.

On this night, Lecile and his crew are at Harper Stadium in Fort Smith, Arkansas. It’s Memorial Day, 1991—the first night of the Old Fort Days Rodeo. Lecile’s sidekick, Rudy Burns, waddles around the ring in his barrel like E.T. trying to get back to his spaceship. The blue aluminum barrel gets banged up daily, so Rudy travels with cans of matching blue paint to touch it up. A bull crushed this one last week, and he had to open it back up with a hydraulic jack.

“A bull is a turf freak,” Lecile told me that morning. “As soon as he enters the ring, he wants to prove he owns it. He’ll charge the rider and lunge at the bullfighters. When he’s really pissed, he tries to hit the barrel.” A barrel man has to brace himself inside, curled like a fetus against the rubber-lined walls as bulls knock him around the ring. Rudy used to fight bulls himself, but he was a tough young Cajun then. The current arrangement is his “retirement plan,” he says. “When you’re too old to fight the bulls, you move into a barrel.”

Most bullfighters drift out of the game in their thirties. Rudy was 35 when he quit. Lecile hung on much longer: He fought bulls until 1988, when he was 52. But long before that, he was doing comedy, much of it verbal. That was something new.

Until twenty years ago, rodeo comedy was pantomime. A clown’s job was to police the ring and save the bull riders. Then he’d do what bookers called a “country act”: A stubborn-mule bit or some stunt with an exploding clown car. A clown might get off a stray line or two, but the announcer would have to repeat it over the loudspeaker. That mangled a lot of gags. But one night in 1975, while working for the Longhorn Rodeo Company in Detroit, Lecile clipped on a wireless microphone and began testing the kind of jokes that modern audiences, who were used to TV, had come to expect.

Inside the arena, Lecile is a chattering hillbilly id. His announcer, Phil Gardenhire, feeds him straight lines, then scolds him for his wisecracks with the voice of square authority. Lecile pouts and whacks his straw dummy, mumbling “Yessir!” and “Nossir!” There’s no set routine. Lecile doles out his gags to fill the time between rides, never taking his eye off the bull chute. “His timing is the best,” says Rudy. “Some clowns will be telling a joke and all of a sudden the gate opens. Well, your crowd don’t know whether to listen to the joke or watch the ride. But Lecile always knows what joke will fit.”

Lecile’s got a long delay now, so he’s on a roll. He says he couldn’t get any sleep last night. Some girl kept pounding on the door of his motel room. He says he finally had to get up and let her out.

He says he took his wife to New York, but she got mugged. He says it wasn’t all bad. She discovered she liked to be frisked. He says she liked the frisking so much that when her money was gone, she gave the mugger a check to frisk her again.

He says he tried to bring his wife to the arena, but the gates weren’t big enough to let her in. He says he took her to town and got her a brown dress, but people thought she was a UPS truck. On it goes.

He ambles over to the side of the ring. “By the way,” he says, his voice twanging, “did you know I’m selling pantyhose?”

“Lecile!” the announcer drones. “You’re selling pantyhose?”

“Yessir, I’m wholesaling pantyhose.”

“How much do you charge?”

“Three dollars a pair. Fifty cents installed.” The crowd laughs, and Lecile points into the audience with his broom. “That blond woman there—I’d like to install a pair on her. In fact, I’ll loan her the fifty cents.”

The crowd eats it up, and Lecile leans on his broom, gawking like a big-eyed Gomer who’s never seen a city girl before, let alone a grandstand full of six thousand people.

The first time, in 1955, it was just a lark. Lecile and a friend drove a ’34 Chevy to a backyard rodeo near their home in Collierville, Tennessee. Lecile rode a bull that day—not too well. At six five, he was too tall; bull riders need a low center of gravity. But he loved riding and haunted rodeos the rest of the summer. To earn money for entry fees, he hired himself out to protect other riders. His high reach made him a natural for untying cowboys hung up on their bull ropes.

At a rodeo in Sardis, Mississippi, the regular clown didn’t show, and Lecile ended up in the ring with a shoe-polish beard, his nose reddened with lipstick, and a gunnysack cape. “Pretend you’re a matador,” they told him. “Just keep running in circles.” They should have said tight circles. Lecile ran in big ones, and the bull kept chasing him down. On the third night, a bull pinned him against a fence and tossed him into the crowd. He was getting twenty-five bucks a night. “When I was hot, I really loved to fight bulls,” he recalls. “If I heard somebody had a bad bull somewhere, I was liable to go over and fight him for nothing. To move in on a bull, to touch his face, his head, and get out again—that’s like hitting a home run for me.”

