“You just would not have believed it: first, he quits The University of Texas right before his senior year to turn pro. I mean, people have been telling him that he’s losing a hundred grand a year by staying in college, so why not, right? He goes to the PGA’s 144-hole qualifying tournament last fall, and he drowns everybody, wins the damn thing by twelve shots. But then he enters his very first tournament as a card-carrying pro, the Texas Open, and he wins that, too. I mean, it’s just unreal!”

Fat Cat stretched his more than ample frame across the cushy bar of a prestigious Houston-area country club, and waved in the general direction of the 18th green. We were waiting to meet Ben Crenshaw, the rookie touring pro from Austin whose golfing skills have made him one of the richest young college drop-outs in America. Both Fat Cat and I had played golf with Crenshaw back in the late Sixties when we were all teenage golfers on the Texas amateur junior circuit. But since that time I had made the rather dubious decision to give up golf for journalism, and I hadn’t really kept up with Crenshaw’s career. Fat Cat, on the other hand, had followed our old friend closely—in mind and spirit, if not in golfing success—and he insisted on reviewing Crenshaw’s entire life history, stroke by stroke, while we waited for Ben to arrive.

Fat Cat loves the story about Crenshaw winning his first tournament. Ben was leading Lee Trevino by a stroke coming up to the 18th hole, and all he did under pressure was knock home a birdie putt to win by two strokes. But Fat Cat doesn’t spend much time talking about Crenshaw’s golf game. “Every day, about 30 or 40 of these starry-eyed coeds from Trinity University are out at the course wearing ‘Ben’s Bunnies’ T-shirts that don’t exactly leave too much to your imagination, and they yell and scream for him as if he’s some kind of candy-coated chunk of unadulterated sex appeal. Meanwhile, he pockets a cool 25 grand, and becomes an overnight media idol.

“The next thing you know, his blond, blue-eyed all-American mug is on the cover of Sports Illustrated and just about every single golf magazine that ever found its way into a pro shop. People want him to do commercials hyping everything from liquor to ladies’ lingerie. Tournament sponsors, tour groupies, other touring pros—everybody just gushes and drools over him and his game. He has the physical stamina of Gary Player. The mental attitude of Jack Nicklaus. The charisma of Arnold Palmer. And not only that, in the middle of Watergate America, the kid is even honest to a fault. There was that time he accidentally kicked his ball in the National Junior Amateur qualifier at Houston Country Club. No one saw his ball move but him; he could’ve kept his mouth shut, qualified for the tournament, and won the whole damn thing. But oh, no, that’s just not Ben Crenshaw. He calls a one stroke penalty on himself, and misses qualifying by just that. He loses a chance at the National Junior, but wins everybody’s heart instead. He’s a super-straight, 22-year-old super-duper-star. He’s golf’s Big Three all rolled into one stocky blond bundle of modest charm. You know, it’s almost enough to make you sick. But I guess it’s to be expected—I mean, the man really is one helluva player.

“So anyway, our man becomes ‘Gentle Ben’ and is followed by ‘Ben’s Bunnies’ and ‘Ben’s Wrens’ and ‘Crenshaw’s Cuties’ and every other kind of ad hoc women’s worship group that can figure out a title from the guy’s name,” Fat Cat continued. “But then, he fails to win the Masters or the British Open or the U.S. Open or any other tournament. All of a sudden, the press, which believed that he would win the Grand Slam in his rookie season, starts to get on his back. They keep asking him, ‘What’s wrong? What’s the matter with you?’ And what can he tell them? ‘I’ve been playing bad. I’ve been in a slump’.”

Fat Cat shook his head sadly and let out an envious moan. “Any weekend golfer and at least half the pros on the tour would give away their last set of clubs to experience what Ben Crenshaw calls a slump. Besides his first-place finish in the Texas Open, he gets three seconds—the World Open, the Dean Martin-Tucson Open, and the New Orleans Open—and in the first nine months of 1974 he wins more than $66,000. That puts him in the top thirty on the official PGA [Professional Golfers’ Association] money-winning list. Sure, he misses the cut in a few tournaments. But so what? Only a handful of players even get by the PGA tour-qualifying tournament each year, and over half the tour rookies never make it back for their second season. Crenshaw says he is having a bad year, and he wins more than 90 per cent of the pros, even beats out big names like Frank Beard, Gay Brewer, and A1 Geiberger.

