What makes the Texas woman unique? What makes her distinct from the demure Southern belle or the rugged, rifle-toting frontierswoman of the American West? As the novelist and Texas Monthly contributor Sarah Bird suggests in her 2016 essay collection, A Love Letter to Texas Women, maybe it’s that she combines the most potent qualities of both. Texas, Bird writes, is the province of tough, glamorous gals who “could give birth during a Comanche attack, help out when it came time to turn the bulls into steers, and still end up producing more Miss USAs than any other state in the nation.” Texas Monthly writer Mimi Swartz echoes this in her own essay “Why We Need Strong Texas Women,” discussing the misperception that the “smart, flinty, funny” mode of Texas women like Ann Richards, Barbara Jordan, and Molly Ivins is somehow the opposite of the “beautiful, sexy, and well groomed” Texas woman epitomized by Farrah Fawcett. “Anyone who bothered to carefully examine the lives of both groups would quickly see that some of their qualities overlapped,” Swartz wrote, “and that both flourished because they’d found ways to exercise power in a world still controlled by men.”

Unfortunately, the lives of Texas women rarely receive such careful examination. This is particularly true at the movies. Consider some of the most hallowed films in the Texas canon, such as Giant, Hud, The Last Picture Show, Tender Mercies, or The Searchers. Women tend to flit around the margins of these stories, playing the patient wives, the damsels in need of rescuing, or the objects of a man’s narcissistic desires. The women in these movies can find themselves abstracted into mere symbols, standing in for the Texas man’s domesticated restlessness, his potential for redemption, or the tangible stakes of his existential struggle. They seem to exist only to help the big, mythical Texas man sort out his life. Rarely is the Texas woman granted commensurate myths of her own. Mostly, she just gets to be miserable.

When the Texas woman does get her own story, it’s often about the dissonance between all her most extraordinary qualities and the empty, marginalized roles she’s nevertheless been forced to play. And frequently, that conflict explodes into violence. HBO Max’s Love & Death, which premieres April 27, is the most recent example of this venerable tradition. Based on the Texas Monthly story reported by Jim Atkinson and John Bloom, Love & Death tells the tragic tale of housewife Candy Montgomery, who had an affair with a man named Allan Gore in their small Dallas suburb of Wylie. When Allan’s wife, Betty, confronted Candy about it in 1980, Candy killed Betty, striking her 41 times with an ax. At her trial, Montgomery pled self-defense; even more controversially, her lawyers argued that Montgomery suffered from a long-repressed rage that had been involuntarily triggered when Betty confronted her. Candy Montgomery was a killer, there was no doubt about it. But maybe, they suggested, she was also a victim.

Love & Death sympathizes with Candy Montgomery, too. Elizabeth Olsen plays her with such charm and screwball vivacity that—even though Candy’s husband, Pat (Patrick Fugit), is a perfectly sweet if oblivious goofball—we can understand why Candy might feel restless and unappreciated. She’s bored and lonely, stuck in a suburban rut, and she’s tired of masking her growing emptiness behind the good mom’s guise of sunny subservience. “Men, they get to go to their jobs and live in their careers, and we just stay home,” Candy sighs in the show’s first episode. “And God . . . that’s supposed to be enough.” When Candy later shares her discontent with Pat, he just shakes his head and sighs, “Candy, you always want more.” Like the jury that acquitted her, we can’t help but feel a little sorry for her, even knowing where all this ends.

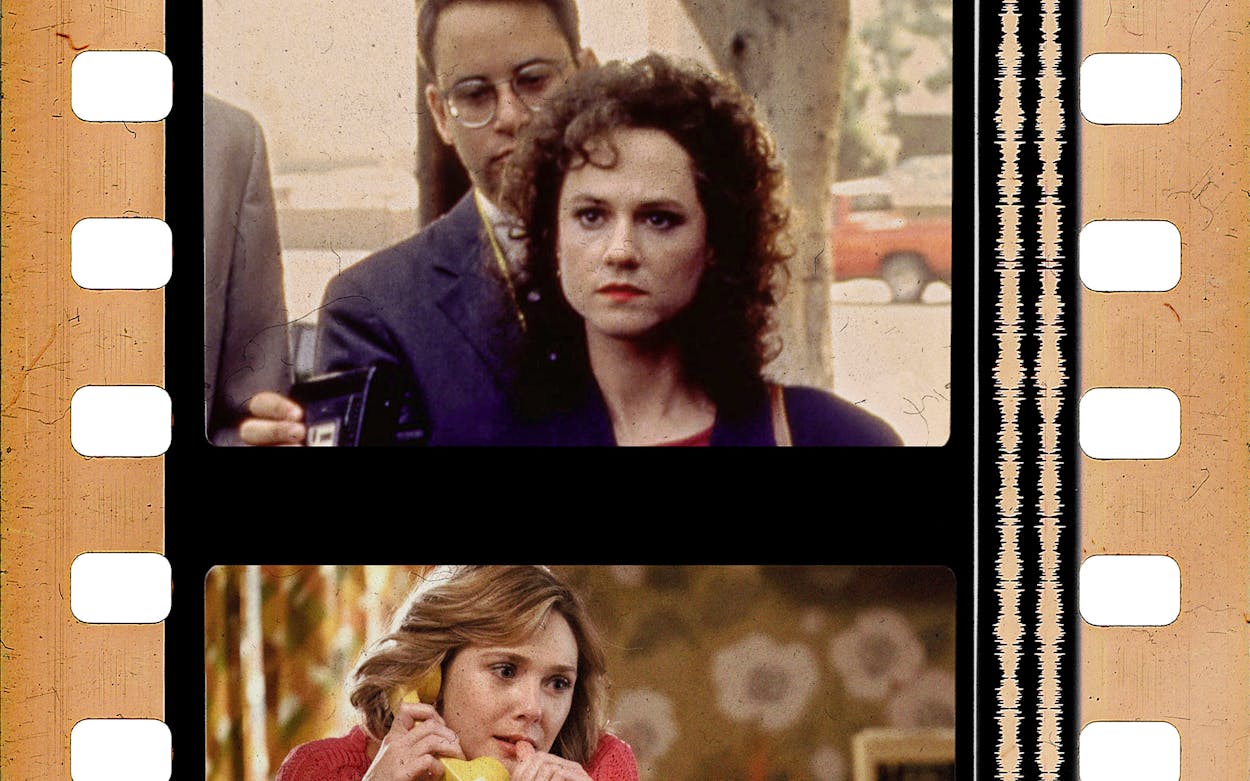

Love & Death would make for a pretty good double feature with another Texas true-crime story that premiered on HBO almost exactly thirty years earlier, the 1993 movie The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom. (Unfortunately, it isn’t currently available to stream, but at least you can still buy the DVD.) Starring Holly Hunter in a role that won her a well-deserved Emmy, Positively True adapts the tale of Wanda Holloway, the Channelview homemaker who was convicted in 1991 of attempting to hire a hitman to kill Verna Heath, the mother of a girl whom Holloway believed had stolen her own daughter’s rightful place on the school cheerleading squad.

Like Candy Montgomery, Wanda Holloway was an outwardly lovely person—a devoted mom and God-fearing woman who was well-known to her neighbors for playing the piano at her church. And, like Candy, Wanda wanted more. She was the kind of wily yet well-manicured woman that Mimi Swartz wrote about not just in her essay but in her original reporting on Holloway’s case, where she described Holloway as a relentless social striver who seemed to hold herself above everybody else in her dead-end small town. When her own life seemed to plateau, Holloway refocused her ambitions on her teenage daughter, Shanna, insisting that she become a cheerleader—for Texas girls (and their mothers), the ultimate position of power. And when her dreams were thwarted, Holloway was driven to murder, too.

Well . . . attempted murder. Holloway outsourced finding a killer to her former brother-in-law, Terry Harper, and it’s only because Harper immediately ran to the police that tragedy was ameliorated into something that hews closer to tragicomedy. This is the tack that was taken by Positively True’s director, Michael Ritchie, and screenwriter, Jane Anderson, who ditched a straight retelling of Holloway’s case (something that had already been done anyway in ABC’s deadly earnest 1992 TV movie Willing to Kill: The Texas Cheerleader Story). Instead, the filmmakers used the story to spin a broader satire of the media blitz that seized on the “Pom-Pom Mom,” turning Wanda Holloway into just one of the many “crazy women”—like Lorena Bobbitt, Amy Fisher, Tonya Harding, and Pamela Smart—who were fed into the ravenous maw of supermarket tabloids.

