A few days before Halloween, a small crowd of aging hippies gathered in an old Austin beer joint to hear an old Austin band play an old murder ballad. The bar—Dry Creek Cafe & Boat Dock—had been open since 1953 but was closing for good at the end of the month. The band—Freda and the Firedogs—had officially broken up in 1974 but the musicians had performed at various reunion shows over the years. Now they convened in the early afternoon of a blustery day on the creaky second floor of Dry Creek to play a song inspired by the bar, to make a video, and to say goodbye to a place and a time.

“I’m ready to roll,” said Bobby Earl Smith, who had set the whole thing up. The 78-year-old sat on a stool wearing jeans and a Stetson, his acoustic guitar in his lap. He had been the main songwriter in the Firedogs as well as one of the singers. Born in San Angelo, Smith had moved to Austin in 1965 to go to law school, then wound up hanging out at Dry Creek, listening to classic country songs on the jukebox like “Don’t Let Me Cross Over,” and dreaming of writing his own. He loved murder ballads like “Tom Dooley,” the number one hit for the Kingston Trio in 1958 in which the narrator stabs his girlfriend to death. So he wrote one in which a young man catches his lover cheating and stabs her to death too. “She’ll never go again,” he sang, “to the Dry Creek Inn.” Smith changed the name of the bar because he couldn’t find a rhyme for “cafe,” but truth was, Dry Creek rarely served food anyway. In the second verse, the singer notes that although he got away with murder, he too can never go again to the Dry Creek Inn.

To Smith’s right was Marcia Ball, a.k.a. “Freda,” who sat in front of an electric piano. Ball, age 72, was the lead singer in the Firedogs, and she wore jeans and an embroidered Mexican blouse. To Smith’s left was 76-year-old guitarist John X Reed, in dark sunglasses and a bright red shirt, a pink bandanna pushing back his long gray hair. He played a Telecaster through an amp. (The other two in the band, drummer Steve McDaniels and pedal-steel guitarist David Cook, couldn’t make the gig.) There was no stage, and the three musicians and their instruments took up about a third of the small room.

“What do you want to do first?” asked the video director, Jay Curlee. Smith replied, “Make Me a Pallet.” As the small crowd of spouses and old friends watched, Ball played the intro riff of the song that led off Freda and the Firedogs’ only album and began singing as Smith and Reed followed along and a hard wind gusted through the oak trees and into the open windows. The second floor of Dry Creek, which had been cobbled together years before out of various kinds of thin wood, seemed to list in the wind, which blew through several large gaps in the walls.

When Dry Creek opened it was a lonely roadhouse on the edge of Austin, surrounded by rolling hills. The joint was not much more than a shack with an upstairs deck. The clientele was mostly cedar choppers (laborers who cleared the ubiquitous cedar trees) and University of Texas at Austin students. The owner was an irascible woman named Sarah Ransom, who didn’t suffer fools, especially those who neglected to return their empty beer bottles when they ordered another round. When a customer once complained about the selection of songs on the jukebox, Ransom pointed to the door and yelled, “Get your ass out of here!” But regulars loved her, and the bar developed a steady crowd drawn by the laid-back, friendly vibe. Many patrons would come in the late afternoon, sit on the deck, drink beer, and watch the sunset across Lake Austin and the hills. In the past generation, though, the neighborhood changed drastically as the wealthy bought up land along the water and built gated mansions. The area became one of the toniest in the city, and Dry Creek, with its gray siding and faded yellow paint, stuck out like a hillbilly hovel. For years the current owner—Ransom’s 84-year-old son Jay “Buddy” Reynolds—turned down offers to sell, until early this year. As the final days neared, Smith got the okay to shoot a video.

Smith, Ball, and Reed ran through some songs they used to perform as Freda and the Firedogs, bantering with the small crowd. After Ball sang “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad,” she called out to her husband Gordon Fowler, who leaned against a wall. “Gordon, when did you start drinking here?” Fowler, age 76, answered, “Sixty years ago.” He paused. “No, sixty-five.” The crowd laughed. Fowler’s father Wick, the famed newspaperman and inventor of Wick Fowler’s Two-Alarm Chili, used to visit Ransom every Sunday morning, bring her a newspaper, and have a cup of coffee. When Gordon Fowler was a teen, Ransom would let him and his rock band practice on the deck, though she never booked any groups for actual shows. One of Fowler’s bandmates was a kid named Polk Shelton, who now sat in the small crowd watching the Firedogs.