“But for some people, I guess that’s just not good enough: Crenshaw is expected to win—everything. And pretty soon, the kid himself starts to believe that, lets it prey on his mind. I mean, you’d think he was kind of half-psycho anyway, always talking about ‘going into a trance when I get on those old courses in the East,’ half-pretending that he’s battling Harry Vardon for the U.S. Open of ought-something-or-other. So this bit about winning really starts to bother him. On the outside, he’s all confidence. He tells me he thinks he’s capable of winning any tournament, that he proved that in San Antonio. But you just know that all the publicity pressure is on his mind, and that every time he tees it up, he’s telling himself, ‘Now, just don’t do anything stupid, just don’t take the gas and look like a fool.’ So, of course, he blows a few tournament leads—like in the Canadian Open when he dumped a shot into the water hazard on the 16th hole—and he becomes so preoccupied with winning that it’s a minor miracle he can still draw the club back.”

We reminisced for a while about our own golfing careers and what it was like to play against the fifteen-year-old kid who people were already saying would be the best golfer to come out of Texas since Ben Hogan. Texas was filled with good young golfers in the late Sixties, players like John Mahaffey, Tom Jenkins, and Tom Kite, all of whom are on the tour now. Kids were winning the sixteen-and seventeen-year age brackets of the state junior tournaments with scores below par, and even the fourteen- and fifteen-year-olds were fighting it out at just a few shots over par. But of all the hotshot young players, Crenshaw was the best. He shot a 74 when he was only eleven, and saw his picture in the Austin newspaper for the first time. By the time he was fourteen, he shot in the low seventies consistently and occasionally would dip into the sixties. (“That’s from the back tees,” Fat Cat emphasized.) He won the state junior title at fifteen, shooting rounds of two and three under par, and I can still see him standing over the ball crouched in picture perfect position—shoulders slightly hunched, arms pinched in at the ribs, his hands wrapped around the club in an overlapping grip, his feet spread wide. (“You just knew he was going to kill it,” Fat Cat said, “even if he was only 5’9” and 165 pounds, and isn’t much bigger than that today.”) Slowly, smoothly, he’d draw the club back just past horizontal, over-swinging just a fraction and swaying almost imperceptibly as he shifted his weight to his back leg. He’d pause for an instant, just long enough for you to see exactly what a backswing should be, then whip the club through in a powerful inside-out path: whhhkhhaaack! He made it look so easy.

Fat Cat took up the story again: “The amazing thing is that unlike almost any other low-scoring golfer in the world, the kid could count the number of golf lessons he has taken on the fingers of one hand. He is just a natural athlete. They say he would have made a pretty fair pitcher on the baseball team and not a bad guard on the basketball team at Austin High School if he hadn’t given up all his other sports for golf. Instead of having to shell out hundreds of bucks to some teaching pro, he learned to play the game by riding around in a golf cart with his father. Old Harvey Penick at Austin Country Club, who’s one of the few really good teachers in the whole country, showed Ben the grip—or as Ben always puts it, ‘something about the grip.’ From there, it was all Ben’s instinctive feel for the game.

“After winning every conceivable Texas junior tournament, he goes on to the University of Texas, where he wins three straight NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association] individual championships, something no one else has ever done. He also wins just about every amateur title imaginable, including the Porter Cup, the Eastern, the Western, and the Trans-Mississippi. In fact, his last year as an amateur he wins eleven of the fifteen tournaments he enters. The only amateur championship he never gets to win is the U.S. Amateur. He finishes second in 1972, but has to pass up the tournament in 1973 because of his decision to turn pro that summer. It’s too bad he misses out on winning the biggest amateur tournament of them all, but as he himself says, ‘I belong on the tour.’

