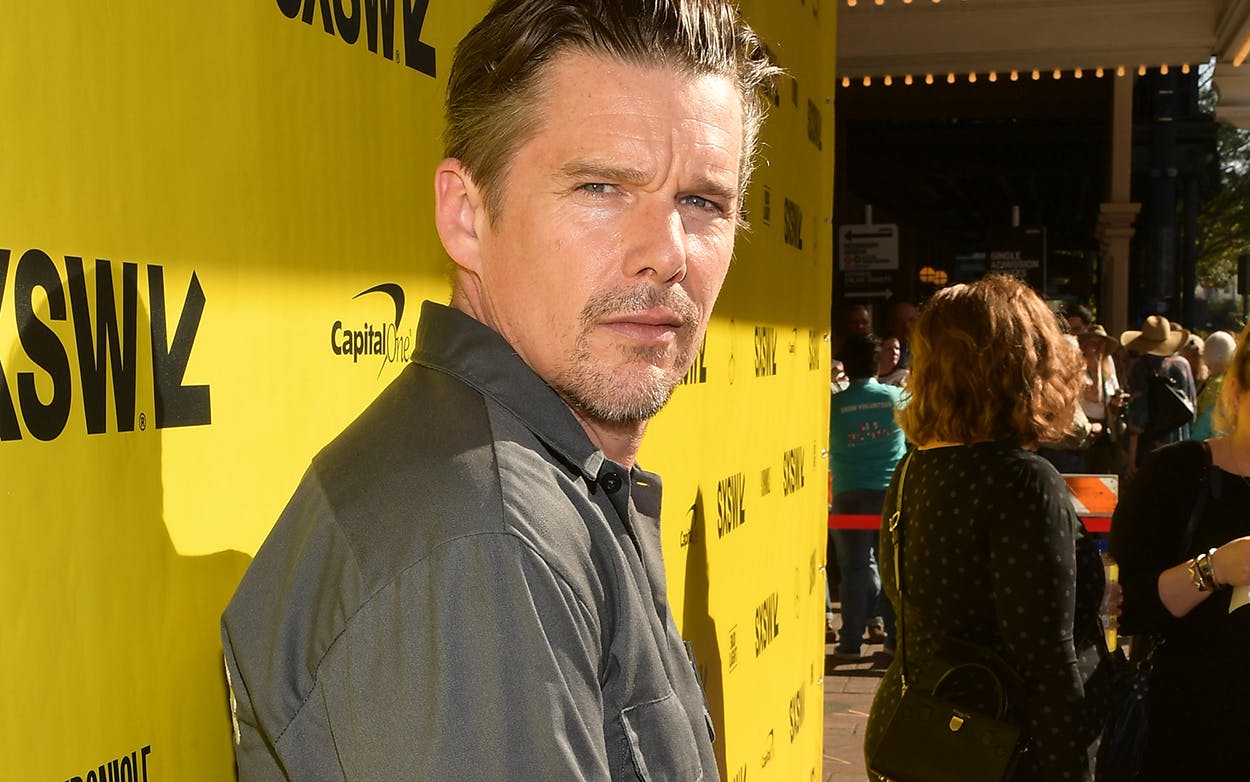

While the mikes were being positioned and tested for Ethan Hawke’s appearance on the National Podcast of Texas, the actor and director took us line by line through Blaze Foley’s “Oval Room,” a protest song written about Ronald Reagan.

He’s the president, but I don’t care

He’s a businessman, he got business ties

He got dollar signs in both his eyes

“It could be about Trump, right?” Hawke asks. “It’s such a gut punch. It’s like he knew.”

