ANY GOOD PARKING SPACE WILL NOT SUFFICE: Rene Zellweger pulls her Volkswagen Jetta right in front of her usual outdoor table at Authentic Cafe in Los Angeles. The unforgiving meterthirty minutes for a quarter, twelve for a dime, six for a nickel, one hour maximumwill require vigilance, but Zellweger need not worry: A waiter is on the case. He’s a one-man advance-warning system, keeping an eye out for the meter maid’s car. And though most waiters and waitresses spend their time collecting cash, this guy gives it out, feeding her a steady supply of quarters when she comes up short. Then, after Zellweger has gone through all the change, the meter maid passes by and… apologizes for interrupting her lunch.

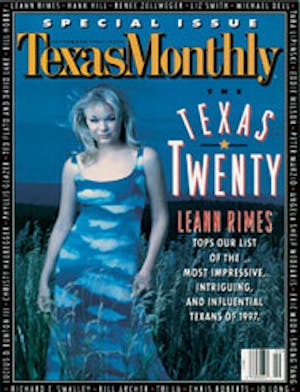

Ah, Hollywood. If the genuflecting hasn’t already tipped you off, the 28-year-old Zellweger is an actress. And not just any actress, but one of 1997’s hottest actresses, the female lead in Jerry Maguire, a $270 million hit that also happened to be the only studio film nominated for the best picture Oscar this year. Allegedly, everyone from Mira Sorvino to Winona Ryder coveted the role of Tom Cruise’s love interest, but Zellwegerat the time a practically unknown native of the Houston suburb of Katygot it, and then shined in it. It was a rare part for a woman in a commercial film, which is to say that it was well written and required neither blowing things up nor watching some male star do so. Since then Zellweger’s name has been rolling off the tongues of critics and Hollywood insiders who see her as a hot young talent with an unusual presence that compares with the likes of Jean Arthur and Katharine Hepburn. The estimable Jack Matthews of Newsday called her “Hollywood’s discovery of 1996, and its star of tomorrow.”

Zellweger, however, is hardly a one-film wonder. Just as she was winning raves for her star turn in Jerry Maguire, she was wowing independent film fans with an overpowering performance in the art-house and festival hit The Whole Wide World; together, the two parts earned her the National Board of Review’s Best Breakthrough Performer Award for 1996. One year later she has the lead as a renegade Hasidic wife in the indie film Price Below Rubies, and she recently signed on to a major studio project, One True Thing, in which she stars alongside Meryl Streep. There are at least ten Web sites devoted to her, which is way more than Joey Lauren Adams (the Chasing Amy star Zellweger is sometimes mistaken for) but way fewer than Jewel (the wildly popular female folksinger Zellweger is nearly always mistaken for). And in perhaps the ultimate stamp of approval for a budding show biz icon, Zellweger is on the cover of September’s Vanity Fair, having previously appeared, with fellow Texan and hot young thing Matthew McConaughey, in a group shot for the magazine’s annual Hollywood issue.

The waiter at the cafe, rest assured, knows all this. At the end the day when lunch is over, he finally tells Zellweger how much he admired her work in Maguire and asks about Rubies. It turns outwhaddaya know?that he’s an actor himself, with a movie hopefully headed for the Sundance Film Festival next year. (Ah, Hollywood.) Zellweger claims not to notice such fawning, or at least the fact that it’s unusual. “A lot of times I’ll just forget [that I’m famous],” she says. “I’ll think, God, that was the nicest thing to do! People are getting nicer in L.A.! Now they treat me like people back home always treat me.’” Indeed, the courtesy and levelheadedness that come with Texas roots are important to Zellweger, who professes to be mortified by the thought that anyone would say she’s gone Hollywood: “People are like, God, your life has changed,’ and I’m like, No, not really!’”

It’s true enough that Zellweger isn’t Hollywood wealthy. Her rsum is filled almost exclusively with low-budget, low-pay movies. And as for Maguire … well, there’s a reason why you don’t hire Winona Ryder when your leading man gets $20 million. “I was the bargain,” Zellweger says. “I was the one where they said, If we hire that girl, we’ll save money.’” Likewise, she still lives in the same garage apartment she rented when she moved to L.A. in 1993, and she is nowhere to be found on the party and premiere circuit. When she does join the rest of the brat pack at something like the MTV Movie Awards, she isn’t exactly the type to break out the brand-new Mizrahi gown and the borrowed Harry Winston jewelry. There are unflattering paparazzi shots of her to prove it.