“Which brings us back to where we started—all that ‘Gentle Ben’ and ‘Ben’s Wrens’ stuff. Now, I can appreciate the necessity of a good cliché every once in awhile, and I know how you writers like to get hold of a stock story and just hammer it out and go to bed. But I am sick and tired of hearing about ‘blond, blue-eyed Ben Crenshaw, the flaxenhaired boy hero with his bevy of beautiful girls.’ I mean, sure, the guy’s handsome, and there are always plenty of chicks hanging around the major tournaments, and a lot of them would probably lie face-down in a sand trap all day if that’s what it took to go out with him. But he’s not man’s last word to woman. And he’s not just Peter Purity, the all-American Simple-Dimple, either. Sure, he’s real polite and kind of quiet and all the little old ladies who keep score at the tournaments’ just love him to death. But if you’re going to write an article about the guy, you should at least mention that he smokes cigarettes and drinks liquor and likes to raise hell every now and then, and that he’s even been known to tell an off-color joke. He’s got one great story that he picked up when he played an exhibition match with Sam Snead up in Toledo. Snead goes on safari in Africa, see, and he sneaks up on this water buffalo and just blasts it. Then he starts thinking about how some of the water buffalo’s carnal organs might make a pretty good shag bag. So Snead cuts off the water buffalo’s head, then he cuts off the water buffalo’s…”

All of a sudden Fat Cat’s monologue was interrupted by a thick Texas drawl: “Don’t you believe a word he’s saying. If it comes from Fat Cat, it can’t be true.”

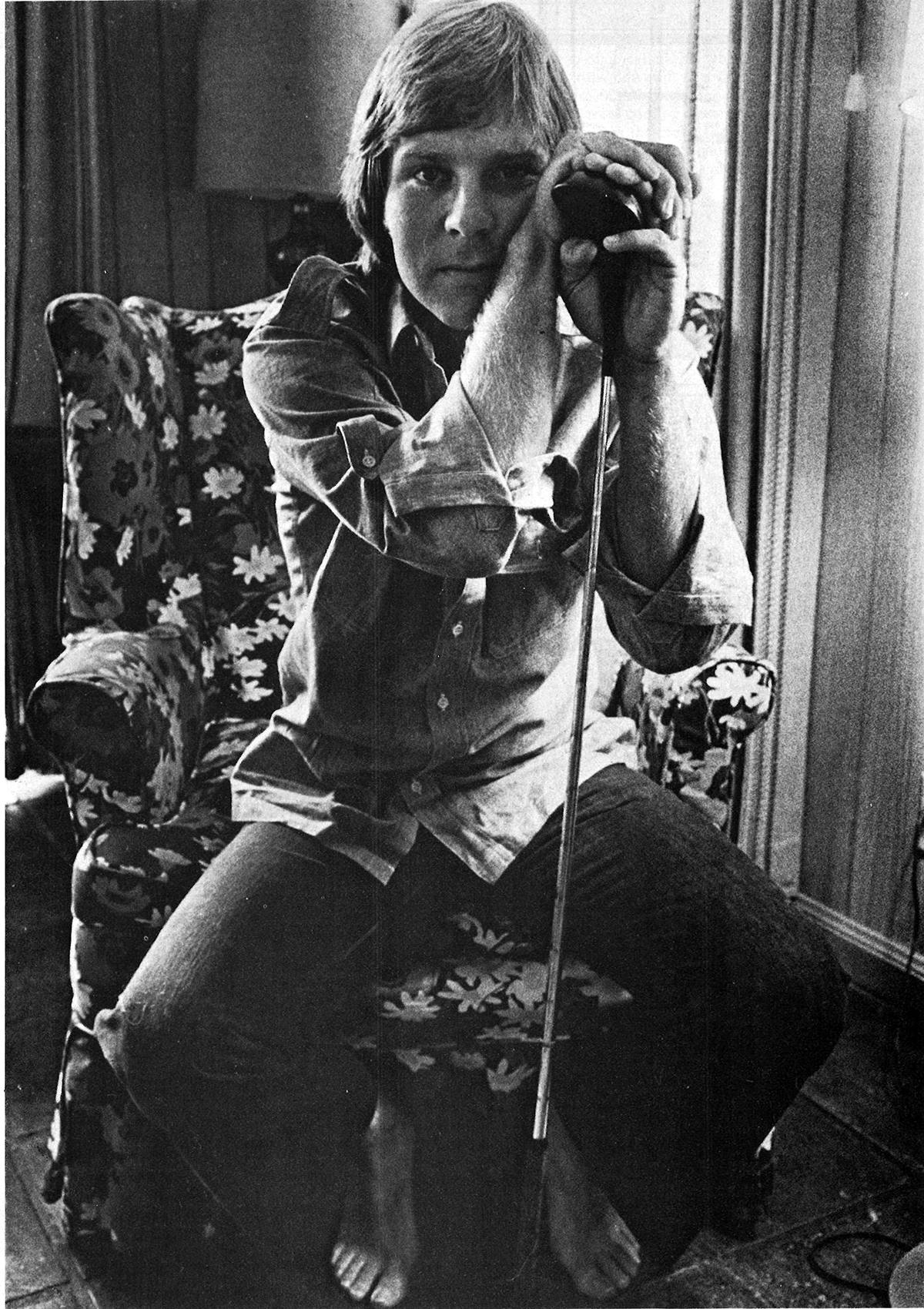

It was Crenshaw—at last. He was wearing a pair of powder-blue beltless slacks and a white shirt covered with red and blue quadrilateral designs. He looked almost exactly the same as he had when I last saw him, back in the summer of ’69, except that now his sideburns were a little more pointed, and his hair was a little longer, gently grazing the very top of his collar. He probably would have been called a hippie if he had looked like that five years ago, but, having kept pace with the national style, he was simply “modish,” just a few clips away from clean cut. After good-naturedly roasting Fat Cat for a bit, he lit up a cigarette and began to give his version of The Ben Crenshaw Story, which, to my amazement, coincided with Fat Cat’s account in every significant detail. Of course, Crenshaw did have a few things to add:

“This first year was just a learning process,” he said, sipping a beer. “I really don’t know which tournaments to go to and which to skip next year. I know a few I won’t play in—like the Bob Hope Desert Classic. Palm Springs is just… well, you can have that place, it was bad. The people there are just a bunch of people from New York and Los Angeles, and they don’t care if you’re there or not. When you feel like you’re not welcome, you just can’t play up to your best abilities. I was talking to Jack [Nicklaus] about it, and he said, ‘Just don’t go to the Bob Hope. You don’t need that kind of tournament’.” “Oh, so you were talking to Jack, huh?” Fat Cat intruded. “I suppose you mean Jack Nicklaus, golfs so-called ‘Golden Bear,’ and I suppose he’s taken you right into his financial lair because you’re golf’s ‘Golden Cub’ now or something like that.”

“Jack’s been very influential on what I’m doing in business right now, but he doesn’t have any financial interest in me,” Crenshaw responded evenly. “We’re good friends, and we talk a lot, and he suggests things that he knows about from his experience. Boy, he’s such a mature person, and he really knows a lot. He’s become a great businessman, and right now he’s well on his way to becoming a very rich man. But three or four years ago, he was just in pitiful financial shape. He started off on the wrong foot when he started with [Mark H.] McCormack [who manages Arnold Palmer and other sports stars]. Then he got a group of four advisors who bailed him out. Now they’re advising me. One of them lives in Austin. His name is Bill Sampson, and he’s a marketing and advertising man. He handles most of my business deals, and I have a secretary who takes care of my travel arrangements. That’s my whole set-up. I’m not being managed by anybody. I just didn’t want to get into a managerial situation because I just didn’t think it was right to give up twenty per cent of what you make away from the golf course and twenty per cent of your tournament winnings. I could see a manager taking fifteen or twenty per cent of what he makes for you off the golf course, but I just couldn’t see him taking prize money. I just pay my advisors a flat fee like any client would pay a lawyer. I had borrowed the money to play amateur golf and start out on the tour, and I used to hate to have to cut up my winnings and give them to some guy in a bank back in Texas.

