Shortly after David Gordon Green’s first feature film, George Washington, was released in 2000 to critical acclaim, he told me he was working a day job at a doorknob factory. The then-25-year-old had been crowned the “next Terrence Malick,” but he wasn’t sure if he’d have the good fortune to write and direct another movie. If he did, he said, it wouldn’t be another art-house film. “I’ve got three scripts that I’m trying to put the money together for right now that are very different from George Washington,” he’d explained. “One is a science-fiction film, one is a love story, and one is a comedy western.” He’d envisioned the latter as a major star vehicle that would cost thirty or forty million dollars, a far cry from his first movie, which portrayed the interior lives of children in an impoverished North Carolina town and cost $42,000. “I don’t want to classify myself as an art-film director or a big-budget studio director,” he told me. “I want to make movies I want to see.”

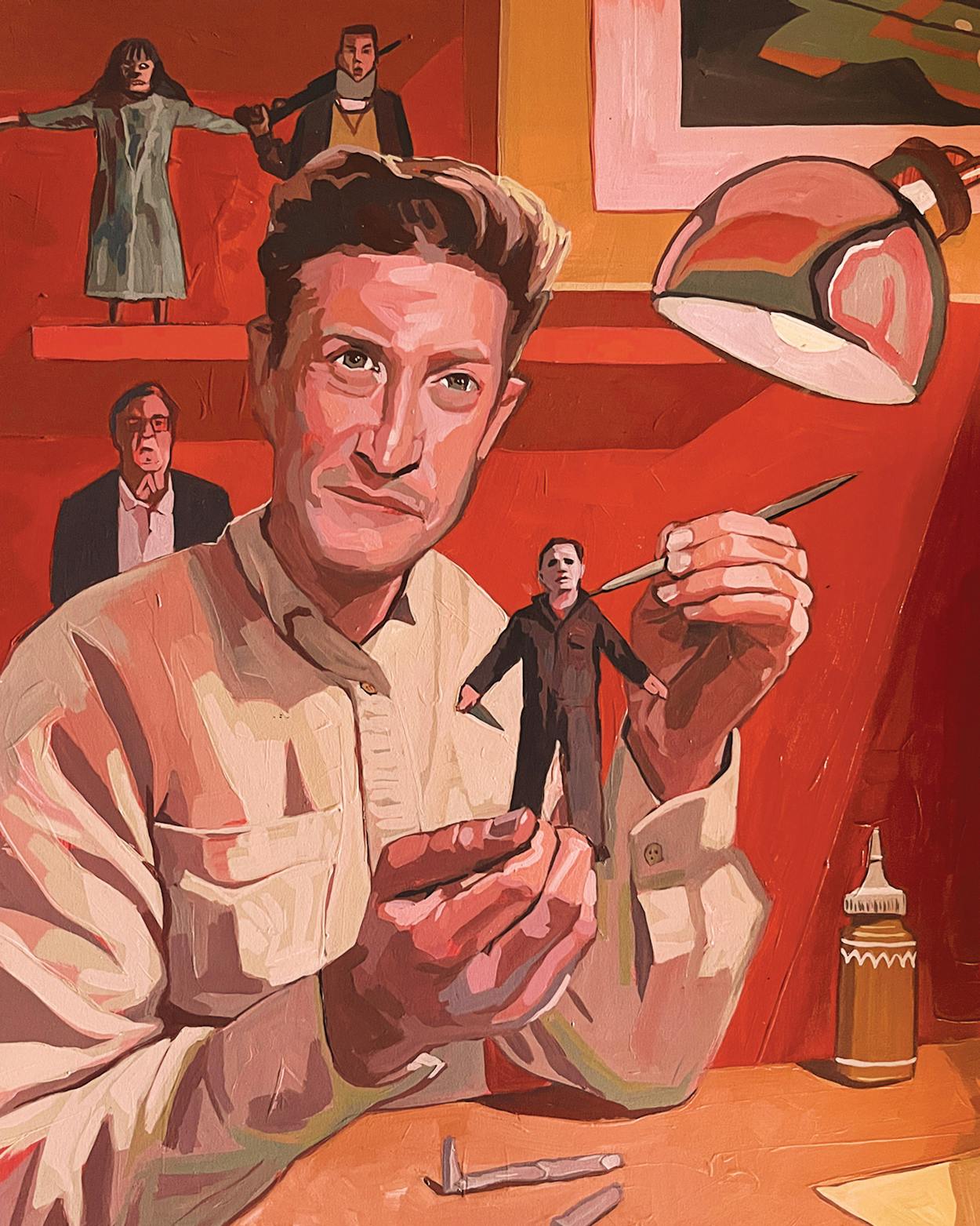

When I recently caught up with Green, I reminded him of our previous conversation and noted that he’d made good on his refusal to be pigeonholed (though we’re still waiting for the science-fiction film and the comedy western). Over the past two decades he has made indie dramas, stoner comedies, inspired-by-a-true-story films, and, most recently, a trilogy that reboots the Halloween horror film franchise. Speaking by phone from Savannah, Georgia, he explained that he had just finished an all-night shoot for Halloween Ends, which opens October 14 and is being billed as the conclusion of the long-running slasher saga. “You’re looking at your collaborators at two-thirty in the morning, and the sun is going to come up at five-thirty, and you’re like, ‘I’m not sure we’re going to make it,’ ” Green said. “And then we did. By the skin of our teeth.”

Directing a big-budget horror franchise wasn’t on anyone’s David Gordon Green bingo card back in 2000. But it’s completely in line with the expectations he laid out for himself. “I’m always looking to better myself or reinvent myself or try something new,” he said. Even if “something new” means crafting the most innovative way to stab a character in the face.