Positively True may be a comedy, but it takes Wanda Holloway seriously. The film’s closing title cards inform us that nearly all of the dialogue has been drawn verbatim from police tapes, court transcripts, and other interviews from the public record. Most of the scenes were even shot in the Channelview locations where the events took place. (After all, nothing underscores the banality of evil like plotting a murder in a Grandy’s parking lot.) Hunter lends her performance an equal authenticity, playing Wanda as someone you’d probably cross the street to avoid, but who could easily live next-door to you—which is precisely what makes her so unnerving. “You can write her off as a freak,” Hunter told the Chicago Tribune in 1993. “But she has seeds of fears and desires that are real, that everyone has in them. It’s just that they’ve been exacerbated, tormented, and inflamed in her.”

This isn’t to say she isn’t terrifying. Hunter plays Wanda like a shark in shoulder pads, her syrupy Georgia drawl sharpened into a piercing Texas twang that Wanda uses to steamroll over everyone, often speaking at such a rapid clip that her diphthongs come tumbling out in a burbling, Boomhauer-esque mess. She’s even scarier when she smiles, baring her teeth like a hostile primate beneath two slashing lines of lipstick, then holding it tight until it becomes a rictus mask of Southern politesse. When Wanda laughs, it’s just as mirthless—and rarely is prompted by anything funny. She only gets truly giddy when she’s conspiring to kill with Harper (played by Beau Bridges with his usual beery affability), weighing whether to kill Heath and her daughter, or to just go for the cheaper option of letting the emotional devastation of her mother’s death wipe the teenage girl out. “The things you do for your kids, gawd!” she exclaims, before bursting into manic giggles.

It’s a funny, fearsome performance, one that taps into the latent fury lurking beneath many a Texas woman’s obliging, “bless your heart” veneer. Yet just as Love & Death does for Candy Montgomery, Positively True finds some sympathy for Wanda Holloway—or at least some pity. It shows us the desperation that drove her dark compulsions. If the film has a thesis statement, it’s delivered by Swoosie Kurtz as Marla, Harper’s abused, psychologically damaged wife, when she screams, “Crazy men make crazy women!”

In this case, there are plenty of men who have “made” Wanda, including her religiously strict father, who forbade her from trying out for cheerleader because of the skimpy costumes; her ex-husband, Tony (Gregg Henry), who’s always late with the child support and is usually seen in bed with his newer, younger wife; and Wanda’s current, much older husband C. D. (Eddie Jones), a pliant lump who’s mostly seen silently cleaning his guns and rolling his eyes whenever she asks for more money. There’s also Harper, who pretends to be Wanda’s friend and confidant while he’s secretly recording her for the (all-male) cops. There seems to be a vast confederacy of men who have not-so-secretly held sway over Wanda Holloway’s entire life, Positively True suggests. They’ve conspired to relegate Wanda to the sidelines along with all the other women, leaving her to fight just for the privilege to cheer them on.

It’s tempting to say that the kind of oppression that drove both Wanda Holloway and Candy Montgomery to madness belongs to the past. I’d like to agree with Mimi Swartz, just in general, but also with what she wrote in her “Strong Texas Women” essay when she said that “Texas has become so much more connected to the rest of the country and the world, and women are, maybe, not quite so thwarted that they have to obscure their dreams and ambitions behind costumes and pointed humor.” I’d also like to believe that whenever those ambitions are challenged, they no longer feel compelled to blow up their lives just to wrest some control over them.

Yet given that we’re still producing shows like Love & Death, clearly there’s something about these stories that continues to resonate with that modern audience—and maybe, unfortunately, especially in Texas, which lately seems hell-bent on giving its women even less autonomy. Today’s Texas woman has a far greater breadth of opportunities and more diverse role models, it’s true. They aren’t so beholden to traditions or the social obligations that once might have left them trapped in unfulfilling lives in service to men. Still, perhaps it’s worth the occasional reminder of just how far they’ve come, and how much they have to fight still. We could definitely use more movies about the Texas woman’s struggle—and maybe even some ones where that struggle makes her into a hero rather than another villain.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television

- Film