Texas Monthly has been around for fifty years, and it feels like Tommy Lee Jones has been old for nearly all of them. He’s one of those actors whose fame is bound up with his age; a Google search for “Tommy Lee Jones + craggy” returns more than 70,000 results. For many audiences, Jones blinked into existence somewhere around the early nineties, as the stony face of authority seen in movies such as The Fugitive and Men in Black, or on TV as Lonesome Dove’s Woodrow Call.

He’d been acting for two decades before that, playing a lot of villains and other violent men whose menacing eyes could turn suddenly misty and wounded; who could disarm you with a laconic witticism delivered in a Texas drawl from his unsmiling mouth. But Jones only achieved his fullest, prickliest bloom once his features had been wizened to match the dour wisdom they contained, and the roles started to follow suit.

In 1970 you might have caught the San Saba native—then billed as “Tom Lee Jones”—making his big-screen debut in the three-hanky phenom Love Story, provided you hadn’t run to the bathroom during his few, fleeting scenes. Years later, Love Story author Erich Segal revealed that he’d based its protagonist, the preppy hockey player Oliver Barrett IV, on an amalgam of Jones and Jones’s Harvard roommate, Al Gore, whom Segal had met when they were all living in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Like Barrett, Jones was a jock with a poet’s soul, a hardscrabble footballer from the roughneck wilds who loved Shakespeare and Brecht. But the movie role went to Ryan O’Neal. Jones just pops up to purr some light misogyny around a cigarette, leaving little lasting impression beyond a sort of retroactive novelty.

Back then, you’d likely only heard of Jones if you were deeply embedded in the New York theater scene. If you were a homemaker or unemployed, maybe you knew him from the daytime soap One Life to Live, where he put in four years as Mark Toland, the suave Texas doctor who wooed women of varying levels of sanity.

Jones, although darkly handsome and cowboy-rugged, was no one’s idea of a traditional leading man, yet he spent his early years acting in art house romances and wooing Kate Jackson on Charlie’s Angels. In 1979 Jones—finally going by “Tommy Lee,” as he had growing up—even splayed himself across the cover of the showbiz tabloid After Dark, his feathered hair lightly tousled, his gingham shirt unbuttoned to the navel. Seeing that photo today feels not just incongruous but wrong, like stumbling across a secret box of Polaroids beneath your dad’s bed.

Jones’s beefcake shot was taken the year before his breakthrough in Coal Miner’s Daughter, where he finally earned the rave reviews that, along with his Emmy-winning turn in 1982’s The Executioner’s Song, only compounded the sense that he should be a bigger star than he was. But it was another decade before his career truly picked up steam, beginning with another Emmy-nominated performance in Lonesome Dove that, tellingly, saw him prematurely grizzled beneath a white wig and beard. Jones was simply born to be old. His star needed time not just to rise but to cool until it became harder and denser, with a far greater gravitational pull.

