This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

What is most striking about Robert Benton’s new film, Nadine, which is set in Austin in 1954, is that Texas doesn’t mean anything. Here is a Texas filmmaker revisiting the same era that gave us Giant, Hud, and The Last Picture Show, all movies that draw deeply from the wellsprings of Texas past and Texas future. But as I watched Nadine—a halfhearted murder story and get-rich-quick mystery about the wife of a bar owner who is failing in business and love—what I felt most strongly was the absence of consequence. Nadine (Kim Basinger) and Vernon (Jeff Bridges) Hightower are true Texans, all right, but one does not read in them the death of the frontier or the coming of the oil boom or the rise of urban culture. The currents of history do not stir.

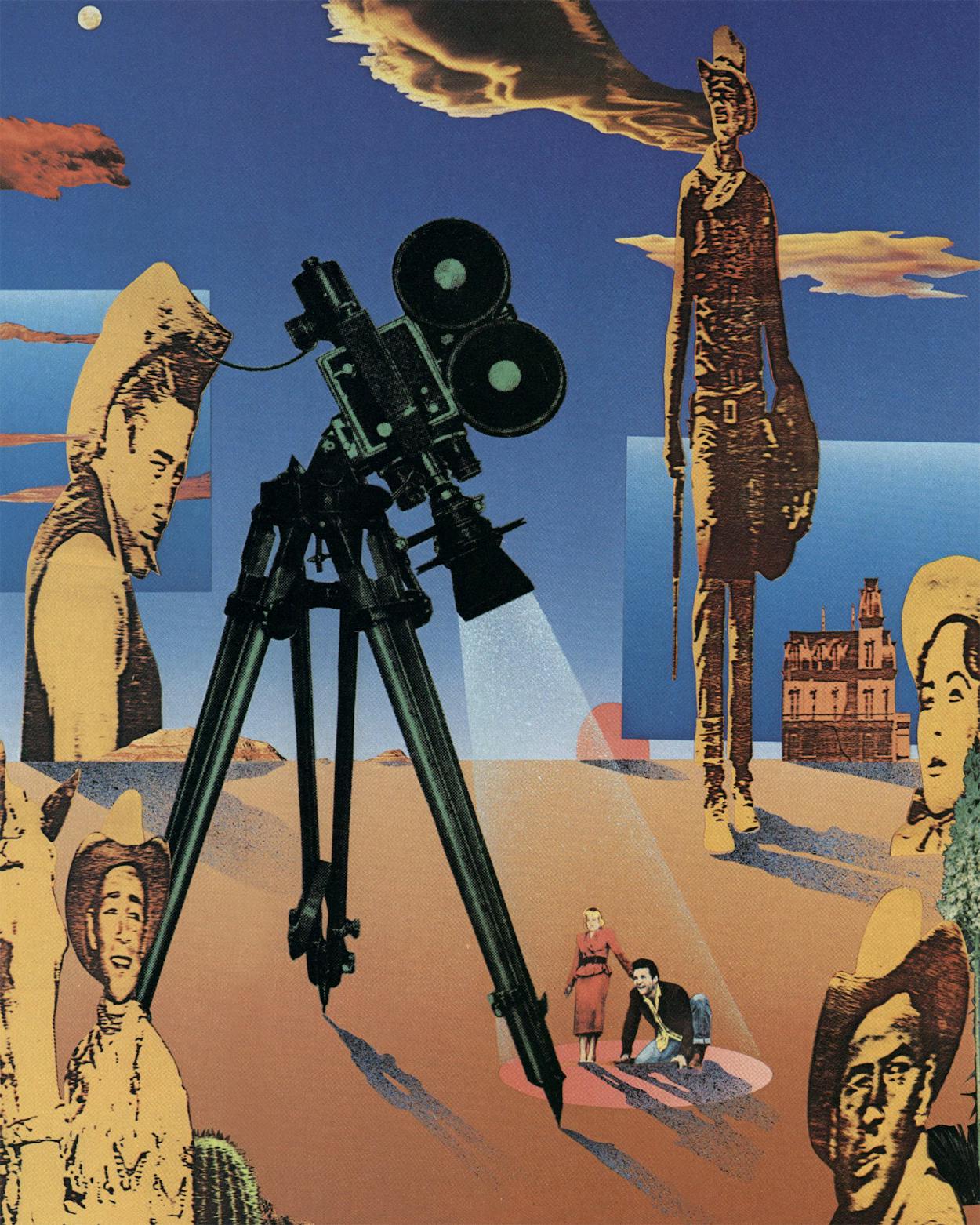

Now, of course, why should they? In Hollywood until recently, “Texas” was not a real place. It was a symbol for the unbridled West, where men are free to be myths. It was a playground for the American frontier legend, made over again and again in the westerns of John Ford and Howard Hawks. “Texas” was an arena of the mind, where a man came face to face with death and destiny. It was the same emotional territory as the wilderness of Judea, only in “Texas” God was absent, and man was left to fend alone.

Seeing those movies made me feel special as a Texan, but in a fraudulent sort of way. I imagine that every Texan—at least every Texas man—has experienced the dissonance of not being who he is supposed to be, of failing to live up to the legend. One goes through life being John Wayne, Jr. I had the chance to reflect on this phenomenon once in Egypt, when I went horseback riding near the Pyramids. I was given a rearing Arabian stallion that was brought to me by three terrified handlers. The horse’s name in Arabic was Murderer, and he hadn’t been ridden in two years. Because I was from Texas, the handlers assumed I could ride him—which I did, about halfway to Libya.

The Kennedy assassination abruptly ended the heroic era of “Texas.” After that, the state became a symbol for what Hollywood felt was wrong with America—it was violent, hateful, crude, and alarmingly dangerous. “Texas” was Slim Pickens as Major King Kong, riding the hydrogen bomb to apocalypse in Dr. Strangelove. “Texas” was the rednecks in Easy Rider, who couldn’t tolerate hippies and, lamented Jack Nicholson, liked to cut their hair. Now, when the movies came to my state, they weren’t looking for the good; they were looking for the evil. In the Zoroastrian universe of Hollywood, “Texas” was all one or all the other.