But Lecile moved out of neighborhood rodeos quickly. Preston Fowlkes saw him and signed him up for the Fowlkes Brothers Rodeo out of Marfa, billing him as “the Original Bull Dancer.” Lecile began to blast his audiences with rock and roll while he boogied in the ring, inviting bulls to gore him. A perfectionist, he set his own standards. “There were always two times when I felt I had failed,” he says. “One was to have to limp or be carried out. The other was to lose my wig in the arena.”

Lecile was already a rodeo legend by 1975, when producer Sam Lovullo hired him for the cast of Hee Haw. His years on TV helped him craft the kind of act he now tours with 25,000 miles a year. He has a dancing raisins act, a monkey act, an exploding golf cart. The humor is stuffed-club-in-the-pants material. It’s Abbott and Costello meet the Bull. It’s not Noel Coward. But it’s perfect humor for a venue where the humorist may be hit at any moment by a two-thousand-pound Brahman bull and have to be carried out, leaving his wig in the arena.

As soon as the rider is ready, the clowns get set to earn their pay. Rudy pops into his barrel. The bullfighters flank the gate. The rider nods, and the gate swings wide.

The grandstand shudders. A cloud of flies buzzes off the crossbred Brahman’s hump, and the animal kicks his way out of the chute. The crowd roars as the bull enters the spotlight batting the rider up and down like a rubber ball on a paddle, then throwing him before the buzzer sounds.

Now the clowns move. Bulls are color-blind, but they’re suckers for motion. Lecile trucks to one end of the arena. Rudy wobbles about in his barrel like a drunken tank. The bullfighters feint left and right, rags and neckties fluttering from their belts like matadors’ capes. The bull, torn between targets, picks the barrel and plows into it, tumbling it with Rudy inside, his head tucked between his knees in case a stray horn gets in; he once lost a row of teeth by not doing that.

One of the bullfighters, Donny Sparks, tears across the ring and rolls the barrel. Then he rights the barrel and starts circling it. “Screwing the bull into the ground,” clowns call it. By now, the rider is safely out of the ring.

This is the rodeo clown in his classic role: protecting a cowboy and making a show of it. “See, a bullfighter was put in clown makeup because people cringe to see a man get hit by a bull,” Lecile says. “A clown isn’t a real person to them. It takes the edge off when you get hit. They say, ‘That clown got hit. Thank God he didn’t hit a man.’ ”

Out behind the grandstand, the clowns dress on the second floor of a cinder-block building, in a windowless cell with sulfur-colored walls. Near the door, a row of Lecile’s freshly laundered shirts hangs neatly on a rack. His size-23 golf shoes sit on the floor alongside other clownwear, and his dummy leans against the wall like a large uprooted scarecrow. A tableful of cheeseburgers, french fries, and greasepaint is reflected in a long makeup mirror where Rudy paints dots and dashes on his face. Donny Sparks draws a butterfly wing on each cheek. Bullfighter Bryant Nelson, late to arrive, grabs a burger and talks to Lecile’s son Matt.

Lecile’s in a tiny bathroom next door. He’s not wearing any makeup yet, and his shirt is off. His chest is bandaged. “My ribs look like a damned beanbag, don’t they?” he says with a laugh. But it’s his swollen arm that he’s nursing now, in a sinkful of steaming water. A spill several weeks ago caused an infection and raised a funny spur on his elbow, though it’s more nuisance than injury. “I’ve fought bulls on crutches,” he says before dressing and heading out to the ring.

“If you fight bulls, you’re gonna get hurt just about every week,” one bullfighter says after Lecile has left. Of course, some nights are worse than others. One of the worst came for Lecile the previous summer in Reno. He was made-up but between acts and walking out of the ring when a bull caught him and rammed him into a steel fence. It crushed his ankle, broke his pelvis and three ribs, dislocated his shoulder, and tore up his knee, which had just been repaired after an earlier scrape.

“If Lecile had been fighting bulls it wouldn’t have happened,” Rudy says. “He’d have been in a different frame of mind. ”

“Yeah,” says Matt. “It was just a freak deal.”

“I saw the panel that the bull ran him up against,” Rudy says. “There was a steel pipe in it about an inch thick, and now it’s bent. It looks like a piece of muffler pipe.”

“It was a new bull,” Matt says. “He was pretty green. One of those bulls that just runs the fences, looking for somebody to hook. ”

“They hollered at Lecile, and he saw the bull,” Rudy says. “So he took off running. But he bumped into the announcer. That slowed him down. The bull just picked him up on his horns and was running with him. Crushed him against the fence. Wasn’t nothing Lecile could do.”

