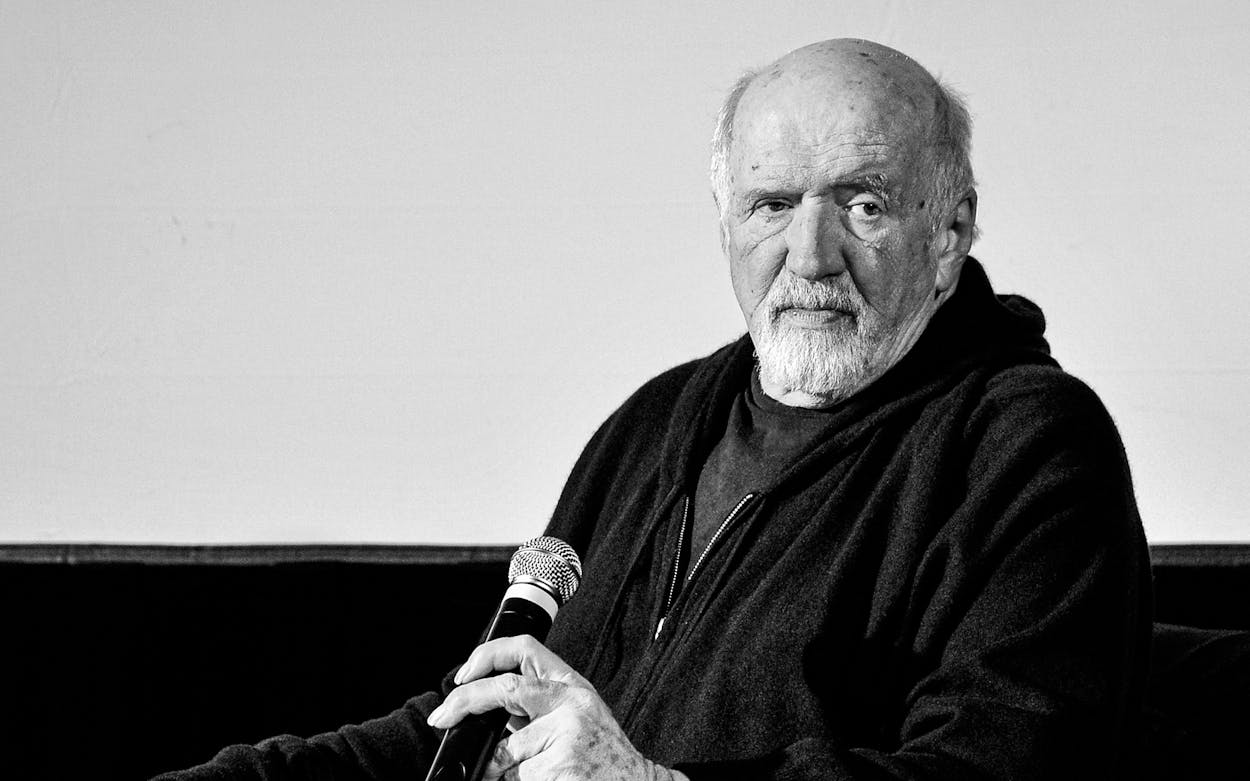

Maybe you already know that Dave Hickey was the seminal art critic of the past century. Before his death on November 12 at age 82, the Fort Worth–born writer collected most of the big prizes that the creative world can award: a Peabody Award, a MacArthur “genius grant,” and many, many other accolades “like that,” as Dave would have said about lists he trusted you could figure out on your own. Since I have zero knowledge of and even less interest in the art world, it never figured in our friendship.

This is about the Dave who was my friend. The off-duty Dave.

I met Dave 35 years ago at an Austin party hosted by a smart, glamorous group of women I thought of as the Art Babes. I wasn’t sure how I’d managed to slither in, but slither I had. I was barely in the door when a friend asked how the garage sale I’d hosted that day had gone.

“Well,” I told her, “the oddest thing happened. Not once, but two different times, little old ladies in giant Buicks drove up. Neither one got out. They just rolled down the window and yelled—”

“Milk glass?!” a tobacco-roughened voice imitating a twangy, exceedingly nasal North Texas accent interrupted, taking the words right out of my mouth.

My jaw dropped, since that was precisely what the ladies had asked for. I turned and there was Dave.

He had the imposing build and manner of a one-time linebacker whose knees had gone bad many, many seasons ago, crossed with the jaunty contrariness of a renegade leprechaun. There was about Dave an air of dukes-up Irish pugnacity leavened with an irresistible bad-boy charm; he was always almost as ready to joke as to jab. I was lucky. We started out joking and never stopped.

“Did they ask if you had any milk glass, jadeite, like that?”

“How the hell did you know that?” I said, asking the question that would define our relationship.

Instead of answering, he told me we were going out to the patio to smoke. There, after nonchalantly tossing off a thumbnail history of Depression-era hobnail glass pitchers, as well as jadeite (“like that”) and its recent rise in value, he said, “I liked that thing you wrote.”

In my second “How the hell did you know that?” moment with Dave, it turned out that he’d read the novel I’d recently published, Alamo House. That “thing” was a scene in the book. The scene, juvenile and dopey as it is, is worth describing because it reveals so much about the Dave who was my pal.