It wasn’t until Hud in 1963 and Midnight Cowboy in 1969 that the movies found the Texas I knew. I was teaching English at the American University in Cairo when Midnight Cowboy came out, and I took my class to see it. The movie opens on the Big Tex Drive-In in Big Spring, where Joe Buck (Jon Voight) has absorbed his dose of the myth, which he tries to live out by wearing movie-cowboy clothes and then by seeking stardom in New York. To me, Midnight Cowboy was exactly about the neurosis of wanting to live up to the myth. I came out of the movie recharged and excited, but I noticed my students were spiritually shaken, almost despairing. For the first time I realized how much the rest of the world valued “Texas,” what a rich legacy it was, how universally appealing was the myth.

“Texas” has its own geography, which figures into the mythical dimension. When we’re in “Texas” the actual film may be shot in Monument Valley, Utah (Stagecoach, The Searchers), or in the rolling Canadian wheat fields (Days of Heaven). In The Alamo San Antonio is perched on the banks of the Rio Grande. Paris, Texas, is in the pastoral Red River country, but Paris, Texas lies in the barren western desert. The disjunction between movie Texas and real Texas continues even in modern trash, such as The Swarm, in which a train crosses a range of mountains to enter Houston.

The antimythic Texas movies make a point of showing just how plain the place is, how spare and forbidding, and yet the odd truth is that the real Texas landscape on film is evocative and even mythic despite itself. The scene at the stock tank in The Last Picture Show, in which Sam the Lion is talking to Sonny about how beautiful this godforsaken landscape is, jumped off the screen into my subconscious. I too could see the beauty—it wasn’t pretty, but it was haunting, in a way. The now familiar ironed-flat prairie of Tender Mercies, 1918, Places in the Heart, and The Trip to Bountiful—all shot near Waxahachie—has become an existential tablet upon which man works out his spiritual needs. Perhaps Texas really is a place that exists more fully on film than in life. No doubt that is one reason there are scarcely any exterior shots in Nadine and only one brief glance at the countryside. It is a way of smothering the myth.