“It really was a freak deal,” Matt says.

“Sure was a freak deal,” Rudy says, getting up to go.

“Shoot,” says Bryant. “Freak deals happen every day. ”

On Saturday, the last night of the rodeo, ESPN is setting up to tape the show. Everybody wants it to be good—especially after Thursday’s fiasco. That night, the bullfighters all drew “pups”: bulls too young to know what’s expected of them in the ring. Three of them did little more than attack the clown dummy, and one actually ran helplessly around the ring, looking for a way out. Bryant chased him, desperately doing jumping jacks to get his attention, but it only seemed to alarm the bull more. All the clowns wanted to wear bags over their heads when they left that night.

For Saturday, they want experienced bulls. A bullfighter’s no better than his draw. You don’t get points if the bull won’t give you action.

Although it’s late evening, the temperature is still in the high nineties as the clowns straggle out to the arena for the fights. Lecile’s in the lead, laughing loudly. Rudy rolls his big, gold bullfighting barrel, made of heavy-duty welded steel. The lightweight blue barrel, good for the riding events, is too easy for a fighting bull to toss up into your face.

Behind them comes Donny Sparks. He and his brother, Ronny, make up the only twin bullfighting team on the pro circuit. The Sparks twins, from Texarkana, barrel jump bulls and barrel hop them. They leap over bulls flat-footed. For the past several years, they’ve both been ranked among the top six bullfighters at the Las Vegas finals, competing for half a million dollars and a gold championship belt.

Usually, you can’t tell the Sparks twins apart, though the other clowns say they can. Ronny’s more athletic, they all agree. Donny’s faster. Ronny thinks it’s the other way around. He thinks Donny’s smarter too. No one knows what Donny thinks. He doesn’t talk as much, although Ronny thinks Donny talks more.

This is the sort of problem you get into with twins. But tonight, you can tell them apart. Donny’s the one in makeup and soccer gear, ready to fight a bull in the ring. Ronny’s the one on crutches.

Ronny Sparks was hurt in April at a rodeo in Ardmore, Oklahoma. He was doing a barrel hop. That’s where you leapfrog the barrel at the moment the bull hits it, launching you and the barrel in a nice three-stage maneuver. It’s slick when it works, but it didn’t work for Ronny that night. A Mexican fighting bull, whose horns had been improperly tipped, impaled his leg on the barrel. Now Ronny is spending the rest of the season talking about bullfighting at local high schools.

Unlike Lecile and Rudy, you don’t get any funny business from the Sparks brothers. Inside the ring, Donny is a master of concentration. Outside, he speaks with the passionless lingo of a jock. The bull he’s facing tonight, he says, is a “fierce competitor.” For the Sparks brothers, who were athletes in high school, bullfighting is just another sport.

Rudy doesn’t think the younger bullfighters will ever become clowns. They’ll fight bulls until they’re 35 and then look for jobs. “These younger guys don’t think funny,” he says. “Guys like Lecile and me, we think funny all the time. Shoot, probably every doorknob in that dressing room upstairs has toothpaste on it. ”

“The younger guys have a macho air about them,” Lecile says. “I always made my bullfighting funny. The ultimate was for me to get into a hairy situation with a bull and get a rider out and do a piece of comedy. But back then, you had to do comedy and fight bulls. Now you’ve got your bullfighters, your barrel men, and your comedy people. You hardly ever see anyone do comedy and fight bulls.”

The Sparks twins call Lecile “Pops.” Back home in Texarkana, there’s a photograph of the three of them taken a quarter-century ago. Lecile is in his clown getup, with his droopy mouth, red nose, and greasepaint beard. The twins, three years old, are sitting on his lap, bawling. Lecile, a scary clown and a friend of the family, was not yet their hero. “They watched me until they got old enough to get in there and then I started coaching them,” Lecile says proudly. “They’d come and show me their tapes. Even now, they bring me a tape and say, ‘Okay, what did I do wrong there?’ ”

In Lecile’s heyday, there were no tapes, no big prize money, no cable TV exposure. That all came too late. But still, for this man who has let bulls run him and cripple him for more than thirty years, who’s now held together with Ace bandages and steel pins, the Sparks brothers are alter egos. “I live through them,” he says. “Whenever one of them makes the finals, hell, I’m there.”

Brad Holland is an artist and writer who lives in NewYork.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics