Don Hertzfeldt meets me at a restaurant in his North Austin neighborhood. This, in itself, is notable. One of the most celebrated animators of our time has been living here in Texas for nearly nine years now. From 2000’s cult hit Rejected to 2015’s Oscar-nominated World Of Tomorrow, he’s collected awards and critical accolades, along with the kind of rabid fans who turn his oddball creations—wobbly stick figures, goggle-eyed bananas, adorable fluffballs spraying blood—into tattoos and Twitter avatars. But chances are you’ve never run into him. He doesn’t get out much to bask in the adulation.

Hertzfeldt doesn’t own a smartphone, and sees no reason why he should. After all, he rarely leaves his house. When he arrives for our interview, he pings me from an iPad, using an ancient Hotmail address. At one point during our two-hour conversation, he says he finds getting together with anyone, even his closest friends, physically exhausting. He likens most people to “energy vampires” who drain him of all his creative force. On any given night, he says, he’d much rather be home in his studio.

My reason for disturbing him is because Hertzfeldt’s first (and to date, only) book, The End Of The World, is being reissued this month by Random House. The original edition, an independently pressed run of just 5,000 copies, sold out almost immediately back in 2013; today these fetch hundreds of dollars on eBay. Despite Hertzfeldt’s protests that he’s not an author—even though Random House has already commissioned him to deliver another book—he suddenly has to act like one, and go through the press junket rigamarole to promote it.

He couldn’t be nicer about all this, by the way. Hertzfeldt smiles easily and talks thoughtfully, his lank hair and slightly neurotic surfer’s vibe betraying his origins in the San Francisco Bay Area, even as his Western shirt screams Austin. Nevertheless, I feel like a bit of a jackass. While we sit here, I am constantly aware that I’m actively delaying at least two Don Hertzfeldt projects.

One of these will remain a mystery for now (Hertzfeldt refers to it repeatedly as “this thing”). The other is the third episode of World of Tomorrow, another follow-up to the acclaimed, Academy Award-nominated short that, despite its brief 22-minute running time, was singled out by many critics as one of the best movies of 2015.

World of Tomorrow tells the story of a girl named Emily (voiced, in spontaneously recorded dialogue, by Hertzfeldt’s four-year-old niece) who’s visited by her adult clone from a dystopian future, who fills her on civilization’s incipient collapse. It’s a loopy sci-fi premise that, in both the original and its 2017 sequel, World of Tomorrow Episode Two: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts, Hertzfeldt transforms into a deadpan, devastating comedy abouthe precariousness of existence and memory. Using little more than two-dimensional stick figures chattering at each other over shifting blobs of color, Hertzfeldt creates depth and pathos that puts most flesh-and-blood films to shame.

In addition to completing World of Tomorrow Episode Three, Hertzfeldt is also currently shopping World of Tomorrow as a limited series, saying the story could eventually expand into as many as seven or ten episodes, if and when he finds a willing home. This would finally free him from having to always figure out distribution. He’d also love to get a little seed money to open up a small production studio in Austin, and maybe find some other animators and at last hire some help. In the meantime, Hertzfeldt is working the way he always has: one frame at a time, alone.

It’s been like this since Hertzfeldt first attended film school in the 1990s. Raised in Fremont, California, by an airline pilot father and a library clerk mother, he arrived at the University of California, Santa Barbara with aspirations of becoming the next Steven Spielberg. Unlike some of his classmates, Hertzfeldt couldn’t afford to splurge on the 16mm film stock that students needed to complete their live-action projects. By then he’d already toyed with making cartoons in high school—crude stop-motion things he’d rendered on VHS—and he soon figured out he could fit an animated short onto just two rolls of film, without worrying about wasted takes. Animation also allowed him to work late at night, on equipment hardly anyone else was using—a process that would soon define his career. It taught him a formative lesson about its powers. “You might spend $30,000 on your student film, but you’ve still got your roommate playing a 30-year-old detective,” he says. “Animation, you’re only limited by what you can draw.”

Hertzfeldt never actually studied animation. His earliest student films, 1995’s Ah, L’Amour and 1996’s Genre, are more like parodies of the form, mockingly aware of their own conventions and pretensions. In both movies, Hertzfeldt seems self-conscious about anyone taking him as a “serious” animator. To this day, he still regards himself as a far better writer, editor, and even sound designer.

He’s more comfortable talking about his animation heroes—like Bill Plympton, the indie animation guru whose bizarre shorts found their niche at film festivals and cable TV, carving the narrow path that Hertzfeldt’s own work would follow. He waxes reverently of old-guard Disney guys like Who Framed Roger Rabbit? animator Richard Williams, admiring his masterful command of movement. Still, Hertzfeldt has always drawn more inspiration from newspaper comics, particularly people like Peanuts creator Charles Schulz, whom Hertzfeldt hails as one of the great artists of the 20th century.

“I think what a good cartoonist does is you strip things away, and you only leave what’s important,” he says of Schulz’s work and, by proxy, his own. Schulz created indelible characters using just a few circles and dots, and Hertzfeldt’s work lives within similarly minimalist panels, using simplistic figures to provoke empathy. His final student film, 1998’s Billy’s Balloon, finds one of Hertzfeldt’s own little round-headed children being mercilessly attacked by his red balloon. Like a sadistic twist on Charlie Brown’s kite, it evokes Schulz’s recurrent themes of adorable kids grappling with a cruel world.

Billy’s Balloon competed at the Cannes Film Festival, won the Grand Jury Prize at Slamdance in 1999, and had critics hailing Hertzfeldt as both “hilarious” and “a psychopath.” The money he earned by selling it, along with his other student films, to MTV and European television helped him purchase the 1940s-era 35mm camera that, coincidentally, was used to shoot many of the original Peanuts cartoons. Hertzfeldt immediately used this 10-foot “mechanical cow” to make Rejected, a self-conscious satire about an artist surrendering to crass commercialism.

Rejected consists of a series of bizarro, blood-spewing interstitials for an imaginary cable channel, alongside fake ads for things like Bean Lard Mulch—an anti-capitalist satire that eventually implodes into full-bore existential terror. It was nominated for an Oscar in 2000. More importantly, it became a pre-viral sensation, thanks to its theatrical run as part of Spike and Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation and subsequent bootlegs. Today, Rejected is often cited as a strong influence on the kind of surreal, self-aware humor that Adult Swim later made the lingua franca of the internet.

The success of Billy’s Balloon and Rejected, Hertzfeldt says, also led to him becoming stuck inside his own limited confines in Santa Barbara. As most of his college friends moved away, Hertzfeldt remained chained to his immovable camera, often going weeks without talking to anyone while going from one project to the next.

“It felt like an old Twilight Zone episode where you make a deal with the devil—like, ‘You’re gonna be able to do whatever you want to do, make any movie you want, and there’s a little audience for it, but I’m gonna take away this and this and this, and you can never leave,” he says. “Christmas would come around, and I would be like, ‘I can’t believe it’s Christmas again.’”

One of the other byproducts of that solitary confinement was writing The End Of The World, which he describes as “the strangest creative exercise I’ve ever been involved with.” Back in 2005, a friend of his was assembling a graphic novel anthology and asked Hertzfeldt to contribute. Knowing nothing about how to structure a comic book, he realized he could fit six Post-It notes to an 8.5 x 11” page and use them as yellow panels on which he drew a series of tiny, bizarre scenes he pulled from stray thoughts and nightmares. Even after he submitted that initial batch, and his anthology was published, Hertzfeldt found he couldn’t stop making them.

“You know how in the Olympics, you see these swimmers in their races, and they have a cool-down pool they soak in before they get out of the water?” Hertzfeldt says. “The book felt like that to me. I’d animate and animate all night, and then I’d have these extra ideas and things that didn’t quite fit, and then it would trickle down to these weird little Post-It drawings. I’d do one of them, then maybe nothing for two years. It was the ocean floor where everything collects.”

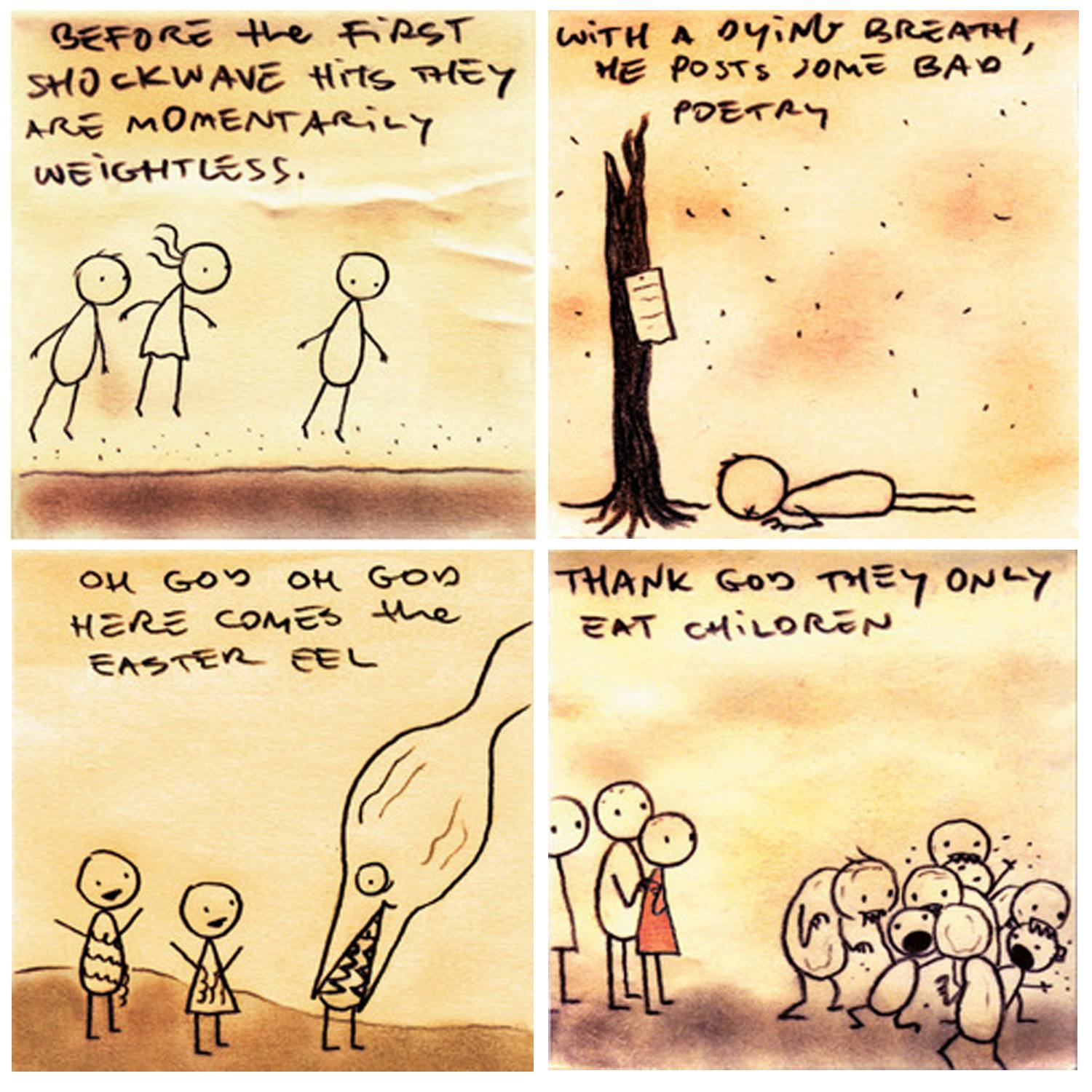

In 2013, Hertzfeldt’s friend Gabriel Levinson suggested he do something for his independent publishing company, Antibookclub. Hertzfeldt went back to that stack of Post-Its and began rearranging. He found that panels he’d drawn six years apart took on new meanings when they were juxtaposed, forming a vague narrative—albeit one Hertzfeldt deems “completely inscrutable”—about humans living through the wake of apocalypse. Across a series of single-panel gags, each page consisting of one enlarged Post-It note (often with stains and tears intact), we watch as everything crumbles: Crustaceans commit mass suicide. Survivors follow mysteriously-faxed coordinates toward possible sanctuary, as they write bad poetry and slowly go insane. In one particularly memorable scene, children drape themselves in kelp in hopes of being eaten by the Easter eel.

Like all of his work, this silliness crashes into moments of heart-stilling sorrow, all of it cut with a uniquely mordant streak.

Hertzfeldt is, if not completely dismissive of The End of the World, then at least suspicious. He finds it a little baffling that a major publisher wants to put it in Walmarts that don’t even stock his movies. He’s unsure how even his diehard fans will react to something he has described, with varying degrees of affection, as both an “art object” and a “parody of a book.”

The reissue restores a few scenes that were cut from the original edition (for reasons he can no longer recall), and these add a bit more depth to the insanity. Still, Hertzfeldt likens The End Of The World variously to a collection of B-sides, to refrigerator magnet poetry, and even (quoting one “very generous” friend) to jazz. It’s the most unconscious thing he’s ever done, he says, born less of inspiration than of compulsion.

Those tendencies haven’t changed much since he moved to Austin in 2010. Hertzfeldt came to Texas because of the lower cost of living and relatively laid-back pace, to be closer to friends and have some semblance of a social life, and to be part of the Alamo Drafthouse-bred film community that’s celebrated his work. In the tranquil Allandale neighborhood he calls home, he’s able to work late into the night, the stillness broken only by bands of roving cats outside his house. Because of the peace of mind it’s afforded him, Hertzfeldt considers moving to Texas one of the best decisions he’s ever made. “If any creative person has that space and has that quiet, where they can stay up til midnight without their cellphone and be alone with their thoughts, I think they’re gonna flourish,” he says.

But he also admits he doesn’t get to see much of the state. He still spends most of his days locked in a small room, his isolation broken by occasional walks he takes with his girlfriend, a compositing artist who works out of her own dark cave. Hertzfeldt talks about being “tethered” to his work, “trained like a dog,” “torturing” himself to get it exactly right. Although he says he enjoys a freedom in Austin that his Hollywood friends don’t, allowing him to spend entire years perfecting his films, he also characterizes his life as 1 percent pure creation, 99 percent tedium. Still, Hertzfeldt explores the importance of finding happiness and beauty in the small, mundane moments; even the copyright page for The End of the World mockingly chastises: “There is much more to life than this book.” It’s enough to make you wonder whether Hertzfeldt believes it himself.

When I ask Hertzfeldt if he finds some joy in the grind, he gives me the most unconvincing “Yeah, sure” ever recorded. “I don’t know if joy is the right word,” he says. “When I think of joy, I think of like a dog running through a field. I might be too tired to feel that. I think the carrot on the stick is that, in my head, these movies are perfect, and you get to that point where you’re like, ‘I think this could work.’ It’s like a golden egg on a velvet pillow, and now I just gotta edit it and do the sound mix—just deliver this egg and not drop it.”

In fact, Hertzfeldt is reluctant to take credit even for his own ideas, which he says just appear to him in the shower or other moments of isolation. “You’re washing dishes and suddenly there’s a scene in your head and you write it down,” he says. “I didn’t work on that. I didn’t struggle, or stay up nights figuring out how this movie’s going to end. It’s not something I feel like I’ve earned.” He shares this in common with director David Lynch, a proselytizer for transcendental meditation who’s likened creativity to waiting patiently by a stream to catch fish. Though, despite the often-meditative qualities of his own work, Hertzfeldt has never actually tried meditation. “I have my mother’s anxiety,” he says. “It’s a nuisance sometimes, but it’s something that gets me out of bed in the morning. I’m curious if meditation would not allow that to happen.”

Instead, he’s herded along by fear and guilt. “I’m 43, but I still feel like at any moment adults are gonna walk in the room and say you can’t do this for a living,” Hertzfeldt says. “You have to go work in a bank now. Cartoonist isn’t a real thing.” This is why he’s worked nonstop since college, forever mindful that he’s the rare breakout in an industry that’s become increasingly devalued—famous enough to get a major book deal for his late-night doodles, even.

When I tell him that he seems like he’s living the platonic ideal of the Austin creative life, the dream of everyone who’s ever moved here with notions of making art on their own terms, Hertzfeldt laughs. “I’m not hanging out in bars on the weekends, though,” he says. “I’m as much of a shut-in here as I was in California, which is part of the job. And I prefer it.”

“It’s a pretty good thing to complain about,” he says. “I feel extremely lucky to have somehow shaken through over the years, to be in this position where I can still do this, and it’s still fun, and there’s this audience, and it’s actually kind of lucrative now. I still feel like I’m getting away with something. And every day that I’m not working all night, really hard, it feels like I’m wasting time. It feels like I’m squandering this very lucky thing. It’s like, ‘How dare you? You’re set. You’re doing what you want to do. How hard is that?'”

- More About:

- Books