When Green was an adolescent growing up in Richardson, just north of Dallas, movies were his thing. “There were an electric, eye-opening few years, from when I was eleven years old to fifteen years old, probably the time of my life when I was the most alone,” he said. But Green said it was also a period of feeling some emotions for the first time. He’d watch flicks such as the dark romantic comedy Harold and Maude and come away looking at the world in a different way. “If you could just bottle that newness, the first time, the virginity of your life,” he said. “That anticipation for what else is out there and what that forbidden fruit is, that’s kind of what I’ve been trying to re-create.”

In 1988, when he was in eighth grade, he got to witness filmmaking firsthand, when he was hired as an extra for a scene in Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July that was shot in Dallas. (Green looks into the camera and wiggles his eyebrows during a baseball game.) He observed how Stone conducted the proceedings and communicated with the actors and crew.

Maybe, he thought, he could become a director. Green didn’t come from money—he worked at a cinema as a teenager to sustain his movie-

watching obsession—and didn’t know anyone in show business, but he was studying films the way many of his peers were analyzing football games. By the time he graduated from Richardson High School, he was screwing around with a rented 16mm camera, and after a brief stint at the University of Texas at Austin, he went to University of North Carolina School of the Arts, where he met a few other film students—Danny McBride, Jeff Fradley, and Jody Hill—who would become his frequent collaborators.

Early on, he knew that he wouldn’t be a director with a trademark style or genre focus. He felt more akin to Richard Linklater, who directed the $23,000 Slacker and the $35 million School of Rock, and Werner Herzog, who made the big-budget epic Fitzcarraldo and the lower-budget documentary Grizzly Man. “They were always messing around with stuff,” he explained. “You don’t feel like they’re scientists of brilliance and precision. You feel like they’re adventurers on a journey.”

After George Washington, to pay the bills, he shot commercials, couch-surfed, wrote scripts, and worked in the doorknob factory. The factory paid well, he told me in 2000, because of the high exposure to toxic chemicals. He would dunk flawed, bronze doorknobs in acid until the bronze came off. “I have gloves and a nice moon suit I slip on to be stylish,” he said. “It’s not half as much fun as it sounds. It keeps my humility, and it’s nice because I meet a bunch of strange people there that I have thoughts about and write about. I mean, the last thing I ever want to do is make a movie about making a movie. Anybody who writes a script about a struggling screenwriter needs something to do. Take a vacation.”