In it, my heartbroken heroine, forced by her cheating boyfriend’s betrayal to move into a dump of a housing co-op, contemplates “the half-dozen tenderhearted cockroaches that gathered at my feet like the kind mice that had altered Cinderella’s ball gown. The little guys waved their wee antennae at me in a touching display of interspecies commiseration.

“I hope they knew how much it cheered me to dispatch four of their number to Valhalla with my sandal. The two survivors scurried away to spread the tale of human perfidy (a tale that would cause my toothbrush to be peppered every night thereafter with tiny black roach turds).”

For a long time, I figured that Dave’s affection for this goofy passage was simply the master, the connoisseur, the arbiter of all that was hip and cool, taking a break to indulge in a bit of childish whimsy. As the years passed, however, I came to see that his affection for whimsy dwelt in the tender spot that he’d sheltered from the tragedies of his youth, including his father’s suicide when Dave was sixteen.

Over the next three decades, I watched Dave smoke innumerable Marlboro Light 100s on innumerable patios, balconies, and in a couple of hotel rooms where smoking was strictly forbidden. “Strictly forbidden” was the red cape Dave charged at his whole life. He had the superpower of making those he allowed into his secret clubhouse of naughty kids feel as if we, too, were rebels, transgressive and dangerous.

Then I went and did the least transgressive thing a woman can do: I had a baby. That, along with a nasty case of postpartum depression, would, I was certain, zero out any particle of cool cred I might ever have had, thereby canceling my membership in the Dave Club. Instead, though I never uttered a word about my particular brand of misery, Dave threw out a psychic lifeline: He took to calling me regularly simply to ask, “How’s my princess doing?”

And then he would talk about teaching at Harvard or his latest dust-up in the world of art criticism. He’d make me laugh and then ask how my work was going, as if I were still a functioning writer instead of an insomniac feeding station.

A bit later on, after I’d made contact with the child-care system, I moaned to Dave about how, not only had I failed to befriend a single other mom in the Mother’s Morning Out cabal, but, in spite of my concerted charm offensive, they actively avoided me. Why?

“The farmers always know who the pirates are, and they always hate them,” Dave growled, his voice further graveled by a few more years of Marlboros.

Whether or not this vision of me as a swashbuckling threat to staid bougie values was accurate or not (it wasn’t), it sure beat being the loneliest loser mom on the playground. Dave wasn’t always kind, but he was kind to me in ways that mattered a great deal.

Many years later, he published a book of essays with that exact title, Pirates and Farmers. From very early on, Dave and I bonded over titles. He liked hearing about the articles I wrote for women’s magazines on topics such as the infinity of ways the reader might intuit whether or not “he” was or was not “into” her. In this case, it was an essay I was writing for, yes, Cosmopolitan about my sad history of unwise clothing purchases and the sense of release it gave me to return said bad buys and start the cycle again.

“Binge Purge Shopping!” Dave decreed, bestowing upon this effort not just a title, but a whole guiding concept. I gave him 10 percent of what the cosmonauts paid me, writing “Title Tithe” on the memo line of the check I sent him.

Not all his ideas were bull’s-eyes, of course. Dave was convinced that my fifth novel, The Yokota Officers Club, really should have been called Yokohama Mama. His marketing scheme for the novel I set in the world of flamenco dance pivoted around the title “Cast a Net,” which, he promised, was guaranteed to “reel in” the fishing crowd.

He was also always eager for dispatches from my ten-year ramble through Hollywood as a screenwriter. When I once lamented that the producers on a certain project wanted me to both cut ten pages and “amp up” a minor character, Dave did not hesitate. “Cut out all his dialogue and have him playing a Game Boy and chewing on a toothpick,” he suggested. I did both, and the satisfied producers moved on. How the hell did he know that?

I think our phone calls, daily during certain periods, must’ve been a break for Dave. An opportunity to power down the hydraulic turbines that kept his big brain whirring. For a few moments, he’d put aside charting a new course for the art world or doing battle with the fussbudgets and puritans of any world and indulge in goofy puns and suburban chitchat.

When I learned that Dave would never call again, I relistened to one of the last voice messages he’d left me. Senate Bill 8 had just effectively outlawed abortion, and Dave railed, “Hey, Sarah, it’s Dave. I just wanted to talk to someone smart. What is going on? Texas is a vigilante state, you know what I mean?”

Anyone who ever spoke with Dave was asked, “You know what I mean?” multiple times during any conversation. Maybe even during a sentence. For Dave, so often the smartest person in any room, the question was a verbal tic he used to take the intellectual temperature and make sure that we were all following the mental gymkhana he was leading us through.

I like to think that Dave is now in his true element, where such a question won’t be necessary. And I hope that that element is the Allman Brothers Band touring bus, barreling down a 2 a.m. highway. The only lights are neon and everyone is smoking, ingesting the substances of their choosing, drinking caffeinated anything, and eating chicken-fried everything. And when Dave asks for the last time, “You know what I mean?” this crew will actually understand and the greatest riffathon ever will commence.

And they will treasure the Dave I knew, the off-duty Dave. The one who was that rarest of friends, the one who made you feel significantly snazzier than you actually were. The one who could always intuit when a bit of tenderness, a call simply to ask how his princess was doing, might be needed. The one who left you wondering, “How the hell did he know that?”

- More About:

- Art

- Fort Worth

- Austin