Hawke was in Austin promoting the South by Southwest screening of Blaze, his new biopic about Foley, a wildly talented but notoriously self-sabotaging singer-songwriter based in Austin who ran around with Townes Van Zandt, had a song recorded by Merle Haggard, and helped define Austin’s outlaw country scene. Foley once declared, “I don’t wanna be no star, I wanna be a legend,” and while he was neither before his death in 1989, he has steadily earned cult status in country and folk circles: Lucinda Williams and Kings of Leon have written songs loosely based on Foley’s life; John Prine, Lyle Lovett, and the Avett Brothers have covered his songs. But Blaze, which is expected to see a theater release later this year, is perhaps the biggest step yet in Foley’s posthumous renaissance. Hawke based the screenplay on a 2008 memoir from Foley’s longtime partner Sybil Rosen, who lived with Foley in a Georgia treehouse before he went off to Austin, and enlisted a pair of musicians trying their hand at their first prime-time acting gigs: singer-songwriter Ben Dickey as Foley and Bob Dylan guitarist Charlie Sexton as Van Zandt.

For Hawke, Foley is a stand-in for scores of artists who’ve navigated the complicated crossroads of brilliance and recklessness, but it’s also a chance to tell another only-in-Texas story. Hawke’s got a soft spot for the state; he was born in Austin, spent summers in Fort Worth after his parents divorced, and has worked throughout his career with Austin director Richard Linklater, most notably on the Before Sunrise trilogy and the twelve-years-in-the-making Boyhood.

Here—from the larger, unabridged conversation—Hawke addresses casting Kris Kristofferson, the modern state of the film business, and why he’s never moved back to Austin.

Texas Monthly: The Blaze legend is steeped in duality. He was a hothead and a narcissist, but also a deeply loyal friend and lover. That had be a challenging thing to depict.

Ethan Hawke: I saw the movie as kind of two love stories. One is with Sybil Rosen, and within that story, this physical place where creativity and love intersect: the treehouse. It’s a place of creativity. But creativity can also stem from narcissism, self-loathing, and self-destruction. And I kind of used Blaze’s friendship with Townes to represent that side of his creativity. It’s two circles, and there’s this push-and-pull between the negative manifestations of the ego and a positive one.

TM: Even though it’s based on a true story, you’ve suggested that you approached Blaze’s life as a vehicle to tell a larger, maybe more universal, story.

EH: I think if you see Raging Bull, that movie is not about Jake LaMotta. That’s a work of art that uses the story, the legend of Jake LaMotta, to tell you a story that seems somehow more important to the filmmakers. For me, I had this friend, Ben Dickey, who is a musician, and I saw his struggle firsthand. His band in Philly did okay. I would go see them in New York, and he would sleep on my couch after. And I used to think, “Wow, I got Neil Young sleeping on my couch.” And then I watched the industry kind of punch Ben in the teeth, and I started to think about Blaze’s story. That story is the stand-in for all the people we know in the arts who didn’t quite get their due.

TM: But you decided to take some liberties—as all biopics do, I suppose.

EH: We live in a time period where the documentary is king. Documentaries are possible like they’ve never been before. But the facts here are not as interesting to me as the legend. They’re interesting to his family and people who loved him, to his friends and people who suffered for him. But I probably went about this similarly to the way Lucinda Williams wrote “Drunken Angel” about Blaze. Broad strokes.

TM: And Lucinda has said that in retrospect she came to the conclusion that “Drunken Angel” could have also been about Townes. It’s that universal.

EH: Right. And how many Townes types are there in every city? If you spend your life in the arts, you’re going to run into somebody that you believe in and you know as a poet, a painter, a dancer of the first order. But why are they so mad at themselves? What is that connection between pain and creativity? Is it just self-destruction? And then we watch the flag of mediocrity get raised and you watch kind of lame talents get paid millions of dollars. And you wonder what that’s about. Why does the world spin that way?

TM: One of the film’s most affecting performances is a brief turn from Kris Kristofferson as Blaze’s father. Why Kris?

EH: First, Kris sits at the top of that totem pole for me as far as a man who’s really willing to stand up for his beliefs, a man who is willing to fight, and yet also a man who’s vulnerable enough to be outwardly kind and gentle. And one of the things that I love about the South and Southern men is their ability to not be just one thing.