As a viewer, I’ve come to expect that when a movie is set in Texas, there must be a darn good reason. It is either playing into the myth or playing against it. But Nadine is only the latest example in a series of films in which Texas is nowhere.

In 1974 the first Texas movie appeared that had nothing to do with “Texas.” It was Benji, which was written, directed, and produced by Joe Camp of Dallas. After being turned down by every major film distributor, Camp distributed the film himself and wound up making more than $30 million in 1975 alone. Benji was the beginning of the native film industry in Texas. Twelve years later, despite Oscars for Tender Mercies, Places in the Heart, Terms of Endearment, and The Trip to Bountiful and despite hundreds of films made or set or financed in the state, Benji is still the benchmark of the Texas cinema in the Hollywood mind, where money is all that counts. The only other movie mentioned in the same breath is The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

The ironic development of the Third Coast is that it is the Texas filmmakers who have reduced the state to its neutral status. Where “Texas” once stood for large-scale life-and-death drama, the Texas seen through the native eye is almost perversely small. I don’t think there is another school of cinema outside of Czechoslovakia with such a bloated corpus of small arty films. It is odd to me that, in a culture that values money as much as Texas does, the movies it chooses to make are such fragile, intensely focused, personal stories as Raggedy Man, 1918, On Valentine’s Day, Blood Simple, and Last Night at the Alamo. They are the sort of movies that get enthusiastically reviewed by the New York Times but live most of their lives on videocassettes and in film-school seminars. They are playing, in other words, to highbrows.

The best of that genre, Tender Mercies and The Trip to Bountiful, both written by Horton Foote, showcased Oscar-winning performances by Robert Duvall and Geraldine Page. Foote himself received an Oscar for Tender Mercies and a nomination for The Trip to Bountiful. When I first saw Tender Mercies, a revolutionary artistic sensibility seemed to be at work—spare, controlled, uncompromised, utterly real. I also admired Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart, for which Sally Field won an Academy award. Yet the smallness of these stories leaves me gasping for air.

Nadine is another in this series of Texas miniatures, except that it isn’t even arty. As Nadine and Vernon plot how to get rich, outwit the cops, and cancel their impending divorce, they act out a story that, but for Texas accents, could just as easily have been set in Illinois. What is missing in these movies is scale, sweep, a sense of history moving underfoot. One has the feeling with Benton’s movies that growing up in Texas was a fond but incidental part of his personal history; he sees the state nostalgically. Good, important movies can be made in and about Texas—The Legend of Gregorio Cortez and True Stories are fine examples—but Texas filmmakers are so set on avoiding mythology that they have reduced themselves to a level that is smaller than life. As a Texan I appreciate the realism, the closely observed details of ordinary life, but as a moviegoer I find I’m longing for “Texas.”

Several years ago I was in Archer City, Larry McMurtry’s hometown, and I noticed a bulldozer razing a building on the town square. The building turned out to be the movie house—the same place that had inspired McMurtry’s novel The Last Picture Show and the movie that was made from it. I picked up one of the bricks from the rubble and thought about the wonderful scene in that movie, where Sonny and Duane and Billy, the retarded kid, are watching Red River. I remember feeling a powerful sense of identification with those boys who were living in Texas but whose imaginations at that moment were with John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in the greatest “Texas” movie ever made.

Larry McMurtry has written numerous screenplays, but his novels are what get made into movies. Hud, The Last Picture Show, and Terms of Endearment have, over the last three decades, marked the changes in Texas better than any other works. I thought about how McMurtry must have sat in that theater, feeling the ambivalence every Texan has felt when the myth looms over him. The Last Picture Show captured that ambivalence. Now is it ironic or simply inevitable that McMurtry’s greatest book, Lonesome Dove, would take place in “Texas”? He has reclaimed a legacy that all Texans share—that is, the legendary Texas of their imaginations. Maybe it is time Texas filmmakers returned to that territory with a native eye and made it our own.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Film