“The set-up I have now is working pretty well, too,” Crenshaw added. “Last year, my tournament winnings were close to 75 per cent of my total income. I did a few things on Mondays—little pro-ams and stuff—that amounted to about fifteen thousand. But this year, I’ll probably get 65 or 70 per cent of my total income from non-tournament stuff. Still, I haven’t signed with a club manufacturing company, and I haven’t affiliated with a golf course or a country club or any kind of complex like that. I’ve been doing a bunch of exhibitions for the Heublein Corporation, the people who make Black and White scotch. That’s going to amount to a pretty good chunk. I guess in pro-ams and little Monday exhibitions, I’ve made about a hundred and twenty thousand this year. Before the end of ’73, I made all this money at once, and I had to pay so much back to the government it was unreal—like about 40 per cent of it. But now we’re getting into a few investments. The tax lawyer I’ve got is a guy named Jerry Halperin in Detroit. He handles people like Henry Ford and Jack [Nicklaus]. He’s an ultra-conservative guy, and he’s just not one to get into speculative types of things.

“But actually, I’d like to stay Texas-oriented, and work from there. Start out slowly—maybe build a couple of duplexes, things like that. Get a feeling of it, then speculate a little more. Some day, I’d like to get into golf-course architecture, too. I’ve talked to all the major architects—Trent Jones, George Fazio, Joe Lee, Dick Wilson—and it seems to me that people want to make money off golf courses, but that they’re just not doing a good enough job on the courses themselves. I figure if you get a good piece of property, and you make a golf course that’s good for the members and pretty tough for the professionals, there’s no reason why you can’t sell lots and real estate, too. So many ventures today just start selling lots. The layout’s too crowded and the golf courses just aren’t as good.”

“O.K., so you’re a big businessman now, ‘Gentle Ben’,” Fat Cat said mockingly. “But what about all the prejudices in golf? I mean, it’s probably more discriminatory than any other professional sport. If you’re such a rich young hotshot, what are you going to do about that? Does it even bother you?”

“It certainly does,” Crenshaw replied, apparently unflustered by Fat Cat’s rudeness. “I guess by and large, the black players out on the tour and the black caddies get along with the white players, but that’s where it stops. The black pros don’t feel like they’re welcome any place. And they’re the nicest guys you’d want to meet: they don’t go out and raise hell; they’re just out there trying to make a living like everybody else, and I really respect them for it because it’s damn hard. One guy who feels awfully bitter about it is Charlie Sifford [the first black to come on the tour], but he can’t do much about it now because he’s getting old and he can’t play as well as some of the younger blacks. You know, a story came out the other day saying that he couldn’t even get a club pro job—isn’t that incredible? I guess golf is just going to be a white man’s game for a long time. There are just so many things about it that you’d have to change, and it’s so hard for a young black player to get the money to go on tour. I’ve thought that some day I might just come out and say that something ought to be done. I wouldn’t know how to go about it, but I’d be sympathetic.”

That answer shut Fat Cat up long enough for me to ask what ambitions Crenshaw had, what three dreams he most wanted to come true. His answers were far less elaborate than some of the answers he gave to Fat Cat’s irritating inquiries. His first dream (surprise) was to become “the greatest golfer that ever lived.” His second dream was to make a comfortable living; at age 22, that one was already pretty much accomplished. But Crenshaw’s third dream… well, that one was hardly as predictable as the other two. Indeed, it nearly brought the hulking Fat Cat out of his seat.

“I think I’d like to find a wife,” Crenshaw said, then added quickly, “Not that I’m going to get married any time real soon, but you really do need a good wife you can come home and talk to when you’re out on the tour.”

“Whaaaaaaat?” Fat Cat bellowed. “You can’t do that. What about ‘Ben’s Bunnies’ and ‘Ben’s Wrens’ and all those girls who’d lie face-down in a sand trap all day just so they could go out with you?”

“Aw, Fat Cat, you know that’s just a bunch of crap,” Crenshaw replied softly, and blushed. “Besides, I said it wasn’t going to be any time real soon.”

And with that, Crenshaw got up to leave. He had to be off to Toledo or someplace like that the next day, and he didn’t have any more time to fool around with the likes of Fat Cat and me, though he would never have put it quite that way. He plunked down a rather sizeable bill to cover our rather sizeable bar check, and said good-bye.

“Like I was telling you, the man’s one helluva player,” Fat Cat said, guzzling a triple scotch as he watched Crenshaw leave the room. “He’s just one helluva player.”