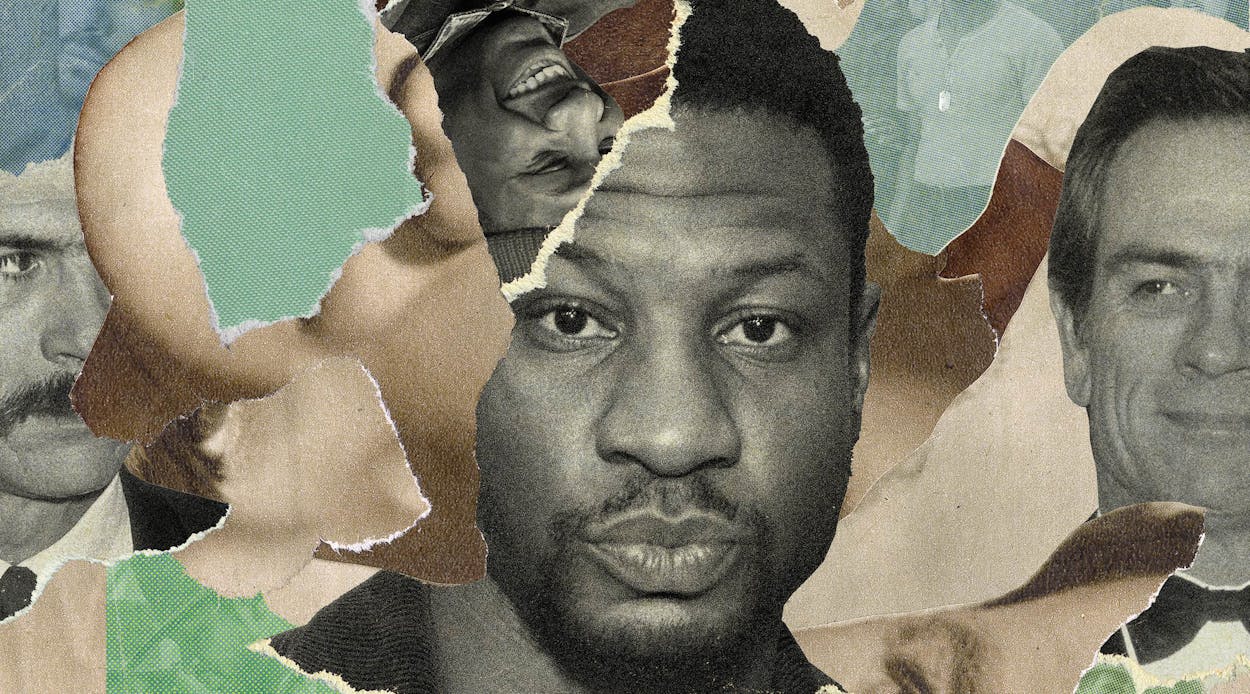

We don’t really give actors that luxury today. Most are shot out of the Disney Channel cattle chute and afforded the span of a TikTok to make or break it. So it’s all the more remarkable when someone like Jonathan Majors emerges thoroughly in command of his powers.

Like Jones, Majors is another scrappy, self-made Texan athlete who found his way to the Ivy League, going from a troubled childhood in the Dallas Metroplex to the Yale School of Drama, where Gus Van Sant handpicked him to star as a gay activist in the miniseries When We Rise. Unlike with Jones, however, it didn’t take years for Majors to find himself, or for us to find him.

Majors made an instant impression in indies such as Hostiles and White Boy Rick; then he left it all on the field with 2019’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco, delivering a tour de force performance as a sensitive artist who chafes against the prescribed roles of Black masculinity. He’s been doing meaningful work ever since, in Spike Lee’s Vietnam War caper Da 5 Bloods; in the revisionist western The Harder They Fall; in HBO’s social horror series Lovecraft Country; in this past winter’s fighter pilot drama Devotion. In 2023 Majors officially graduates to the A-list with heel turns in Creed III and the new Ant-Man movie, where he’ll play the next archvillain of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. He’s only just begun, but already he’s a boldface name: recognized, admired, anticipated.

You could say that Majors has benefited from how media has changed since 1970, now that getting your start in TV often means starring not in soap operas but in prestige HBO dramas, and the abundance of content includes a greater variety of smarter, riskier projects. But Majors’s mercurial ascent also feels uniquely attuned to our moment. What better avatar, after all, for a Texas whose cultural influence is increasingly defined by Black artists such as Beyoncé, Lizzo, Attica Locke, and Justin Simien? If Jones embodied the twentieth-century Texan as a taciturn lone (white) wolf, then Majors represents its diversified, urbanized present—more engaged, far less repressed. A signature Jonathan Majors move is the manful cry, wiping away tears that leak out over a face screwed up in defiance, usually before he explodes in anger. He’s less weary of the world than aware of how much pain is inside it, and he’s resolved to carry that burden.

But these two actors are also more alike than they might seem. They are linked by a work ethic that feels distinctly Texan, offering testament to the conviction that talent and discipline outstrip any coastal privilege. Both are serious-minded men driven to tell stories inspired by their roots. When Jones spoke (grudgingly) to Texas Monthly’s Skip Hollandsworth seventeen years ago about his West Texas–set directing debut, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, he declared that he wanted to capture his “home people” for an audience that was long prone to dismissing them. Majors has similarly talked about his desire to express an authentic Black American experience, and about how, for Lovecraft Country, he drew on the terrors of being profiled and harassed by Dallas cops as a teen. “As long as there’s pain within humanity, my culture, children, and the planet,” he recently told BET, “there’s something to be done.”

Majors is still young at age 33, still enjoying his own heartthrob phase of shirtless magazine spreads and guest-hosting Saturday Night Live. Yet he acts with such authority that these lofty aspirations seem not just attainable but inevitable, and already well in motion. We don’t need a decade or two to appreciate what he does. We can see it today—just as we will fifty years from now.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Acting Like a Texan.” Subscribe today.

Image credits: Jones: Barry King/Getty, Ron Galella/Getty; Majors: Michelle Quance/Getty, Robin L Marshall/Getty; Coal: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty; Jackson: United Archives/Getty; Harder: David Lee/Netflix/Everett Collection; Lovecraft: Eli Joshua Ade/HBO Max/Everett Collection

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Movies

- Tommy Lee Jones

- Jonathan Majors

- San Saba

- Dallas