Despite his ambition to work in a variety of genres, the three films Green made after George Washington were also small-scale art-house dramas (All the Real Girls, Undertow, and Snow Angels) that critics adored. Green had earned a reputation as a filmmaker who, in the lavish words of Roger Ebert, had a “gift for moments of acute observation, for dialogue both naturalistic and uninflected, for mood over plot, for poetry over prose.”

They should brace themselves. Green describes Halloween Ends as a coming-of-age love story. “Nobody has any idea what this movie is about,” he said of the public. “It hasn’t leaked!”

Green took that reputation and chucked it. His 2008 stoner-buddy movie Pineapple Express, which starred James Franco, Seth Rogen, and Green’s old film school buddy McBride, was generally well-received; his next two attempts at comedy, both released in 2011, were duds: The Sitter, starring Jonah Hill (“Not Superbad, just quite bad,” in the words of one critic), and Your Highness, a mirthless romp set in medieval times. “What calamity has befallen [Green]?” a crestfallen Ebert wrote. “He carried my hopes.” Two years later, the film’s costar, James Franco, told GQ, “That movie sucks.”

He regained his critical stature with two Texas films: the Bastrop-shot dramedy Prince Avalanche, and Joe, a dark Southern Gothic drama filmed in the rural woodlands of Central Texas. Not long after, the horror production company Blumhouse asked Green if he wanted to try something completely new: rebooting Halloween.

Halloween fans were excited that a serious talent had agreed to take on the franchise, which had fallen on hard times after four decades of mostly dismal attempts at reboots and sequels. The 1982 effort Halloween III, directed by Tommy Lee Wallace, somehow worked Stonehenge into the story line; 2009’s Halloween II, the second installment of an ill-considered reboot written and directed by heavy metal musician Rob Zombie, featured a cameo from “Weird Al” Yankovic. Green had never made a horror movie and was excited by the challenge, which he approached with a combination of studiousness and deference. He and McBride ran their script past John Carpenter, the creator of the first Halloween film, and Green regularly consulted Carpenter on directorial decisions. “I’m dealing with characters I certainly didn’t invent,” Green told me. “But I’m able to continue these mythologies in a lot of ways, and people take them very seriously.”

In making his Halloween movie, Green used styles of editing, sound design, and directing that were geared toward building heightened suspense and making each “kill” feel novel, as if each had a personality of its own. The hard work paid off. Halloween, which was released in 2018, bears the stylistic hallmarks that made the original 1978 film, of the same title, timeless. Critics and fans loved it.

Green’s second and third films, though, have strayed from that template. 2021’s Halloween Kills was more like a gory action movie, a significant departure from Carpenter’s original, which, famously, shows very little blood. Critics and fans, who were expecting something more in line with the 2018 movie, were lukewarm. But they should brace themselves. Green describes Halloween Ends as a coming-of-age love story. “Nobody has any idea what this movie is about,” he said of the public. “It hasn’t leaked! And it’s a fun time to be like, ‘Yeah, we’re doing something no one sees coming.’ It’s just funny to have that power on my laptop.” Once the movie comes out, Green will be done with the Halloween franchise, while continuing a streak of horror films: he’s developing a reboot of The Exorcist (again, as a trilogy) and an HBO series based on Clive Barker’s Hellraiser story.

Not that Green is settling into a genre. A few days after we spoke, he started shooting season three of the HBO comedy series Righteous Gemstones, starring John Goodman and McBride. He’s also developing a movie about Walt Disney. He mentioned possibly collaborating on an animated series inspired by a nineties video game. “Maybe it’s a short attention span, but to me, it’s just curiosity and excitement about an industry that is kind of limitless,” he said. “So why not play with the boundaries a little bit and see what you can get away with?”

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Jack-O’-All Trades.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Movies

- Filmmaker

- Richardson