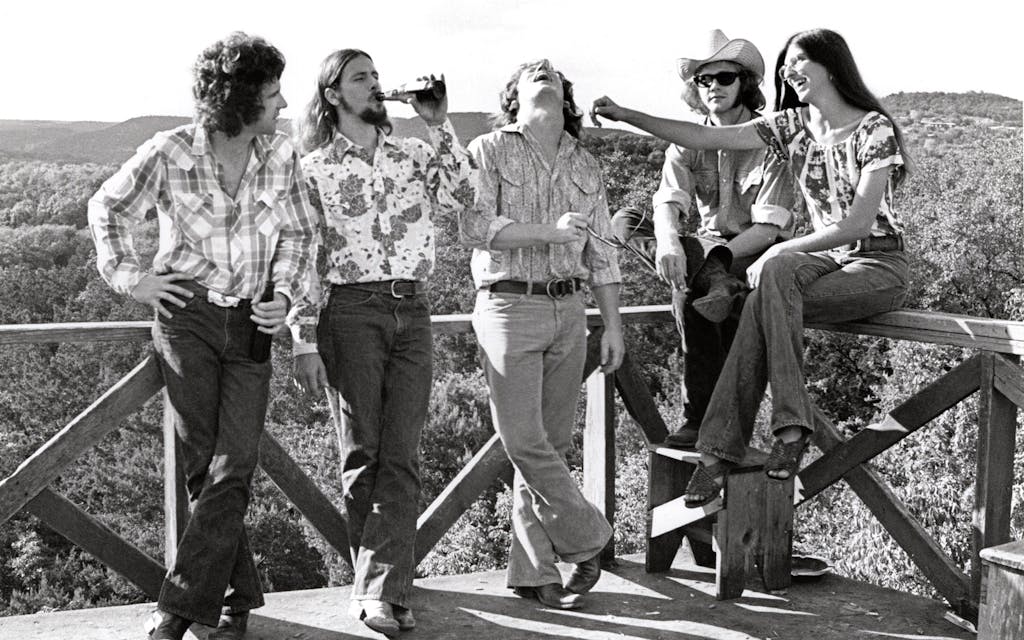

“Should I ditch the shades?” asked Reed. “No,” answered Curlee. “I dig the shades.” On the wall, the video crew had taped up ancient “Freda and the Firedogs” posters illustrated with four dalmatian puppies and Ball as she looked fifty years ago, wearing a cowboy hat and round, wire-rimmed glasses. Ball had moved to Austin in 1970 from Louisiana and met Smith. She was more into R&B than C&W, but Smith showed her some old country songs and soon they started the band. The Firedogs were early Austin slackers, doing their own thing: they tucked their shirts into their bell-bottomed jeans, wore cowboy hats on their long hair, smoked marijuana, and sang songs by Tammy Wynette and Merle Haggard. Soon the group was playing country music for hippies at the famed Armadillo World Headquarters beer garden and a bar called the Split Rail. In 1973 the Firedogs performed at a political benefit at the Broken Spoke, a hard-core honky-tonk where most hippies feared to tread. But that night the Firedogs brought in five hundred longhairs; owner James White liked what he saw and began booking the band steadily. Willie Nelson gets most of the credit for bringing together the hippies and the rednecks and birthing progressive country, but Freda and the Firedogs were doing it too, and in an understated, soulful fashion. You can hear it on their album, which was full of steel guitar, smooth harmonies, and Ball’s clear, sweet voice. They sound like old Austin: mellow, rootsy, idealistic, and quite possibly high.

The wind burst through the trees with a roar as Reed, who for the last few years has led his own country band, started playing “Honky-Tonk Man,” and the others joined in. He is a much more confident guitarist today, having spent the interim decades playing guitar with dozens of country, blues, and R&B musicians. Likewise, after the Firedogs broke up, Ball became a well-known blues and R&B pianist, releasing seventeen albums and winning numerous awards. She sang “Someday Soon,” the old rodeo song, and got tears in her eyes. “That one makes me cry,” she said. Smith sang “Don’t Let Me Cross Over,” the old song he used to play on the Dry Creek jukebox, while Ball sang harmony. Though in 1984 Smith actually began using his law degree, becoming a local defense lawyer, he spent many of the interceding years also performing music and released three albums of his own.

Finally, the Firedogs were ready to record “Dry Creek Inn,” their best-known song. Smith told the story of how he had written it with pianist Ron Howard, who sat in the audience. Smith said that back in 1972 he had heard the sound of a pump organ in the apartment complex where he and his wife Judy lived; he followed it to find Howard fiddling around with a Bee Gees song. Smith liked the way Howard played and asked him to collaborate. He gave him the lyrics to his murder ballad and some other songs to think about, folk ballads like “Tom Dooley” and “Long Black Veil.” Howard returned with an entirely unconventional melody that flipped back and forth from a minor chord to a major one. It was one of the most melancholy melodies Smith had ever heard, and it transformed his murderous words into something utterly sublime.

Reed began the song, Ball came in on piano, then Smith on acoustic guitar. You could still hear San Angelo in Smith’s voice as he sang the first line: “The first snow of winter and I knew where she would go.” By the end of the verse, he had killed her:

I caught her and I taught her

I taught her what was right

I taught her with the sharp end of a knife.

It’s a short song, and when the last sounds of Reed’s guitar died away a minute later, the musicians’ friends all applauded. Ball said she had hit a bad chord and they started another take but soon stopped; it was too fast. They tried again, and this time all three seemed to tap into the lonesome feel of the version they had recorded in 1972. Ball sang harmony with Smith, and toward the end, the two locked eyes as they sang together. Both smiled. “We can do it again,” said Ball, clearly enjoying the moment. “I can do it all day if you like.”

They did one last version, then the band ran through a few more old covers and wrapped up. Ball left the piano and Reed set down his guitar and walked to the back of the room. Smith announced that Howard wanted to do his version of “Dry Creek Inn” in the key in which he had written it 49 years before. Smith retreated to a chair along the wall while Howard sat down at the piano. It took him several tries to make it all the way through, and while Howard played, Smith sat with his guitar in his lap. At one point he rested his chin on the guitar and closed his eyes. A half smile appeared on his face. Smith sat listening to Howard play the ethereal melody that carried his dark words, thinking of a time when he and everyone else in the room was young and Dry Creek seemed indestructible. Now, like the song’s protagonist, none of them would ever go again to the Dry Creek Inn.