He’s got just one line in the film, which he repeats several times.

EH: Yeah. “Got any cigarettes?”

TM: So in this role the symbolism you wanted him for is wholly conveyed through his weathered face.

EH: That outlaw thing, the Southern bohemia thing? It’s in his eyes, almost just in his eyes. And we left it like that. It’s very meaningful to me for him to have been there. I’m very grateful. He knew I wanted him to do it. And he’s at a very interesting moment in his life, with his memory leaving him the way it has. But Kris, the man, is still there. The artist is still there.

TM: In an interview about ten years ago, you raised the idea that at some point we may be able to order up a film from some limitless bank on our television and that maybe films won’t be something we have to go to the theater for. It seems prescient now because at that point Netflix was mostly streaming some bad TV shows and a handful of bad movies. But you also couldn’t have known just how quickly and dramatically the film business would change.

EH: It happened fast, right? When I was first starting in movies, I longed for the seventies or the fifties. I romanticized those eras. But when you’re young, you don’t realize time is going to keep moving and things will keep changing. You think time is frozen. When I was first on a film set, they didn’t have any monitors. I remember Peter Weir would be seated right underneath the camera while we were filming Dead Poets Society. It’s been fascinating to watch this industry change.

Shortly before I did that interview, I saw Celebration. It was a Danish film that they made with what was basically a toy camera. And I remember talking to Rick Linklater about it. We both called each other, like, “Everything’s going to change now—how movies are made, packaged, delivered.” But the status quo is now really erupting. I’m very curious about how art films can find their rightful place in the national dialogue. Because unfortunately what’s happening right now is the only movies that people are really going out to the movie theaters to see are movies like Black Panther—a wonderful movie and it’s a wonderful moment. But we used to go to the movie theater to see Claire’s Knee. Or Wings of Desire. I went to the theater to see Paris, Texas. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was nominated for Best Picture and was a commercial success. When was the last time we had a flat-out really challenging drama like that that was a commercial hit?

TM: I would think you come into this new era with an advantage in that you were part of the old system. For instance, in music, people who made records when the labels were still spending money are in a much better position to have long careers than artists who’ve had to piece together a name for themselves without the marketing budgets and tour support the labels used to offer.

EH: Sure, because they already have a place at the table. Yeah, they’ve already been served; the plate has been set out for them.

TM: And you were part of the old system.

EH: I remember I read an interview with Dylan where he said it used to be the record label came to see you, you got signed, and it was like you were a made man. You’d made it. And then he could just think about what art he wanted to make. And now you get signed, but then you’re cut nine months later when it doesn’t sell. Or that record company goes under. There’s no plateau to reach. It just simply doesn’t exist.

And you’re right. I’m better off. I already have existing relationships with filmmakers. I already have relationships with studios. Think about a movie like Slacker. When Slacker came out it was an event, not even that it was necessarily good.

TM: Or easy to watch.

EH: It’s difficult to watch. It’s a punk rock movie and it’s asking a lot of the audience. But the story I first heard was not that Slacker was good or bad or punk rock or interesting or incendiary or whatever other things it is. The story was that he made it for $16,000 and spent his own money. And so you kind of wanted to go see it just to see how that was even possible. Movies had always been for Steven Spielberg and Howard Hawks. It was unreachable as an independent art form. But now there could be outlaw movies. And now $16,000 is a big budget, right? But you can’t show it because everybody and their mom has a movie on their website. So getting it seen is the struggle.

TM: They probably didn’t let you make Blaze because they thought it was going to make a fortune.

EH: No. Expectations are humble. But one thing my life has taught me is that those are the things that have a chance at lasting. Before Sunrise is a movie that was a perceived failure for the first few years after its release. Gattica, the same thing. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, same thing. Some of the movies that people most often talk to me about are those movies. Yeah, there’s Training Day and Dead Poets Society, and those are big movies with big studios behind them. And that’s certainly exciting. But some of the studio movies I’ve done that people thought were going to be huge? Nobody on the street ever asked me about those.

TM: And because it was so ambitious, we couldn’t have known Boyhood would turn into what it did, right?

EH: Boyhood was made with the same ethos that Blaze was. That was an exercise of Rick really pushing himself to be the best filmmaker he could be and really think forward. Rick was saying, “You know what’s possible now? It’s possible to make a movie over 12 years. I could do this if we all were really patient.” And that was a beautiful thing to be a part of because we were part of something absolutely original.

TM: The role of the actor as a celebrity has also changed dramatically. What actors do offscreen seems as important, if not more so, than what they do onscreen.

EH: When I was a kid, Robert Redford never gave an interview. Robert DeNiro never gave them. Warren Beatty released Reds, one of my favorite movies, with no press.

TM: And you’ve probably done seven interviews today.

EH: I mean, I love that Beatty could say the movie speaks for itself. I wish I could say the movie speaks for itself. If I said that? It’s pack up your bags. And that’s frustrating for all of us. There’s just a tremendous amount of noise. And I think one of the things our political system has taught us is that it’s so easy to sell newspapers. You say somebody’s got small hands, and all of a sudden you get a lot of press. You say somebody is bleeding from a face-lift and all substantive dialogue evaporates. My stepfather was a beautiful man. He was talking to me about acting and he said, “Just be careful. There’s two really easy ways to get attention: you can shoot somebody or rip a woman’s top off. And everybody will turn and look. We should be better.” Neither one is the role of the artist. You know that’s not good enough. And so I think we’re all struggling with that. Most of us can’t help it. I drive down the highway and there’s a bad wreck. I slow down to look, too. I don’t want to. But I do.

TM: You were born here, you worked here so often, but you’ve never moved back to Texas.

EH: I’ve thought about it many times. I was thinking a lot about it today, about how life moves in strange ways. You know my mom is here for the premiere of Blaze. I was born in Brackenridge Hospital, which is where Blaze died. And she really wanted to be here because this is an important moment in my life. And so she’s here, and I was thinking about when I almost moved here right after I made Gattica. Linklater and I were really good friends and I really was inspired by not just Rick, but by Rick’s friends—the people that he was introducing me to in the scene, and not just the film scene. I met people in the music scene, painters and people in cool punk rock theater companies. My girlfriend at that time was a grad student at the University of Texas, for social work, and I really wanted to be here. I came here. My mom met me here because I was going to buy a house. I was about 25 years old and I was set on moving back to Austin. And then this girlfriend told me she was in love with another man and broke up with me. So I didn’t want the house anymore. I kind of had this fantasy that we were going to live in. I had this idea of a life that she was involved in. I went back to New York to lick my wounds. And it’s one of those weird forks in the road where I could have gone either way . And then, when my first marriage fell apart, I just knew I was going to move back to Austin. But I forgot for a moment that I couldn’t bring my kids. You know, I was like, “Oh and their mother loves them too? Wow, I can’t do that.”

TM: But you got to make so much of Boyhood here, across twelve years.

EH: Sure. And all the other movies Rick and I worked on that didn’t get made. But I’ve got a lot of friends here and have a life here without living here. One of the biggest challenges of making Blaze is how badly I wanted to shoot it here. I called Rick Linklater and I was like, ‘Hey, you know I got five cents to make this movie. Can it be done?” And I realized really quickly that I had two options. I could make the movie somewhere else—New Mexico or Louisiana—or I could not make the movie. But almost every shot in the movie is based on a location I was originally scouting for in Austin. I wish Texas would give better kickbacks to make it possible to shoot here, because one of the most moving things that made me want to make this movie was this story that circulated that on the very night of Blaze’s death, he was carrying a chrysanthemum down Congress. He was talking to it. And I thought, “What the hell was he talking about?” So we set out to make a movie and figure out what he was talking about.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Ethan Hawke