Yet actresses do not end up in Tom Cruise and Meryl Streep movies by accident. Zellweger portrays herself as someone who is oblivious to the vagaries of the movie businesssomeone who doesn’t read the trades, doesn’t know who the players are, doesn’t have a long-term career strategy. Her only ambition, she says, is to find her next great role. Certainly she seems more interested in doing good work than becoming a “movie star,” which is convenient, as genuine talent, which Zellweger definitely has, is entirely unrelated to star quality, which she may not have. But she has agents and managers like any other actress, and she can charm, compete, and manipulate like them as well. In an age when young actors have their own production companies and directorial ambitions before they’ve made their second film, the notion of Zellweger as a naf who cares only about her craft is appealing, but it somehow doesn’t wash.

So who is Rene Zellweger? She is not only a first-generation Texan but also a first-generation American: Her dad, Emil, an engineer, is Swiss, and her mom, Kjellfried, a nurse, is Norwegian. All reliable evidence suggests that she did not dream of being on the silver screen from day one. Growing up in Katy, she was more jock than drama queen, running track and cross-country and playing basketball. When she left Katy to attend the University of Texas at Austin, she wanted to be a writer. As an English major, she says, “I went all over the place, from Puritanism to British lit to the Victorians, to Hawthorne to Faulkner toname it.” When she began to act at age twenty, it was to pay the bills; doing commercials for beer companies and fast-food restaurants may have been an unglamorous grind, especially with all the trips to Dallas to audition for parts she didn’t get, but it was preferable to work-study or the lucrative but equally unglamorous time she spent as a waitress in the Austin topless bar Sugar’s. Austin clearly shaped Zellweger in a way that Katy didn’t. It’s fashionable if you live in Austin to have little good to say about the place, but if you’re in New York or L.A., it’s paradise lostand so it is for her. The reason she hangs out at Authentic Cafe is that she loves the salsa; she’s prone to rhapsodize about the Austin food (chicken tacos from Gero’s, black-bean tacos from Magnolia Cafe) and clubs (the Continental) she misses. Austin is where she immersed herself in movies; as a UT freshman she lived at the Dobie Center dormitory, which meant easy access to the indie films playing in the theater downstairs. Austin is where she acquired her dog, a half-collie, half-retriever named Dylan. Austin is also where Zellweger experienced her political awakening: When I informed her that the newly elected city council is made up entirely of environmentalists, she rose to her feet, gave me a high five, and dreamily talked of how Barton Springs must be safe again.

And Austin is where Zellweger cut her teeth as an actress. Her first film was 1993’s Dazed and Confused; she was a mere extra in Richard Linklater’s high school reminiscence, though her wordless scene, strolling past Matthew McConaughey’s character as he ogles a group of girls, has since been singled out by Entertainment Weekly as an auspicious cinematic moment. About the same time as Dazed, she and McConaughey nabbed starring roles in The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which debuted at Austin’s South by Southwest Film Festival in 1995; a year later theatrical distribution rights were picked up by Columbia/TriStar Home Video, just before McConaughey hit with A Time to Kill and Hollywood was buzzing about Jerry Maguire. As several publications have reported, however, Columbia/TriStar made no effort to release the film, and several people associated with it blamed Zellwegerthe theory being that a shrieking role in an offbeat slasher flick wouldn’t reflect well on her now that she’s a serious thespian. Zellweger denies it: “I don’t have anything to do with it,” she told me, pulling out a folded-up copy of the article on the contretemps that ran in this magazine (Reporter: “Saw Loser,” March 1997). “It’s kind of obvious that [the accusation] hurt my feelings.”

Talking to Zellweger, you’d think she has a genuine beefbut could she just be a skillful actress turning in a believable performance? Austin actor Robbie Jacks, who plays Leatherface in the Chainsaw sequel and can only be described as a disgruntled former friend, thinks so. He told me he’s sure Zellweger is lying, comparing her with scheming diva Eve Harrington of All About Eve. By contrast, Lisa Newmyer, Chainsaw’s other female lead, insists that Zellwegerwho happens to be her best friendis telling the truth. For her part, Zellweger argues that there’s no way an actress of her limited clout could make a movie studio put a finished film in mothballs. Perhaps, but Columbia/TriStar paid only $1.5 million for the distribution rights, an amount of money that gets written off on an average Tuesday in Hollywood. In any case, Chainsaw’s producers had to go so far as to file suit against the studio, and late last month, finally, the film opened in select cities.

Zellweger says she was “grateful for the experience” of appearing in Chainsaw, and even if nobody saw it, it helped her develop an early body of work she describes as “Generation X whatever.” Her next film, Love and a .45, surely fits into that category, though Zellweger’s performance as the female half of your standard twentysomething Bonnie and Clyde knockoffs earned her an Independent Spirit Award nomination along with the close attention of agents and studios. On December 4, 1993, she got into her red Honda Accord (outfitted with a CB radio installed by her dad in case of an emergency) and headed for Los Angeles. She spent the next eighteen months busing tables at various restaurants to make ends meet, but she also acted in two films: Shake Rattle and Rock, an original Showtime production that was part of the same B-movie series as Texas-bred director Robert Rodriguez’s Road Racers, and the forgettable Empire Records, an alternative-rock soundtrack disguised as a full-length feature.

The Whole Wide World was where Zellweger left “Generation X whatever” behind for good. The true story of West Texas schoolteacher Novalyne Price and her unconsummated love affair with Conan the Barbarian creator Robert E. Howard came along at a time when Zellweger wasn’t eager to do much of anything, because of the June 1995 suicide of her former boyfriend Sims Ellison, the lead vocalist in the Austin heavy-metal band Pariah. Ironically, Howard also had taken his own life, in 1936, but even if he hadn’t, the script still would have resonated. “I love that story,” Zellweger says. “It was the kind of film that moves me. And a story about a woman who has this incredible friendship and love with this man who is her inspiration, and then she loses him … I could not believe the parallels. I kind of had to do it.” The movie brought her back to Austin to face the memories; the house that stood for Howard’s was where The Return of the Texas Chainsaw Massacre was shot. Zellweger only got the part because the filmmakers’ original choice, Olivia D’Abo, would have been six months pregnant when the mostly outdoor summer production schedule began, but it’s hard to imagine anyone else in it. “We needed someone who could steal scenes,” director Dan Ireland says. Not an easy task opposite a showy, brooding performance by Vincent D’Onofrio as Howard, but steal scenes she did. The Wall Street Journal’s Joe Morgenstern praised Zellweger’s “quiet triumph,” calling it “direct, urgent, sweetly sensual, big and modest at the same time, and unerringly witty.”

Zellweger had just arrived at Sundance in 1996 for the debut of The Whole Wide World when the phone call came: She had won the role in Jerry Maguire. The obligatory Variety gushand the less-obligatory New York Times miniprofilefollowed a few days later. As the story goes, Zellweger had hit it off with director Cameron Crowe, who, as a former rock critic, was able to bond with her over Austin music. A series of callbacks followed. “It was funny because you park on the far side of the Columbia lot, and you have to walk forever,” Zellweger remembers. “I made a lot of friends on my walk. By the fourth time, when I was there to meet with Tom Cruise, the maintenance guys were like, Go get ‘em! Good luck, Rene!’” Her rapport with Cruise was instant. Even in early 1996, before she had really worked with him, she told me that he was “wonderful and warm and giving.”

There’s a credibility to Zellweger’s performance in Jerry Maguire that stems in part from her anonymity: She brings no baggage to the role, no habitual persona, no sense that she’s good at only one thing. The trick, of course, is to keep that quality after audiences get to know you a little better. “When the mystery is gone from a person, you can’t really believe them in lots of different roles,” Zellweger acknowledges. “They can only be who they are. I don’t want to be all over the place.”

So far she isn’t. The guy recognizing her at Authentic Cafe was an exception. Most of the time, when strangers run up to her on the street, they still yell “Jewel!” But those days are about to come to an end.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Renee Zellweger

- Katy